Earth Studies

A satellite image of Earth with nearly all land masses obscured from view.

Share:

Despite the diminutive size of our bodies, the Earth, in all its grand scale and complexity, is managing to grow inside us. The device you might be reading on—itself a refined aggregate of raw Earth-matter—has helped to recontour how we conceive of our world and fashioned a new sense of planetarity in the process. These same techno-mediums that shrink time and space by connecting our lives across oceans have, in doing so, inadvertently stranded us on individual islands. The dispatches we receive describe all manner of global calamity, sculpting our fever dreams of worlds-on-fire into perfect doom spirals. We follow these spirals down to greater depths, becoming groomed in their horrors.

These devices, and the kaleidoscope of messages they compel to our eyes, have become part of a planet-scaled gymnasium in which our imagination of Earth is being reshaped. Planetarity’s curriculum is what you might expect: climate change; a pandemic; the restoked specter of nuclear war; the ongoing wreckage of Globalism 1.0; world-in-your-pocket apps such as Google Earth; mass migrations and border crises; the emergence of the Anthropocene; colonization and its aftermaths; the project of de-anthropocentrism; the sixth mass extinction; and, of course, more. These concepts—part of our generation’s polycrisis—become a background beat to an increasingly complex song that the citizenry of Earth is learning by heart. We have become planetary beings, even if we haven’t made it out of the apartment much this week.

Regardless of our exact geolocation or whether our passport remains mostly unstamped, our bodies and souls have become bound to an intersectional web of planetary-scale processes. We are participant-observers in an Earth Story that we’re witnessing in real time and co-authoring as tragicomic NPCs. And, as increasingly post-human divisions of labor become splintered and hyperspecialized, our skills as tool- and object-makers deliver us back into a world that we no longer understand or trust; in its place emerges a bewildering planetary mirage. Its inner machinations, histories, and counter-histories are available to us at any moment as a vast catalog of expanding Wikipedia entries, Google searches, TikTok opines, OpenAI–inflected think-pieces—more and more indecipherable as a cosmology of meaning. That same phone in your hand—perhaps the most daily and ubiquitous object in our lives—encapsulates an aggregate complexity that no single person who has ever lived could build or explain. At this, we mostly shrug.

Now, our technologies demand of us everything, beckoning us to invent increasingly fantastical units of measure to quantify ever larger and ever smaller fragments of earthly time and matter we can’t see or register. The effect manages the impossible feat of taming Earth’s wanton forces while counterintuitively making them also less and less relatable. To “observe” objects as small as electrons necessitates a clock measuring time in femtoseconds—or time elapsing inside a million-billionth of a second. But this is achingly slow compared to the even shorter attosecond, a temporal unit so small that its inverse relationship to a single human heartbeat would equal the age of the entire universe, some 14 billion years. At these scales, reality becomes so alienated from our what’s-to-eat corporeality that new, never-imagined entanglements surface at every imaginable scale, challenging our coherence as beings.

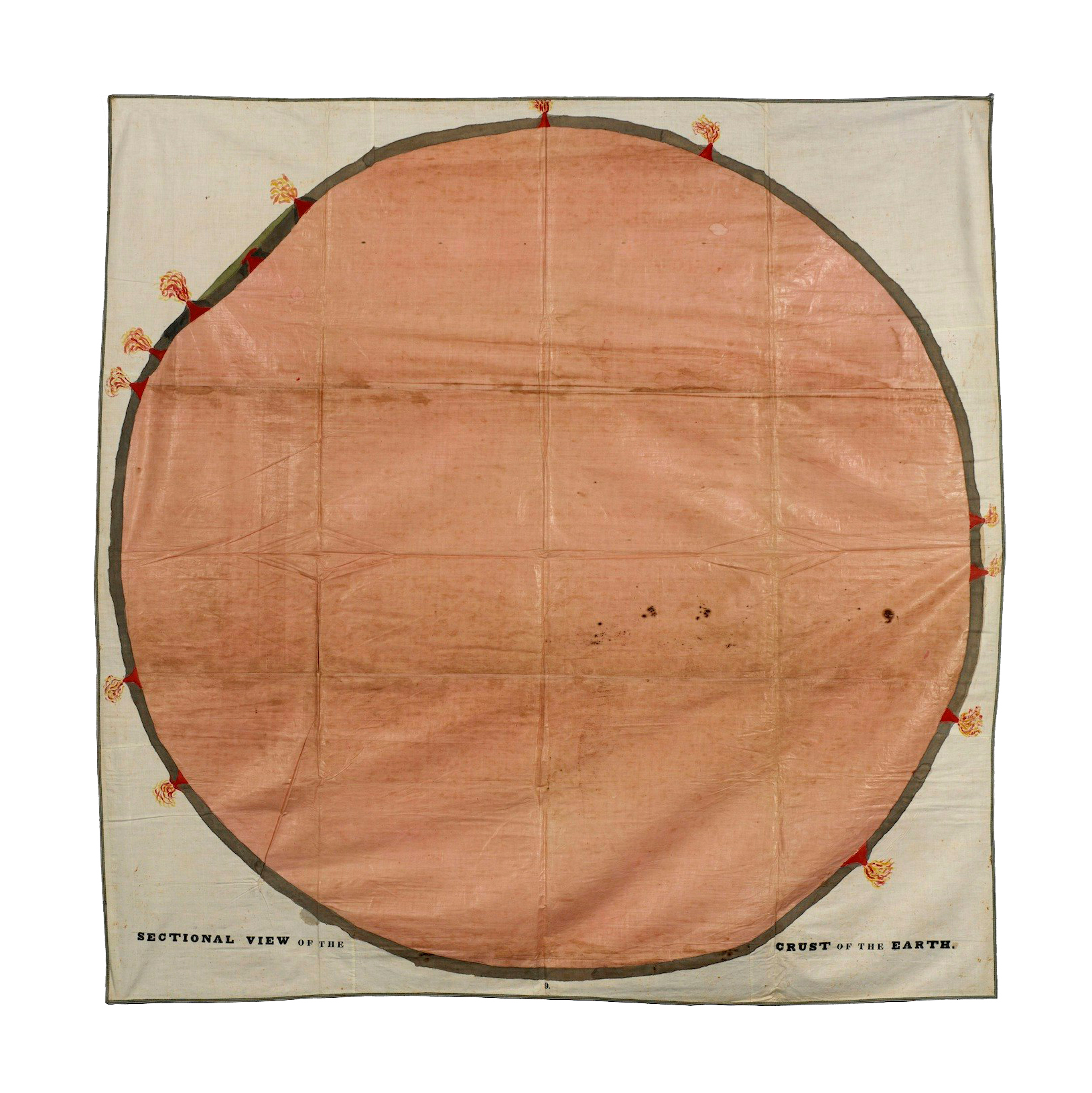

World as Subject

We often use the terms world, planet, Earth, and globe interchangeably. More functionally, they might be conceived as circles in a Venn diagram, each describing unique geographies. At the risk of oversimplifying: planet holds our cosmological relations within interstellar space; Earth relates to a cauldron of possible biologic and geologic interactions; and globe draws upon invented borders that encode ever-changing political and economic interdependencies. World, though, occupies the overlapping Venn-sliver. There, simmering within the electrochemical stew of our minds, we can distill aspects of Earth, planet, and globe into a working cosmovision—our place within this much larger place. Simply, the world is our unique and subjective experience of living on planet Earth.

World is an ethos we inherit and a place that we co-create amid the living. It—along with the mystery, misery, and majesty of our conscious bodies—is the oldest and perhaps the most durable subject we have. Every generation, especially its artists, inadvertently come around to contemplating a songbook of shared subjects that, in their unanswerable existentialism, form a baseline of human experience: What is this body I have? What are these feelings that seem to possess me? Around me, who are these people and what is this stuff? How did it get here, and is there more? How should I live before I die? What happens next?

World, with its provocation of origins, limits, and endings, encourages our most profound and enduring questions. Yet, in doing so, it exposes them as age-old, belonging to every being that has lived. This generational cycle of thematic return is a reminder that, on Earth, nothing is missing; by definition, it’s all already here. But, by virtue of this wholeness, producing something new becomes a near-magical feat of transformation. This omnipresent creative friction by which our acts of living are tremendous, but also tremendously ordinary, forms the baseline of our shared existence. As we cycle through the chores of our day, we do so in parallel with 8 billion people on Earth, miming one another’s existence in mostly congruous ways—waking, peeing, scrolling, eating, speaking, walking, working, resting, dreaming, worrying.

And yet, that we’re actually alive is, by all measures, unbelievable. With this revelation in mind, the daily-ness of life—brushing teeth, finding matched socks, scrambling eggs, laboring for roof and bread—becomes a mismatched homage to the feeling of profound interconnection that exists, mostly dormant, just beneath the meniscus of living.

Being, alive

Throughout time, central to being alive—of finding pleasure and meaning in our aliveness—is the cultivation of an always-becoming and enchanted world: an Earth of unfathomable creativity, surprise, and dimension, whose delights and contradictions are unfolding before us, but also within us, in which we feel and find connection. The planet’s elements and compounds, minerals and metals exist as a common logic system for everything that has ever gained form: flintstones and falcons, pottery and pizza, Reeboks and roses, hurricanes and honey.

Within our veins and bones are iron, calcium, and magnesium leached from ancient rock. There’s sulfur in our hair, phosphorus in our fingernails, salt from unnamed prehistoric seas in our tears and sweat. Water, once locked inside Earth’s mantle, composes the bulk of our mass. We are Earth. Its primordial material storehouse is held within us—down to the anthropogenic pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and forever chemicals now detected in our blood.

As Earthen-life has always known—but, as moderns, we must continually relearn—matter at every scale is erotic, desiring above all to come into contact, to commune, and to transform: the salience when contact transforms into connection; the feeling rising inside us as a glow, like the grace of a lover’s valent pull. Connection reshapes us by holding us in contact, and by renewing us as something actually new. What we’re feeling—the motion of change—is the ambient logic-core of Earth.

The pandemic reminded us that the air entering and exiting our lungs is ours only for a moment—a carnal exchange of invisible Earth, slipping in and out of our bodies, maintaining our lives. The artifact of this exchange is a new molecule—CO2—which, as it leaves our lungs, equalizes across the entire Earth in two days’ time. Your humble breath displaces itself over a vast dominion of space, spreading through river valleys, deserts, crematories, and bedrooms. The separateness we comfortably imagine while sitting in our homes, away from burning forests, enslaved livestock, or rising seas—or even each other—is a worlding fiction we inherited.

Becoming Planetary

For as long as life has existed, slow-motion geologic forces that transform the earth have marched, in lockstep, with the evolutionary energies transforming our bodies. We—the living—exist on the outer rim of a vast process of biologic becoming. This growing-into-ourselves has occurred over 100,000 ancestral cycles, existing alongside slowly atrophying capacities, holding countless adoptions, transcribed in our bodies, informing what we are. But, over the last handful of generations, this even geologic/biologic flow has been disrupted, creating all manner of frictions playing out upon Earth and our bodies.

We leave behind more artifacts of our presence on Earth than just our genomes. We transform things. Our domestication of fire as a proto-technology is one, and this act was our first step toward becoming planetary. Whenever we create fire, we engineer a small tear in time, triggered by the hyperbolic release of cosmic energy held within objects that have lived and died all around us. Flame is a glowing portal that has entranced us for millions of years.

Our long-form dance with Earth’s materials eventually led us inside the planet itself, to unlock its geotemporal archive of time and energy stored within the petro-record. A fulcrum point emerged at which our accrued inventions and discoveries of the material world, coupled with the sudden release of millions of years of accrued time locked within coal and oil, disrupted the trance-speed hominids had evolved within for 3 million years, destabilizing planetary climatic systems in the process.

In the 1990s, sociologist Anthony Giddens, recognizing a set of changes afoot, argued that globalization is “a shift in our very life circumstance” involving “the intensification of worldwide social relations.” This intensity might be interpreted as a simple equation: acceleration increases change exponentially. The illusion of time speeding up is partially due to the number of discrete and quickly emerging relationships we must juggle—the political, professional, technological, ecological, social, and others. At every moment, we are charged to track, study, synthesize, adjust, and reintegrate change without pause—or risk peril. In totality, we must now reconstitute our concept of World, almost daily.

Clocks

In the primordial sense, our bodies are calibrated to the planet’s rhythms. As the ground beneath us turns toward the sun, we rise to greet the morning, along with most of our neighbors as a continuous anthropomorphic wave rippling around the earth. This ritual has occurred as an unbroken continuum of waking and sleeping for all of human history. Although our individual biologies are still diurnally synced to ancient planetary motions, we have punctured that synchronicity within the epoch of Globalization 1.0 and its anti-human wreckage.

For Earth to function as a global market—its substances unendingly reconditioned as resources fabricated into uncountable varieties of objects that will be pitched to us as goods, hacking our desires and bank accounts—our embodied experience of time first had to be dismantled. In its wake, Coordinated Universal Time conscripted us to a single clock, monolithically held in agreement across borders at the scale of the planet. Its emergence birthed the human nightmare we colloquially call “24/7”—a veil of global time-logic that encourages a ceaseless loop of extraction, exploitation, manufacture, trade, labor, content production, and consumption, in which our sleep schedules, sabbaths, holidays, celebrations, convalescences, dalliances, and meanderings are traded for a uniform calendar of syncopated, hyper-scheduled movements. Without any pause, and with the possibility of doing everything whenever, one sort of time ends, and another begins.

Although we are still living through this transformation, 24/7 has been a dress rehearsal for a battery of new temporal blows that our bodies and minds are just beginning to absorb. Our commonsense experience of chronology is hiccupping into an abstract, algorithmic one—a chronology that blurs the continuity of linear sequence into a drunken slurry. Sometime in 2016, within the envelope of the first post-truth election, the way most of us shared and received information changed underfoot. On our devices, we might once have managed to scroll and reach a controlled end of content, upon which we encountered the by-now-alien message: “You are all caught up.” In 2024, these five words are already a relic of a bygone internet, one that Gen Alpha will find hard to believe ever existed. Now, we scroll to nowhere by design, sliding through posts by randos and obscure businesses fed in loopy sequence, contradicting the shared arc of lived time. And in this hell, our behavior is, of course, robotically noted—innocuously slowing your finger over an image reconditions your algorithm, re-divines your future.

Of course, internet algorithms groom us toward perpetual in-satiation. To generate space for continuous desire—more world—we must perpetually be hollowed out. This continuum, in concert with a globalized 24-hour content cycle, flattens time and geography. Suddenly, our hardwired local empathies kindled toward family, friends, neighborhoods, and even more abstractly toward city, state, or country, are recast to include more speculative empathic connections at a global scale. We are linked to people and places that, odds are, we might never visit or meet. The possibility of techno-encouraged empathy offers an aching promise for radical human connection at global scale, but cast within 24/7 algorithmic intensity, our attentions are flayed by a litany of simultaneous horrors, often playing out thousands of miles away, and in every direction. Instead of building the urgency to act, our minds might be scheming against our better intentions, developing an internal immunity that inoculates us from doing—or even feeling—anything at all.

Now, years into this experiment, the result for many resembles paralysis, reproducing the same result—inaction—as if we hadn’t received the news at all. Except now, our inaction is couched within compounding guilt and dismay, that, if left unexamined, metastasizes into planetary pessimism. We now internalize countless horrors at a distance—events that just a half-generation ago would remain mostly undisclosed. The Thwaites Glacier might be cleaving, millions are displaced by the civil war in Sudan, “US asks China to tell Iran not to retaliate against Israel,” children play in the bombed rubble of their former homes, a knife attack at a mall in Sydney kills six, a broken dam washes away everything, a chemical leak kills millions of salmon, a piece of space debris falls on a house, bark beetles destroy a primeval forest in Belarus, a village in Kazakhstan crowdfunds for an MRI machine to detect tumors produced from Cold War nuclear testing. The warheads that these same tests produced are now aimed at your head—at everyone’s head, in perpetuity.

The Architecture of Edgelessness

Earth, a sphere, is, after all, edgeless. Although we’ve long agreed that we’re not living on a disk, our desire to continue unrolling Earth to its infinite, fractal limit—its final, gleaming, crystalline edge encoded in 32K resolution—remains unquenched. Perhaps there, we might finally encounter Earth’s “authentic truth,” and with it, ours. So, we draw, with new intention and frequency, the shifting contours of every coastline. We devise more powerful prosthetic eyes to lift us off our feet into the origins of space-time, where we might discover Earth’s provenience. We build machines to invert our gaze inward to a proportionally vast microworld of tiny particles. There, we coax atoms into weirder, longer chain molecules that might heal us, or kill us. We send sensors and probes and cameras to every depth, height, and crevice where we, ourselves, cannot go, receiving second-by-second readouts of Earth’s inner dreams, finally revealing its sentience. And now, thousands of low-orbit satellites composed of Earth’s elements—aluminum, titanium, gold, silver, chromium—stare back down at us, rephotographing the entire Earth and our antlike movements, ad infinitum.

It’s not difficult to conjure a future when the contours of all contours of Earth have been scanned at IMAX resolution; when every cave has been entered, its archeo-contents meticulously cataloged; when the peaks of every mountain, the canopies of all forests, and each square centimeter of the steppe are photographed, measured, and analyzed. Earth’s membrane, drilled at coordinated intervals for core samples, reveals the remaining secrets of geologic time. An armada of millions of tiny drones, no bigger than coins, fly in synced formation above the surface of the Atacama Desert, day and night, collecting 12K video, surface temperature readings, and moisture data.

As our panoptic world whirls on, in a not-too-distant moment, at a global GIS conference in Harare, rumor leaks of a cartographic glitch. A simple mapping error threatens to compromise the integrity of our effort to know Earth at all registrations. We discover that, in the equatorial Atlantic, nested within the Doldrums Fracture Zone, miles below where the last photon of sunlight peters out in saline blackness, a final stone has escaped our scans and catalogs. How could we have missed it? A submersible is boarded by the Earth’s remaining journalists. All seven of the world’s trillionaires. An artist and philosopher, for good measure. They steer along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Earth’s molten-magnetic scar. There, innocuously, the last uncatalogued stone. Perhaps mafic, basaltic in composition. The vessel’s titanium arm, lit by xenon light, extends. Under the weight of a million tons of ocean, the stone’s mass vanishes; it achieves a holy levity. The arm reaches out to grasp the stone, and in the moment before contact, all possibility blooms in our minds. Within this beautiful unknowing, the mystery of all worlds exists simultaneously. There, beneath the stone, hides perhaps a new crustacean? A microbe, or a sea worm of interest? No. There, in the wonder of thought, the stone encloses the lawn of your childhood, the dappled light cast on the sidewalk of your youth. It keeps secure your mother’s lost wedding band. There, under the stone, carved in serif font, your gravestone. Unseen beneath this rock, a round black portal—a hole inverting all light, cast infinitely deep into the cosmic abyss of the sky, at the bottom of the ocean. There, a total eclipse.

Seeing World

Writing in her 2013 essay “Too Much World,” and still in the pocket of techno-optimism, Hito Steyerl possessed a divining wand to forecast where we were headed:

With digital proliferation of all sorts of imagery, suddenly too much world became available. The map, to use the well-known fable by Borges, has not only become equal to the world, but exceeds it by far. A vast quantity of images covers the surface of the world … in a confusing stack of layers.

Steyerl could have only guessed the existential glut of pixels, the algorithmic and AI-induced drowning, that we now edge toward. As of this writing, every second there are 60,000 moments that we, as earthlings, collectively decide are worthy of a photo. Reading to the end of this sentence, close to half a million new images were just produced around the planet. Ours is an era so saturated with pictures, and pictures of pictures, that they have begun hijacking our direct, common sensorial experience of living on Earth. As our inner-image archive grows, so does the strain to register feeling.

Perhaps it isn’t strange that Gen Z-ers have reported seeing themselves as disassociated beings, as if they’re observing their lives as autofiction captured by some invisible camera. We now also tell of “feeling ourselves feel,” a statement that, in its elliptical, third-person swirl, underscores how emotions have become detached—arriving not from within but from the outside, as an afterimage beamed into us.

Pictures are not always optical artifacts. They off-gas deeper representations of our techno-connected existence, coded by cascading references, borrowed nostalgia, and meta-ironic winks, each psychically distancing us from realities big and small, creating a zombie class in its wake. We’re exposed to so many recordings of stock characters performing life at all its registrations that we risk templatizing all public and private life: birthdays, vacations, dinner out, drinking wine from a glass, arguments, holding hands, threesomes, proposing marriage. Life becomes something we LARP. Unable to mentally parse the 47 thousand recordings we have bio-indexed in our minds—of actors; influencers; TikTokkers performing the simple, out-of-time act of hand holding—we either dissociate or method act our own version.

At this horizon, a globalized affect seeps into how we use our bodies and find pleasure in them. Our once deliberately lived, volumetric presence in rooms and spaces becomes not just spectral but hallucinatory—even to ourselves. This numbness, and the emotional atrophies induced by it, are producing bizarre and confounding states of new consciousness.

But images have also destabilized our sense of scale. Earth has long been a vast, diverse container holding uncountable places, organisms, and events—happening mostly elsewhere, far away from us. Our mythopoetic cosmovisions, each in different ways, describe systems of belief for what exists on the “outside,” along with its ensuing compendium of mysteries. That outside is produced by a simple, wonderful, asymmetrical relationship: we all exist within small, short-lived flesh-bodies, unable to ascertain Earth’s all-at-once scope and dimension. We might reconcile the gap not as a structural flaw of our humanity but as an essential shadowland, where our imaginations have always rooted and flourished, a principal foundry for art’s creation.

Images, but moreso our pipelines of networked delivery, bestow us an ability to uncouple our eyes from our still-frame bodies. In this NatGeo-infused paradigm, we let them roam and drift, collapsing time and distance. We hallucinate, becoming birds in the clouds above Machu Picchu. We astral project into a Leopard 1 armored tank near Bahamut. We’re swimming with a pygmy blue whale in the Tasman Sea. Our eye, tethered to a drone, passes through Icelandic waterfall mist catching perfect sunlight where, as if by magic, a rainbow envelops us. Watching from our couch, piqued, we screen cap it. The planet’s 57,789th image that second.

Amnesia sets in.

The Raft

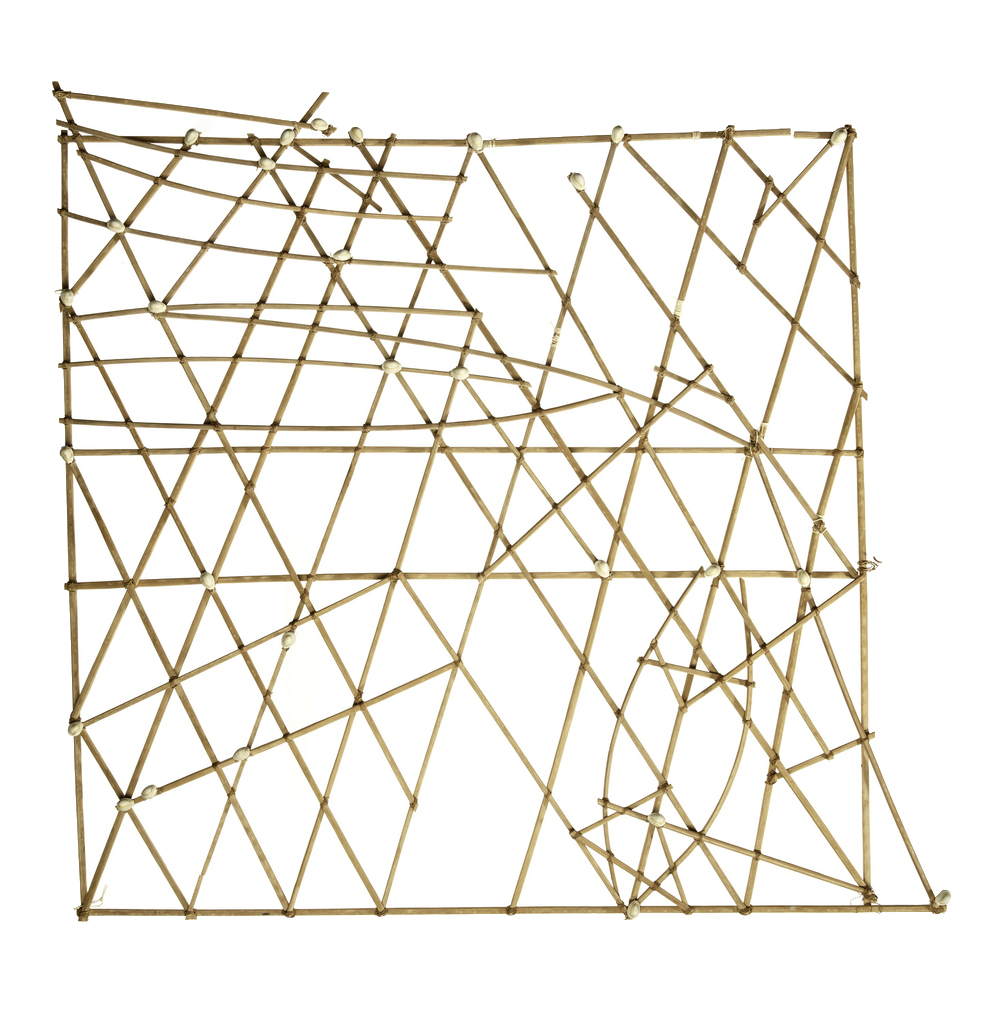

Story tells of a Raft, lashed together, of twelve wooden trunks: oak, spruce, maple, poplar, sycamore, birch, gum, and others. Each tree was delivered by the seas from ancient forests spread across Earth. In our lives, the Raft eventually magnetizes everyone to it—a beacon to our curiosity, our abstract dreams of elsewhere—honing our instincts toward the line of Earth’s horizon. The Raft, like other mytho-objects, speaks only in tongue. It whispers to us of shapes and colors beyond sight, compelling us to borrow it for a turn. It pulls us in, and we are, at once, beyond the waves.

Now, in the sea, the beginnings of a map appear in your hands, auto-drawing your path as if by magic. The map records your unique traverse, expanding as a constellation of islands—worlds—you encounter, objects and events you are touched by. Wind, dust, rivers, skin. Children, parents, brothers, lovers. Song, sculpture, ornament, dance. Folklore and gossip and rain; a coffin. A stairway, a home, a hall, a blanket, a coin. Language, spirits, the gods, no gods. In total, the map depicts a psychogeography whose expanding borders extend outward to the hinter regions of human possibility—where the trust you’ve learned and created for the world finds a fault zone.

Because this map is yours alone, its borders are grooved by the psychic pathways you have explored. When overlaid with maps of the 100 billion other sapien-souls who have ever lived, people who have also shared the Raft—our ancestors by another name—a diagram of surprisingly similar routes, passages, paths and shortcuts comes into focus. Mapped together, they make a total blueprint for all the regions of humanhood—our islands of shared existence, edged with the Promethean borders of what could be, where reason dissolves into unreason. Realities into fictions.

One night on the Raft, we drift into a dream. Floating above ourselves, we struggle to comprehend the islands—their relation, their meanings—as something whole and unified. In the dream, we hear distant notes of an impossible song echoing beyond sight. The sounds arrive in our body with such strange intensity as to overwhelm our capacity to hold them. The song remains as a resonance, vibrating anew, deep within us. We awake, and the Raft is gone. In its place, we sit cocooned within a subway train. Work-a-day. Earbuds. Patagonia fleece.

The song you heard has transformed; it’s real. It flows into your ears, channeling itself with such force and grace, discovering a space to live in your mind, unleashing its chemical serum, transporting your thoughts back to the ocean, to the Raft. Days later, still drifting in the afterglow of song, you wander to see an artist, a lecture that, before our eyes, becomes a performance, then magic, then an exorcism—words and strange actions telling of life impossible, limits torn up like paper, all summoned from the air by a small and living person who told us, without telling us, that there was still a way. That this—living, summoning, creating, defying—could still be accomplished, right before our eyes. And your eye, beyond this, having no option, summons a tear that travels down and crests on the ledge of your lip. We taste the ocean, the Raft. And later that evening, in the fireglow, crouched outside, you hear young, powerful artists speak of so many new forms and details and waves, and matter, and a dream of how it all may come together. You begin to disappear, like fire embers transforming to starlight. Then, an invisible breeze floats across all our bodies, through your hair, touching the stones, enveloping the shapes, flapping through the fibers of your shirt, finding the salted pores of your skin. A whole world. The ocean, the Raft.

Michael Jones McKean is an artist and teacher based in the US and France. His work have been shown extensively throughout the world, and has received numerous awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship and fellowships at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Core Program; the International Studio and Curatorial Program; the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program’; the MacDowell Colony’; the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center; and the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, among many others.

He is currently an Associate Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University in the Sculpture + Extended Media Department; a Contributing Editor for Art Papers; and the Artist-in-Residence of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, the Museu de Leiria, and the Centro de Interpretação do Abrigo do Lagar Velho. His longform planetary sculpture, Twelve Earths, is slated to be completed in 2040.