Estamos Bien – La Trienal 20/21

Patrick Martínez, Defeat and Victory, 2020, stucco, neon, mean streak, ceramic, acrylic paint, spray paint, latex house paint, banner tarps, ceramic tile, tile adhesive, plexiglass, vinyl decal, family archive photo collage, and led sign on panel

84 x 192 inches [photo: Martin Seck; courtesy the Artist; Charlies James, Los Angeles, and el Museo del Barrio, New York]

Share:

Following a year of heightened calls for corrective change to social imbalances in the United States, particularly as they are reinforced by institutional structures, El Museo del Barrio provides artists with a platform to question the status quo and societal norms in Estamos Bien – La Trienal, a revival of the series once known as The (S) Files, which was formerly a biennial survey exhibition of Latinx artists, and began in 1999. Some work is presented digitally, expanding the survey past the walls of the museum and allowing the curators to display an even broader representation of Latinx art and community. The curators—Rodrigo Moura, Susanna V. Temkin, and Elia Alba—offer audiences a cornucopia of artistic practices and themes, including 42 artists and collaboratives/groups from various locales in the US and Puerto Rico.

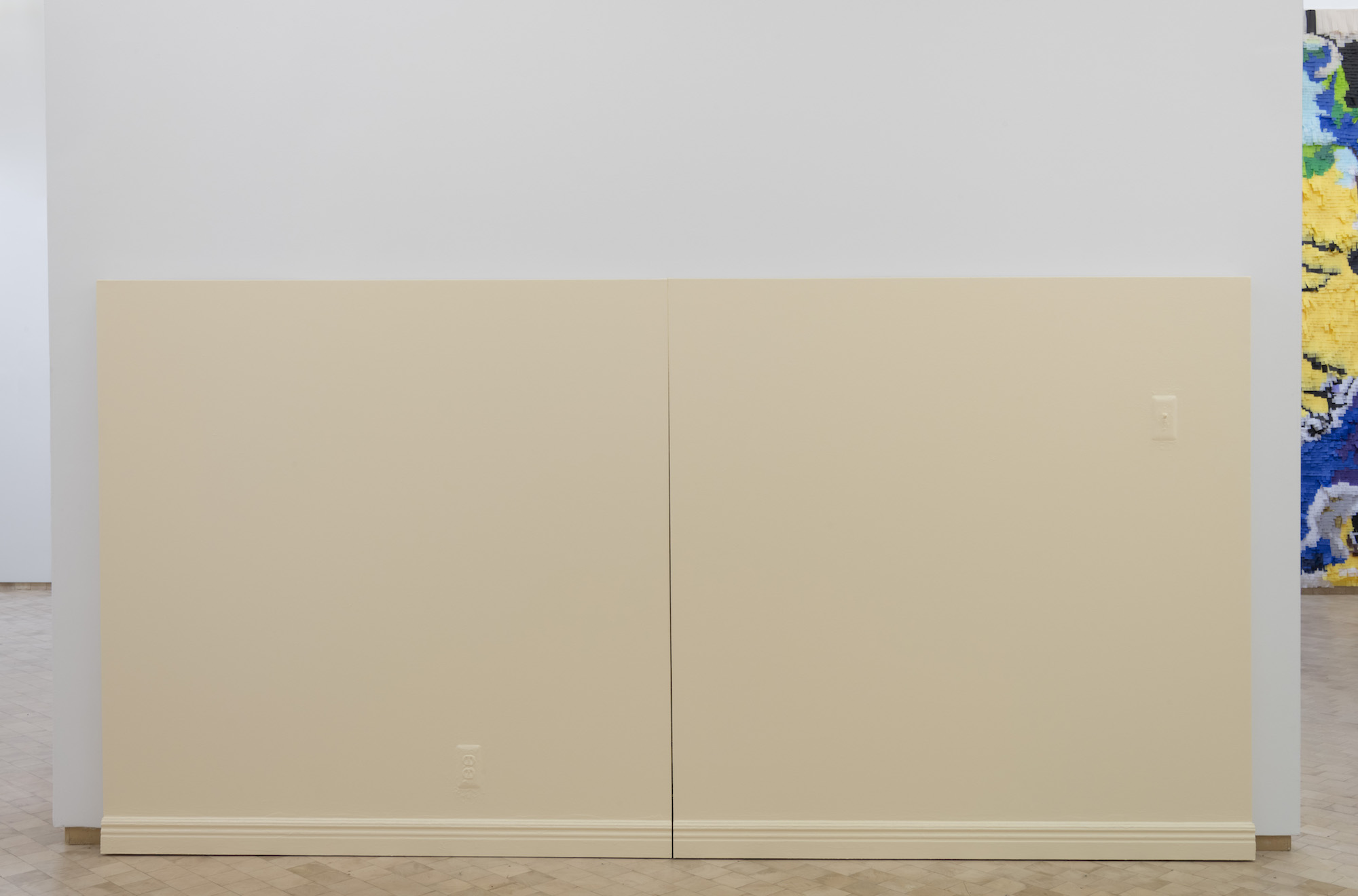

Fontaine Capel, “Wall Work,” 2021, electrical hardward, wood, wall paint on canvas, 66 x 132 inches [photo: Martin Seck; courtesy of the artist and El Museo del Barrio, New York]

One of the most intriguing works is Fontaine Capel’s Wall Work (2021), which rests on the floor, embellished with a light switch, a wall socket, and a long strip of baseboard across the bottom of two canvases. These elements are painted over with layers of off-white, almost-yellow wall paint—a hue that many New York landlords use to refurbish apartments between residents. In an exhibition full of works competing to be seen and considered, this painting blends into the gallery wall. As theorist Amelia Jones argues in Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts: to read an artwork queerly is to open up identification in order to yield new understanding. Of course, Capel is not actually seeking for the work to be overlooked. Rather, the painting’s camouflage becomes a signifier for those who are rendered invisible by the housing system—priced out, evicted, or made homeless. For many, life in bustling cities is precarious, and Capel quietly calls out those who fail to see the problem, or worse, choose to ignore it. Hiding in plain sight is a queer stratagem to provoke thought.

Another formally subtle work that questions institutions and their systems is Vick Quezada’s installation of clay lunch trays, Table Remains (2018). The trays allude to the dehumanizing conditions of prisons, schools, hospitals, and other institutional settings. They are stand-ins for people—standardized into numbers and simplified into leftovers. Quezada hand-kneads and pit-fires each tray, creating unique burn marks and coloration. The trays serve as reminders that their users are individuals, whose lives differ from one to the next. Both Capel and Quezada make visible the transiency of lives lived, honoring them with attention.

Vick Quezada, “Table Remains,” 2018, ceramic trays, variable dimensions [photo: Martin Seck; courtesy of the artist and El Museo del Barrio, New York]

As an avid researcher of African diasporic spiritual practices, Nyugen E. Smith creates a new perspective on the Island of Ayiti—known today as Hispaniola—in his work, Bundlehouse Borderlines No. 6 ( _emembe_ ) (2008), by rotating the island 90 degrees clockwise. He dots the island with small tent-like settlements that could be huts or temple structures. These spiritual tributes and signs are an offering to the land and the people of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. While the work is for everyone who comes before it, it is more meaningful to the islanders who could readily understand his specific gesture.

Flanking Smith’s piece are works by Sandy Rodriguez and Yelaine Rodriguez (no relation). Yelaine honors the orisha from Santería—a syncretic religion within African diasporic communities—by creating her own rendition of the spiritual deity through costuming. Her regal orisha stands at the center of the image, looking off into the distance, as if seeing into the future, with a sense of calm, poise, and beauty. Nearby, Sandy has recorded and diagrammed indigenous spiritual medicine women and the local Mexican plants for posterity, using amate paper, which is handmade using traditional Mexican techniques, and sourced from a family in Mexico that has produced the paper for several generations. Paying homage to the healers, Sandy acknowledges the roles that women play in their communities.

Estamos Bien – La Trienal 20/21, installation view [photo: Martin Seck; courtesy of El Museo del Barrio, New York]

Juan William Chávez made a pandemic edition of his Survival Blanket series (2017–ongoing) arranging a mesa (ritual altar) on the reflective aluminum surface of the titular material. On a small monitor, footage both of beekeeping and of the protests ignited by the 2014 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson calmly points out the horrors of colonization and its ongoing impact. The myriad of unconventional survival objects—including a hand-embroidered weaving with the word “Pandemic”, mates burilados (hand-carved Peruvian gourd or pumpkin vessels and pots), shaman waq’ollo knit masks, and plants and nests from Chávez’s garden in St. Louis, MO—have been gathered to acknowledge and heal the larger interrelated societal ills. Survival Blanket (Pandemic) (2021) suggests that only through grace and peace of spirits will one find one’s way through the current social injustices and global ecological imbalance.

Juan William Chávez, “Survival Blanket (Pandemic),” 2020, monitor, beekeeping equipment, gourds “mate,” tapestry, dried plants, variety of found objects, Peruvian knitted masks, survival blanket, variable dimensions [photo: Martin Seck; courtesy of the artist and El Museo del Barrio, New York]

The curators opted to foreground joint efforts in La Trienal. Four out of the five online projects, made available prior to the official opening of the physical show, spotlight collaborations. Poncilí Creación, a collective primarily composed of twin brothers, performed on the streets of Puerto Rico during the pandemic to protest for the changes necessary on the island. Lizania Cruz’s Obituaries of The American Dream (2020) and Collective Magpie’s The Race Survey (2020) collect stories from online participants. The former asks, “When and how did the American dream die for you?” Powerful responses to that prompt are incorporated into a free newsprint. The latter is a poetic reckoning with race, as dictated not by standard governmental forms, but by how the participants feel about race.

The communities that the artists form with their subjects is the subject of Se Que Fue Así Porque Estuve Allí (2020) by xime izquierdo ugaz. The queer, non-binary artist collaborates with their chosen family to create intimate portraits, which are included in the exhibition both online and in the galleries. On the project website, the sitters are called “fierce, gorgeous, Black & Brown, queer and trans kin.” Like family photos hung at home, the mixed set of picture frames seems to elaborate upon individual personalities, while also presenting them as a collective.

Poncili Creación, “Somxs Podemxs,” 2020, video documentation of a durational performance, 25:18 min [courtesy of the artist and El Museo del Barrio, New York]

María José, “Amor,” 2020, archival ink jet print, 24 x 18 inches [courtesy of the artist and El Museo del Barrio, New York]

María José’s contribution, Amor (Love) (2020), is an archival inkjet print of two male-presenting lovers embracing. They are on their knees at the center of an intersection: A paved road crosses a small stream, possibly rainwater runoff from Puerto Rico’s storm season. This temporary meeting point of the natural and the constructed gently prompts viewers to consider the simultaneous precarity and defiance of trans lives.

Carlos Martiel’s performance, titled Monument I (2021), takes a darker tone. In a stark, white gallery, flanked by five columns forming a semicircle, Martiel stood on a gallery pedestal like a statue. A wall text explains that the artist had dipped his nude body in the blood of

migrant, Latinx, African American, feminized, Native American, Muslim, Jewish, Queer, and Transexual bodies considered as “minority” or marginalized groups in the United States by Eurocentric supremacist discourses.

Due to Covid-related precautions, the work is presented as a 30-minute video documentation alongside the pedestal where Martiel stood, his bloody footprints visible on its surface. Martiel recognizes the trauma that is inflicted upon oppressed peoples and monumentalizes the resulting anguish with a simple, visceral gesture.

Francis Almendárez’s Dinner As I Remember (2016) is a three-minute video slideshow of family photos featuring eating and cooking. The work concludes with narration by the artist:

I look at these pictures, and as shitty and cliché as they are, they do make me realize the value of cooking and sharing a meal, the labor, love, and care that goes into it; the history, hybridity, and complexity of the recipes, and the power and agency they possess. Because as individual ingredients, they are just that, but as a collective, they could amalgamate to something more.

Dinner As I Remember sets the tone for an exhibition-as-amalgamation of Latinx voices.

Estamos Bien is a pleasure to visit, a well-rounded show centering themes like (in)visibility, spirituality, community, and queerness. The curators have thoughtfully presented a generation of Latinx artists that aims to change our comprehension of one another’s experiences.

Sophia Ma is an emerging curator. Most recently, she participated in SPRING/BREAK Art Show New York 2020, and she interned for the Arshile Gorky Foundation to work on the artist’s catalogue raisonné. For her graduate thesis at Hunter College, CUNY, she wrote about the work and spiritual practices of abstract painter Bernice Lee Bing. Ma worked in development, programming, operations, and administration for the Museum of Chinese in America. Currently, Ma is researching for a manuscript on landscape architecture, due for publication by Rizzoli New York in fall 2021.