Firelei Báez: The Poetics of Opacity

Firelei Báez, On rest and resistance, Because we love you (to all those stolen from among us), 2020, oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 78 x 60 5/8 inches [photo: Phoebe d’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

Share:

I first encountered Firelei Báez’s work in 2011. We were in a group show titled The African Continuum, at the United Nations Gallery in New York. She was exhibiting Can I Pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of June (2011), and Cibyl (2011). Both of these works use the silhouette, an integral component of her work. Can I Pass? … comprises 31 self-portraits, silhouettes referencing race and the inherited colonial hierarchy of complexion and hair texture in the Caribbean and American South. Cibyl depicts a feathered, silhouetted figure. But the silhouette is not a simple mask; rather, it is what Martinique philosopher Édouard Glissant calls the right to opacity, a negation of the Western rubric of comparison—an invitation to the poetics of relations.

Over the years Firelei and I would cross paths, sending greetings and cheering each other on from a distance. This conversation marks the first time that we have been able to sit and talk as fellow Caribbean artists.

Cosmo Whyte: I want us to return to Glissant and talk about opacity. In your work you use strategies such as engaging cultural multiplicity, diasporic imagery of resistance and power, and subaltern histories. There are layers that camouflage the figures in your drawings and paintings, negating any transparent readings. How do you think about opacity and ambiguity in your work?

Firelei Báez: I think of opacity as, not necessarily armor, but as an assurance of a fuller self—that you can traverse the world without having to constantly pick up your entrails. Especially as a migrant, traversing spaces where you might not be fully seen as a member of that space—where you have to constantly self-validate—it’s like a constant gatekeeping happens. Traversing the world through opacity is this idea of meriting worth, irrespective of any doorway. You don’t have to put on airs, or you don’t have to take off airs, to be seen or to be appreciated. So it’s like a guarantee of appreciation, irrespective of the space.

CW: Yeah.

FB: Part of that has already been enmeshed in so much of contemporary art thought, especially if you think of Deleuze and Guattari. They incorporated Glissant’s theory so intrinsically into their thinking that it’s unquestioned. But the generosity of the original intent is still not enacted.

Have you heard of The Nap Ministry? Tricia Hersey, the founder, is articulating and theorizing the need for rest as resistance, especially within the Black and Brown community. This idea of rest as resistance is an arsenal that has been passed down from our ancestors. There are different platforms that are now trying to capitalize on that notion, making a very commercial use of it for White audiences, when it was meant to be specifically for and by Black and Brown creators and audiences. She’s been speaking out about that.

Glissant developed his theories for specific communities, and they were meant to help those communities traverse other spaces better. To then exclude the exact audiences whom those theories were originally intended for is kind of, you know, evidence that we still have work to do. It’s a fertile field, if anything, or a fraught field for reckoning.

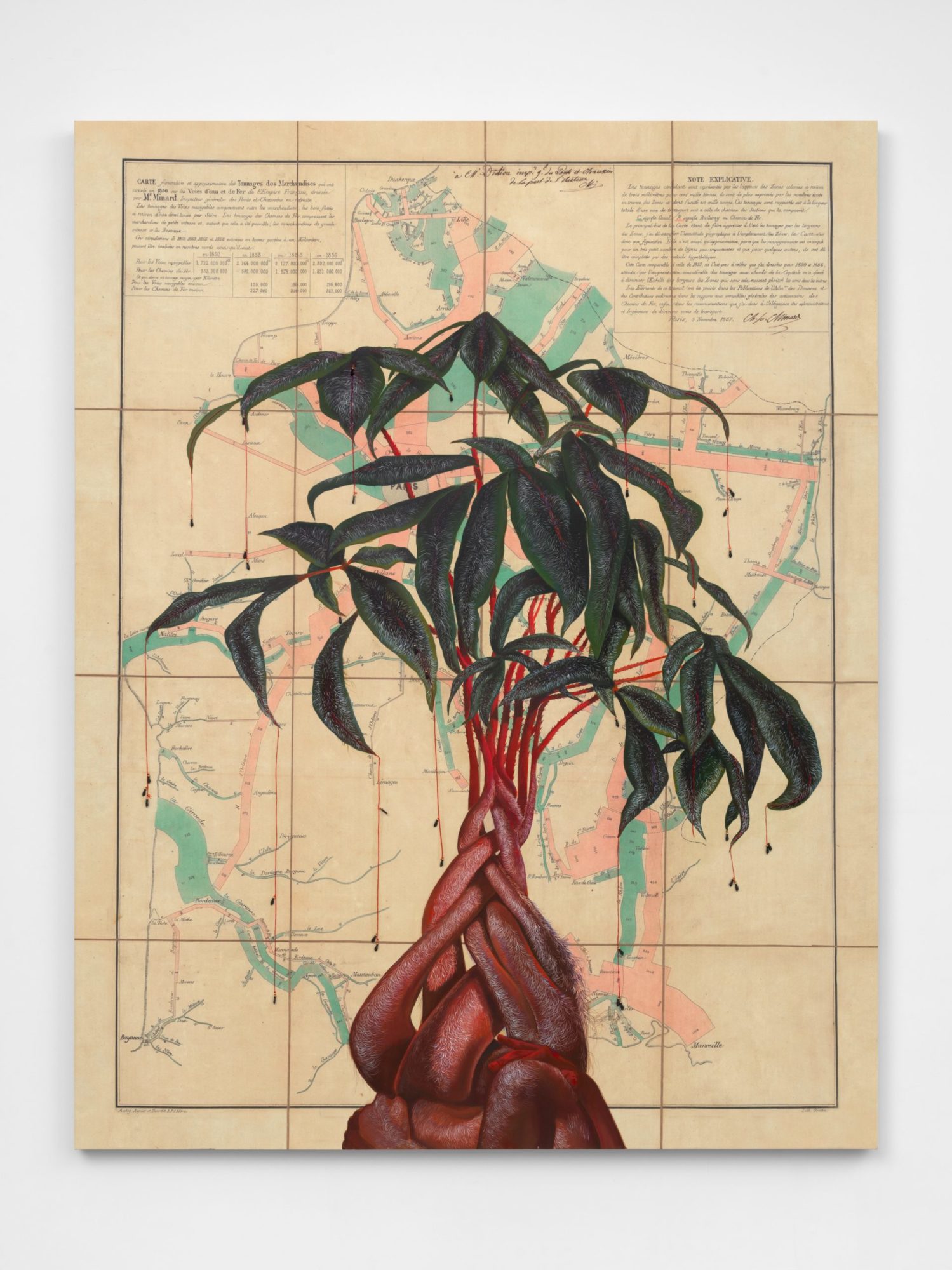

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Flow of merchandise in France on railways and waterways in the year 1856), 2020, oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 78 x 60 5/8 inches [photo: Phoebe d’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

CW: That actually segues nicely into my next question. You describe your practice as using materials that look from the Caribbean outward, placing them in a global context. This resonates so much with me as a fellow Caribbean artist. The work takes on a life of its own once it enters the world, which is inevitable. What has surprised you most about how differently legible the work is in the Caribbean versus other parts of the world, whether that’s the US, South America, Africa, or Europe?

FB: In some ways it’s been really joyful and rewarding to see things resonate. In the Netherlands or Utah, for example, some parts of the work that have resonated relate to the female body and women’s work—that’s both physical and emotional, the labor of traversing the world as a woman. Those things usually get picked up and expanded. I try to get to the specificity of the generosity that’s enmeshed in Black resistance—the way in which liberation has never been solely insular. It’s always been expansive.

But I’ve gotten some responses of defensiveness. When I cite the Haitian Revolution’s pivotal role in modern world history, for instance, I try to bring both the sting and the honey when I deliver information. Depending on who’s listening, they might pick up one or the other, instead of the combination of both.

Our ancestors deployed an arsenal of subversive strategies to preserve their humanity in its full emotional nuance, sometimes outside of Western-predicated ideas of propriety. Many of which remain as part of our present daily practice.

Sometimes people will approach me to verify the sexual or moral propriety of the histories I depict. “But were they married?” they’ll ask about the people they likely know were legally barred from marriage or even legal filial kinship. Who were often punished or mutilated for trying to do so.

Imagine not being able to hold and protect your partner or child. Many newborns in the black diaspora throughout the Caribbean and Latin America and Brazil wear a pendant, a symbol of resistance and healing, known as either an azabache or figa. In some histories passed down in Brazil, this hand gesture of a balled fist with the thumb between the index and middle finger was used as a subversive code by enslaved people to express their desire to be intimate, outside of the inhumane breeding system enacted through chattel slavery̨̨. Today this gesture for many of us is a protective symbol, to ward off evil. In Europe it is now mostly understood as an obscene gesture.

So the blocks are always discouraging, but when people are actually able to empathize, rejoice, and revel in that nuance, it is always beautiful. It’s tricky.

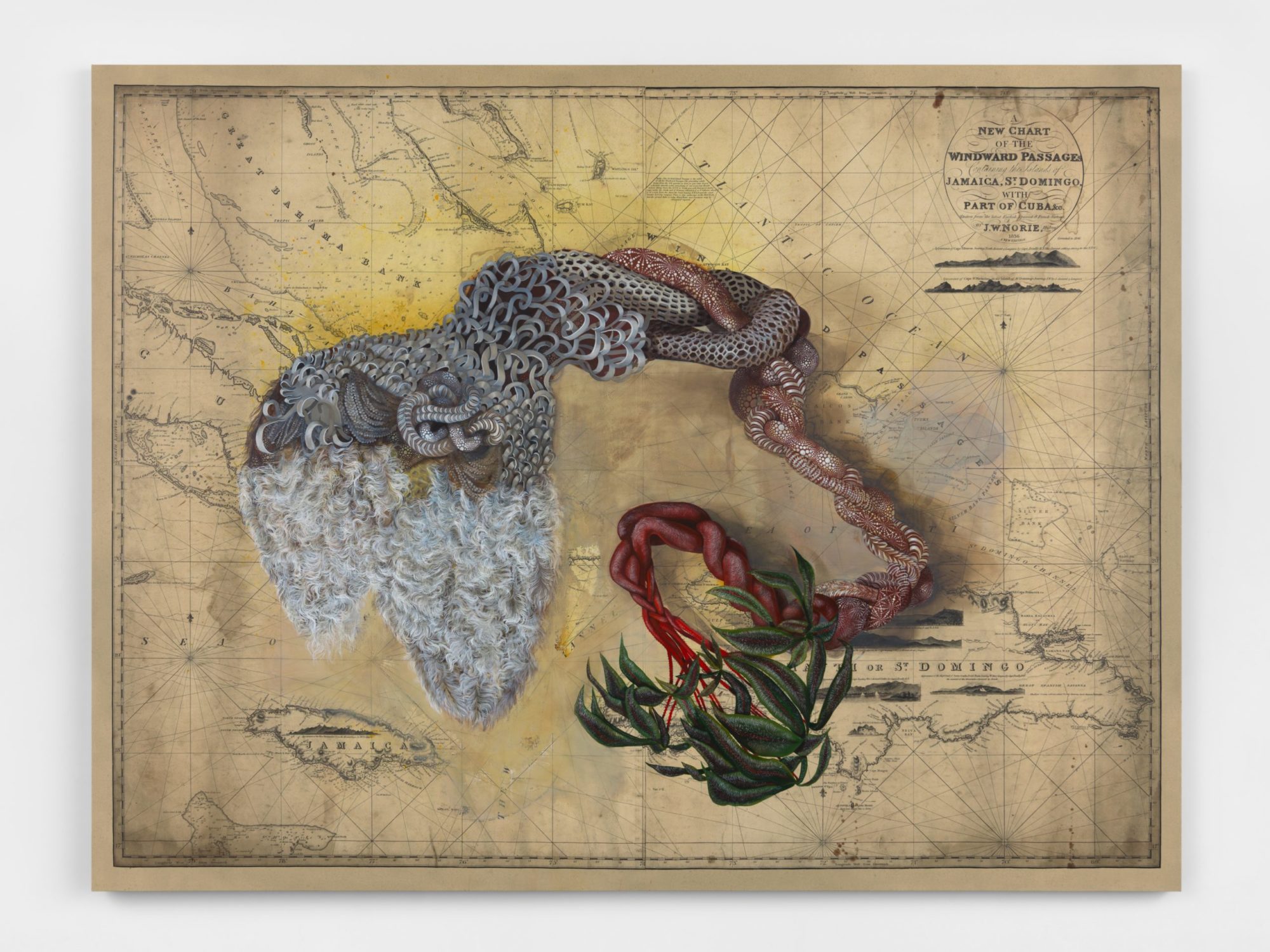

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Anacaona), 2020, oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 96 3/8 x 127 3/8 inches [photo: Phoebe d’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

CW: Yeah.

FB: What’s been your experience with that?

CW: I always am mindful that the work I’m making has to resonate—and this is solely for me to have an internal barometer, in some shape or form—within a Caribbean context. So I’m always asking myself, how is this going to read in Jamaica? And in doing so, there’s always something coded in the work that is going to get lost in translation. The frustrating part comes when there’s a push to overexplain everything. It almost feels like a push to have everything assessed and validated according to the idea or metric that I’m trying to push against. I’m trying to reorient the Caribbean as my central point of perspective.

FB: There are other artists from the Global South that are successfully very hyperspecific to their personal space, their familial histories. Like Njideka [Akunyili Crosby]. She revels in her family and the particularities of her life growing up. I think certain codes translate. There are ideas of class, and ideas of marriage or relationships that seem to have a direct clear language across any space. But she never really makes it a thing to just be, like, “A means this, B means this.” I tend to work hypersymbolically—I know what every single element means for me. When speaking of the work I almost have to stop myself from revealing it all. I have to remind myself of Glissant, to be, like, okay, you don’t need to ….

CW: Right. That’s why I wanted to start off this conversation talking about Glissant. I always had that inclination when I looked at your work, but to hear you evoke him specifically, I just was, like, ah, okay, this is my entry point. Because it’s something I have grappled with as well.

FB: I thank Elia Alba. She’s the one who introduced me to his work. I used to—and I still do—work in many, many layers. So every painting ends up being a palimpsest, with paintings erased and restarted in one work. And she said, “You might be interested in this philosopher. He’s done great work, [laughs] and in your works, there seems to be some synchronicity.”

CW: I want to talk specifically about the work that features the ciguapas. Can you explain what the ciguapas are? I’m also interested in integration of archival imagery, particularly the maps in these paintings. Can you talk about the significance of these elements and how they add to your [work’s] occupying a space of multiplicity?

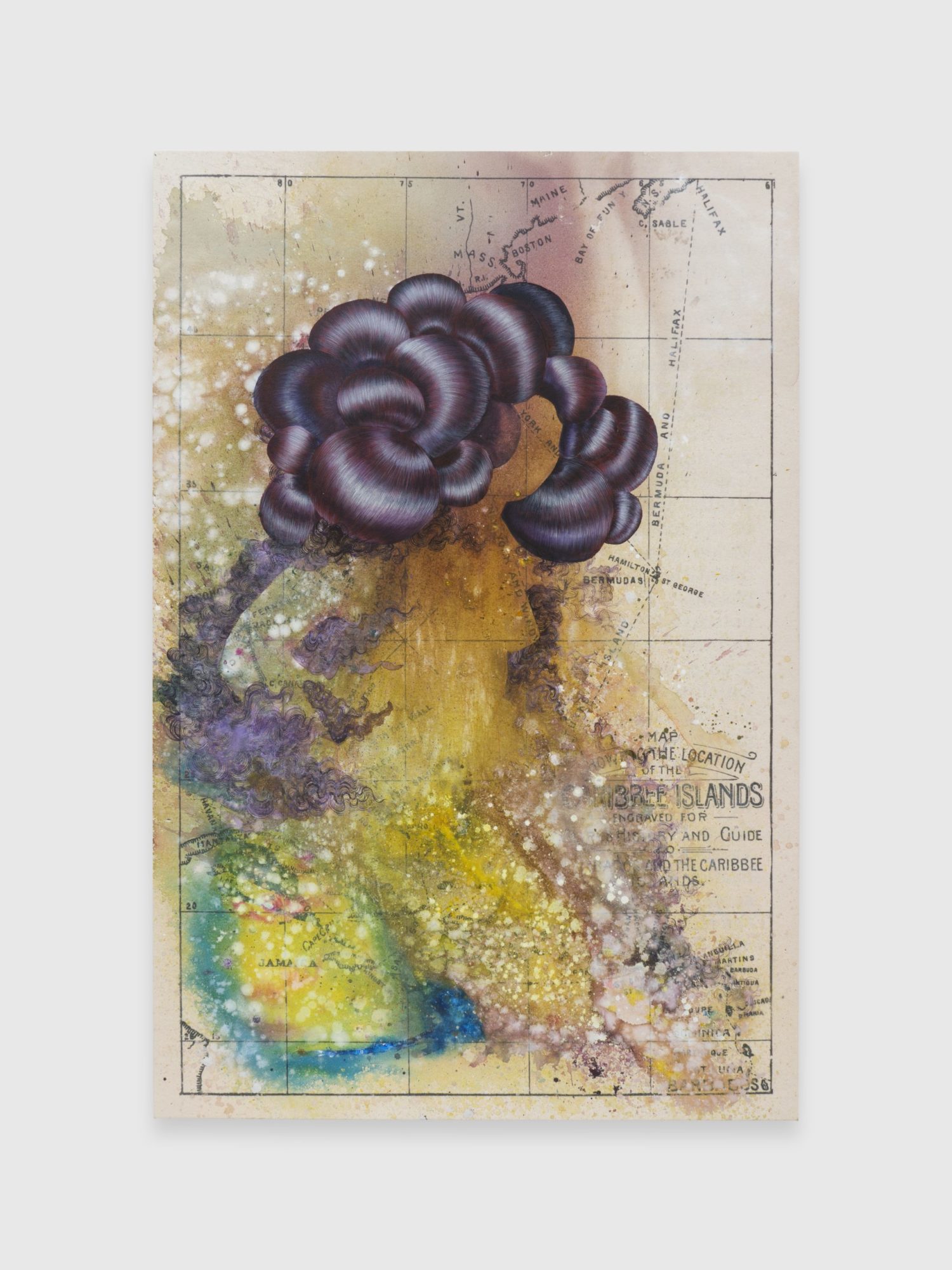

Firelei Báez, Chrono-DREAMer, 2019, oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 72 x 48 inches [photo: Phoebe d’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

FB: Hm. You’d think after working on this series for 15 years I’d have this quick elevator pitch for it, but it just keeps evolving.

The origin, for me, was hearing about ciguapas as a child and having these stories be told to me as a warning. Ciguapas are female trickster creatures from Dominican folklore. Their bodies are covered with fur, and they have backwards legs. Growing up, we were warned not to be like them, because they are thought to be too wild, too fearless, too unruly. They did not follow the rules and were not to be trusted. The best way to get kids really interested in something is to say it’s not allowed, that it’s off-limits. So the forbiddenness was really enticing to me as a child, and this idea of liminal space that shouldn’t have been accessible to me. The undertone of the story is that, if you’re brave enough, you can live within this open space the being occupies.

As an adult, and especially in grad school, there were these methodologies for looking at the environment in relation to the body, and [for] studying language and the psychology of space, that the ciguapa figure lent itself to. Layering all that nuanced information into one being—into one thing—allowed for a multivalence, an embodying from within, that denied the scrutinizing gaze and sabotaged the very constructs which often denied access to people like myself and the places I come from. And offered, in turn, conceptual and visual strategies of resistance. For me, the figure then became both a Rorschach and a palimpsest. Viewers could project their inner selves onto the figure in ways that I felt were more generative than me saying, “In the Caribbean, landscape is this.” Granularly asking: What is your relationship to language? What is your relationship to the body, to the environment, to architecture? More directly, from myself asking the viewer, in a global context, to question their constructs and consumption of the Caribbean.

The ciguapa also contradicts the way language in the Caribbean is gendered, especially in Romance languages. In the anglophone, Ibero, and francophone Caribbean, there are so many overlapping traditions, but language and religion have created these granular differences that are just fascinating. In the Dominican Republic and Haiti, both Romance-language–speaking spaces, there’s this gendering of language. The feminine is passive. It’s meant to be receptive. With the ciguapa, you have a combination of the passive landscape and the active female. These things that are meant to be antonyms merge and become something new. Passive and active energies, to be held in equilibrium by every living being. So with the ciguapa it’s just this idea that we are constantly changing. It’s really beautiful and valuable to give ourselves the space for being both gentle and fierce as we live our lives.

To answer the other part of your question, the maps and blueprints in my work usually come from materials de-accessioned from different libraries. I’m fascinated by the process of de-accessioning and what it reveals not just about information being thrown away, but about what the institution wants to be seen as. Many of my larger-scale paintings come from diagrams of sites in New Orleans. They are WPA-commissioned blueprints of important architectural sites. In many ways New Orleans is the northernmost extension of the Caribbean.

CW: Right.

FB: The Louisiana purchase was predicated by the Haitian Revolution. At least two thirds of the current-day United States, at the very minimum, is wholly indebted to that, and without it would be primarily speaking either Spanish or French today.

I’m fascinated by this [possibility], and [by] the idea of having the figure of the ciguapa traverse this fraught landscape, hopefully acting as a catalyst for change within it. What do we charge when we enter a space, or when we evoke a space?

CW: This is a bit of a tangent, but I recently, finally, got around to reading Edwidge Danticat’s The Farming of Bones, and as I was reading it, I thought a lot about your work.

Are your new works a continuation of the explorations you’ve been on, or are they a departure?

FB: For me, all the work is a continuation, an unfolding of a core praxis. And then I’ll do a painting, and people will be, like, “Huh, where did that come from?” I give myself room to have a broader visual language, which sometimes makes it hard for people to easily trace. For instance, I did this explosive feather painting for Artes Mundi, which I read in the visual tradition of masks. It’s this 10-foot painting that emerged out of a lot of physical, energetic brush work. It’s abstract and it’s figurative all at once, and there’s so much that could be projected onto it. But for me the main idea was all the adaptive languages, the acrobatic efforts that we have to adapt to navigate. Especially thinking of Mardi Gras and how that is short-coded language for— [knowing look]

CW: Yes, oh my gosh. [knowing laughter]

FB: Right?

CW: Yes, I know exactly what you’re talking about. That has also been my fascination with Carnival, particularly Carnival in its diasporic settings, outside of the context of the Caribbean. It’s this emancipation, but also the contortions are reminiscent of navigating the many moving parts of race in America.

FB: Yeah, and we always talk about the joy of it, how we always have to make room for that joy. There’s all these sacrifices you’re making at one end, but you’re in the same space, carving out room for selfhood and joy, by any means, you know?

I think I’ve said these same things to other people, just those words, and they’re, like, “Huh, language, okay.”

I’m, like, “Speak to a Caribbean!” [laughs]

CW: [laughs] Yeah.

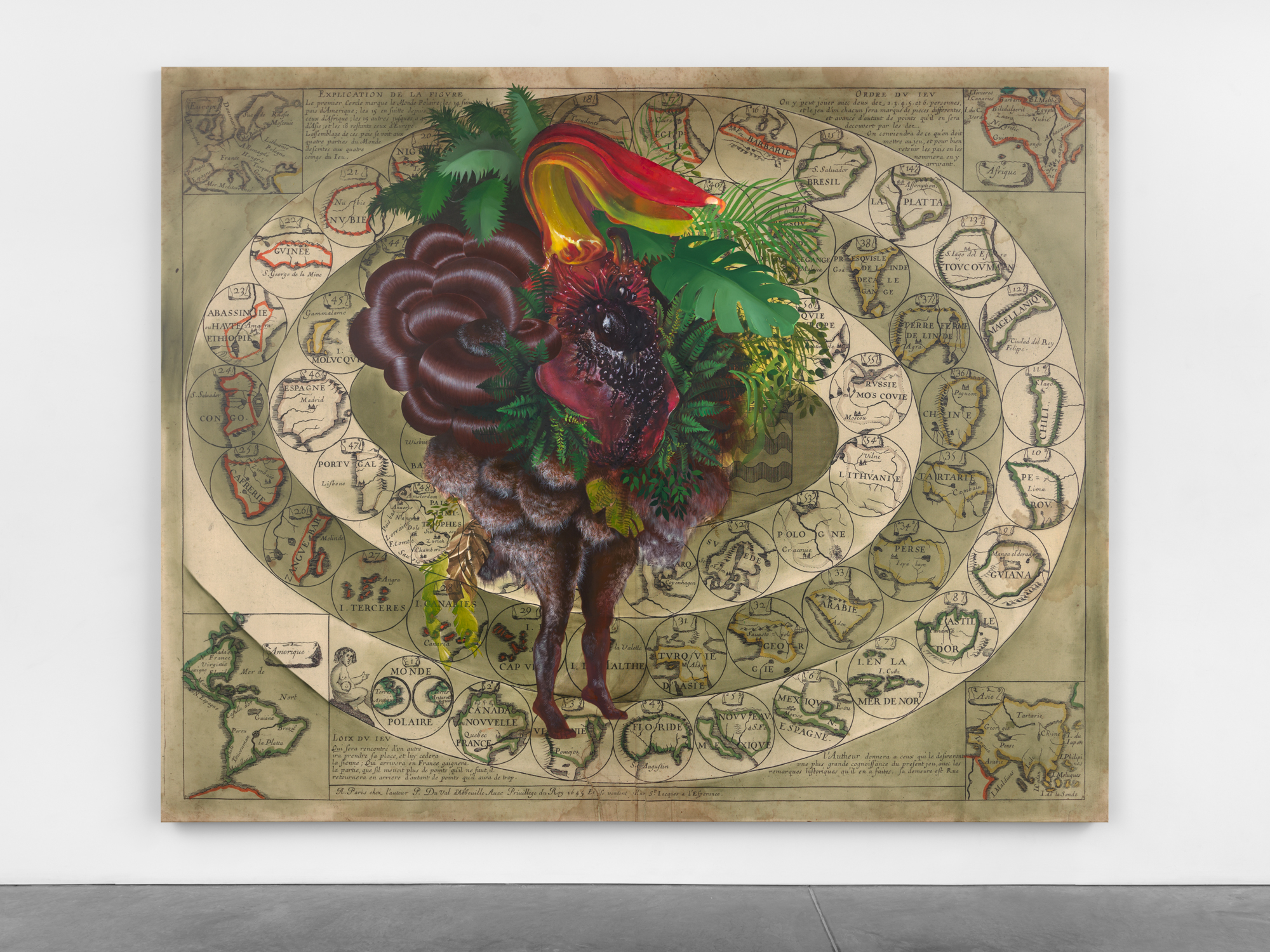

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Le Jeu du Monde), 2020, oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 105 x 131 ¾ x 1 5/8 inches [photo: Phoebe d’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York]

FB: The nuanced cues—I mean, if you talk to just anyone about the language of the steel drum—how, in itself, you could speak. You could have complete ideas expressed. Someone could hear it and just hear joyful noise, hear sound, but it’s a sophisticated, developed language that has multivalence. When you can fully appreciate that, you can go all the way to the moon! Ah, sorry, I get so excited.

You know, now there is this technology that can re-create a space just from an echo, of a potato chip bag, for instance. There’s all these magnificent technologies that can traverse time and space. For instance, with this echo-technology, you can not just see the space that the thing occupies now, but what it occupied before. So in theory you could scan an amphora from the fifth century BC and see the studio it was made in. We have that potential.

But to think of the steel drum and the technology, the language technology, involved in making it, in theorizing and ideating this thing—what if we had an expansive way of not putting all these doors up to seeing each other as humans? We could share all these ideas and have the potential for progress. It would be incredible. And not progress in the capitalistic model of avarice and consumption. Not knowledge as this assimilating, erasing thing—but as something that constantly crystalizes and becomes new. Like the growing of cells in trees. They can both grow and share ideas with other trees as they move along.

CW: I don’t have any other questions.

FB: What are you working on?

CW: So, I’m working on a series of drawings from archival imagery of Black resistance and protest, and a series of hand-painted, beaded curtains.

FB: I saw. It looks fucking amazing.

CW: Thank you, thank you.

FB: I know I’m not as informed with, I know, the big revolutionary movements and Steve McQueen—I saw Small Axe.

CW: I know, I haven’t seen it yet. I’ve been putting it off.

FB: I love it.

CW: I know I’m going to love it, I just—

FB: Why are you resisting it?

CW: No, I’m not resisting. It’s just carving out the time to sit down, and I haven’t.

FB: I literally put it on while I was painting, and just hear, like, the music and dialogue. And then you see the visuals, and it’s a whole other thing. So I’m just saying. It’s very particular compositions in each one. You can enjoy it as sound, and as visual, and as both.

CW: Yeah, and it’s my understanding that part of it covers the Brixton Riots, which is something I’m particularly interested in.

FB: Yeah, it goes into resistance movements from the 60s to the 80s, so it’s just a dance party of resistance.

Cosmo Whyte was born in Jamaica and has exhibited his works there, as well as in the United States, The Netherlands, Norway, England, France, and South Africa. Whyte has been the recipient of the Harpo Award (2021), a fellowship from Art Matters (2019) and Biennial Competition Award from the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation (2019), the MOCA GA Working Artist Project Award (2018), The Drawing Center’s Open Sessions fellowship (2018), Artadia Award (2016), the International Sculpture Center’s Outstanding Student Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award (2015), and the Forward Arts Foundation Emerging Artist Award (2010). Whyte attended Bennington College in Vermont for his BFA, Maryland Institute College of Art for a Postbaccalaureate Certificate, and the University of Michigan for his MFA.