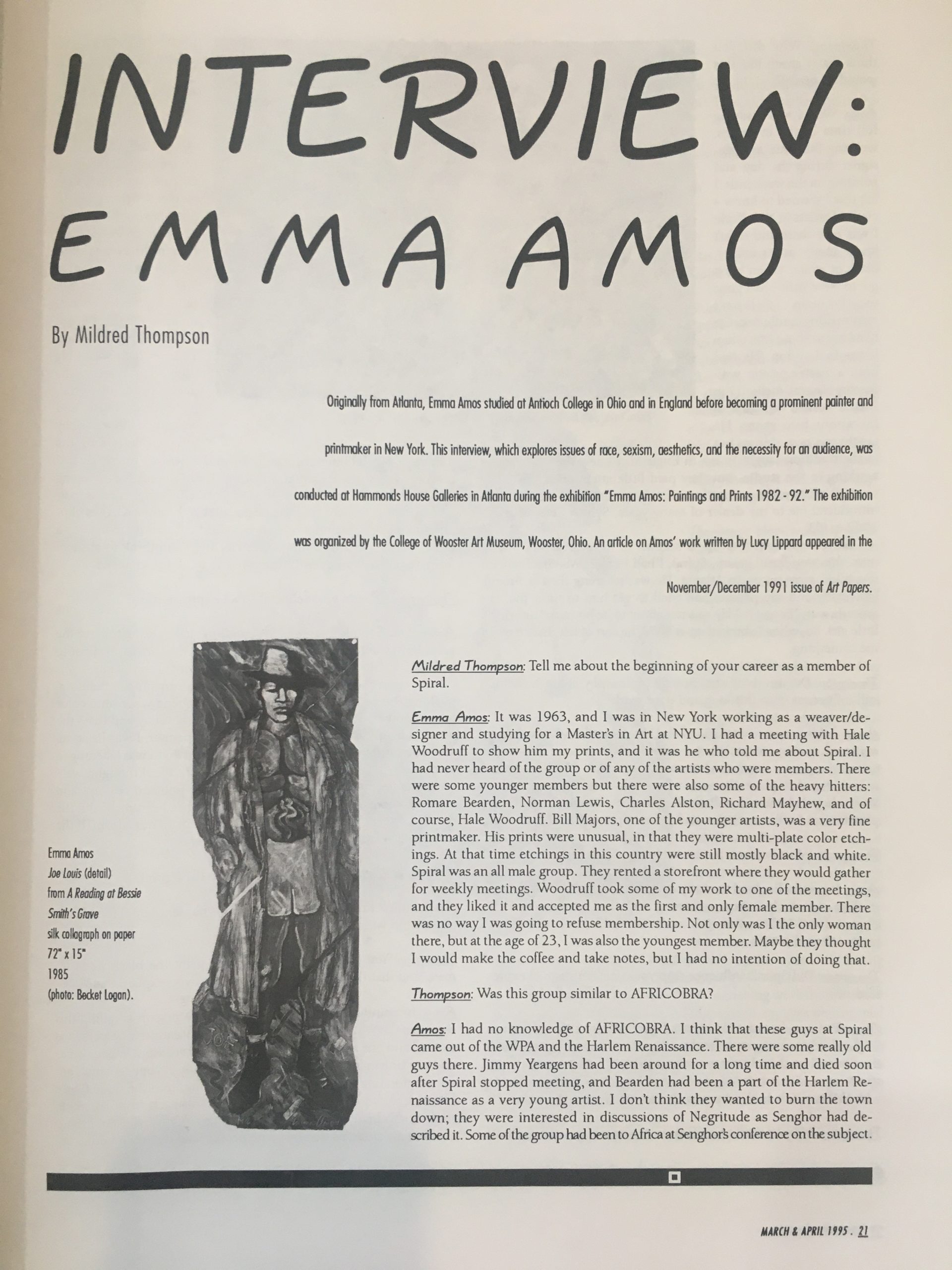

Emma Amos

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS March/April 1995, Vol. 19, issue 2.

Originally from Atlanta, Emma Amos studied at Antioch College in Ohio and in England before becoming a prominent painter and printmaker in New York. This interview, which explores issues of race, sexism, aesthetics, and the necessity for an audience, was conducted at Hammonds House Galleries in Atlanta during the exhibition “Emma Amos: Paintings and Prints 1982-92.” The exhibition was organized by the College of Wooster Art Museum, Wooster, Ohio. An article on Amos’ work written by Lucy Lippard appeared in the November/December 1991 issue of Art Papers.

Mildred Thompson: Tell me about the beginning of your career as a member of Spiral.

Emma Amos: It was 1963, and I was in New York working as a weaver/designer and studying for a Master’s in Art at NYU. I had a meeting with Hale Woodruff to show him my prints, and it was he who told me about Spiral. I had never heard of the group or of any of the artists who were members. There were some younger members but there were also some of the heavy hitters: Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Charles Alston, Richard Mayhew, and of course, Hale Woodruff, Bill Majors, one of the younger artists, was a very fine printmaker. His prints were unusual, in that they were multi-plate color etchings. At that time etchings in this country were still mostly black and white. Spiral was an all male group. They rented a storefront where they would gather for weekly meetings. Woodruff took some of my work to one of the meetings, and they liked it and accepted me as the first and only female member. There was no way I was going to refuse membership. Not only was I the only woman there, but at the age of 23, I was also the youngest member. Maybe they thought I would make the coffee and take notes, but I had no intention of doing that.

MT: Was this group similar to AFRICOBRA?

EA: I had no knowledge of AFRICOBRA. I think that these guys at Spiral came out of the WPA and the Harlem Renaissance. There were some really old guys there. Jimmy Yeargens had been around for a long time and died soon after Spiral stopped meeting, and Bearden had been a part of the Harlem Renaissance as a very young artist. I don’t think they wanted to burn the town down; they were interested in discussions of Negritude as Senghor had described it. Some of the group had been to Africa at Senghor’s conference on the subject.

MT: Why did you think that a group like this would be useful?

EA: Well, I was studying full time in the evenings, working full time as a designer during the day, and painting on the weekends. I felt that I wanted to know a circle of artists in New York; I was new there and didn’t know many other artists, black or white. When I first got to New York I had gone to Letterio Calapai’s printmaking studio because I had heard about him when I was in London. He had been a master printer with Stanley Hayter’s Atelier 17 in Paris. I worked with Calapai for about two years. He taught me new things, but in the tradition taught to me in England. I knew the other artists working in the studio, but they paid little attention to me. They were all white males except for one white woman, Doris Lee, who introduced me to my dealer of many years, Sylvan Cole, in about 1962 or ’63.

So when I went to NYU, it seemed to me a great addition to meet this wonderful group, Spiral. I had known Woodruff when I was a kid growing up in Atlanta. He was teaching then at Atlanta University and my parents had tried to get him to tutor me. His attitude was. “Forget it.” He was not about to be othered tutoring a little girl. So, when I showed up at NYU, he sort of felt that he owed me something.

MT: Do you think that Spiral’s philosophy about Negritude still influences your thinking and your work?

EA: I think our conversations and discussions had to influence my work in many ways. When I came back from London and first joined the group, I was an abstract expressionist. I had become so in London, of all places, because when I was there I saw the famous Whitechapel show, where Pollock and others brought abstract expressionism to the continent, and I was impressed by those works.

MT: What years were you studying in London?

EA: I went to England to study etching in 1956-57 while I was a student at Antioch College, returning to Ohio to graduate in 1958. Then in 1958-59 I worked again at the Central School in London to receive their diploma.

MT: Did Spiral’s influence stop your work in abstract expressionism?

EA: Perhaps, because I’d been a figure painter before I went to England. My training at Antioch had continued my long interest in the figure, but then I became impressed with what I saw the abstract expressionists doing. At Central I studied abstract painting with William Turnbull, who was also David Hockney’s teacher.

MT: Did you think that abstract expressionism was too limiting for you? Was it a conscious decision to give it up? What did Spiral think of your abstract style?

EA: Well, you have to remember that the group was not particularly figurative. Norman Lewis, after having been a figure painter in the ‘30s, became known as a fine abstract expressionist, and mostly left the realistic figure. He was a member of the Willard Gallery along with Mark Tobey, which was a big thing then. Bearden, the heavy hitter of Spiral, had written music and was much influenced by Stuart Davis and his friendships with Ellington, Strayhorn, and other jazz giants. He had bee a lyrical abstract painter, showing at Sam Kootz’s Gallery along with Baziotes, Holty Motherwell, and Gottlieb. Romy’s most important work using photomontage began after he brought a bag of clippings to a Spiral meeting to see if we could collaborate in making a piece. This act changed him as well as me. I still think in abstract form; to be an expressionist, though, my work has changed.

MT: How do you define abstract expressionism?

EA: Well, I think that it’s paint handling, it’s wanting to have the paint flow, wanting it to be on the surface of the canvas, and not to seek depth, but bring the action right up front. In England it was called action painting. It’s the action of the arm in the painting, pushing the paint around, seeing what happens when one color meets another. That is basically the way I paint today and that’s the way I’m happy. But when I became a figure painter, I was listening to all the rumbles of the civil rights movement and I was listening to all of these smart old guys talking about Negritude. I thought, well, there has got to be some way of doing this political concept and painting expressively. I never did sketches ahead of time. I did the drawings directly on canvas. I tried never to paint out a form. If the image didn’t work, I would start a new canvas.

MT: Why are you so involved with the figure?

EA: I think I use the figure because it is harder to do. I found that abstraction was too easy, too arbitrary.

MT: You have said that you don’t paint the black nude female, and that the image disturbs you. Can you explain that?

EA: In painting the nude model, that one person is telling this other person what to do. It is not an equal situation; one person is clothed and one isn’t. Your clothing is your protection. When someone is sitting in front of you naked, that person is your servant. I am not comfortable with the concept of painting from the nude figure anymore. I did as an art student and I still teach from the nude occasionally in my drawing classes at Rutgers University. But I try to instill in my students that these are people, and that their bodies are more than bones and flesh. I reject most nudes as sexist, but before becoming conscious of my admitted bias, I had rejected black female nudes in particular. Their figures unclothed reminded me too painfully of the slave market, of black people as objects, of women as the powerless “other.” I like the concept of dressing the figure, of clothes as culture.

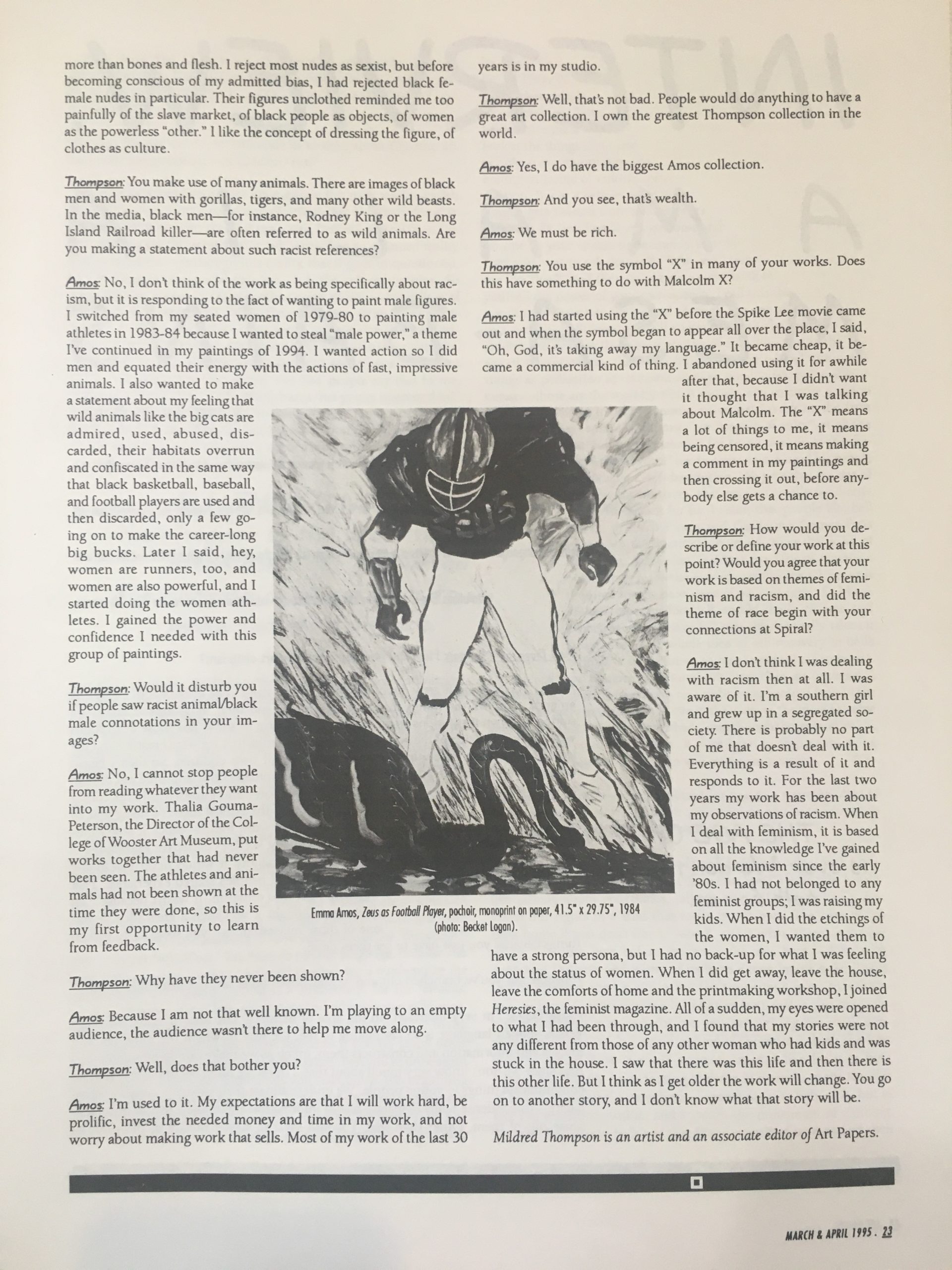

MT: You make use of many animals. There are images of black men and women with gorillas, tigers, and many other wild beasts. In the media, black men-for instance, Rodney King or the Long Island Railroad killer-are often referred to as wild animals. Are you making a statement about such racist references?

EA: No, I don’t think of the work as being specifically about racism, but it is responding to the fact of wanting to paint male figures. I switched from my seated women of 1979-80 to painting male athletes in 1983-84 because I wanted to steal “male power,” a theme I’ve continued in my paintings of 1994. I wanted action so I did men and equated their energy with the actions of fast, impressive animals. I also wanted to make a statement about my feeling that wild animals like the big cats are admired, used, abused, discarded, their habitats overrun and confiscated in the same way that black basketball, baseball, and football players are used and then discarded, only a few going on to make the career-long big bucks. Later I said, hey, women are runners, too, and women are also powerful, and I started doing the women athletes. I gained the power and confidence I needed with this group of paintings.

MT: Would it disturb you if people saw racist animal/black male connotations in your images?

EA: No, I cannot stop people from reading whatever they want into my work. Thalia Gouma-Peterson, the Director of the College of Wooster Art Museum, put works together that had never been seen. The athletes and animals had not been shown at the time they were done, so this is my first opportunity to learn from feedback.

MT: Why have they never been shown?

EA: Because I am not that well known. I’m playing to an empty audience, the audience wasn’t there to help me move along.

MT: Well, does that bother you?

EA: I’m used to it. My expectations are that I will work hard, be prolific, invest the needed money and time in my work, and not worry about making work that sells. Most of my work of the last 30 years is in my studio.

MT: Well, that’s not bad. People would do anything to have a great art collection. I own the greatest Thompson collection in the world.

EA: Yes, I do have the biggest Amos collection.

MT: And you see, that’s wealth.

EA: We must be rich.

MT: You use the symbol “X” in many of your works. Does this have something to do with Malcolm X?

EA: I had started using the “X” before the Spike Lee movie came out and when the symbol began to appear all over the place, I said, “ Oh, God, it’s taking away my language.” It became cheap, it became a commercial kind of thing. I abandoned using it for awhile after that, because I didn’t want it thought that I was talking about Malcolm. The “X” means a lot of things to me, it means being censored, it means making a comment in my paintings and then crossing it out, before anybody else gets a chance to.

MT: How would you describe or define your work at this point? Would you agree that your work is based on themes of feminism and racism, and did the theme of race begin with your connections at Spiral?

EA: I don’t think I was dealing with racism then at all. I was aware of it. I’m a southern girl and grew up in a segregated society. There is probably no part of me that doesn’t deal with it. Everything is a result of it and responds to it. For the last two years my work has been about my observations of racism. When I deal with feminism, it is based on all the knowledge I’ve gained about feminism since the early ‘80s. I had not belonged to any feminist groups; I was raising my kids. When I did the etchings of the women, I wanted them to have a strong persona, but I had no back-up for what I was feeling about the status of women. When I did get away, leave the house, leave the comforts of home and the printmaking workshop, I joined Heresies, the feminist magazine. All of a sudden, my eyes were opened to what I had been through, and I found that my stories were not any different from those of any other woman who had kids and was stuck in the house. I saw that there was life and then there is this other life. But I think as I get older the work will change. You go on to another story, and I don’t know what that story will be.