Cecilia Vicuña: About to Happen

Artist Cecilia Vicuña hosted a collective performance at the Henry Art Gallery on April 27, 2019 [photo: Chona Kasinger]

Share:

At the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, Cecilia Vicuña’s precarios dotted the walls, forming a constellation of repurposed materials. Plastic bits, shells, stones, thread, and debris intertwined in a fragile dance. These sculptures are delicate, rustic, like little dinghies or driftwood rafts. They hung in an unsure balance, responding to enduring fears around environmental and humanitarian crises. Vicuña, who began her practice as a teenager, has made precarios since the 1960s. In this retrospective, the works consider dematerialization as a consequence of climate change, and they prompt broader conversations on displacement.

Cecilia Vicuña: About to Happen is Vicuña’s first major solo show in the US, originally shown at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia and exhibited at institutions nationwide. The exhibition featured installations, poetry, video, artist’s books, and more than 100 precarios. The Chilean artist has pulled inspiration from political events for decades, crafting consistent opportunities for aesthetic disruption. In particular, Vicuña’s material recycling practice has served as a lifelong protest tool. While she was in exile during former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet’s rule, Vicuña’s precarios illustrated his treatment of people as disposable. The precarios now defy a willful ignorance toward climate change and immigration in the contemporary political sphere.

Cecilia Vicuña, precarios, 1966- ongoing, Found-object sculptures [photo: Mark Woods; courtesy of the artist and Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle]

Cecilia Vicuña: About to Happen, installation view, 2019 [photo: Mark Woods; courtesy of the artist and Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle]

Their political contexts aside, the sculptures also emit a hopeful energy. In one corner of the exhibition, a narrow alcove was adorned with precarios, swaying as they hung from the ceiling. One viewer at a time could step into the skylit space among the sculptures and bathe in piped-in audio of trickling water from Vicuña’s film Semiya (Seed Song) (2015). The effect was rain, sun, and summer emulated. It was a shivering experience that highlighted Vicuña’s omnipresent themes—balance, weight, origin, and nature.

Whereas Vicuña’s precarios are rooted in the earthly realm, her poetry is expansive, weaving together the celestial and the unknown. In “Illapantac” (1998), a poem rendered in vinyl wall text, Vicuña describes a “fertile rite” calling upon song and water to mediate a transformation. A “heavy portal” is smashed, and it’s “time to decant, to begin”—the poem conveys an ambiguous emergency aided by the mythical powers driving nature itself. In “El Quasar,” another vinyl text poem, Vicuña reflects on the almost, the not-yet, the about-to-happen. “Form was not born from an idea,” she writes. “It was an idea vanishing.” Vicuña seeks the form before the idea to locate its origin story. She references this concept with the poem’s title; a quasar is a massive source of celestial energy, but it is also known as a quasi-stellar object—it is almost.

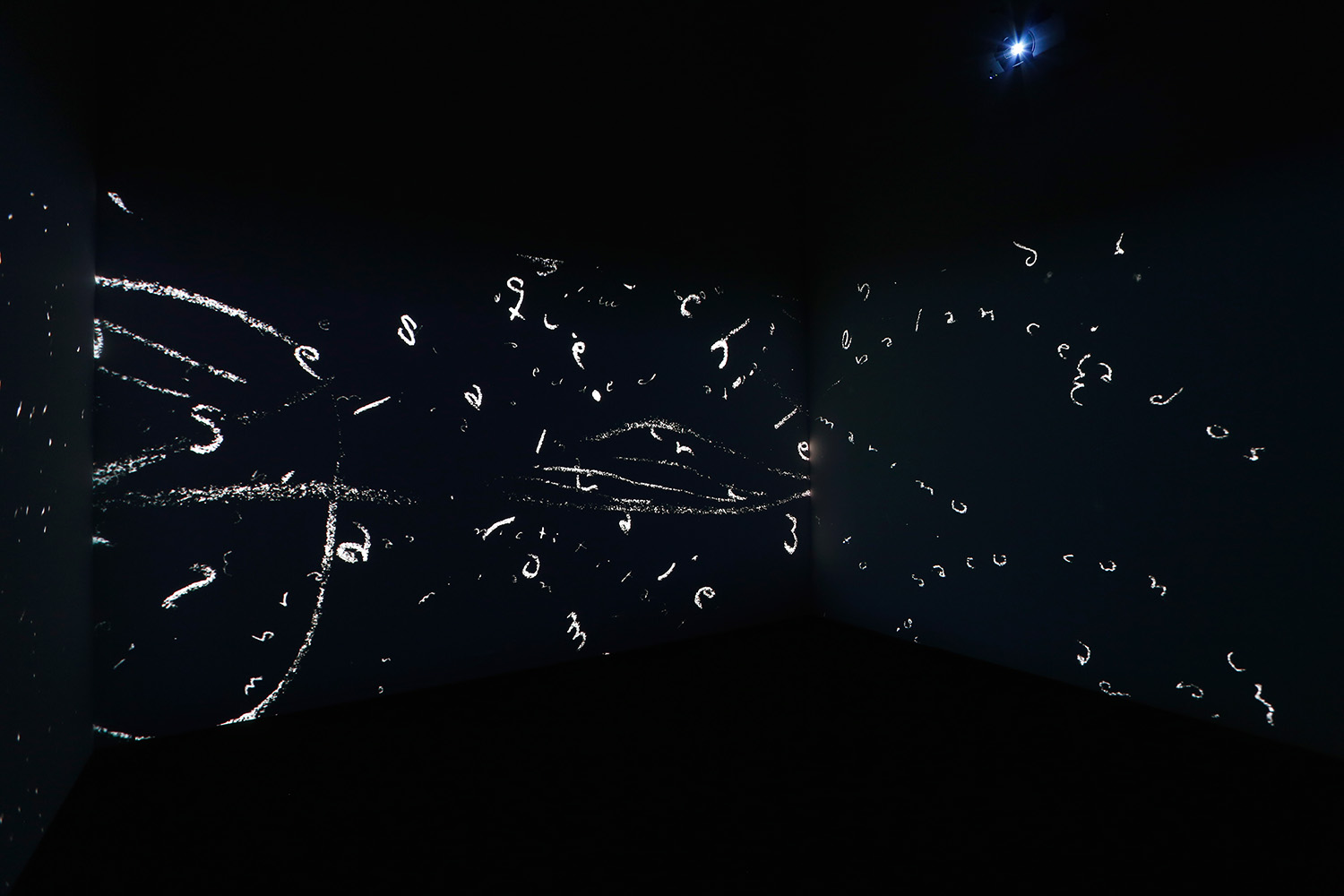

Cecilia Vicuña, La Noche de la Especies, 2009, Looping animation installation [photo: Mark Woods; courtesy of the artist and Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle]

Vicuña’s conceptual interest in origin and the almost is braided with her sociopolitical beliefs. In La Noche de las Especies (2009), an immersive three-channel video installation, Vicuña conjures a prehistoric ocean floor. The installation’s creation began with loose pencil drawings of oceanic bacteria, our planet’s first life forms, which were then digitally rendered by filmmaker Robert Kolodny and projected over three walls of a small room. Like the precarios alcove, Especies offers an intimate experience. The room is womb-like: warm, blue-black, and silent. In the animations, oceanic bacteria float, scatter, disappear and return, seeming both fragile and resilient. The installation’s title, which translates to The Night of the Species, brings to mind disappearing peoples and the near-extinction of oceanic life.

By honoring indigeneity and salvaging discarded materials, Vicuña’s work imagines a future strengthened by its past. Balsa Snake Raft to Escape the Flood (2017), a massive hanging raft sculpture, floats between ephemerality and necessity. Vicuña’s deft navigation of dualities shines here. The sculpture plays with suspension and weight, natural and industrial materials, land and sea, remembering and progressing. Nautical rope, fishing line, bamboo, plastic, feathers, and debris intertwine with new purpose. Vicuña scavenged these materials from the Louisiana coast, and they’re tethered to the memory of Hurricane Katrina. Perhaps this link explains why the sculpture hung from the ceiling: to honor the past, but also to rise beyond it.

Cecilia Vicuña: About to Happen, installation view, 2019 [photo: Mark Woods; courtesy of the artist and Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle]

Like Balsa Snake Raft, Burnt Quipu (2018) commemorates loss and embodies transcendence. In remembrance of recent California wildfires, Vicuña erected an installation of dyed wool that hung in knotted lengths, floor-to-vaulted-ceiling. The wool grazed the floor like giant tails, and from a distance, the installation looked like a dense wood of red, yellow, and black trees. Although loss is perceivable in the burnt blacks and browns, there was also a sense of unity and rebuilding. Quipus, or talking knots, were ancient recording devices used in pre-colonized Andean cultures. Cords were knotted in a complex system to contain readable information. Engaged with the parallels between text and textile, Vicuña has created quipus for decades, revitalizing the indigenous writing form to communicate abstracted information. Here, the quipu stored the collective memory of burned forests.

Vicuña uses fiber to create a connection or a disruption. Thread binds disparate refuse into new precario forms. Wool is used as a tactile expression of history. Vicuña’s artist books are often sewn together, embellished, or restricted with thread. In the text-based work Hilur (1997), she combines the Spanish word hilo (thread) with the English word lure, forming the neologistic title. Thread ties, anchors, and knots materials together. Quipu knots take notes and record memories. Vicuña uses this knowledge to create a language that can be touched.

Cecilia Vicuña: About to Happen was replete with moments of prayer for the displaced. Gliding seamlessly between mediums, Vicuña cultivates continued discourse around climate change and erasure by merging text and textile, migration and indigeneity, the mystic and the scientific. The resulting works are defiant, challenging, and embodied with an instinctive grace.

Lindsay Costello is a multimedia artist, poet, and arts writer in Portland, OR, with an academic background in textile research. Her critical writing can be found at Hyperallergic, Art Practical, Art Discourse, 60 Inch Center, this is tomorrow, and Textile: Cloth and Culture, among other places. She is the founder of soft surface, a digital poetry journal and residency, and the co-founder of Critical Viewing, a recurring web and risograph-printed publication aggregating contemporary art events in Portland. By day she works at the Portland Children’s Museum.