Chrysanthi Koumianaki

Chrysanthi Koumianaki, Economy Is Wounded, 2013, digital print on paper, pencil on paper, collage [courtesy of the artist]

In 1946 Jorge Luis Borges commented on the individualism of the Argentine. He attributed this quality to the fact that the Argentine "does not identify with the State," because "the governments in [Argentina] tend to be awful, or an inconceivable abstraction." "One thing is certain," Borges continued: "the Argentine is an individual not a citizen." There couldn't be a better description of the Greek.

Share:

Of course, after more than six years of austerity, this condition has changed slightly. The financial crisis has brought forward questions of citizenship and the state, but also a much-needed self-critique. One reason for this self-reflection is the country’s renewed lack of faith in its own currency. In the first chapter of his book The Making of the Indebted Man Maurizio Lazzarato uses a phrase from a Greek union member responding to the proposed bailout: “This isn’t a rescue; it’s a sell-off.”1 And it’s the ideal slogan with which to enter the realm of currency failure, the mechanisms of debt, and the credit system.

Greece is the most recent and flamboyant mascot—or guinea pig—of indebted countries worldwide, dragged into a vacuum of perpetual owing. As Lazzarato argues, the capitalist drive to profit from crisis weakens the state itself, which is “a fundamental structure for political control and the formation of subjectivity.” The Greek state, however, is one that the Greeks themselves never quite believed in, and is thus a state not only in deep recession and on the constant verge of default, but also one in identity crisis. Writes Lazzarato: “The debt economy first reconfigures the sovereign power of the State by neutralizing and undermining one of its regal prerogatives, monetary sovereignty, that is the creation/destruction of money.”2 Not only is the economy of the country damaged, but the structure and fiber of its society, and its citizens’ faith in the future, is walking wounded.3

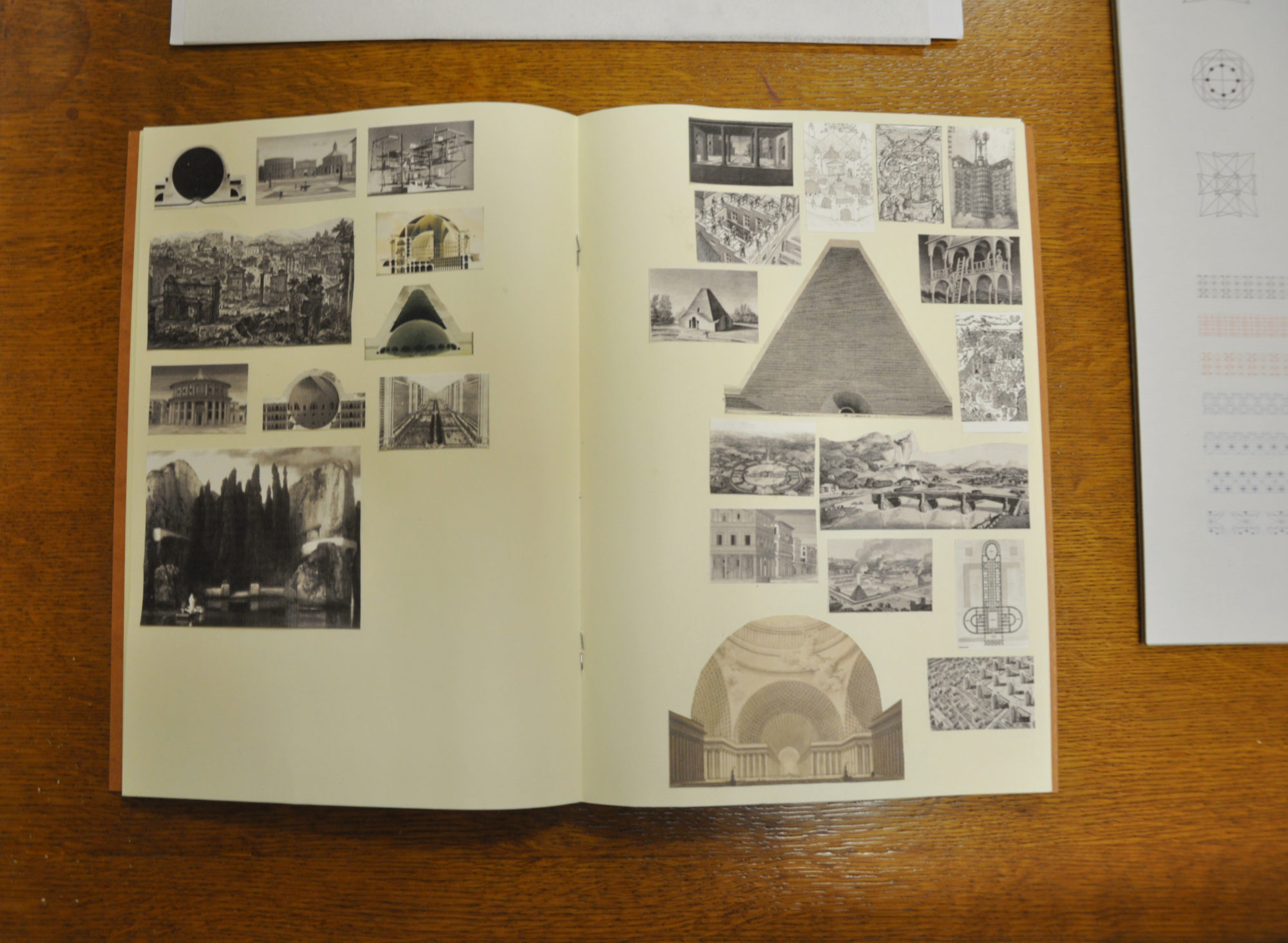

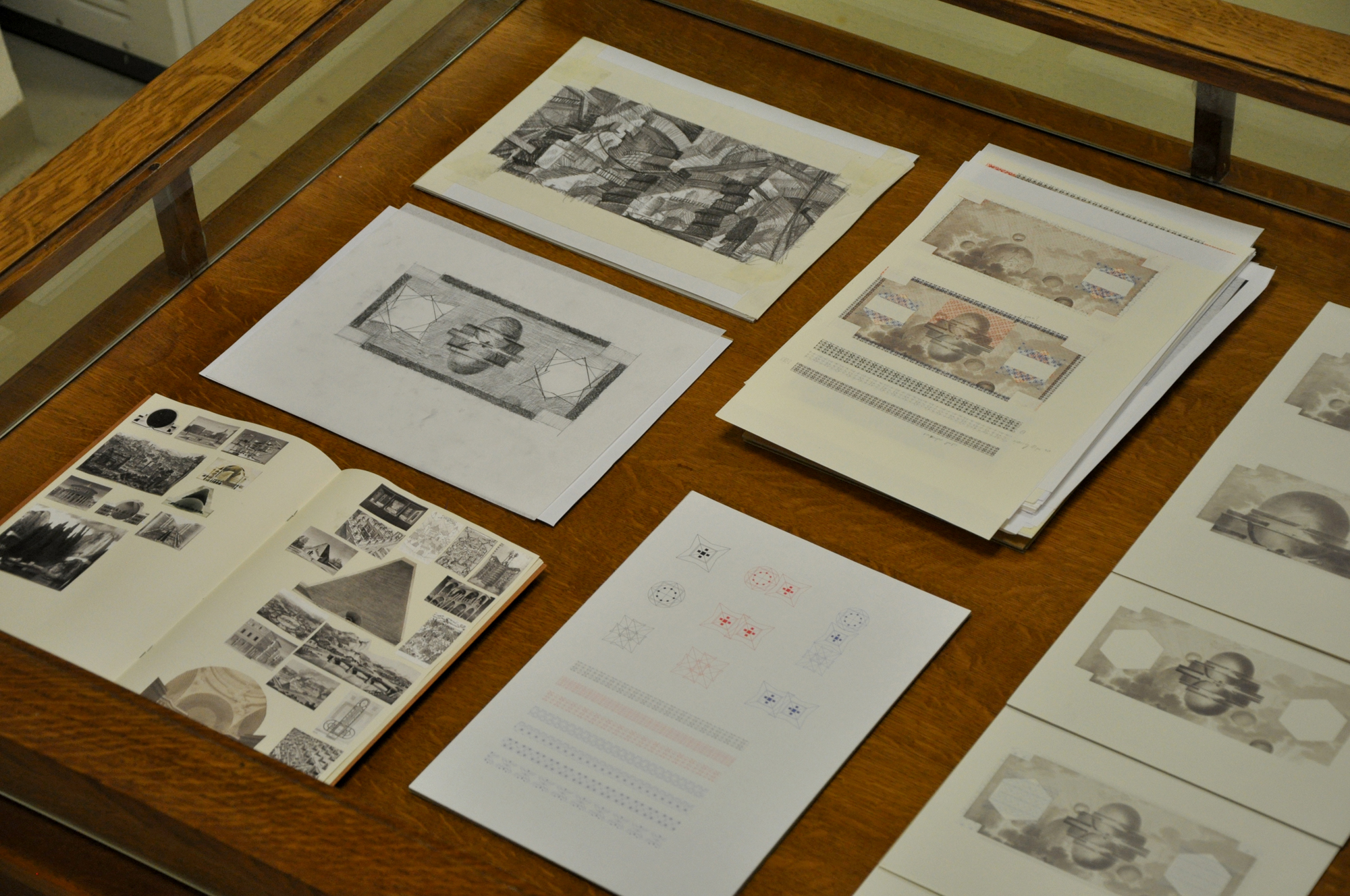

Greek artist Chrysanthi Koumianaki lives and works in Athens, where she has seen the financial crisis unfold slowly since 2008. Her work examines Greece’s present condition by exploring the value of currencies (hard, virtual, and symbolic) while revisiting the notion of utopia. These themes have resurfaced in her work of the last three years, which has also begun to take inspiration from political slogans used in demonstrations—whether from the streets of Paris in May 1968 or those of Athens in the 2010s. Making its debut in 2013, for example, was Koumianaki’s Economy Is Wounded, a mixed media installation in a vitrine that derives its title from a French 1960s slogan, “the economy is wounded, I hope it dies.”

Chrysanthi Koumianaki, Economy Is Wounded, 2013, digital print on paper, pencil on paper, collage [courtesy of the artist]

liana Fokianaki: You presented Economy is Wounded at the Historical Archive of the National Bank of Greece, then at the Fourth Athens Biennale, “AGORA,” in 2013. How did the work come about?

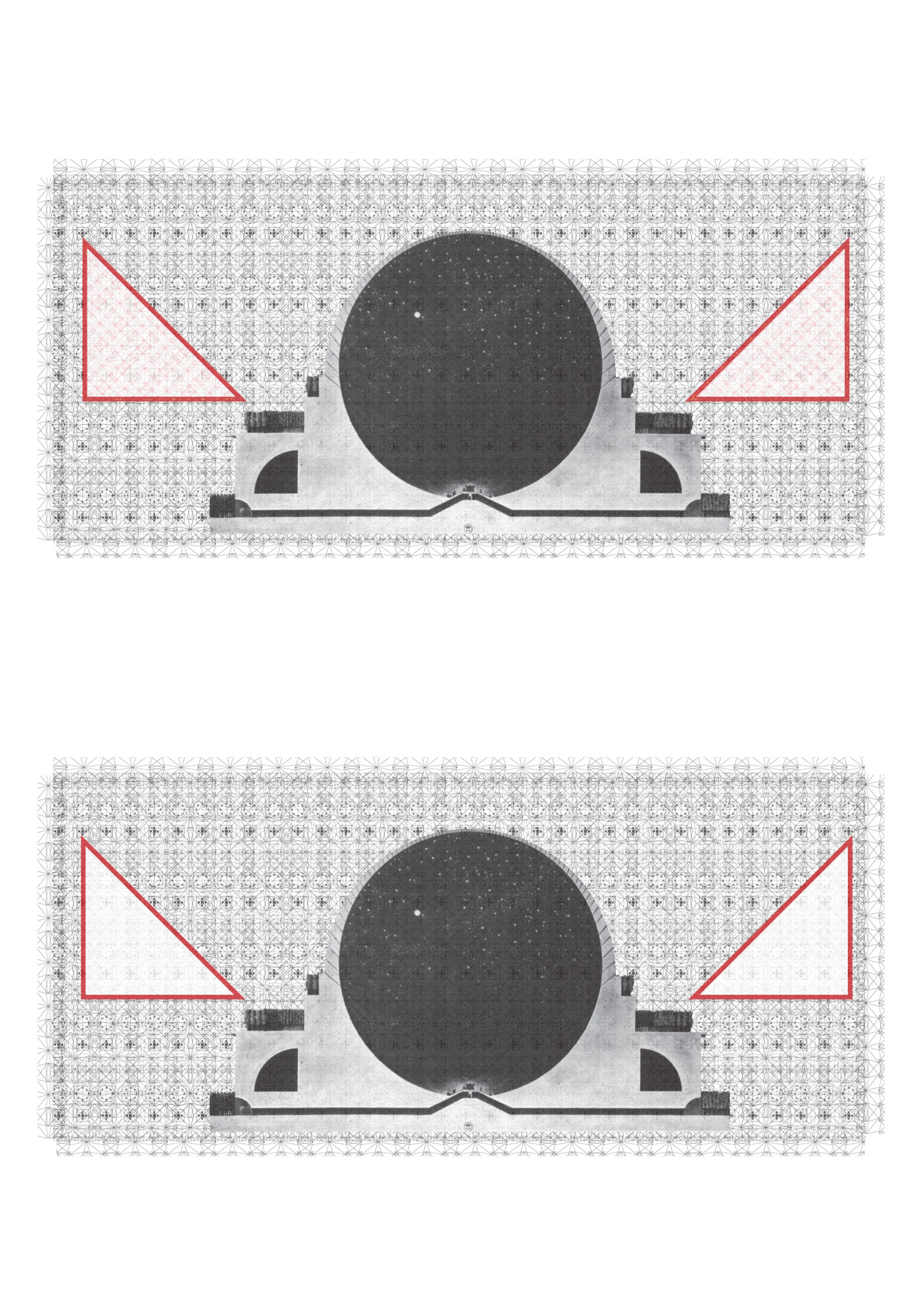

Chrysanthi Koumianaki: The starting point of the work was the archive of the National Bank. When I visited the archive, I was really taken [with] their collection of banknotes, and especially with the tests, proofs, and drawings of realized and unrealized banknotes. Because of my background in graphic design, I’ve always been interested in mass production, printing, and typography as recurring instant processes, and in this particular coding of the printed object, which is used to communicate an idea. From this viewpoint, I started looking at all the elements that combine to make a banknote. There’s always a number, a figure, a building, or a landmark, decorative motifs, and of course a unique watermark. These parts that transform this piece of paper into something that carries the meaning of value signify a system of relations. Now, when examining the process of production, one digs deeper. Looking at each element separately, without the final image of the product … well, that takes them instantly out of context. Studying the stages of printing a banknote at the archive, I came across a sampler of a company showing images that a client—in that case, a country!—could use on its banknote. So, I decided to assemble my piece according to the bank’s process, while thinking of pictures that could be put onto these new designs. I’m interested in putting together different types of images that create interactions when juxtaposed, so I try to propose a sum of images as an imaginary reality, if you will. As a main picture for the banknote, I used an image of [étienne-Louis] Boullée’s Cenotaph for [Sir Isaac] Newton—an unrealized design. The motifs on the background of the bill come from ideal city plans, most of them unrealized as well. The banknote here is also shown in its production stages, not as a final product—and therefore without an exchanging value. So, we have a series of unrealized realities, put together as possible realities or nonrealities.

IF: Why did you choose Boullée’s Cenotaph for Newton?

CK: Boullée’s Cenotaph for Newton is a characteristic example of an architecture that is unrealized, but at the same time quite recognizable. And I recognize a futuristic essence to it. This juxtaposition of the banknote being for everyone (or of ideal cities being for all) with the idea of an unrealized futuristic proposal that is at the same time a highly symbolic design on various levels … I thought that was interesting to put side by side: [juxtaposing] an “old” architecture that now seems obsolete, and unnecessary, with a futuristic aesthetic that has a view toward the future.

Chrysanthi Koumianaki, Economy Is Wounded, 2013, digital print on paper, pencil on paper, collage [courtesy of the artist]

The economy appears as a living organism, wounded, and finally possibly, but not certainly, dying.

-Chrysanthi Koumianaki

IF: Well, what was the future in 2013 is now the present. After three years, how has your relationship to the work changed, if at all? Do you see the work as having a different relationship to the changing context of contemporary Greece?

CK: The slogan that inspired the title of the piece is a statement that I find intriguing but also exciting. It is so direct because it is referring to the “economy” in a tangible and linear manner. It personifies it, despite all the complexity and the contradictions that arise within the comment. The economy appears as a living organism, wounded, and finally possibly, but not certainly, dying. The “hope” in the slogan, however, reveals an immaterial network of relationships that are incomprehensible, irrational, and in a way distant. Considering the economy as a fiction, I decided to work on this scenario of looking closely at a banknote, understanding … the material aspects of [the] economy. At present I understand that I won’t comprehend the economy fiction, no matter what its material aspect is. Banknotes and coins are materials; they are also symbols and instruments projecting something that is actually uncountable: a complex system of relationships. Would there be an alternative option if we destroyed those symbols? … In my everyday life, and after three years living in the current situation, I understand that I give them more and more value, which actually contradicts my initial idea.

IF: Is there a romanticism in the aesthetic language of Economy Is Wounded? You chose to [show] the work in a display cabinet in a museum; you gave it a historical aspect, like a relic that is remembered, perhaps adored.

CK: I chose to display them in a vitrine because at the archives of the bank the bank notes were actually displayed in the same manner. I thought it would be appropriate to follow this as part of the process, and to see how it would function outside of that particular institution to use an established aesthetic language. I did this in my new work, Down with the abstract. Long live the ephemeral! (2016), which I am currently showing in Athens in a group exhibition called Through the Fog: Descripting the Present, curated by Nick Aikens. Here, I am borrowing slogans that I find written on the walls in the streets of Athens, as well as borrowing the manière of that practice by using marker pens. I consider these slogans as backdrops of a universal situation, expressed in a local manner. The slogans on the wall exist and are not always deciphered, but when they are noticed, or voiced in demonstrations, they become more intelligent, I think.

Chrysanthi Koumianaki, Economy Is Wounded, 2013, digital print on paper, pencil on paper, collage [courtesy of the artist]

IF: Why is this intelligence appealing to you?

CK: [It comes back to] “economy is wounded, I hope it dies”—treating the notion of an “economy” like a human being makes it tangible, even schematically. And this has a force. To make the intangible tangible also carries a lot of optimism. When you can manipulate something, you can win it, you are its master. My work with slogans began with that piece in 2013, which for example referenced the decorative elements on the back of the banknote used as a proof of genuinity. It is the most difficult part to forge. And there lies the interesting thing for me: what a good forger does is to present something falsified as a reality, as a truth, and if you see what they managed to do in May 1968, even briefly, was in a way to counterfeit a reality. For a fragment in history during these months in 1968, a utopia became a reality.

IF: What about the Greek reality, the current slogans and what they propose? Can we ever consider it utopian, even for an instant?

CK: From 2008 until 2014 I kept going to demonstrations, though gradually I felt I was losing interest. I felt extremely disappointed: in Greece, we had an established situation already that just perpetuates. Demonstrations at times feel like just a way to let off some steam. But is there hope if optimism is gone?

IF: So, since we are referring to May 1968, if we are to take the existentialist approach, it seems that through your work, you propose an attempt at making the impossible possible—even if it is purely for philosophical purposes. So, in effect you are putting a failed solution in a display cabinet—a dead being, like the economy in the 1968 slogan, as if in a natural history museum, there to be admired, but with a distance appropriate to its extinction.

CK: Well, I guess that could be an accurate description. I would very much like for this force majeure of the citizens to create something, for it to become alive, but at the current moment it is impossible for me to think of it as a forthcoming reality.

IF: So, in effect you just admire the utopia?

CK: And also all those [who] are still writing slogans on walls!

Iliana Fokianaki is the founder of State of Concept non-profit gallery, art critic and curator based in Athens, Greece.