Amber Esseiva: Call and Response

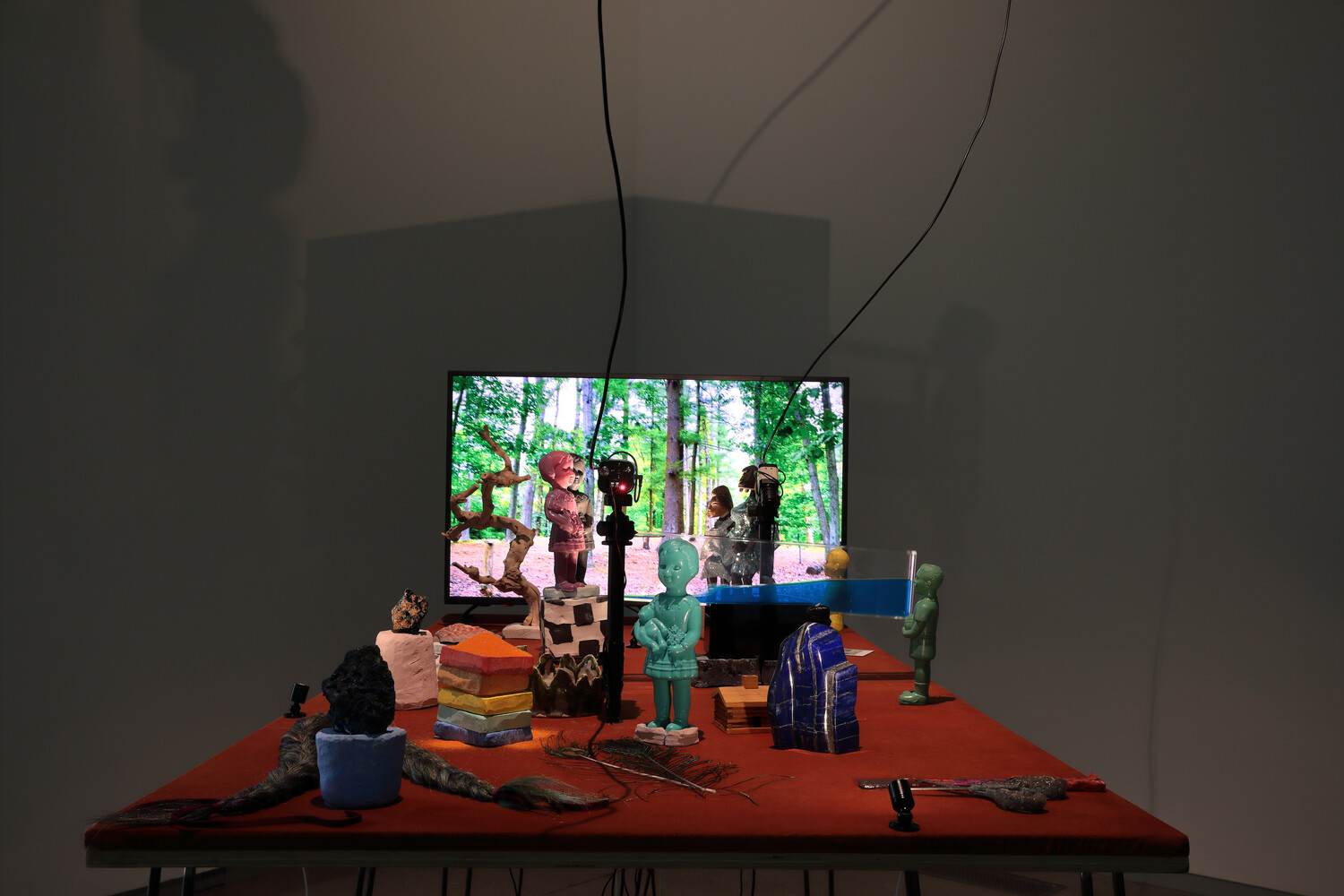

Cauleen Smith, I Need To Speak About Living Room (After June Jordan), 2024, installation view, installation view, at the Dear Mazie exhibition [photo: David Hale; courtesy of the artist and Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

Share:

Amber Esseiva is curator of the group exhibition Dear Mazie, at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. Esseiva called upon 8 participants (a combination of individual artists and collectives) to respond to Amaza Lee Meredith’s legacy to spotlight her identity as the first known Black queer woman architect. The exhibiting artists/groups are AD-WO (Emanuel Admassu and Jen Wood), The Black School (Joseph Cuillier and Shani Peters), Practise (James Goggin and Shan James), Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, Kapwani Kiwanga, Abigail Lucien, Tschabalala Self, and Cauleen Smith. Drawing upon Meredith’s 5,000-piece archive, which Esseiva scoured for years, the artists navigate themes of placemaking, education, sexuality, and gender. For the exhibition’s conceptual framework, Esseiva chose the form of a written letter and commissioned the artists to step out of their usual practices to make new works that address different parts of Meredith’s life. I met with Esseiva at the ICA Café for coffee and pastries on the morning of the opening.

Samaira Wilson: When it comes to your nearly four-years of research, thumbing through Amaza Lee Meredith’s archive, how did you pick your approach to bringing this exhibition to life?

Amber Esseiva: It was a long process. For the first couple of years, I had no idea what I was doing. I didn’t know what I would find. I didn’t go in with a goal or a lens in mind. So, I started looking and was, like, “Oh, I found this thing. Now I have a new idea.” Then I was like, “Oh, I have to start from the beginning to look for that.” And there was a lot of back and forth.

I went in thinking I would uncover the way she built a Black art school—and that was there. But what was really there was an incredible amount of correspondence and relationship building between her and students, family, loved ones, through these letters. The pictures of the blueprints are immediately digestible. But these letters are handwritten things, and you have to read through years of correspondence to really understand the breadth of them. So, it took a long time to land on this idea of the letter being the throughline in her archive, and my approach to the show. I kind of knew from the beginning that I wouldn’t exhibit a bunch of archival material. I wasn’t going to make an architecture show where there were models or blueprints in vitrines.

I knew that my approach would be more experimental and unorthodox when it came to dealing with architectural history and archives. And then, the how just kind of unfolded. It took a long time because I had to convince 11 people to include this woman’s history into their artwork—someone they never heard of before. That took a lot of relationship building, of being like, “Wait, trust me, I see it. I see, in your work, an ability to bridge what you do to this topic, and it could really work.” So, I mean, it’s still unfolding. I haven’t fully digested everything yet. It’s just gone up.

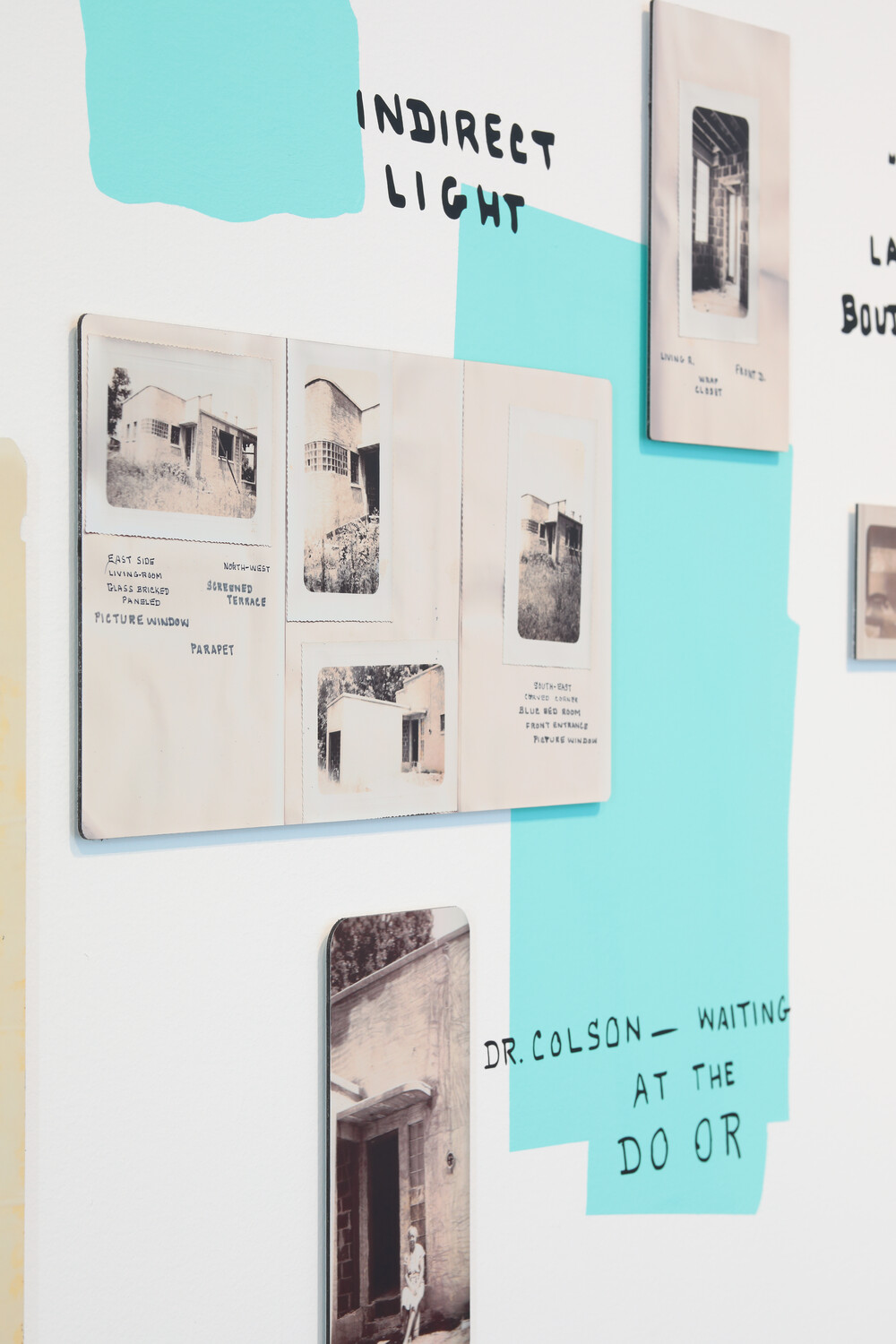

Dear Mazie, detail view of the archive wall, 2024 [photo: David Hale; courtesy of Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

Amaza Lee Meredith, date unknown [courtesy of the Amaza Lee Meredith Papers, Virginia State University, Special Collections and Archive]

SW: Right, and it takes on its own life once it’s up.

AE: Yeah. Then other people look at it and have different responses. So, it’s been a long process of going back and forth and testing things out. At first we were, like, “How do we build? How do we figure out?” And AD-WO—Jen and Emanuel—were my thought partners. Not since the beginning, but since the beginning of the exhibition production—the past two years—where I was, like, “Hey guys, I want [Meredith’s Azurest South home] to be in this show, but obviously we’re not bringing the house to this show, and we don’t have the type of money to build out a house in a museum that has all these fire codes.” And, it’s like, “That’s not possible structurally. So, what do we do?” They had a ton of different ideas. In the end, we landed on this massive curtain that functions as the façade of the house that wraps around the gallery.

I want people to feel like they’re walking into [her] house, but I was always, in the back of my mind, like, “Oh, the archival nerds are going to come for me,” because if I just do the contemporary art stuff, which is artists cherry-picking aspects of her life and running with it in their style, you don’t get her history. You get portions of it, not the full thing. So, it was the challenge of, “How do I tell her story—which is insanely intense, and has so many different strands—in a way that’s digestible as part of an exhibition design and that doesn’t turn this exhibition into a history museum?”

AD-WO and Practise were our book designers, but they came in early to help us convey this information. They built this 90-some-odd-piece archival timeline in the gallery, which you can walk across. You can see aspects of Meredith’s life from 1914 to the 1980s, and it’s completely separate from the art.

So, there were a lot of different forms that I was trying to fit together, and there are moments when it does that, and, I’m sure, moments when it doesn’t. The show is oscillating between truth and make-believe, where I’m just, like, “We’ve used her as inspiration, but we’ve run with something else.”

There’s ambiguity about what the truth is, in the show, and I think that’s just the nature of an archive. If I died today, and someone just started rummaging through my stuff and put it in an archive—you’re not going to get it all. Archives are just riddled with inaccuracies and half-truths. You may think something’s so important because she kept it in a drawer, but maybe she just forgot it there. Maybe it wasn’t that important to her—all these things we just don’t know, and we’ll never know. So, seeking the truth, in that regard, wasn’t something I was after. All I was after was that people need to know who this is, that she existed, that this house is here, and that Sag Harbor is where it is, and the Black community is there because of her. They’re just things that people don’t know.

But, I mean, there’s hype around her, because you find out, “Holy shit, this woman did so much amazing stuff. How does no one know about her?” I think that’s everyone’s first impulse. And then, what to do about that, what to do about the unknowable? So, the history of her is going to continue to be put through the lens of the speculative in ways that are interesting.

Dear Mazie, installation view, 2024 [photo: David Hale; courtesy of Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

SW: That’s why I think Dear Mazie, is beautiful, because the creative liberty you’re taking causes the 11 artists to produce new work, bringing Meredith’s legacy to the fore, and sparking new conversations between their practices and hers. How would you describe those conversations?

AE: This is why the epistolary—the letter form—was really interesting to me. A letter is very different from a conversation, or a text exchange, or an email exchange where there’s a back and forth. In a letter, you have to put it all out there and send it, and wait to see what the response is. Tschabalala, for instance, was really drawn to this image of Amaza and Edna Colson [her partner] in the archive, where Amaza just appeared kind of old, late in life, and close to death. Amaza is standing there and holding the handle of Edna’s wheelchair. Again, old and frail, but beautiful in their own way. And Tschaba’ was, like, “Okay, well, I’m going to make this huge, busty, full-figured, very young, very robust, alive Black woman,” in her fashion.

You would’ve never caught Amaza Lee Meredith with cleavage out. That’s not what her queerness looked like in the 30s, but that’s what it looks like in this show. And that’s what queerness looks like now, in ways—taking the same tenets, this idea of being Black and queer and being an artist, but in the scope of today’s history, and today’s realities, which makes it a totally different thing. So, it’s like these works are letters. Artworks as letters, back to her, that she’ll never answer.

SW: And these artists make work that overlap with her life. Like AD-WO, who negotiate racial and spatial relationships with land; and then The Black School, which built a campus for art education in New Orleans, similar to what Amaza did at Virginia State University. And then, Tschaba, who uses the Black woman’s figure to defy the narrow space in which it is forced to exist. The connections between everyone’s work illuminates the lineage among them.

Tschabalala Self, Heroine inspired by Amaza Lee Meredith, 2024, installation view, at the Dear Mazie exhibition [photo: David Hale; courtesy of the artist and Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

AE: She was very invested in the future, and was, like, “I’m doing this for the future of Black art students, Black artists, and Black architects.” So, I would hope that she would be excited by the future responding back. Like, “Okay, now we’re here ….” And it’s not unheard of to have a Black dean in the schoolyards. We have one. But it was unheard of then, and this show exists in a time when that’s normal. So, yeah, it’s a weird time collapse thing happening.

SW: How has her practice of architecture, by way of sanctuary building—like with Azurest South and Azurest North—been honored in the show?

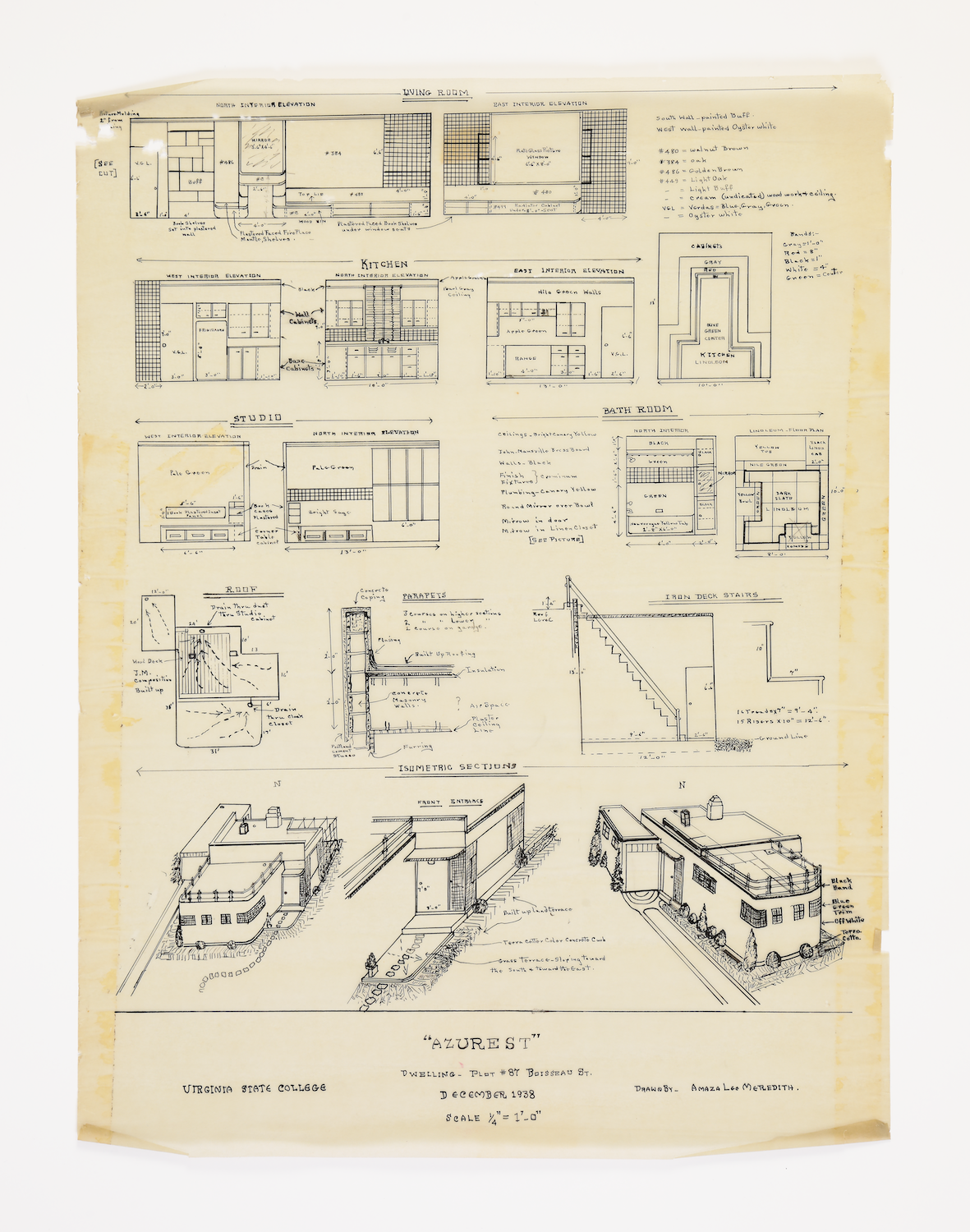

Amaza Lee Meredith, Azurest South Architectural drawing, 1938 [photo: David Hale; courtesy of the Amaza Lee Meredith Papers, Virginia State University, Special Collections and Archive]

AE: She becomes a lesson in a way to do activism. Activism, now, is seen through the lens of, “What does it mean to stand in the street and speak to power and defy in a way that uses protest?” But with Amaza, she was protesting, but she was also just trying to make some peace for herself. Her protest was, like, “I’m actually just going to build a house so the cops leave me alone, and it’s on a Black campus so they can’t come.” You know what I mean? “So that I’m protected, and my family can have some peace.” That’s what she was seeking.

Usually, protests are about disturbing the peace. And she was, like, “No, actually, I live in Jim Crow America. My protest is getting peace.” So, that’s what she did: “Let’s make a beach community. Let’s make a resort. Let’s make a house in a place that’s protected.” It’s a very different way of speaking to power, and that’s an important lesson—for me, at least.

SW: I think that within the Black community, in general and in history, community is wealth. Peace was hard to find and have. That’s something that white people have always had, and—

AE: They always try to disturb peace. Like, you’re walking in the street, trying to get a Coke, and it’s like, “Let me harass this person.”

SW: Yes, so, she sought to create a safe haven, a space where that didn’t have to be the constant stress.

AE: And that haven still exists today. Sag Harbor is filled with Black families that have been there for generations, and they’re going to continue to be there. She made a safe haven for generations of people.

SW: That’s really interesting, especially in this age of conversations surrounding Black utopia. Like, instead of it being a conceptual reality that’s far away, and that we have no contact with, she said, “Let’s make this real. Let’s actually make a place where we can have autonomy and recreation.”

AE: Yeah, and where people can own a home. A lot of people didn’t own homes, let alone beachfront property. It’s insane for the 40s. It’s still kind of insane now.

The Black School (Shani Peters and Joseph Cuillier), Roses for Black Builders, 2024, installation view, at the Dear Mazie exhibition [photo: David Hale; courtesy of the artist and Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

SW: How did you go about creating the atmosphere and the tone of the show?

AE: I think I wanted … what I always strive for—immersion—to feel like you’re in a diary or an internal world. One of my favorite pieces in the show is by Abigail Lucien. She made this little vanity with a letter, a steel letter, and a comb and a compact. A lot of Amaza’s correspondence to Edna, who was her lifelong partner, was pretty desperate. She was, like, “Please pay attention to me. Why are you ignoring me? I’m so in love with you. Be with me.” It was a lot of pleading, a lot of sulking. Most of her life, in the beginning, was filled with grief from her father’s committing suicide. Her father was White, and he just couldn’t deal with the harassment of having a Black family anymore. And so, she took that grief into an obsession with this lady—

SW: Her professor.

AE: —who pretty much ghosted her for years.

SW: Yeah?

AE: Yeah.

It’s like a harassment that’s kind of unethical because this lady was older and her teacher. So, Abigail made this sulking booth, this vanity where you could just imagine that she was writing these letters, begging. And that, to me, is way more interesting—that intimate strife we’ve re-created.

And she talks about—in her scrapbook—having a really special view outside her home, from a specific window, where she saw the woods on her property. So, we re-created that viewpoint, just a tiny thing that she would see when she was washing the dishes. But that, to me, was important. I would hope that comes out in the show, that it’s not a cold, top-down view of history. It’s a little bit weird and an overly intimate way of thinking about someone’s life. And it’s split up. When you walk in, you have an entry hall where it’s just facts. History is there. Then you walk into these weird, wishy-washy, speculative worlds. So, I’m hoping the feeling is that you’re both grounded in history, but also taken away from it in a way that feels immersive and sentimental.

Dear Mazie, installation view, 2024 [photo: David Hale; courtesy of Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

SW: That’s so difficult. You had to have spent those years in her archive to even fill in those blanks.

AE: And I’m projecting, of course. I’m, like, “Oh, I know what it feels like to do this.”

SW: But it’s your admiration of her and her work that makes you able to do that. I know you’re still piecing together how the show feels. But what do you want people to feel?

AE: I feel like I want … the thing I said about how activism can be disturbing the peace on the streets, but it doesn’t have to be disturbing your peace. It can actually be claiming it. And one thing that is a throughline in the show, and that you can’t get away from in her archive, is that she was a deeply community-based, loving, caring person.

Teachers don’t typically correspond with students for 50 years, write to them at war, and know their kids. This is just how she was in the world. She was a very genuine, personable person who truly cared about people, outside a profession, outside a career. Her care for people was the thing that drove her to education, and then drove her to her career. So, I would hope that the show is, like, “Oh, there are different ways to be in the world,” especially now, when people are so obsessed with themselves. Where it’s just, “Me, me, me,” Instagram, whatever. Instead, it’s, “Oh, actually interpersonal relationships are more important than yourself.” That’s what she cared about most. It was interpersonal relationships that drove everything she did, and I think that’s a good lesson in a time when there’s a lot of divisiveness.

Dear Mazie, installation view of the archive wall, 2024 [photo: David Hale; courtesy of Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

SW: Even though Virginia is known for being home to the capital of the Confederacy, this show is recentering a counterhistory. It’s like, “Actually, there are other things. That’s not the hallmark of this place.”

AE: Virginia can be known for Black modernism. That’s cool.

SW: Truly. That said, what does it mean for the ICA at VCU to open this exhibition, for the city and for its identity as an institution?

AE: I think we’re really lucky that we are able to tell the story. There’s never been a Virginia institution that has told the story of this Virginia monolith. So many history museums, so many places could have done this exhibition, but we got to do it, which plants it deeper in the time and space that is Virginia. We are not just doing weird, wacky contemporary art exhibitions that 5% of the population know how to read. We’re also doing things that represent our state and our country. We’re image makers as contemporary practitioners. So, I think that we kind of won the lottery, as far as being able to tell this story. And it’s doing exactly what we should be doing. It’s telling Virginia history, but it’s also telling contemporary art history.

SW: Yes. And you’re presenting her as a jack-of-all-trades who lived through her work, while putting her personal identity under a microscope in these imagined, intimate moments. Because, when do we get to see that? You know, when you see your grandma get ready or something? Like, “I shouldn’t be here, but I’m here, and I’m learning more about you, but you don’t know that I’m watching you.”

AE: Exactly. Yeah. We’re kind of voyeuristic, but in an admirable way.

Amaza Lee Meredith, Azurest North, date unknown [courtesy of the Amaza Lee Meredith Papers, Virginia State University, Special Collections and Archive]

SW: Yes. Carefully observing instead of trying to taint or take away or put words on it.

AE: Right, and I think that’s just a practice that people—because they live such fast phone lives—are just mimicking, and they’re not really observing a life. Just observing a very weird portion or advertisement of a life.

SW: I guess that’s why you say the show is romantic, because romantic relationships are one of the only times it’s just you and them, and you’re actually looking at them as a whole. And in romance you get to see them in ways they don’t see themselves.

AE: Yeah, it’s true. That’s really a good point.

SW: How did you approach her queer love story?

AE: I’ve always said that this show should have been chapters. It’s just too much information. I did my best, but there’s a lot in the show because I tried to do a lot. But really, in a perfect world, it should have been five different shows on different aspects of her life. The architecture, it should have been in chapters. And the love thing is …. From afar, everybody looks at them, like, “Oh, these were two power queers.” One of them, the art department is named after her. The other one, the education department is named after her.

They looked like a power couple from the outside. But the truth is, when you look at the archive and the letters, there was just constant pleading by Amaza to be with Edna. There was a lot of loneliness. And maybe that’s just the nature of having a romantic relationship via letters. You’re waiting for the fucking mail, and we’re used to such immediacy.

All the many queer people in the show, their queerness looks different, because today you can be totally yourself, for the most part, and you can chart out your identity. But Amaza was such a church girl. She went to a Baptist church in Petersburg, and everybody knew she was queer, but nobody talked about it. She wasn’t walking around, like, “I’m queer.” It was, like, “This is my friend Edna.” Everybody knew it, but it was an unspoken thing. It wasn’t out and proud. She was able to live a life where she fit into Jim Crow, racist, homophobic America, only to be remembered as a queer great. She wasn’t walking around acting like a queer great. She was quiet about it, very quiet. While we’re obsessed with branding our lives and branding our identities, she wasn’t putting that brand out there, but then she got recognized for that at the end.

Then, Amaza’s being so religious—despite there being so much homophobia in religion—she was just, like, “No, I’m actually a very spiritual person, and my spirituality is queer, and it’s in nature, and it looks like this.” It’s really cool. I think we’re living in a time when it’s necessary to rebuild the institutions around us, but it’s a time of rejection. Rejecting patriarchy, rejecting hierarchy, rejecting whatever. And she was just, like, “My identity in itself rejects that stuff, but I’m moving through it.” She seemed really good at being uncomfortable for a long time, which is crazy. We’re not used to that.

Cauleen Smith, I Need To Speak About Living Room (After June Jordan), 2024, installation view, installation view, at the Dear Mazie exhibition [photo: David Hale; courtesy of the artist and Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

SW: And Edna—they ended up living together?

AE: My husband doesn’t agree, but my theory is that Edna ghosted her for a really long time and was, like, “Well, I’m going to mess around with other students. I am going to do my thing,” until Amaza started being a property owner. And then she was like, “Oh ….”

SW: You’re serious.

AE: Like, “This is something I need. I want a beachfront house. I want a modernist house. I think I’ll end up with you.” So, I think the architecture is the thing that won Edna …. Again, this is me totally making shit up, but I think that’s what ended up sealing the deal.

SW: Wow. Wow. Wow. It’s so interesting that you said you’re playing make-believe. But I’m, like, how else are you supposed to interact with the archive, if not that way?

AE: Some people are very full of themselves. Like, “I’m telling a true history based on this timeline that’s accurate.” It’s not accurate. She wasn’t building an archive when she was living. That house happened to be on campus. So, if she had lived anywhere else, that stuff would’ve probably all been in the trash. But, because the house sat on a university campus, they didn’t know what to do with it. So, they’re like, “Let’s just put it all in boxes and call it an archive.”

I think people want to imbue themselves with a lot of virtuosities, so they further dig their heels into this idea that they’re telling the truth, or that they found a record of the truth, because that’s what they do. But, like, you don’t care, you don’t know anything.

The facts of my day would be my map coordinates and my texts, and that’s going to tell you only a very small aspect of my internal life. It’s going to tell you nothing about my internal world, unless I texted one of my girlfriends about something. But other than that, it just doesn’t tell that story.

Edna Meade Colson driving, date unknown [courtesy of the Amaza Lee Meredith Papers, Virginia State University, Special Collections and Archive]

SW: I’ve noticed this same thing in Mildred Thompson’s archive. She was a Black queer woman who fled the States, fled from discrimination, moved to Berlin, made a whole bunch of work, had shows, and then came back and bought a house in Grant Park, Atlanta. She taught at Atlanta College of Art, which was later purchased by SCAD. She also taught at Spelman. She was an educator, she was a painter, and she brought all of that knowledge back to her students and to ART PAPERS, where she was an editor. Now, I’m in residence at her estate.

AE: You live there?

SW: I don’t live there. I’ve stayed for a week at a time doing research. Melissa Messina, the curator of Mildred’s estate, renovated the top floor of the home to host artists. She has kept Mildred’s entire library. Her things are organized in boxes and flat files. She has an archive that is being pieced together. It’s just a crazy feeling to be among someone else’s things while trying to tell a story about it.

AE: Without seeing them move through it.

SW: Exactly, all to explain their impact and who they were. It’s so interesting.

AE: I hope people like it. Definitely very excited about it.

SW: Well, it’s in history.

AE: That’s what’s really exciting.

SW: No one’s done it before. You’re the first one.

AE: It’s hard to believe that. When I say it, I’m, like, “I’m missing something. Someone did something that I don’t know about. And they’re going to come for me.” But I hear you.

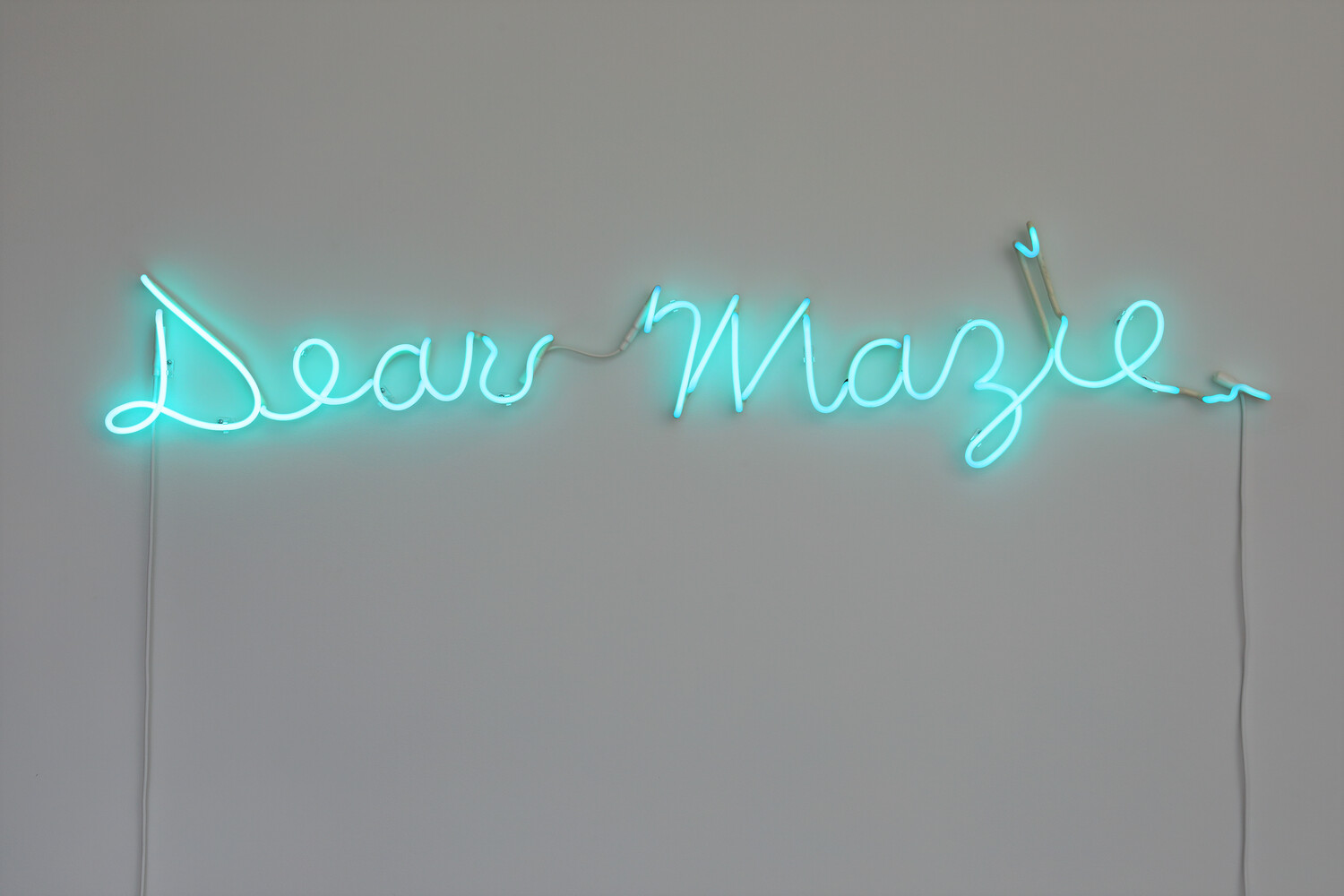

Dear Mazie, detail view of the neon sign, 2024 [photo: David Hale; courtesy of Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University]

Samaira Wilson is an artist and writer. She received her BA in Studio Art and Global International Studies from Bard College. She regularly contributes to Elephant Magazine, and for stints at a time, is a resident at the Mildred Thompson Estate Residency, developing her art practice.