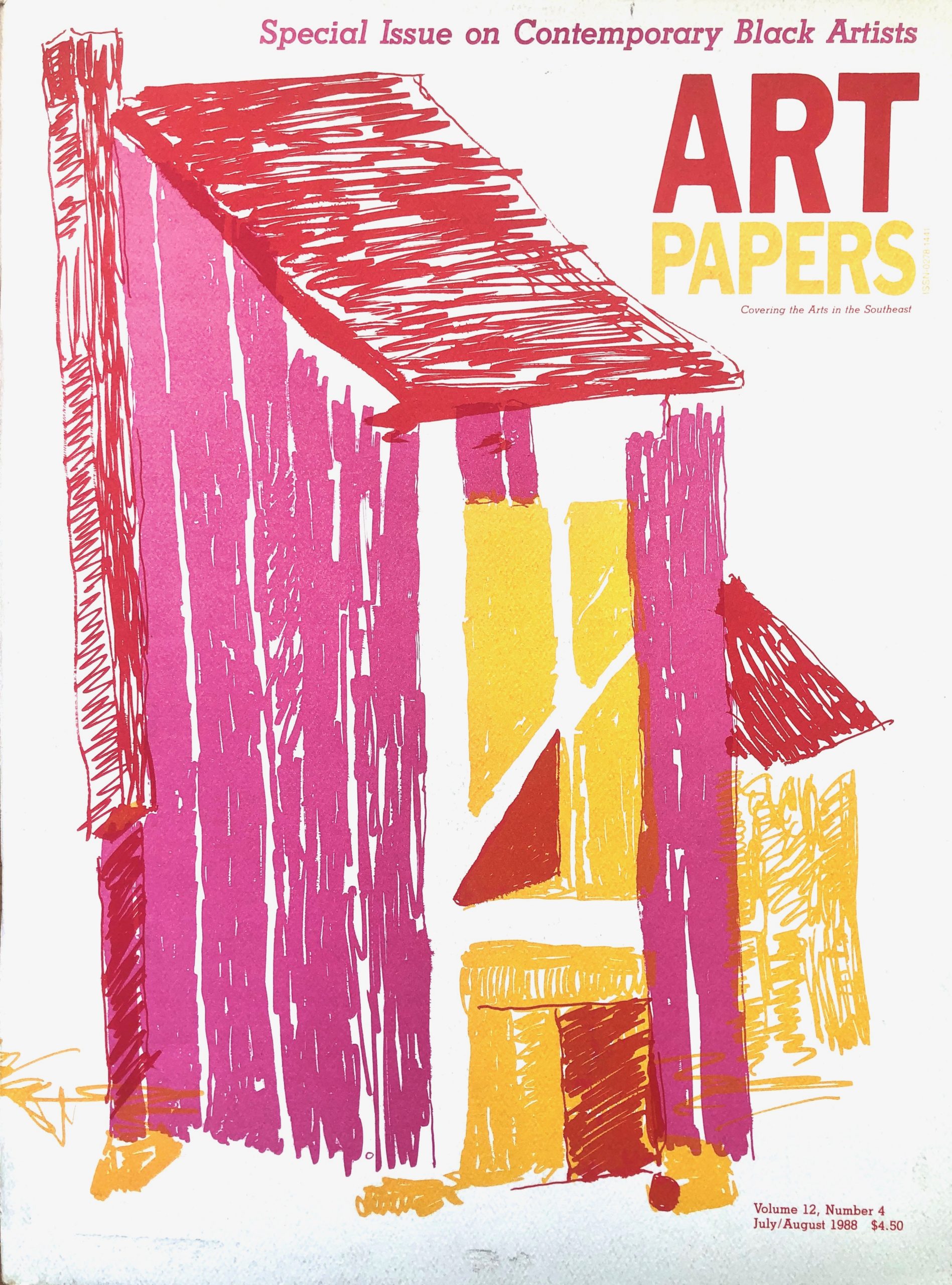

1988 Special Issue on Contemporary Black Artists

In 1988, ART PAPERS was in its 12th year. Mildred Thompson was an associate editor, and the editorial direction of the magazine was already firmly rooted in intersectional art criticism with an eye on race and class. These commitments manifested in the July/August 1988 Special Issue on Contemporary Black Artists.

The issue recently sold out in print, so we have made several of its features available in this online dossier. Texts are reproduced as they appeared in 1988, although without Charlie Reidy’s signature typography from that era of ART PAPERS. It may not surprise readers that many of the issue’s essays and features feel as if they were written yesterday. And of course, others are quite obviously from the late 1980s. We hope these archival texts provide history and context to current conversations, as well as an insightful glimpse into the thoughts of our predecessors from more than three decades ago.

Mildred Thompson’s introduction to the issue—which we consider essential reading—is below.

The Black artists presented in this issue are but a few of the world’s working artists, the “creative souls,” often working alone and isolated, who manage to develop, explore and expand their means of self-expression though they may or may not receive rewards from the established order. We ask what keeps them going under all the evident hardships. Why do Black artists, in particular, continue working in an environment that has and continues to ignore and reject their existence and their work? They continue, perhaps, because they have at one point or another experienced the rare thrill of having come in contact with sources greater than themselves. Perhaps they have been able to transcend the limitations of success and failure. During the process, many artists have been able to reach higher states of consciousness, similar to those of the mystics. In cultures where artists are seen as visionaries, they are highly respected for their abilities to see beyond known realities. Yet we are here and now, our time and location are real factors that influence any creative process.

Of time there is much interest: everyone is talking about the very strange times in which we live. As the century is speeding toward its end, we are frightfully aware of the many transformations that will occur in a time of such rapid and often violent transition. Industrialism is dying and we are embracing the new technological era for its promises, though it also threatens our very existence. We see standards change as old values shift. We are shocked to have our myths revealed as such, even as new myths form to replace them. We mourn for our long loved traditions as they vanish. Looking forward, we can more readily look back. We can now, we think, evaluate and analyze the century that is ending. We can understand the art revolution that ushered in the original avant garde and can accept without contempt all of the movements that have followed throughout the century. We expect revolt. We see that the art revolution is not dead: new methods of producing art unfold at such speed that we cannot create a language fast enough to describe them.

Of location we may say that there are places on earth where creativity flourishes and there are others where any act of creativity and any production of art is thwarted—in either case due to the political and social circumstances. This has caused and causes many artists to live the lives of wanderers, in constant search for “the location,” where growth and personal expression are supported and encouraged. We are focusing at the present on Black artists, most of them living and working in the United States. These artists function in a peculiar environment, whose foundations were laid when Calvin Coolidge pronounced that “The business of America is business.” Everything that is not business scrambles for a place as close to business as possible. Sales records are used to define success and failure, standards of art are set by what was sold and what was not, by what will and will not sell. The artist like everyone else is affected by the system, but the artist, whose function is not central, is kept perplexed, anxious, and confused. The “creative soul” growing up here is made to understand at a very early age that s/he is different, and that her/his interests are not recognized as vital and are not encouraged. By the time of specialized study, one is forced to choose “commercial” art (no freedom to create, but the lure of a steady paycheck) or “fine art” (freedom to create, with warnings of destitution). No matter which choice is made, forever after the artist doubts having made the right choice. The fine artist is so programmed that when his or her work actually sells, s/he becomes doubtful of the validity of the work. If there are no sales, then the artist is forced to question the validity of the self. The Black artist, under the burden of all of this, has the additional burden of America’s history of racism and discrimination and may question the validity of making art in such a society. The Black artist is often, in galleries and museums, included out. Buyers and collectors, Black or White, are rare and difficult to contact. The Black artist is forced into a double sense of poverty. The non-salaried artist is often seen as a peddler/beggar, an unemployable dreamer at best. Racism, indifference, and ignorance do not pause for art. We have not been trained to wish for art as we have been told to wish for foreign cars. The Black artist here, in these times, is in a dilemma, dictated to from all corners of the social and political arena. S/he may find acceptance neither here nor there.

The artists you will meet in this issue are Black, a racial identification. It may not always be clear what defines Black art: is it art made by African or African-American artists? Is Black art that which is representational and portrays Black people? What of a Black artist whose work is non-objective, abstract? What and who defines Black art and the Black artist? Does not every act of creation denote something of the race, creed, and sex of its creator? Is it not true that “Every man beareth the stamp of the whole human condition?” The works and words of the artists and writers featured here may help to answer these questions.

— Mildred Thompson, ART PAPERS July/August 1988

Share:

The New Exclusionism

Catchwords like “diversity,” “transculturalism,” “pluralism” cause my antennae to go up, and warning bells of skepticism to go off in my head. Not about these ideas per se, you understand, but about the way they are being implemented in our free-enterprise society in the 1980’s.

Where is the Art World Left?

Where is the artworld “Left” in the age of “trickle-down,” homelessness, the rise of the Aryan Nation and corporate art coma: a dehumanization of art and artist into a common denominator of profit?

Interview: David Hammons

“I can’t stand art actually. I’ve never, ever liked art, ever.”

Marketing Afro-American Artists

Afro-American artists will never get their fair share of the market until and unless white males, who control almost all the major cultural and academic institutions in our society, finally accept the well documented fact that “Western Civilization” would not exist were it not for the contributions of most of the human beings in the world.

In Memoriam: Romare Bearden (1914-1988)

David C. Driskell pays homage to Romare Bearden.