Doris Adelaide Derby

Doris Derby at her home in Atlanta, 2017 [photo: Erin Jane Nelson; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

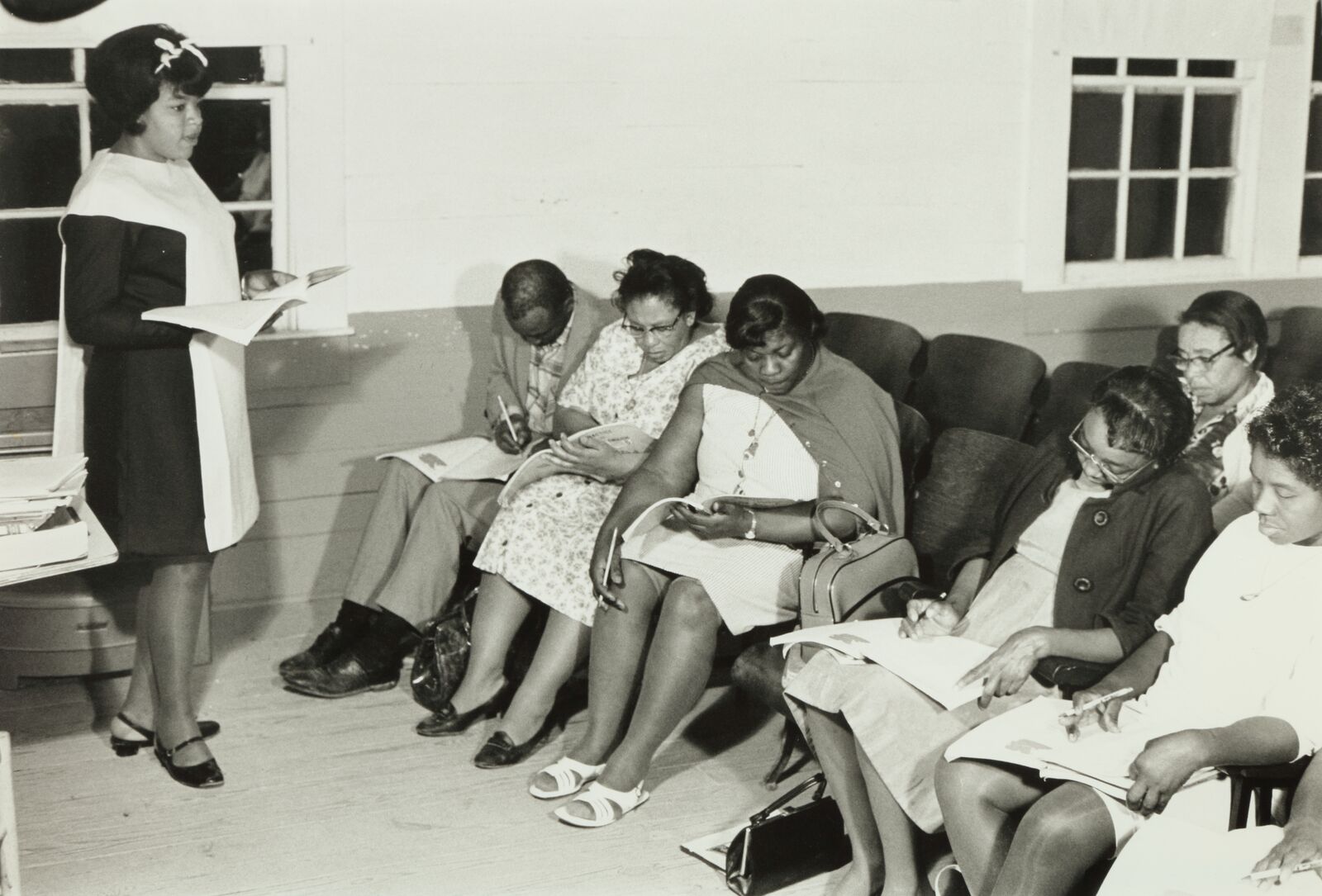

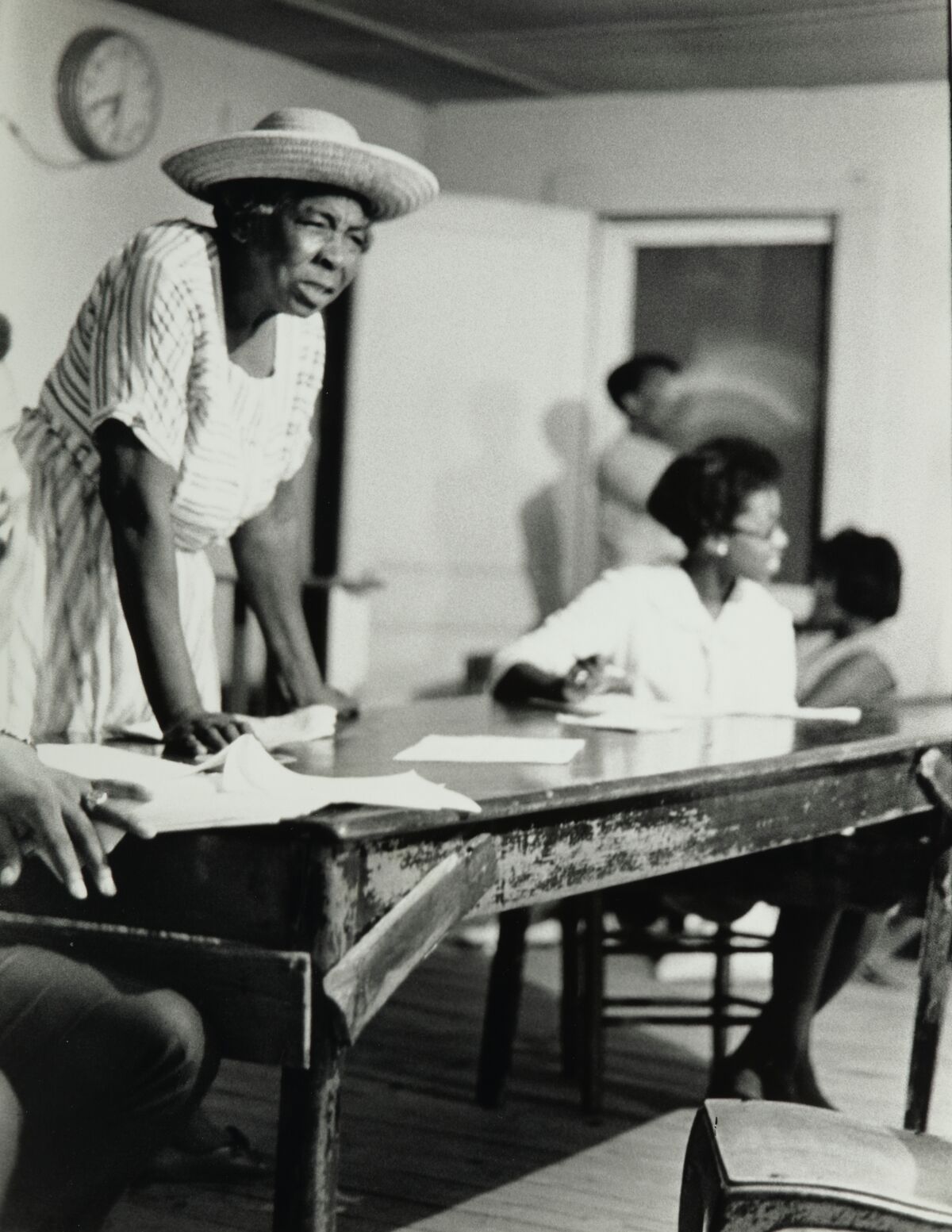

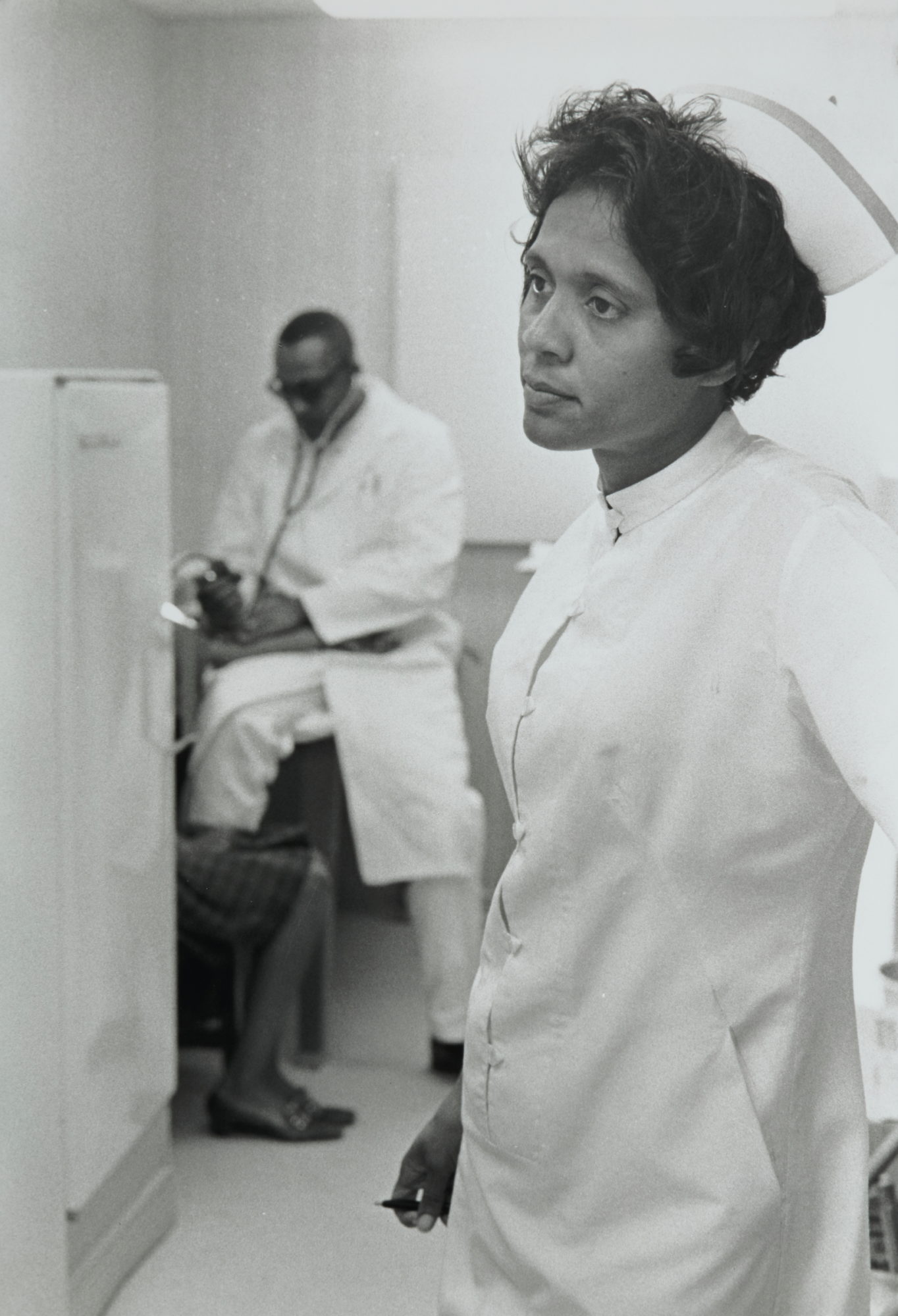

Bronx native and longtime Atlanta resident Dr. Doris A. Derby headed south from New York in the early 1960s. As a civil rights activist and educator, she worked as a Mississippi field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). As a photographer, Derby contributed to the Civil Rights Movement a vast visual record that powerfully documents the aesthetics and energy of the time. During her time in Mississippi, she co-founded the Free Southern Theater, which became a fixture in the burgeoning black theater movement that developed in tandem with the Civil Rights Movement. She taught literacy to adults to help empower communities to make use of their voting rights, and worked with early Head Start educational programs as they began to launch in majority black, rural schools.

Derby’s work as a photographer focuses on the women and children of the movement, and it makes visible the often unseen and unrecognized contributions women made to advancing communities small and large throughout the Southeast. What she has evolved since the 1960s is a practice encompassing not only education and photography, but also documentary film, mural art, writing, and group organizing—forming a professional path that might be considered an authentic, non-self-conscious precursor to what is now known as “social practice.” This fall, I spoke with Derby, retired Director of African American Student Services and Programs, and Adjunct Associate Professor of anthropology at Georgia State University, in her College Park home, where we discussed identity, purpose, and the movement—themes addressed in her works now on view at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, and throughout her multi-faceted oeuvre.

Doris Derby at her home in Atlanta, 2017 [photo: Erin Jane Nelson; courtesy of the artist]

Erin Jane Nelson: Can you describe how you originally became involved with [SNCC] in the south and why photography became such a big part of the work you did there?

Doris A. Derby: I originally became involved with SNCC during the 1960s, when I was an undergraduate. I belonged to the NAACP and the Student Christian Association, and was involved in student government at Hunter College. Student sit-ins and lunch-counter demonstrations were occurring in North Carolina, and other places. Students from different parts got together at Shaw University in North Carolina, to discuss inequality issues and the actions needed in relation to desegregating facilities and other actions. They started the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). As [northern students] in New York, we were aware of racial issues students all over were beginning to be concerned with. We wanted to support students in North Carolina, so we went on an integrated Freedom Ride to the Raleigh-Durham-Greensboro area to talk with students, black and white, about their goals and just learn about segregation firsthand. When we came back we agreed to support the students by raising money and by publicizing our experiences.

In the spring of 1962 I became an elementary school teacher. I took classes towards my Masters at night, but I was still in contact with Movement people. One of the young ladies who went with us to North Carolina, Peggy Dammond, decided to go to Albany, Georgia, to work with SNCC. I found out through her mother that she was in jail and was sick. I had been planning to go to Mexico, to visit a friend of mine, so I thought I would take a bus to Atlanta SNCC, travel by car to visit Peggy, and then go to Mexico, to see my friend.

I went to Atlanta, thinking I would only be there for a day or two, but it ended up being about a week before someone was traveling to Albany who I could accompany. During that time I got to learn what SNCC was doing, who was involved, and all of that. Eventually, I did go to Albany, Georgia. I was intending to see my friend, stay for three or four days, and learn a little bit about what was happening in Albany. Immediately after I arrived … we went to the movement office, where there was a lot of activity. Martin Luther King Jr., Andrew Young, Ralph Abernathy, [and] local Albany leaders—including Dr. [William G.] Anderson, were there. So too, were SNCC leaders—Charles Sherrod, Charles Jones, Penny Patch, Prathia Hall, and several others. And before I knew it, they were asking me, “Could you answer that phone? Can you type? Will you speak about our right to vote at a mass meeting tonight?”

EJN: They put you to work!

DAD: So, one or two days ended up being one or two weeks, and one or two weeks ended up being one or two months. And during that whole time there were many things that needed to be done. They needed people with my skills, and so that’s how I got involved with SNCC, really involved with SNCC—it was kind of an escalation of different experiences.

EJN: And that’s when you began teaching and really started taking photographs of civil rights workers?

DAD: I first started taking pictures after my father, who was a photographer for family activities, gave my sister and I both a Brownie camera, when we were in fifth or sixth grade. Then I always thought about visual images through photography. I left Albany, Georgia, in August of 1962, and went back to teaching. Before I left, Charles Sherrod, the head of SNCC workers there, asked me to raise money and get food, canned goods, clothing, and books for black families who lost their jobs due to Movement activities. I put on a big fundraiser at a major black church in New York City that spring. As a keynote speaker, we got Bob Moses, the catalyst for the statewide voter registration drive in Mississippi. Before he left he said to me, “We need to get you in Mississippi to work.” He said he had written a grant proposal to start an adult literacy project, and it was going to be based in Tougaloo College, outside of Jackson, Mississippi. However, I said no because I had some other plans. But in May I remember looking at the newspaper and the TV news the [day after] African American people in Birmingham were demonstrating, trying to register to vote, and calling for desegregation. Men, women, and children peacefully demonstrating, dressed up with their Sunday best, and the police rewarded them with billy clubs, fire hoses, and dogs. German shepherd dogs.

EJN: That was at Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham?

DAD: Yes. I thought it was such a horrible thing to do, and I decided that if there were people willing to take such a stand and be attacked, the least I could do would be to use my skills and my experiences to work in the literacy project in Mississippi. And so, I was hired as a SNCC field secretary in Jackson.

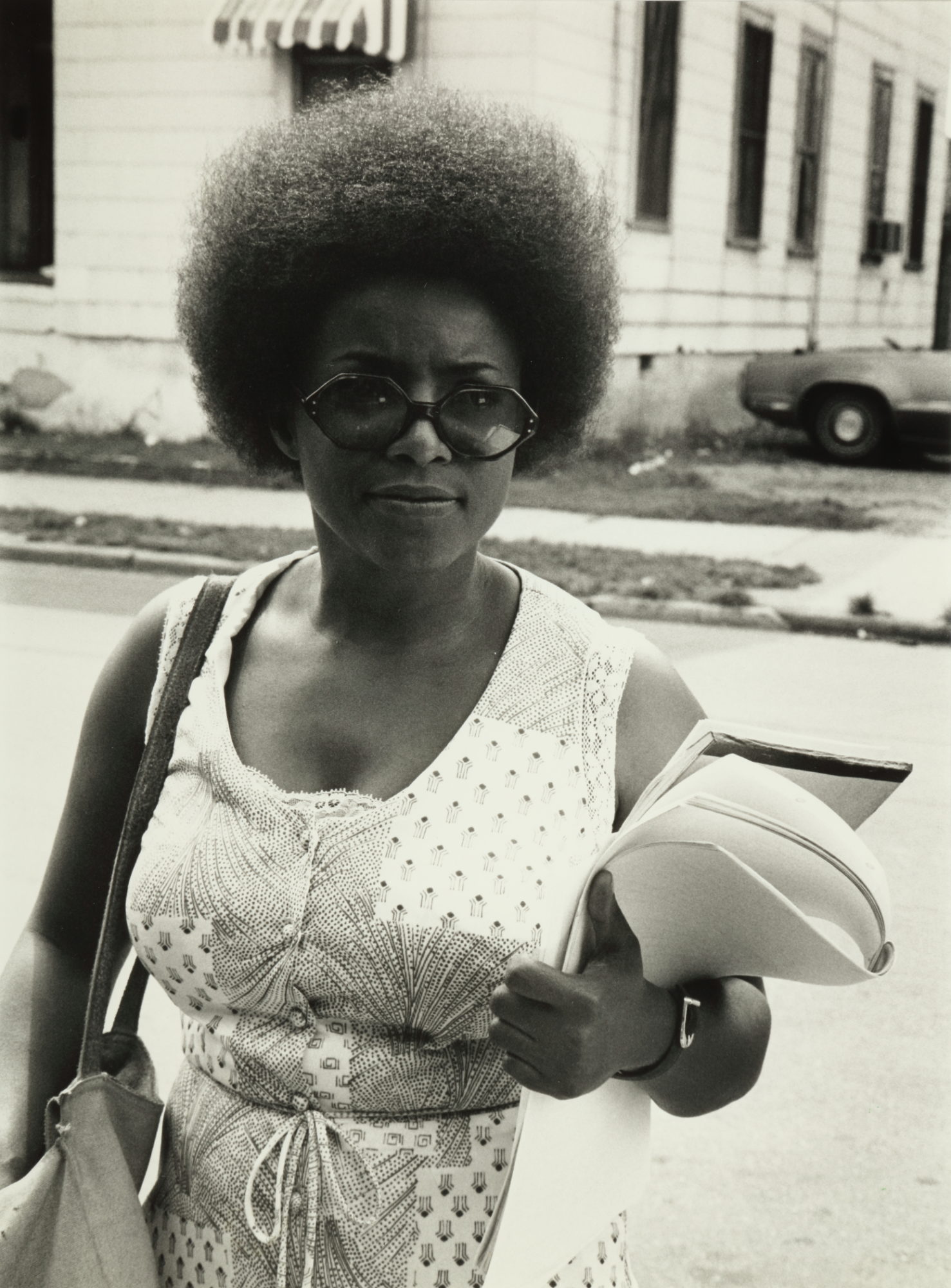

Doris Derby, “Nausead Stewart, Civil Rights Attorney,” 1970, gelatin silver print [courtesy of the artist]

“Not all aspects of our lives are about the injustice.”

EJN: Is there a particular photograph you saw or took, or an event that you documented during your time in Mississippi, that has stood out for you as particularly impactful or valuable to you?

DAD: Well, that’s kind of hard to boil down to one image. I like taking photographs of children. I always say that with all of these things that are going on—that have gone on, in terms of social justice, issues of segregation and equal rights, our struggle, and the Civil Rights Movement—I always say “the children are watching.” So I have many photographs of children. Their faces are very important to me. I’d also say that photographing the farmers, both men and women, produced images that people don’t [often] see—they don’t know about the life of farmers, and particularly black farmers. The struggle they have to go through, you can see it in their faces. You can see the emotion of strength, determination and joy, as well as that struggle and hard work out there in the fields. One wonders how many people who are growing up in the city, or how many people who are sitting in offices, would be able to sustain that kind of life. Photos remember forgotten generations. Photographs of leaders like Fannie Lou Hamer or Lawrence Guyot—these are people whose images as grass-roots leaders stand out in my mind. And then, certainly, women in the handcraft and vegetable co-ops, and just women at home with their hard work—[those] are groups of images that are very important.

EJN: We’ve talked a little bit before about your interest in Roy DeCarava’s photographs—can you describe what drew you to his work, and share any other artistic influences that you were looking at early on in your artistic and activist career?

DAD: I like Roy DeCarava’s photographs— I knew him and was very familiar with his work. He was a role model to me, because he documented the lives of black people in all aspects. The viewpoint is positive regardless of what the person is doing. It’s not a stereotype; it’s just a positive image of what is. It shows the person in various dimensions that are humane. He’s got couples getting married and enjoying themselves celebrating, he’s got children; he’s got people that are dressed up or not dressed up. You know, he especially depicts people in the city—in New York City—and that was impressive to me because I was brought up in New York, and I have seen all those positive aspects of black life, growing up. I was always disappointed that, in mainstream books, movies, paintings, performing and visual arts … we were not depicted like that. So that was an inspiration to me to depict positive images of black people wherever I was, wherever they were or are.

In New York I used see African American visual artists, painters, and illustrators—Ernest Crichlow, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Henry O. Tanner—so many positive black artists [who] had been painting for years. Even though they didn’t make much money, they were able to still stay true to their calling. There was also George Wilson … AfriCOBRA … Jeff Donaldson, and so many others. The historically black colleges and universities that had art departments cherished black images and had collections of African American art— they were an influence to me.

EJN: So, at the same time as the Civil Rights Movement, the women’s rights movement was happening, and a lot of your photographs deal with the women of the Civil Rights Movement, who were not as visible as the men. Did you consider yourself also part of the women’s movement? Were you interested in thinking of yourself as a feminist artist, or were you just a woman making art?

DAD: As a woman, as a young girl, [when] I started out my major concern and mission was to make sure that African American people—our life, our history, our culture— is archived, is available, is presentable, and is inspirational to African American people, to people of African descent, and to the entire world. We must remember that a lot of what we have done has been out there, but who generated this work, who inspired this work? We have never gotten our proper acknowledgment for the cultural contributions that we have given to the world, that have come from Africa, from African descendants in the new world. We have not been acknowledged as the progenitors of the work in the arts, in science, in history, in all categories of life. So, my main concern has been documenting what we are doing, in the past, the present, and the future. And I have done that as a black woman. Now, granted, this world has been a man’s world—predominantly a white man’s world, but still a man’s world. Women in the black community have done so much, but when the media picks it up or those in control of textbooks pick it up, they do not include what we do not only as black people, but as women. So, I would not say that I have been a “feminist”—I have been working on behalf of humanity, of black men and women, to give us our proper dues, to acknowledge our contribution to America and to the world. Back in the day, Alice Walker said that was a “womanist” perspective. So I would say, if that’s the case, if it has to be one thing or the other, it would be a womanist perspective. I’m not in that feminist box as people try to narrow it down, but I do see that the roles of women need to be revealed within the perspective of the African American contribution, the African descendants’ contribution to the world.

EJN: “Womanist” being more about equality and humanity rather than one specific kind of side of an argument.

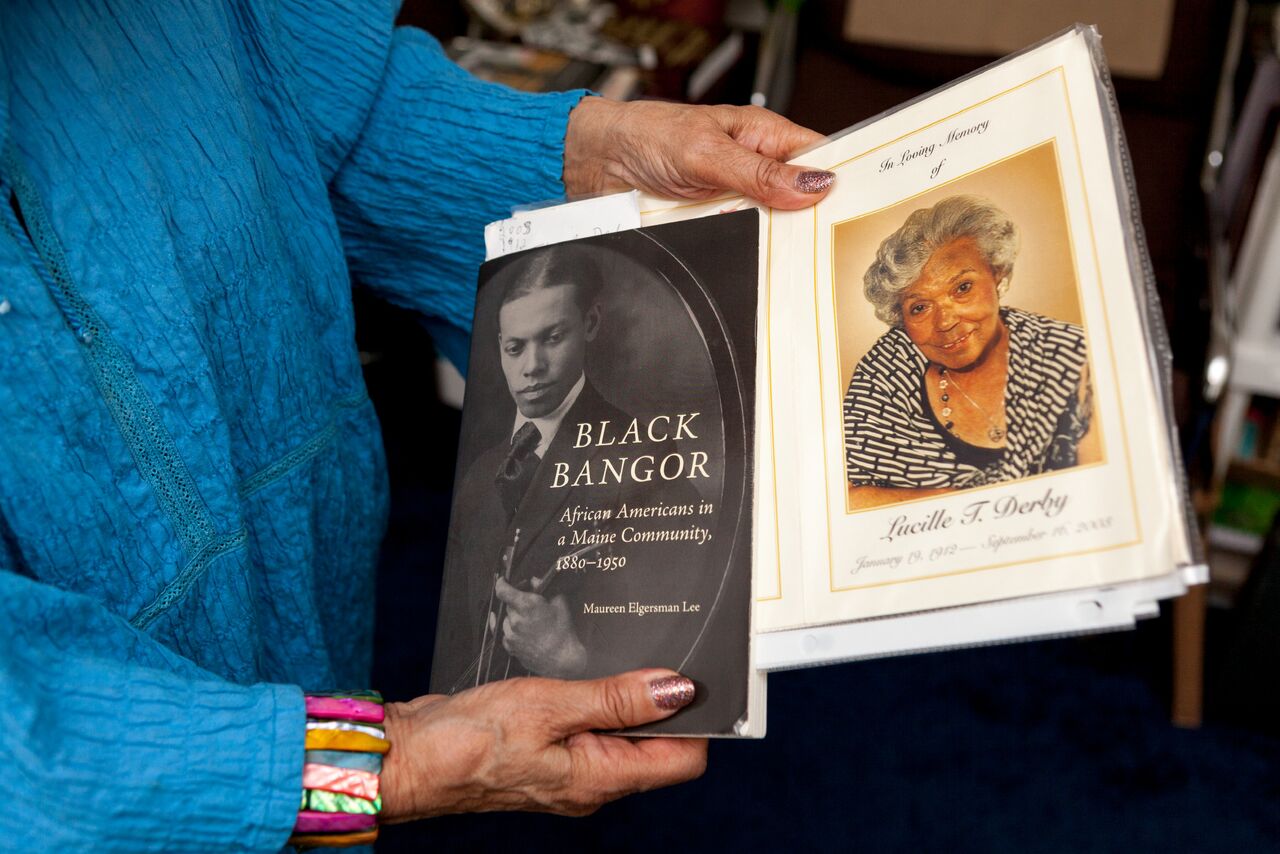

DAD: What I saw, as an individual growing up, was my family, friends, and extended family that contributed to our community, and continuity on Earth. I know that it was both men and women, in the families that, to me, made the greatest impact. My brave and industrious grandparents! My grandmother and her oldest son, my uncle Alonzo, were founding members of the NAACP in Bangor, Maine, in 1920. So, it was men and women doing things in the black community—we had to work together, struggle together.

Image courtesy of Doris Derby and the High Museum of Art

EJN: Since your work with SNCC began in the 60s, you’ve started theater companies, you’ve written children’s books, taught at all age levels, worked in administration at Georgia State University, worked on documentary films, and I’m sure so much more that I’m not mentioning here.

DAD: And still doing it.

EJN: And still doing it, constantly. How do all these pursuits relate, for you? To me it reads almost like a precursor to what is now described in the MFA industrial complex as “social practice” artwork. Do you see all these pursuits as parts of a continuous creative practice in that way?

DAD: These pursuits are all related. Their formation and foundation is something that started when I was in elementary school. I’m unfamiliar with the term or concept of “social practice art,” but to me it is a continuous form of creative expression in my life; it’s been something that I have done since I realized in elementary school that we needed to see our cultural and historical images in books and films, because they’re not there. We needed to put them there, as the way we see them, as a people—not in the way somebody else wants to see them, to influence us or to negate us or our contribution to America and to the world. Inasmuch as social practice relates to revealing and righting injustice, yes. But not all aspects of our life are about the injustices—I photograph our daily living, our struggles, our relations within ourselves, our own communities, our families, that are humane and that are happy. And we savor the moments of humanity, our humanness and our God-given life and experiences. That’s what my work reflects.