Derrick Adams: Beyond Spectacle

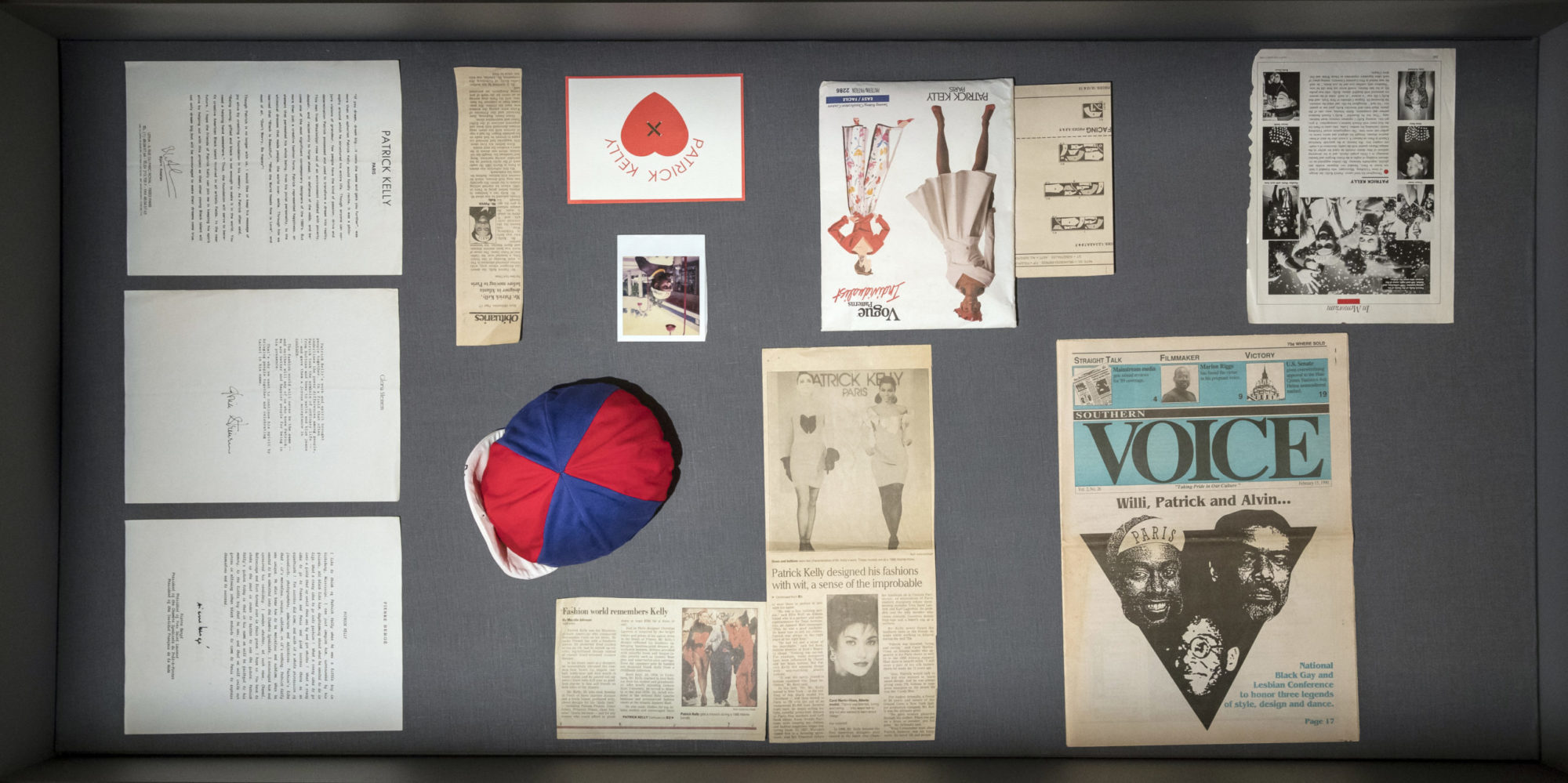

Derrick Adams, “Patrick Kelly, The Journey,” installation view [courtesy of SCAD]

Share:

Patrick Kelly, The Journey at SCAD FASH is currently closed until further notice, thanks to the threat of COVID-19. Before the exhibition opened, briefly, to the public, I was able to sit with Brooklyn-based multidisciplinary artist Derrick Adams to discuss the creation of this body of work meant to exalt the global impact of fashion designer Patrick Kelly (1954–1990). Kelly was born in Vicksburg, MS, and gained fame for being the first American admitted to the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode (French Syndicate of Ready-to-Wear for Dressmakers and Fashion Designers). He was known for his size-inclusive designs, his energetic runway shows, and his iconic denim overalls.

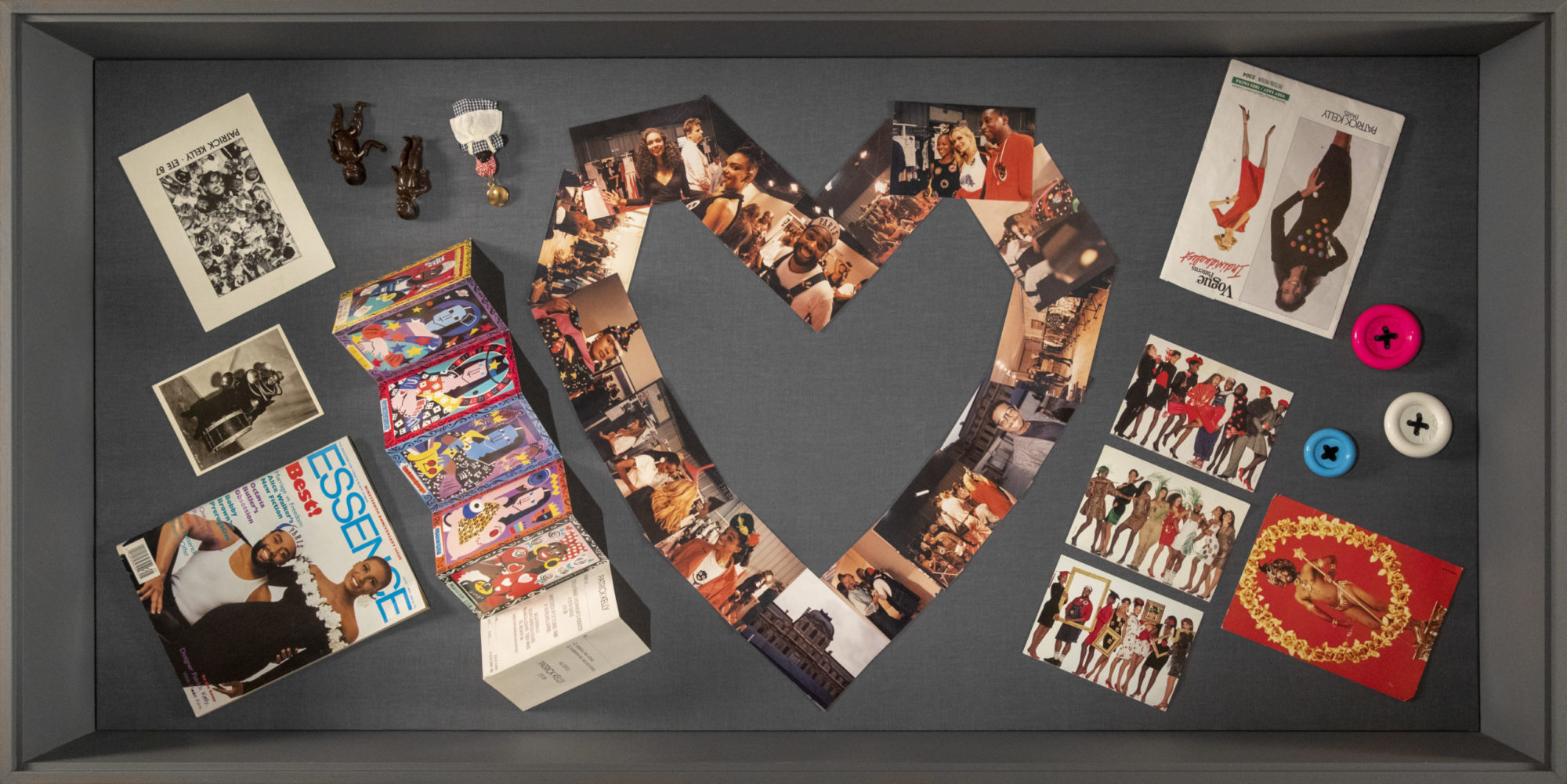

Having first appeared in 2017 at New York’s Countee Cullen Library, Adams’ works at SCAD FASH are supplemented by ephemera that links Kelly to the city of Atlanta. The original body of work stemmed from extensive research in Kelly’s archive, which is housed at the Schomburg Center for Research and Black Culture. Although this new iteration of the exhibition presents a fuller picture of that life, Adams reminds us that Kelly’s narrative should not distract viewers from the artworks. Adams created a series encompassing collage and sculpture that emphasize Kelly’s ingenious forms, patterns, and embellishments to portray Kelly as a master designer, beyond the spectacle of his fascinating life.

TK Smith: This body of work first appeared in a public library. Did knowing that [fact] change how you created the work, the concepts of the work, or how you expected people to interact with the work?

Derrick Adams: No, I knew it would be in a library. The Studio Museum in Harlem is closed, and this was the first inHarlem show. inHarlem is the satellite program that puts on exhibitions in different public locations as a substitute for the museum [space, which is] being rebuilt. It became an option to show it in the Schomburg research library, but they were undergoing construction. I was really interested in [the work] being in a particular context, so when the Countee Cullen Library, next door, was available, that was it. At the public library anybody can go and hang out, charge their phone. A lot of younger people are coming to use the public library because of that accessibility. You know, some artists [want] their work being presented in a very particular way: pristine, maybe a white cube or whatever. I knew that my work was going to end up in a [white cube]. I think when you have something to say, [the work] has many lives, and [the library] was the beginning.

I felt like having it there would [create] the best historical context for looking at where the work started and where it’s gone since then. I learned, after it first opened, that [A’Lelia daughter of Madam C.J.] Walker owned the house that is now the Countee Cullen Library. I thought, that’s interesting—this whole idea of beauty, the beauty aesthetic, fashion, and [the daughter of] this woman who is an icon. [Madam C.J. Walker was the] beginning of this idea of consumer culture …. A lot of times people try to control certain spaces and certain [variables that their] work can be in conversation with. I think that it was a perfect storm that it ended up in that space, attached to that history. All of those things gave it more impact, because it was not presented just as a commercial exhibition.

Derrick Adams, “Patrick Kelly, The Journey,” installation view, 2020 [courtesy of SCAD]

TKS: What is your role, as an artist, in the preservation of Black history and culture?

DA: People are looking for [artists] to make works that are enforcing the obvious [Black] narratives that people fear are going to be lost. In all actuality they won’t ever be lost because the obvious narratives are the narratives being perpetuated—Black people dealing with this oppressive structure. [Some artists may feel] we have a certain obligation to speak for everyone. I think [that it’s] important for artists to feel that way, if they feel that way, but I think that it should be on a case-by-case basis.

I think that artists who want to speak as an individual—be it [with regard to] race or gender, their relationships with their families—should do that, because that is what, for me, determines what it means to be contemporary, to be a part of contemporary culture. The contemporary culture is about showing various aspects of who we are. Having people understand us [as being] from regions—the Caribbean, African continent, the South, the North—places with cultural distinctions.

TKS: What stories and truths are you intentionally passing on through your homage to Kelly’s work?

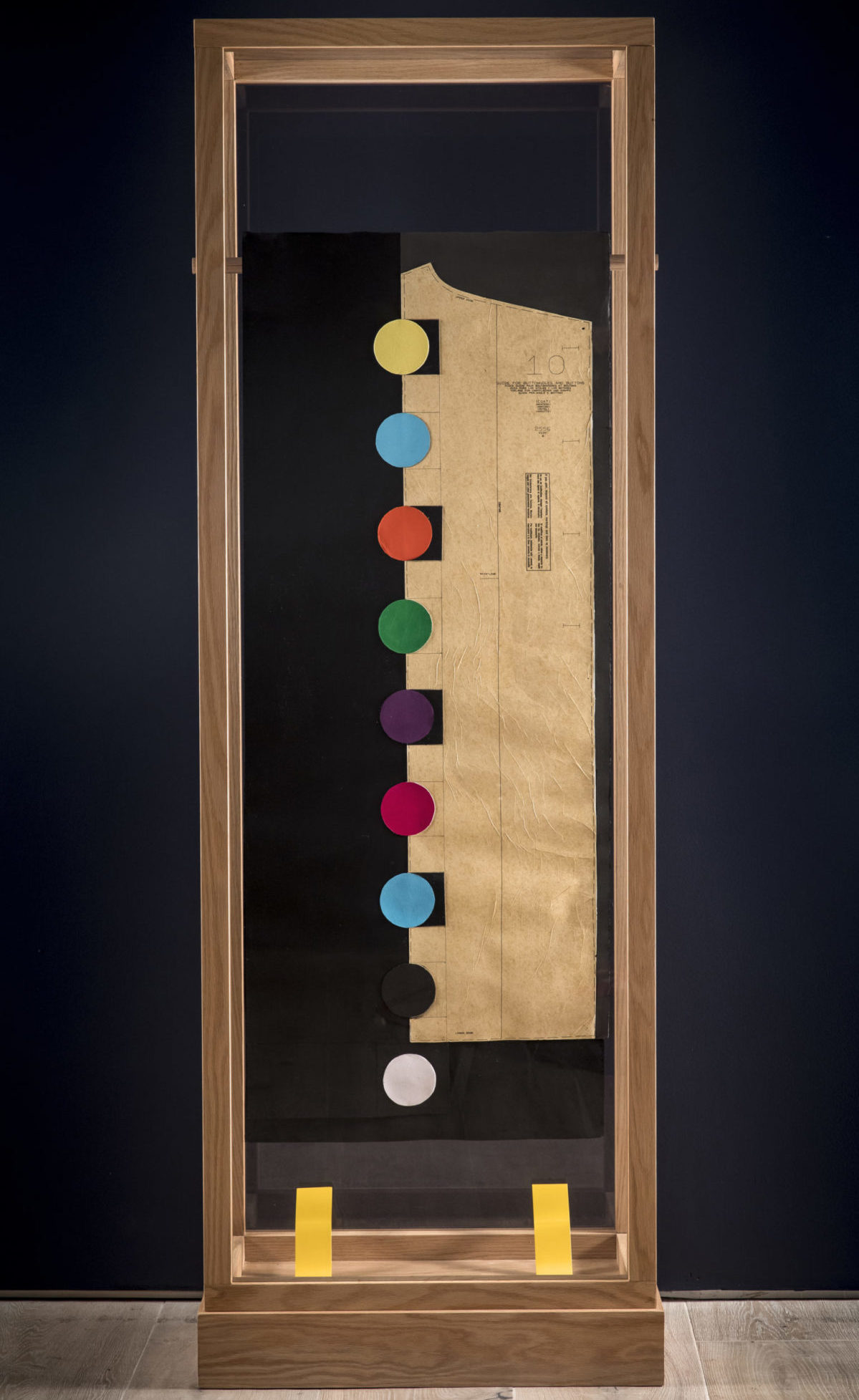

DA: Materiality. Patrick was from Mississippi. When you hear him talk, when you look at his work, when you see some of the objects he used, [each of those things is] from a very particular place. As a Northerner, a black person in the North, a lot of things that were his legacy or from his influence were not mine. To force it into my narrative is not how I work. I try to figure out what about [Kelly’s] work, his legacy, and his practice … I’m connected to, and how that can be part of a genuine approach to my making art.

TKS: Can I ask what some of those things are?

DA: The interest he has in color. The interest he has in talking about Black women, the influence [of Black women, and] the way that he was interested in creating spaces for those types of women. I think about those things when I’m thinking about art. I’m thinking about the person who may not be in the conversation, may not be at the table, and how to bring [that person] into the conversation by acknowledging them through [my] approach. You can acknowledge them by your arrangement of color, you can acknowledge them by the way you create openings for them to participate. Be aware of them as a source of inspiration, [not as] a person you have to educate. [Understand] that they bring a certain level of experience that [you] don’t have and how that [experience] can become fuel for challenging you and challenging me as an artist.

Derrick Adams, “Patrick Kelly, The Journey,” 2020 [courtesy of SCAD]

Derrick Adams, “Patrick Kelly, The Journey,” 2020 [courtesy of SCAD]

TKS: What is personal for you? In the same way that Patrick Kelly was creating work referencing his personal experiences and influences, what in the archive did you have a personal experience or connection with?

DA: What is personal for me as an artist was recognizing the ability and freedom of artists who are not Black to occupy a space of formal execution and intellectualism that were not necessarily allowed to us.

I teach at Brooklyn College, and one of the challenges for a lot of students of color is how to take something that’s personal, experience that’s personal, and to formalize it in a way that can be juxtaposed to something else that’s formally and aesthetically pleasing. I tell my students all the time [that the work] can be about anything, but if you’re making a painting and it’s not a good painting, it can’t be in a painting show. If one of your goals is to be in a museum or gallery show, and your work is about trauma, it still has to look good. It still has to be visually interesting regardless of what it’s about, to sustain the space. If it’s a sculpture that’s based on some personal issues or personal experiences, it still has to be a good sculpture. When you think about it, as an artist, if you go to art school, you want to be looked at as a good artist. [Being a good artist isn’t] usually based on the narrative, as much as it is based on the construction. The narrative is only going to add more layers to whatever you’re looking at to heighten the aesthetic principles of it.

TKS: So, you’re talking about craft, the craft of making an art object?

DA: Translating the narrative into an object, which doesn’t have to be perfection. Craft is about mastering something. [I’m talking] about being able to capture the audience in [such] a way that the object brings them to the narrative, not the narrative dominating the object.

TKS: Is that why you decided to translate the archive more abstractly?

DA: The archive was very fragmented. It wasn’t linear at all. [There were] letters, postcards, photographs from a birthday party. [There] was a letter from Maya Angelou to the publisher, and rough sketches of his concepts for his fashion. There wasn’t a lot of linear narrative or heavy insight into who he was as a person, other than just what was laying around in his house, probably.

I think [that] when people donate their archive, if they prepare their archive, it’s going to be more dynamic. I think [that] whoever donated [this archive], they were thinking about what they thought people should know about Patrick. This archive, I don’t know if it was his personal arrangement. So, all I could do is kind of fill in the blanks of what I imagine would be important. What I think is missing in art, when you think about an artist of color and their work, [is that] people rarely talk about the construction of things or the formal structure, or the craftsmanship; they usually talk about what the work is about.

Derrick Adams, “Patrick Kelly, The Journey,” installation view, 2020 [courtesy of SCAD]

TKS: So what is the narrative, if any, that you hope viewers walk away [with] or experience from Kelly’s life?

DA: He was a conceptualist. I think that he was [also] a formalist, in a lot of ways. I think that if he [had been] born in a time, other than the time he was born in, and existed in fashion, he would probably have [had] a lot more liberties. He probably would have felt more liberty [in] being expressive in a particular way, unlike the way he was presenting his work. I think that he was trying to fill a space of neglect of people seeing the Black community, seeing [Black] models in the world.

Now, when I think about [Kelly], he wanted to be in the mainstream. I don’t care about that as an artist. I feel that we are already in the mainstream. I feel like whatever we do is at the top, because it’s not being seen as a means. I don’t need to have a corporation attached to me or backing me to make me feel legitimate. I think that [he was] of a time [wherein] you wanted to be looked at [in a way] comparable to other people [working in] that genre. I don’t think like that. I don’t feel that I’m missing anything by not being part of the establishment.

TKS: I was thinking of the framework of rap music. One of the most beautiful and powerful things about rap music is this oral tradition. It takes samples from older songs and older knowledge. A younger rapper will quote an older rapper to retranslate the same knowledge, whatever knowledge that might be, however problematic it might be. I was thinking of your interrogating this archive in a similar way.

DA: When you think about artists of a previous generation, Fred Wilson or even David Hammons, for them to be in [conversation] with another artist that they looked up to [meant] that artist was [presumably] not another artist from the same cultural background. For me, that’s not a challenge. I can make work in conversation with Patrick Kelly, I can make work in conversation with David Hammons, I can make work in conversation with other artists [whom] I’m inspired by [who] may be similar in content and form. That’s a privilege that I have that I think did not exist for those artists. I want to bring light to those artists, like Patrick, who are not only radical in dealing with social and political issues, but also thinkers. They know how to articulate design, to articulate color and form.

Derrick Adams, “Patrick Kelly, The Journey,” installation view, 2020 [courtesy of SCAD]

Derrick Adams, “Patrick Kelly, The Journey,” installation view, 2020 [courtesy of SCAD]

TKS: Would you use the word honor when you talk about this body of work?

DA: I would say exaltation; I would say that. I am exalting him in a way that people were not, even people [who] knew him. I think that people would [assume], if I did something with Patrick Kelly, I would do the Mammy characters or things that are just identifiable iconography. I went a different route, because people don’t think about him [in the context of] his work. Even when I say I’m doing a show that’s inspired by Patrick Kelly, they probably came here thinking they were going to see some of the Negro memorabilia that he would collect, that he felt strongly about, but he was from Mississippi and that’s a place where you can still go to places and see those things in the stores. I’m from Baltimore. No one [there] has [things like] that. Growing up, I’d never seen that [stuff] before in anybody’s house. I know artists from down South; they’ve incorporated that into their work. It becomes a part of the cultural landscape, of that history and that time. I think that’s important for artists, like rappers. When you hear a rapper from LA, they’re different from a rapper from New York. I’m not trying to rep like I’m from LA, I’m repping … where I’m from. … I’m more interested in talking about aspects that I connect with within this work, as it relates to my work and how I make it.

TKS: That’s beautiful, and that makes this new body of work more yours?

DA: Yes. It’s named Patrick Kelly, The Journey because it’s really talking about where he came from leading up to where I am. His journey is basically attached to my presenting him or re-presenting him in a new context, me speaking on him in a way that’s about aesthetic and intellectualism. Not that other things [about him or his work] weren’t important, but it’s something that is now going to be a part of the narrative when they’re talking about him. I’m pushing that into the narrative—the discourse about Patrick—forcing people to write about it so that [history] can never be unwritten, so when people talk about him they have to talk about that, too.

TK Smith is a writer, critic, and curator. He is currently a Tina Dunkley Curatorial Fellow in American Art at the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum. Originally from Iowa, Smith recently relocated to Atlanta from St. Louis, MO, where he received his MA in American Studies from Saint Louis University.