Claudia Peña Salinas: Seeing Sites Without Sightseeing

Claudia Peña Salinas, Kan, 2020, bronze, wood, and neon [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

Share:

Claudia Peña Salinas takes stock of how some of the most visited archeological and spiritual sites in Mexico endure tourism for generations, yet still provide eternal inspiration. At locations such as cenotes, natural pits often used in Mayan rituals, water intended to reflect light onto sacred structures now also illuminates passels of sightseers. Peña Salinas’ capacious installations, sculptures, and prints offer negative space for viewers to navigate archaeological sites and cultural mythologies. What emerges from her practice are not only immaculate forms but encounters that disrupt Western temporality and visual consumption.

Her recent solo show Itzkan, presented by PROXYCO and Embajada in New York [October 22–December 23, 2020], took its name from itz, meaning magic, and kan, meaning serpent. Suturing her work with synergy, Peña Salinas does not reference a magical serpent alone but also a serpentine power that weaves through generations of folklore, spirituality, and colonization. In advance of her exhibition Memory Palace [January 7–March 3, 2021], at the High Line, Peña Salinas and I spoke about how her refracted photographic prints and pyramidal installations mimic touristic encounters to underscore how Indigenous knowledge reveals itself amid the obfuscation of colonialism.

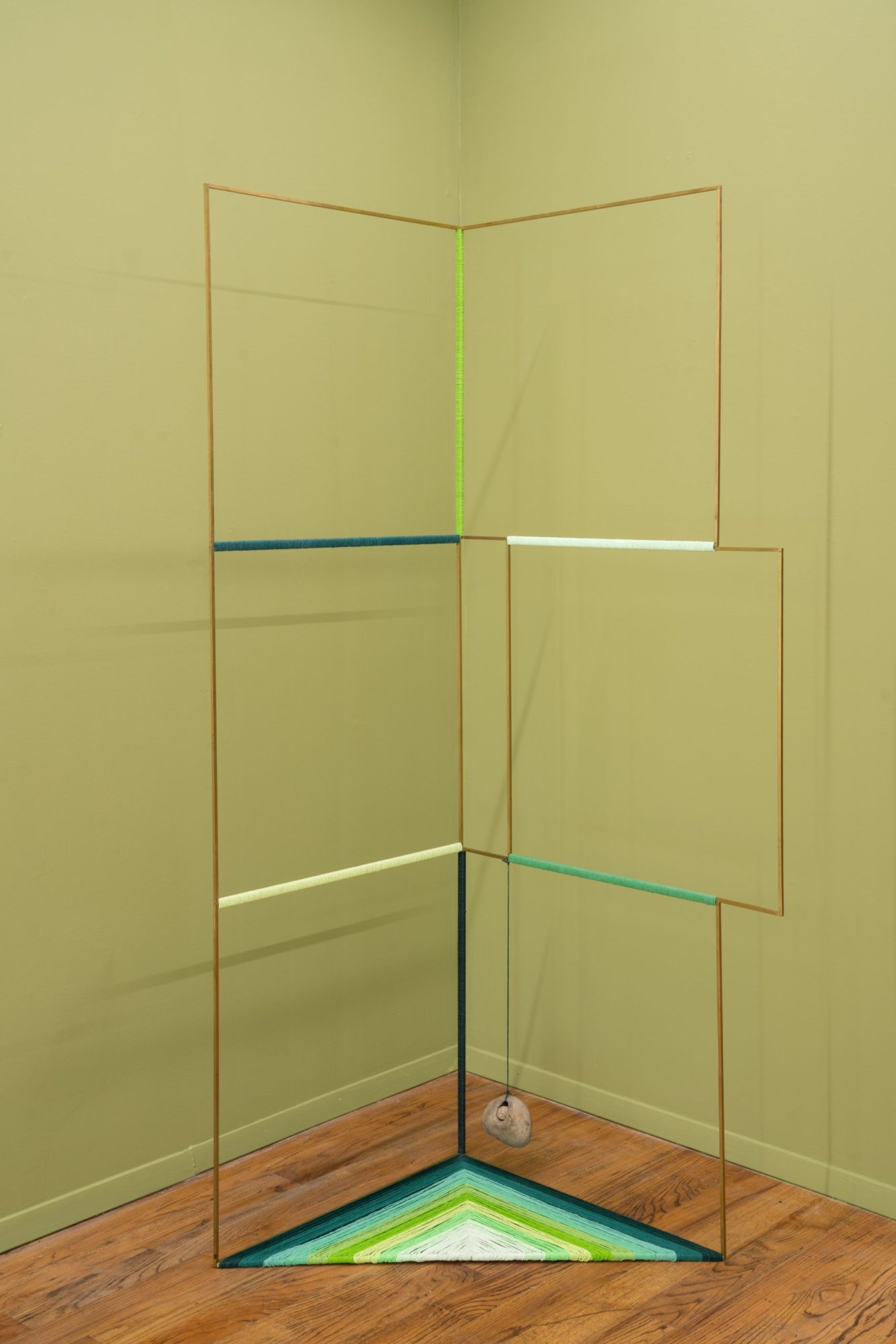

Claudia Peña Salinas, Tunich, 2020, brass, dyed thread, ceramic, and river stones, 24 x 53.5 x 24 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

Claudia Peña Salinas, Tunich, 2020, brass, dyed thread, ceramic, and river stones, 24 x 53.5 x 24 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

Jack Radley: Your work dialogues with the architecture, stories, and myths of Mexico, yet you present it outside of Mexico frequently—in the US, Tokyo, and other places. How do you approach the presentation differently in these locales? How do you think this affects the reading of the work?

Claudia Peña Salinas: It’s always important for me to deal with the site and the locale, so I will always try to research it. I will go take walks if possible, read about the area. For example in the two exhibitions that I had—one was at Galería CURRO in Guadalajara—I went there for a month, and one of the main sculptures had four objects. The intention was to source these four objects from Guadalajara, so for that month I was walking around, looking for these four objects. And you know, it’s a very intuitive kind of process. I don’t know what, necessarily, the objects are going to look like. They ended up being four obsidian shapes, from different sources and different areas in these walks. And then, when I did the show in The Club gallery in Tokyo, I went to the mountains of Nagano—about two hours away from Tokyo. I was going into a lot of waterfall sites, and I found the four rocks that would become part of the exhibition.

JR: How did you know they were the rocks?

CPS: I didn’t. I had, like, 50 rocks, and in the end the problem was, like, what do I do with these rocks that don’t make it into the exhibition? I felt a sort of responsibility of having taken them from a site. Would I just leave them in the studio or return them to the waterfall? I did take them back and put them back in the water.

Claudia Peña Salinas, Itzkan, installation view, PROXYCO Gallery, October 2020 [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

JR: At PROXYCO what really struck me was the wall color and how that was as much a part of setting the scene as the sculptures themselves. I was wondering how much of this is planned ahead versus getting to the space, and seeing the sculptures in the gallery, and deciding then what the installation looks like.

CPS: I always think of the exhibition as an environment, so I will always make a model and play around with sculptures but also [with] the possibilities of painting walls. In the case of PROXYCO the space resembled to me almost a pyramid, because it’s one wide room and then it starts to become smaller. There’s three rooms, so I thought maybe if I paint them, then it starts to create this almost pyramid differentiation. And since I was working with the pyramid of Kukulkan and the site of Chichén Itzá, it was very appropriate. And also I found that there was access to a basement. So I thought, how great that I can then guide the viewer down to an underground space. There are some ideas, and then, when I see the space, the ideas start to grow from there.

Claudia Peña Salinas, Itza, 2020, brass, dyed thread and salt, 72 x 120.5 x 120.5 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

JR: Where did you first learn about legends and histories and myths around deities, and how do you continue to learn about them?

CPS: I spent some time in Mexico City, about 10 years ago, doing a SOMA summer residency. I was staying very close to the National Museum of Anthropology. In that museum there’s a library, so I was able to dig through some dissertations. Guidebooks that I buy on eBay are great—from the 60s and 70s—but they’re mostly for tourists, but they’re great because they’re very concise, and have great pictures. It can go from dissertations, very serious books, to, like, a pamphlet.

JR: I think your work also straddles the difference between a cultural anthropological lens, and this touristic view. I’m thinking specifically of the piece with the postcard from the PROXYCO show, and how these sites are changing in relationship to tourism.

CPS: Oh, Cenote II?

JR: Yeah.

CPS: I overbuy postcards. A lot of times, before I’ve been told what the space is, I will start thinking about the idea through postcards, for some reason. I’ll go and buy a bunch of [them]. Sometimes they don’t even make it into the exhibition. I don’t know if you see back there, but things on my wall right now are for another show I’m working on, and there are three postcards there. With Cenote II, that postcard [is] probably from the 60s. That postcard shows the Cenote—you have the tourist on one side, and then I wanted to have the other side be without figures, so in a way you’re looking at the Cenote, you become those figures that were in the postcard.

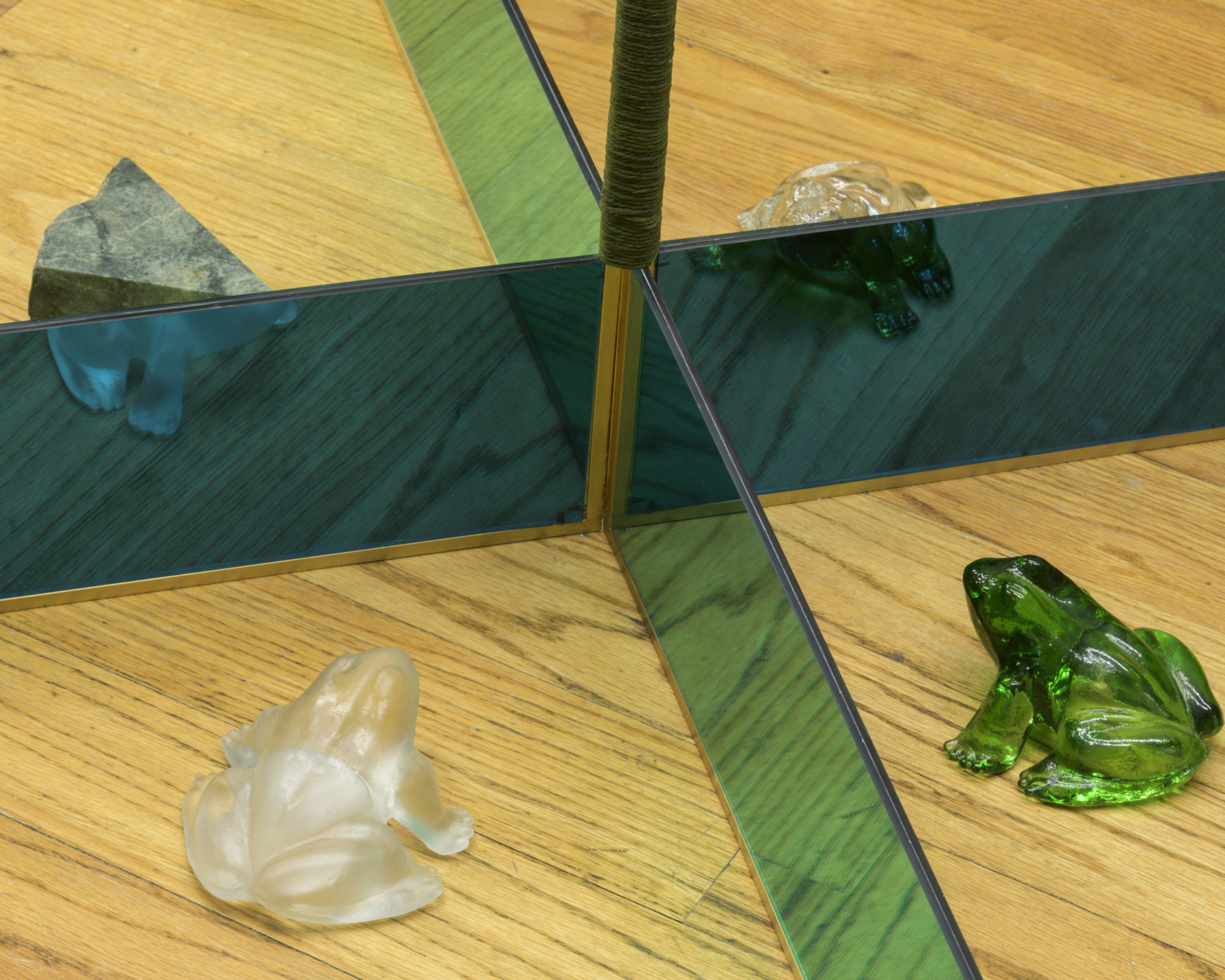

JR: Totally. In that piece, too, there are reflections that overlap and merge, and these glass frogs kind of eclipse each other—I thought that was brilliant. Could you talk more about those frogs and how transparency and reflection [function] in the work?

Claudia Peña Salinas, Cenote II (detail), 2020, brass, dyed thread, postcards, glass frogs, and jade, 39 x 48 x 48 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

CPS: There [are] three colored frogs, and then there’s a jade stone in there. It’s only by the viewer moving around—it’s a trick of the eye—[that] you’re able to see. There it is, there it disappears. That was an idea [about] how things are always in transformation. I always think of trickery, or mimicry; I want it to be kind of up front. Like you know you’re a participant, and you’re creating it. That’s why I’m interested in the materials remaining what they are. I’m not camouflaging something to be something else. You are an active participant.

JR: Yeah, it’s an honest mimicry. It’s not deceptive, and I think that totally makes you, as a viewer, wonder how you’re implicated in it and [become] more aware of your own actions in moving around, because [the experience is] not about something being done to you, it’s the way that you interact with these materials as they are.

CPS: And you can never comprehend the totality of the work. With each experience, there is always this shift of the materials, this transformation, as with stories and myths.

JR: You said that your work trails on minimalism. The grid [that] appears throughout your work, how do you deploy it with a sense of, or in spite of, modernist logic? Because I get a more spiritual [sense than I do a] rational sense from your work.

CPS: I think it’s [more of] a structure for narrative than for myth, for me. Like, here’s a container, and then I can add these things, so instead of making it a very austere, cold thing, it’s actually embedded with personal context. And I feel, like, people [such as] Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who I’ve always admired—he was employing this minimalist form but then adding all this cultural, personal stuff to it. There’s something I was reading [by] Rosalind Krauss. It’s an essay that she wrote, “Grids,” and she’s speaking of grid space—that within it the work can function as a fragment of a larger infinite, which is beyond the frame. That resonated, because when I’m pointing to these pre-Hispanic myths or stories, it’s really just fragments that I’m giving you, too, because that’s all we have. These stories were left to us, written at the time of colonialism, by Spaniards.

JR: I feel like your negative spaces really hold mass, and you carve entire cubes with just these light lines, and your sculptures often feel architectural to me. I wonder how you think of this negative space. Is it a residence for a spiritual figure, or is it a space to be inhabited, and what’s the viewer’s relationship to that?

CPS: It’s an interesting question, because I’ve often thought about that, too. These spaces do hold some kind of sacredness to them, but I couldn’t clearly say. One thing that I’m sure of is that they were thought of with the viewer in mind. It’s important to have them be these line drawings, not to have them be imposing. [They’re] very airy … yet they hold presence.

Claudia Peña Salinas, Chacmool II, 2020, photocopy and wax on wood panel, 20 x 16 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

Claudia Peña Salinas, Jaguar II, 2020, photocopy and wax on wood panel, 20 x 16 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

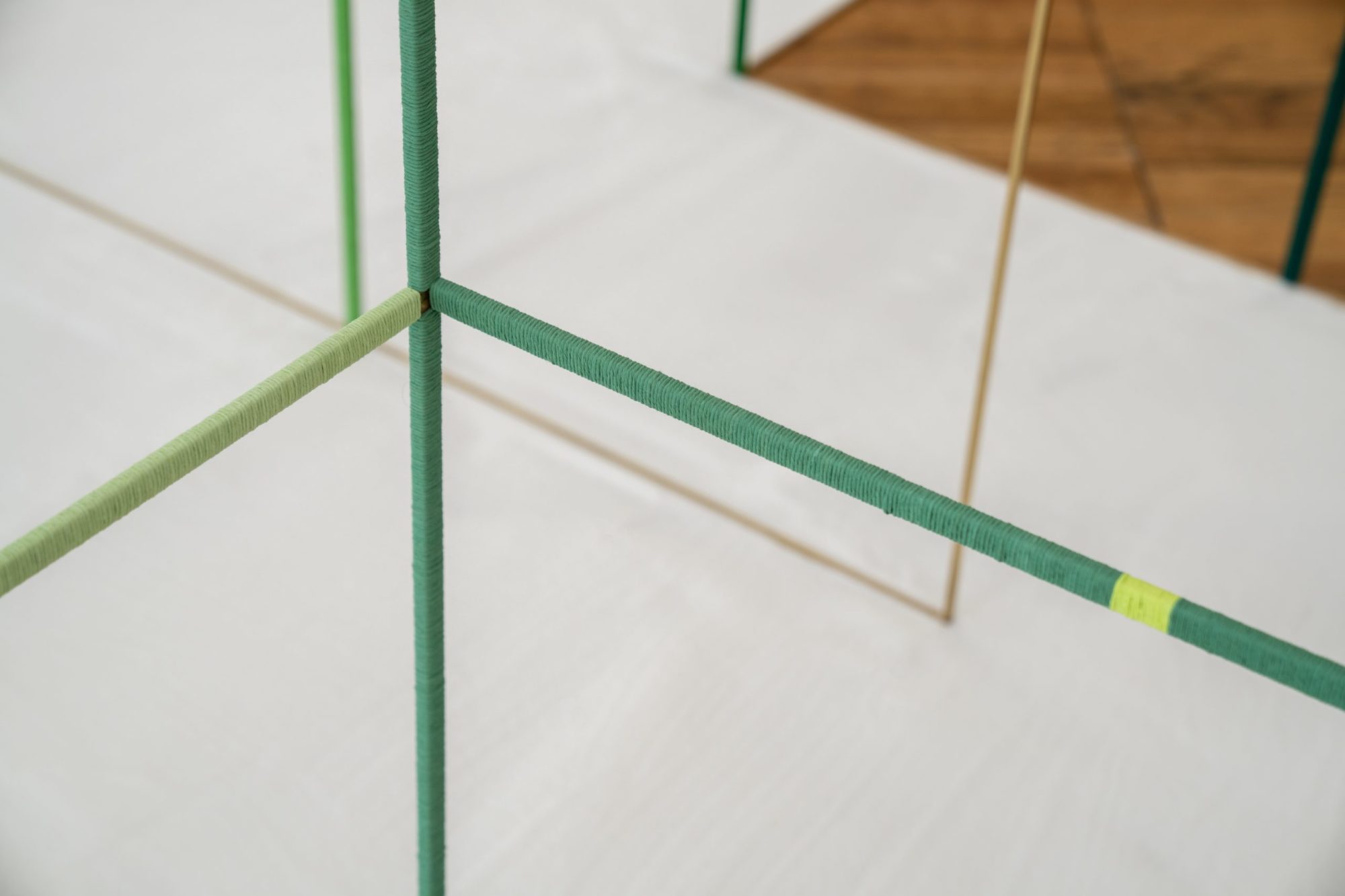

JR: I want to talk more about your use of thread, because these tiny threads have so much weight and mass to them in a way that I’ve never seen before.

CPS: There’s a whole process. My studio becomes a dye lab, and it’s a moment when I can also play with making a blue go from light to dark—very painterly moments that make sense because I was trained as a painter. Maybe you’re referring also to the hanging works. In those, when you look at them from the sides it appears as if all the threads are coming together—this kind of hovering of color happens—and you can see through it, but it’s also in a space, holding its own. Thinking of color, and color having some kind of emotion, I’ve always liked the work of Anne Truitt. I just saw a show at Matthew Marks Gallery, and now she’s making these squares—they were more like paintings. Thinking about Anne Truitt in relationship to my work makes sense sometimes.

JR: I want to talk more about language in your work. Could you talk about your approach to titling?

CPS: They come always from the combination of words that are from indigenous language. In the case of the show in PROXYCO here in New York, the name of the exhibition is Itzkan, and I was working with the Mayan language Itza. Itz means several things, but one is magic, and kan means serpent, so that’s one place where I have used both, combined these two words. But there were sculptures [that] were using just a word, like Ich, which means eye, or Tunich, which means stone. I think that titling these sculptures is giving them a name and giving them their own—I don’t want to say personality, but individuality. Then there are times when the words are combined to create another entity, like in the case of a sculpture that I had in the show in the Whitney, called Tlalicue. I combined the world tla from Tlaloc, and the world licue, from Chalchiuhtlicue, and it made sense because [of] the monolith that I was referring to. It’s always been kind of contested as to who this monolith really represents. Does it represent Chalchiuhtlicue? Does it represent Tlaloc? So I thought, here’s a third. It functions like that. Titling is a very hard thing. I feel like most artists, if you ask them, they’re like, ugh, titling. [laughs] I want [the titles] to mean something.

JR: I also think there’s a structural component to language, where there are these prefixes and suffixes. I can almost see a parallel to how you use color and motifs, where it’s like assembling these different parts that together take on a new meaning.

CPS: Yeah, almost like building blocks.

Claudia Peña Salinas, Itza (detail), 2020, brass, dyed thread and salt, 72 x 120.5 x 120.5 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

JR: Exactly.

CPS: That’s why the modularity of these brass squares works for me. These things can grow certain ways and expand certain ways. It’s more playful, too, to create your own, and it gives them their own individuality. I’m not calling it, like, “Green River. “[laughs]

JR: [laughs] Or “Untitled.”

CPS: I heard that Vivian Suter, the painter, all her paintings are untitled, which is a huge headache for the registrar, when they have to deal with 300 Untitleds. [laughs]

Claudia Peña Salinas, Ich, 2020, brass, dyed thread and river stones, 72.5 x 29.5 x 120 inches [photo: Javier Morales; courtesy of the artist and PROXYCO Gallery]

JR: One other piece I wanted to talk about was kan, [which was] in the basement, [which made me] think about natural light and windows, and how those affect the reading of your work. It was cool that you carved a whole new space in the gallery. I think that was the most Instagrammed work, with the neon.

CPS: [laughs] Yeah, people love it!

JR: Was that your first time working in neon, and have you approached working in neon before?

CPS: No, actually that neon tube, I can’t believe it still works. It’s from an exhibition that I did for an open studio when I was at Hunter College. It had been [around] the time that Obama had become president, so how many years is that?

JR: Like, 10 or 12.

CPS: What that neon does, and what I remember from having used it at Hunter, is that with the green you have the after-effects. Again it’s a perception thing that happens by being surrounded by this green, when you come out, there’s a little after-effect of seeing the normal light become pink. It’s a little visceral, in a way that now it’s kind of gone into you, the visual.

JR: Another thing I wanted to talk about was your exhibition with the High Line.

CPS: It’s a video exhibition that the curator Melanie Kress put together. A group exhibition called Memory Palace, about photography, and how moving images are used for storytelling and memory. The video that I will [show] is the same video that I had at the Whitney, called Tlachacan. It’s dealing with Tlaloc. I’m excited to see this video with all these other stories, and see how they connect, and for the public to see it again. The video narrates this searching for the monolith and all the copies that exist, and again, this kind of unclearness about if it’s Chalchiuhtlicue or if it’s Tlaloc. In March I’m going to go back to Mexico to continue [working] on a new video, and this one will deal more with Chalchiuhtlicue, and it will also have things from my trip last year to Japan. So that’s kind of like this Tlachacan video, [which involved more than] three or four years of going back to Mexico, and finding copies, and encountering more moments that make sense within a story line. It’s a very loose story line, and then it starts to kind of become something. I just kind of shoot, and it’s a travelogue kind of thing, so there’s lots of musings. There’s a great soundscore that I collaborated on with Pedro Martínez-Negrete, so there’s sounds that [were] made around the time of the 2017 solar eclipse. I don’t know music, but I know how to make sounds, and I created a big archive of all these different sounds that Pedro then arranged.

JR: That kind of echoes these structural components of language we were talking about, where you have prefixes or suffixes, like you have the instruments but you’re creating something new out of them.

CPS: Yeah, exactly, it’s the ingredients. I don’t cook much but I guess I am always cooking. [laughs]

***

This interview originally appeared in ART PAPERS Spring 2021 // Mimicry, Camouflage, Transformation.

Jack Radley is a Brooklyn-based writer and curator. His writing has been published in Artsy, Berlin Art Link, Boston Art Review, Cultured, Hyperallergic, Sixty Inches From Center, Temporary Art Review, and Whitehot Magazine, among other publications. He is a co-founder of New York-based global curatorial project ACOMPI.