Fall Exhibitions at SCAD Museum of Art

Share:

SCAD Museum of Art’s fall exhibitions engage ideas of sensory activation, retrospection, glitches, material, and myth. Each exhibition stands alone, carrying its own conceptual integrity, but their proximity and simultaneity bind them together. The exhibitions refer to a time-intensive art practice—examining the passage of time, symbolizing it through material, or toying with it to tell new stories.

The museum’s alumni-spotlight gallery holds Anya Molyviatis’ exhibition, SUBMERGE. Hanging on the walls and the ceiling is a series of 7-foot-long weavings that feature bleeding colors. A meticulous weaver, who spent a month on the loom making each work, Molyviatis aims to awaken the senses and create novel relationships between colors inspired by nature. In a continuous loop of warp and weft, cotton runs vertically, and mohair wool runs horizontally, creating gradients and a 3-D element. Using a dobby loom—one of 20 in existence—that allows the warp threads to be raised and lowered, she creates small craters that lend resemblance to a honeycomb.

Anya Molyviatis, SUBMERGE, installation view, 2024 [courtesy of the artist and SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah]

Anya Molyviatis, SUBMERGE, installation detail, 2024 [courtesy of the artist and SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah]

For Molyviatis, weaving such colorful fibers captures motion. Her work forms visual vibrations that tickle the mind in the manner of a Rorschach test and reminds us that we can receive moods, signals, and mental stimulation from color. The 3-D aspect of the work, for me, evokes the gills on fish, and technically, when finished, the weavings breathe on their own, taking on a different life when hung in the style of “2-D” artworks.

SCAD Museum of Art’s main galleries unfold in a mostly linear order, such that visitors pass through each exhibition to reach the next. In the first galleries, George Clinton (the prime minister of funk) presents Cloaked in a Cloud, Disguised in the Sky. Few people think of Clinton as a visual artist. This exhibition blends his visual artworks with visual elements from his work as a musician, which serves as an introduction to his visual-arts inclinations and as a reminiscence about how art has decorated his career. Sketches, drawings, and paintings line the walls, alongside a selection of his iconic costumes on display. His paintings rely on symbols and figures; in the larger works, you can see the layers of different mediums such as spray paint and acrylic. A repeated subject is the dog—the Atomic Dog, if you will. Clinton considers the dog an outgrowth of that song, one of his signature themes, and it grew into a mascot akin to Mickey Mouse for Walt Disney—except Clinton’s dog says, “Bow-wow-wow-yippie-yo-yippie-yea!”

I was shocked to learn that Clinton has achromatopsia—total color blindness. Thinking of his iconic photoshoots, Parliament album covers, and his entire career of visual funk, I couldn’t believe he saw only in black, gray, and white. It is magical to wield color in the way he has and not see any of it. I set my camera on the black-and-white filter and looked at every work as if through his eyes. He paints in contrast, tones, and shadows. He uses negative space to avoid overcomplicating his compositions, which causes his subject matter to float, as if emerging from an ether. For Clinton, a painting doesn’t start with an idea of desired hue. Instead, he reads the color on the paint jar and goes for it. Just another lesson from Dr. Funkenstein: Never let anything stop the funk!

George Clinton, Cloaked in a Cloud, Disguised in the Sky, Installation view, 2024 [courtesy of the artist and SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah]

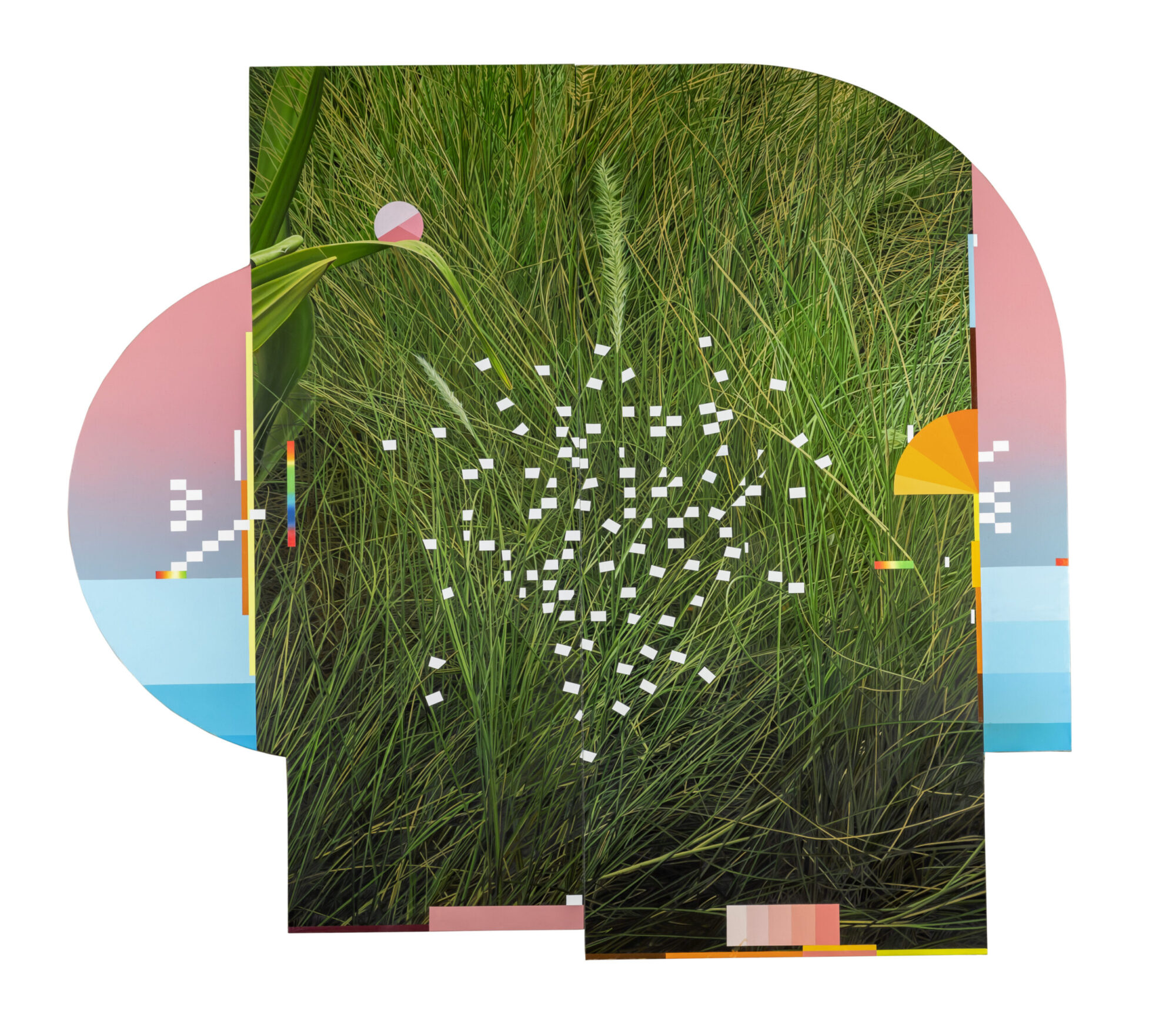

The next galleries feature Arboretum by Thukral and Tagra, a duo who create photorealistic paintings. They reject the typical rectangle and instead offer organically shaped canvases tiled together in puzzle piece formats. Each painting depicts an arbor, but little devices distort the image; the artists call them memory boxes, mirror boxes, and reflectors. The repetitive elements demonstrate Thukral and Tagra’s technique of producing fractals—each box differs from the others because it charts the painted trees’ changes through the glitch of passing time. Their work allows access to a fleeting second during a moment of change, when the glitch is recorded. The subject of the arbor alludes to time and the ephemeral qualities of nature while calling attention to trees as cultural artifacts that witness the social and political transitions of the world.

In the middle of the exhibition is an iceberg-shaped structure with miniature canvases placed on all sides. The structure represents the hidden network between trees as they pass nitrogen and carbon through their roots. The artists refer here to the “wood wide web,” a term coined by scientist and professor Suzanne Simard. The work calls for people to pause and consider their own arboretum closely, as well as reminding us how much can be missed if we don’t pay attention.

Thukral and Tagra, Arboretum 10-Carex Flagellifera, 2022, oil on canvas with artist-made wooden stretcher, 77.5 x 86.5 inches [courtesy of the artists and Nature Morte, India]

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola’s Good Hair is presented in a narrow, hallway-like gallery. The exhibition includes Sunday’s Best (2024), a 48-foot-long composition of silk durags, stitched together in a color block pattern. Parallel to it is The Price of Oil (2024), an installation that consists of shelves presenting a thoughtful assortment of ready-made hair products, and Spinnin’ (2024), consisting of two operating barber shop poles.

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola, Sunday’s Best, 2024, durags [photo: SCAD; courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles, and Night Gallery, Los Angeles.]

Akinbola works with durags for their material and conceptual qualities. By creating compositions whose colors come only from the durag’s fabric, he questions the material confines of painting and has formed his own language of pattern and texture. Placing color as a painter would, he builds a sea of varied hues, leaning on his memory of traditional Nigerian garb from his Sundays at church. In previous works, he explored monochromatic compositions and stitched the durags loosely, with their ties hanging down freely, for their heaviness and sway. But the monumental work exhibited here is taut, conveying stored energy, similar to when a durag is worn.

Opposite the bowling-lane-length durag painting stands The Price of Oil—installed steel retail shelves with grease and pomades arranged to mirror the color blocking in Sunday’s Best. What caught my eye first were jars of Blue Magic in neat rows. I felt as though the only way to truly encounter Blue Magic is if you smell it or see someone dig their fingers into it. In an interview with the artist, Akinbola told me that’s how I’m supposed to feel, almost like, “if you know, you know.” However, in case you missed it, this work is not depicting the Black hair care section at your Ulta or your grocery store. Instead, it represents a moment of visibility within commercialization. These greases and pomades understand the spectrum of textured hair and have offered quality hair care for generations.

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola, Good Hair, installation view, 2024 [courtesy of the artist and SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah]

Spinnin’, glowing red, white, and blue, hangs at the end of the hallway. Today the revolving spiral is a signal to come in, take a seat, and chop it up. In history, it was to organize, congregate, and rally. But in both those contexts, it marks a safe haven. The display of these cultural tools reminded me that this work, at its core, is meant to make you feel something—whether that’s nostalgia, confusion, or interest; if everyone doesn’t get it immediately or needs to put words on it to make it digestible, so be it. The real power of the work lies in subverting the expectation of explanation. Good Hair reminds us of what the material world carries within it, and that it has the power to produce culture, over time.

In a dimly lit black box gallery is Monira Al Qadiri’s Holy Quarter. Viewers encounter an image of W.A.B.A.R (2024), a site-installation of large, round sculptures resting on the Oman desert floor in the Empty Quarter. For Al Qadiri, born in Senegal and reared in Kuwait, the desert is not an alien landscape; it’s her natural habitat. But sculpture is a risky concept for Arab artists—it can be seen as idolatrous. To Al Qadiri, sculpture is exotic, and she enjoys the taboo of it all.

The story behind the forms begins with a myth from the Bedouin tribes native to the Arabian Peninsula, who are known for passing down oral histories. A British explorer named Harry St. John Philby scoured the Empty Quarter amid hopes of finding the lost city of Ubar, which the Quran described as having been destroyed by God. Instead, he found craters, which he thought were volcanoes. In the rubble, he found meteorites, which he thought were pearls. Philby was then overcome with sadness because his colonial hubris failed him.

Monira Al Qadiri, Holy Quarter, installation view, 2024 [courtesy of the artist and SCAD, Savannnah]

Al Qadiri took that tale as the basis for this body of work. She created a film narrated from the perspective of the “pearls,” to examine them as characters in the myth and history. Her grandfather dove for pearls—the central Kuwaiti industry until oil was discovered and the world was tricked into following a new self-destruction plan. Al Qadiri found parallels between the value of pearls and that of oil, which infiltrated public consciousness due to guaranteed financial reward, allured the masses with their iridescence, and ultimately destroyed environments. Parts of the film show the wind causing ripples in the sand, evoking ocean waves and the intrinsic connection between environments. The film’s narrator is an AI-generated voice, granting sci-fi undertones and delivering historic lore over a chilling score composed by the artist’s sister, Fatima Al Qadiri. In front of the screen lay 46 black, blown-glass sculptures scattered and subtly illuminated, echoing the pearls’ sacred origin. Encountering these forms, I remembered Monira Al Qadiri explaining why she chose glass to represent the pearls. In the desert, nothing survives. You can’t make and keep objects, as the sand will erode almost everything. Because glass is a withstanding exception, it finds a home in the sand. The retelling of this fabled story produces a new myth as she sends the pearls back home to rest. After all, with one strike of lightning in the Empty Quarter, it could be true.

Samaira Wilson is an artist and writer. She received her BA in Studio Art and Global International Studies from Bard College. She regularly contributes to Elephant Magazine, and for stints at a time, is a resident at the Mildred Thompson Estate Residency, developing her art practice.