An Eye for An Eye — Bambitchell’s Bugs and Beasts Before the Law

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (screenshot), film and video installation, 33 minutes, 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD Video, 5.1 surround sound [courtesy of the artists]

Share:

“On the sixth day of June, at precisely one o’clock after midday in Erwin, I invite you to witness the most astonishing circus act for the fee of one single nickel,” the narrator of Bambitchell’s Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (2019) intones flatly, as cranes haul heavy material past the raw skeletons of high-rise buildings under construction. It’s the final chapter of the 30-minute essay film, within a section titled, in ornate lettering, “Book V – No. XXIV: Electrocuting the Elephant.” The narrator tells of Topsy, who is described as the prized elephant of a popular circus in Erwin, Tennessee, and who suffocated her trainer after he prodded her with a pitchfork. It was 1916, and—as Bambitchell’s narrator explains—the circus owner faced a conundrum: How to balance his liability for the incident against his audience’s desire for spectacle. Topsy was brought to the town square and hanged from a construction crane four feet above the ground until the machine collapsed under her weight. The crowd of curious onlookers included Thomas Edison—the story goes—who came forward and offered to electrocute Topsy using his newly developed direct current. In this moment, the film’s complex sound design suddenly jolts off course, replaced by a numbing, high-pitched ring. Then, silence. An orb of white smoke billows in the centre of the screen as cranes continue to move in the background—it’s the palpable feeling of aftermath, destruction, loss.

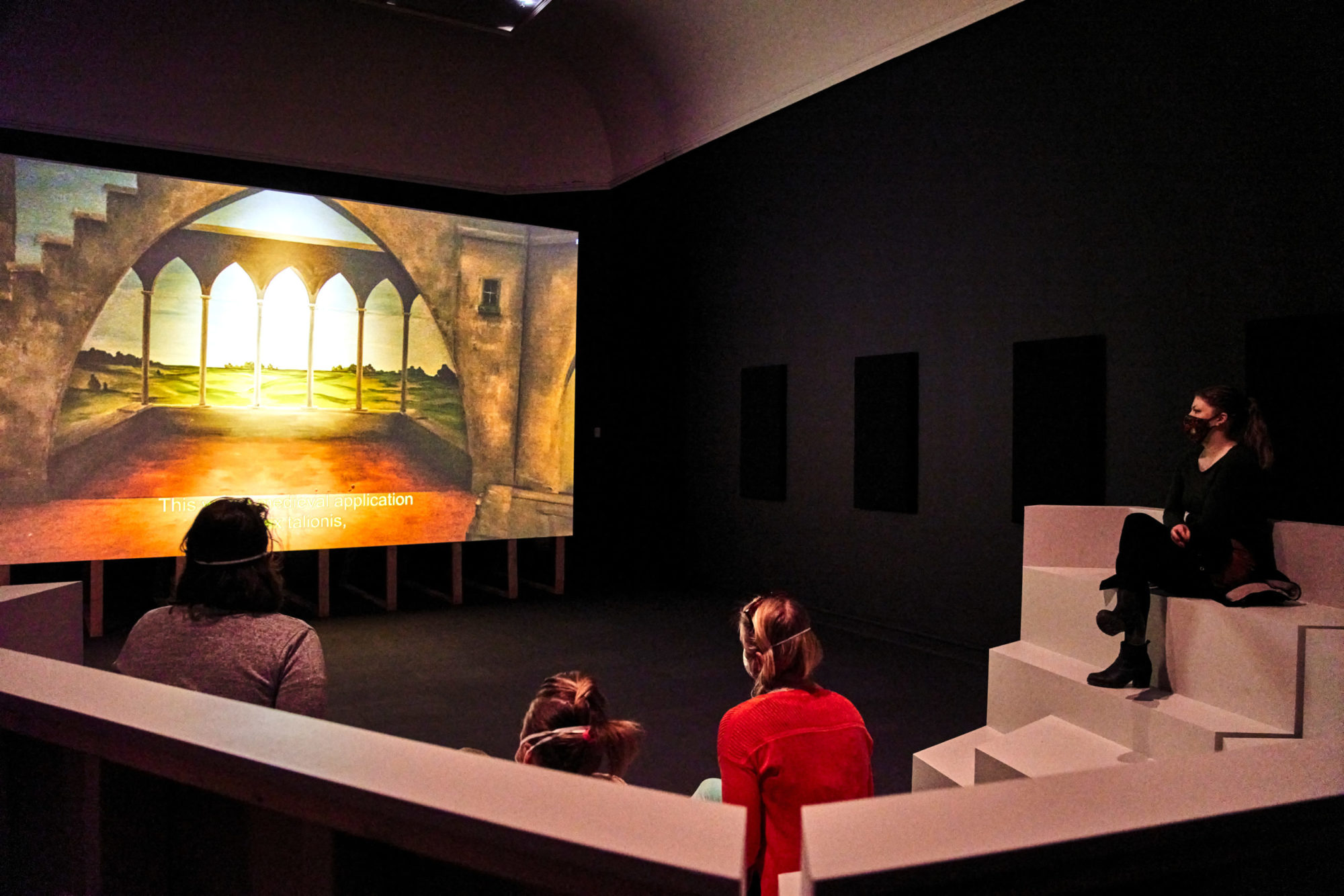

In describing Bugs and Beasts Before the Law, I feel compelled to begin here, at the film’s conclusion, in order to work backward through Bambitchell’s rollicking narrative. The work was recently on view at the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington in Seattle, and before that at Mercer Union in Toronto, Canada—where I was able to see it in person in 2019. Bugs and Beasts can be loosely summarized as a film about the practice of putting animals and inanimate objects on trial for so-called “crimes against humans,” common throughout the medieval and early modern eras. The film unfolds in five chapters, each focused on a different legal or ecclesiastical proceeding held in Europe or its colonial holdings. In the narrative shift from medieval settings, such as Falaise in 1386 and Basel in 1474, to Tennessee at the beginning of the 20th century, Bugs and Beasts works to remind viewers that such stories aren’t simply dusty curiosities from the footnotes of history books, but practices that fundamentally shaped how we came to understand the intersections between performance, punishment, and the social and legal limits of personhood.

Bambitchell: Bugs & Beasts Before the Law, installation view, 2021 [photo: Jonathan Vanderweit; courtesy of Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle]

As a film, Bugs and Beasts represents one iteration of an ongoing body of research into this particular slice of Western legal history. Bambitchell, a collaboration between Sharlene Bamboat and Alexis Mitchell, has produced multiple performances, print works, and a newly published artists’ book under the umbrella of the expanded project. The research began when Bamboat and Mitchell first came across a 1906 book by American linguist E. P. Evans titled The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, considered the foundational English record on the subject of animal trials. Evans’ research—its content and the physical book itself—manifests in various ways throughout the extended world of Bugs and Beasts, most notably through one of the tome’s many appendices: featuring a sprawling, chronological listing of “Excommunications and Prosecutions of Animals from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century.” Bambitchell reproduced this list in their artists’ book—recently published by the Henry Art Gallery—which acts as a speculative reconfiguration of the appendices to Evans’ text. Perusing his record is surreal and illuminating: The first listing dates from 824 CE, with the prosecution of moles in the Valley of Aosta (Northwest Italy); the last, the trial of a Swiss dog from 1906, the year of the book’s publication. The centuries between them reveal a veritable menagerie of pigs, sows, horses, rats, horseflies, mice, weevils, caterpillars, snails, beetles, turtle doves, worms, “she-asses,” and in one case, dolphins. Three of Bugs and Beasts’ five chapters are based on entries pulled from Evans’ appendix. When these cases are considered together, the broader political urgencies of Bambitchell’s work begin to emerge.

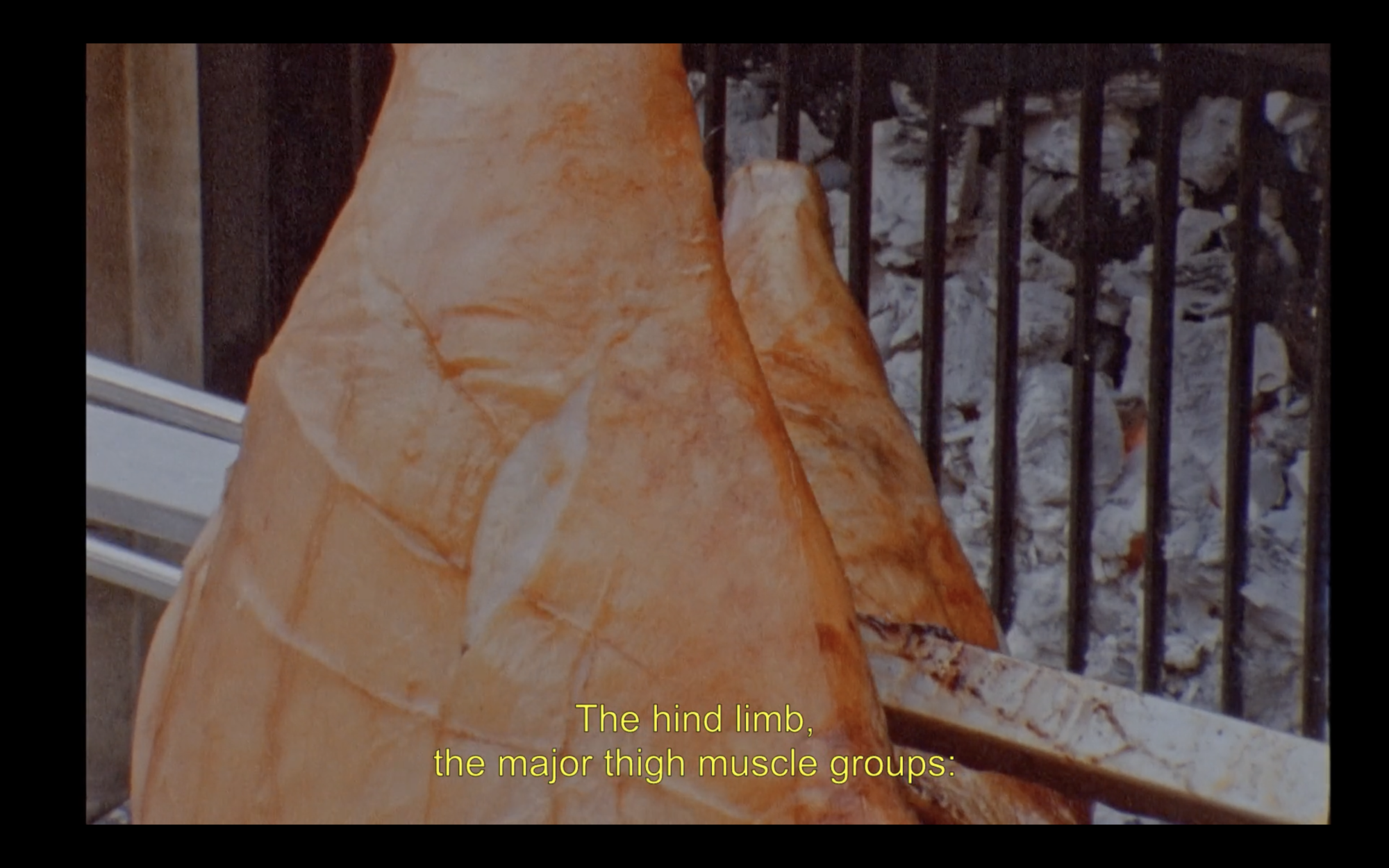

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (screenshot), film and video installation, 33 minutes, 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD Video, 5.1 surround sound [courtesy of the artists]

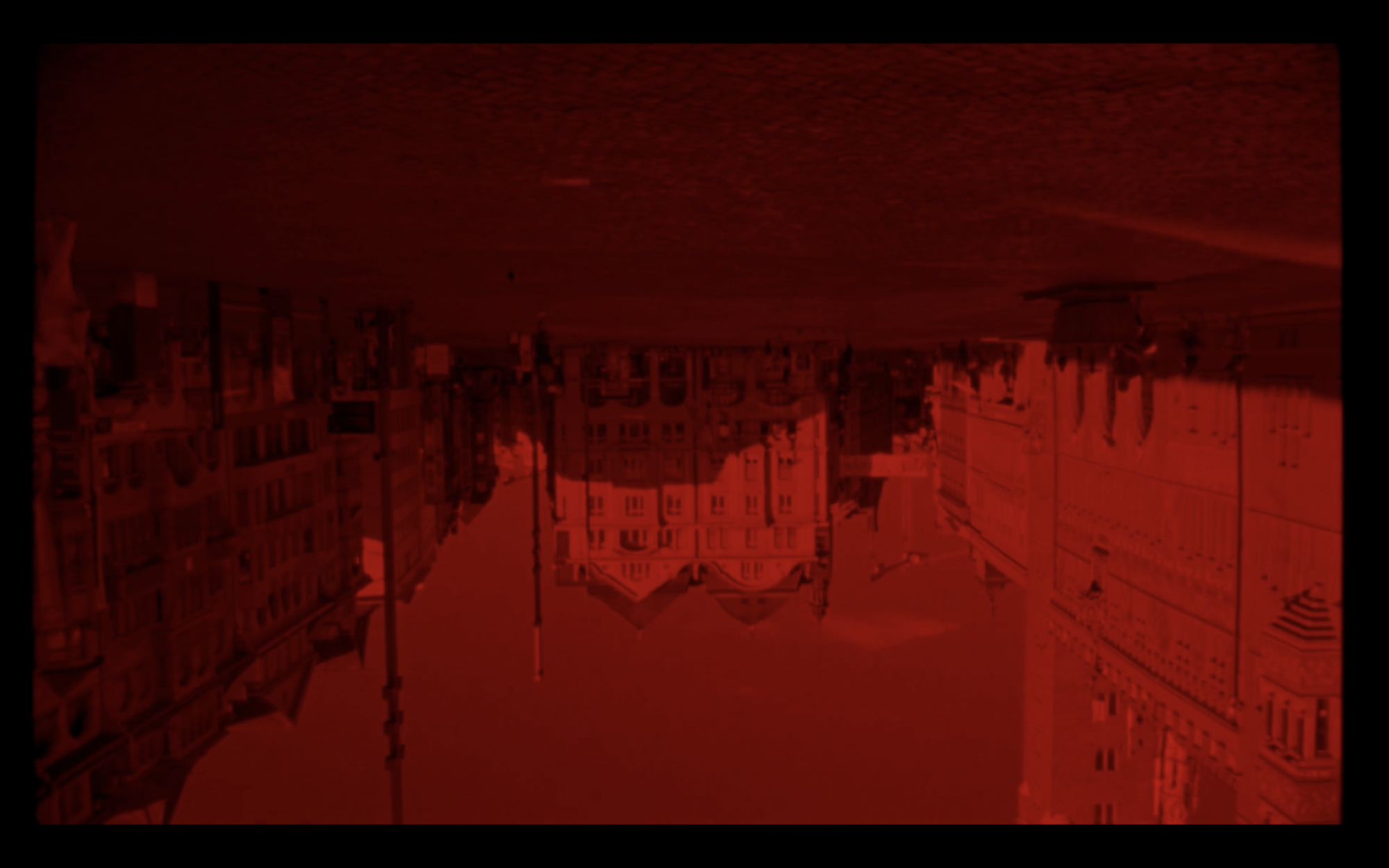

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (screenshot), film and video installation, 33 minutes, 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD Video, 5.1 surround sound [courtesy of the artists]

Set in Falaise (modern-day Northwest France) in 1386, “Book I – No. V: The Hour of the Pig” begins the film with the story of a sow, which was executed for killing a child. A pig is shown roasting on a spit—in close, almost excruciating detail—as Bambitchell’s narrator systematically reminds the audience of significant biological similarities between pigs and humans. The narrator also cites Evans’ text, describing how, during the height of the European witch trials, pigs were frequently prosecuted because they were believed to be easily corruptible by devils and demons. In juxtaposing these details, Bambitchell’s narrator begins to gesture toward a simmering social anxiety about the all-too-porous boundaries between human and otherwise, between our “enlightened” systems and our so-called baser natures.

“We, in detestation and horror of the said crime, and to the end that an example may be made, and justice maintained, have said, judged, sentenced, pronounced, and appointed that the said porker, now detained as a prisoner and confined in the said abbey, shall be by the master of high works hanged and strangled on a gibbet of wood nearest to the gallows of the high place of execution.”

While performing this proclamation, the narrator’s voice is fractured, expands upon itself, and erupts into a visceral mass of noise.

The film’s second chapter reports a radically different result for its defendants. In 1713, a cluster of termites was brought to an ecclesiastical tribunal for eating away at the wooden structure of a Franciscan monastery in Piedad do-Maranhão, Brazil. The lawyer appointed to defend the termites argued that they were simply acting upon their God-given need for sustenance, and considering that they had inhabited the region long before the friars, they were entitled to remain on their land. The judge ruled in the termites’ favour, demanding that they cohabitate peacefully with the friars in the abbey.

Set documentation of Bugs and Beasts Before the Law, 2019 [photo: Florian Clewe; courtesy of the artists]

As I write this, we’re on the eve of the Canadian national holiday, in the midst of a long-overdue reckoning with this country’s violent settler-colonial legacies—its historic and ongoing systemic harm against Indigenous peoples—particularly in regard to the genocidal impact of the residential school system. Although Bugs and Beasts remains tightly focused on its source material, its implications expand beyond this frame to obliquely engage with other difficult pasts and presents. The film’s narrator recites the Catholic Church’s declaration of a termite’s right to its own territory—the creature’s social and legal precedence over a colonizing power, having been there first—and the statement feels utterly laughable today; horrifically so. Not all human persons have been offered the same autonomy under European colonialism—or even the designation of “personhood” itself.

Bambitchell’s work truly shines here, in Bamboat and Mitchell’s capacity to present their research in ways that playfully negotiate the absurdities found within systems of power, while keeping a careful eye on the broader social and political implications of the stories they tell. Bugs and Beasts ranges tonally from flatly informative, to solemnly reverent, to the sweetness of nursery rhymes, building toward an ecstatic, almost evangelical crescendo; thanks in no small part to artist Richy Carey’s truly expansive sound design and the particular affect of Sukaina Kubba’s measured narration. Amid this wholly enjoyable rhythm, the film’s relationship to its own narrative authority remains complicated, perhaps even ambivalent.

This conflicted dynamic is felt most palpably in the musical interlude that punctuates Bugs and Beasts’ third chapter. The camera follows a meandering path through a wooded area while a disembodied chorus sings frenetically about the English legal designation of deodand: inanimate objects that were charged and banished for enacting harm against humans. An operatic voice declares, “Such a weapon must be banished from the village lest it taint / its inhabitants with its magical and malicious influence!” A harsh red circle is shown travelling across the forest as the song continues, like a symbol hunting for its chosen subject, ready to deem someone—something—as outcast, heretic, pariah. The music is infectious. I recall involuntarily tapping my toes along with its rhythm while watching Bugs and Beasts for the first time, and it remained stuck in my head for weeks as I’ve worked on this text. It is clear that Bamboat and Mitchell are well aware of the highly seductive nature of their film’s language; its power to galvanize, to produce an impression of unwavering truth from speculation and fiction. The chorus reaches its feverish peak, referencing some now-familiar characters and naming a few new ones as well:

The sword, the boat, the cart, the wheel, the iron, the statue, the shaft, the pig, the goat, the termite, the weevil, the ant, the spider, the rooster, the elephant! The witch! The saracen! The sodomite!

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (screenshot), film and video installation, 33 minutes, 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD Video, 5.1 surround sound [courtesy of the artists]

The witch, the saracen, and the sodomite. Up to this point, humans have been curiously missing from Bugs and Beasts, though not entirely absent. Bambitchell does little to hide the contemporary details of the settings, shot in various locations across Europe and North America. Cars drive past restored medieval buildings, far-off figures wander in and out of shops across the cobblestones of an old town square. Yet humans are rarely made central in the film itself: instead, their stories appear obliquely, allowing the emphasis to rest with the film’s nonhuman characters, and the all-too-human anxieties that circulate around their perceived subjectivity. This subjective decentering reminds viewers that the designations of human and nonhuman have long been kept malleable, able to shift in order to suit those in power.

“Book IV. – No. XIX: The People v. the Cock of Basel” tells of a rooster tried in 1474 for the act of laying an egg. The creature was assumed to have copulated with the devil—enacting an obscene, unnatural form of reproduction from which the cursed egg was produced. As Bambitchell’s story continues, the prosecution calls upon the criminal precedent of Johannes Alardus, who was convicted of sodomy and witchcraft for having “kept a Jewess in his house and [having] several children by her.” Although we cannot know the exact circumstances between Alardus and this unnamed woman, the implications are clear: Given her racialized status, their relationship was deemed as unnatural as a rooster copulating with the devil, and therefore labelled with the slippery, but highly punitive, social and legal category of sodomy.

As Silvia Federici argues in Caliban and the Witch (1998), the late medieval witch trials in Europe represented not a spontaneous “craze” or mob mentality, but a concerted, systemic effort to destroy the social, reproductive, and sexual autonomy of women in the early days of European colonialism and capitalist expansion. Federici maintains that the witch trials were

an attack on women’s resistance to the spread of capitalist relations and the power that women had gained by virtue of their sexuality, their control over reproduction, and their ability to heal. 1

Yet as Greta LaFleur argues in an excerpt of her book, The Natural History of Sexuality in Early America (2018), reproduced in Bambitchell’s publication, late medieval sodomy narratives were as much about Christian Europeans’ need to sublimate racial anxieties as policing nonreproductive sexual behaviour. In an analysis of medieval European captivity narratives—highly racist and Islamophobic stories wherein Christians are captured by Muslim “barbarians” from the Barbary coast of northern Africa—LaFleur points out that sodomy figures prominently as a tool of torture:

Sodomy, as these texts reveal, was understood not only as a problem of polity, discipline, social order, inclination, or innate depravity, but also as a particularly racialized behavior.” 2

And to recall the feverish peak of Bambitchell’s operatic interlude, the saracen—a medieval term used, primarily by Christian Europeans, as a shorthand for Arab Muslims and Turkish people—was named alongside the witch and the sodomite as prime threats to White, European, Christian, capitalist social order.

It is interesting that this unnamed Jewish woman appears, albeit indirectly, in Bambitchell’s narrative, invoked through a legal precedent to condemn another, she remains enmeshed within the dense language of performative legalese that would have been enacted in these trials. Watching Bugs and Beasts, I find myself returning again and again to the question of language. The spoken narration of Bugs and Beasts expands and contracts with such fluidity that the film’s language becomes powerfully embodied in its own right, despite the lack of corporeal representation on screen. The verbal prosecution of a pig is made jagged, massive, and wholly impenetrable through both vocabulary and accompanying sound design: “[W]e […] have said, judged, sentenced, pronounced, and appointed that the said porker, now detained as a prisoner and confined in the said abbey….” A deceptively sweet, simple nursery rhyme about the banishment of mice from a field of wheat (“Sortez, sortez d’ici, mulots! Ou je vais vous bruler les crocs!”3) demonstrates the malleability of language, its propensity for manipulation by those who enact power in a variety of ways—directly authoritative or subtly insidious. To carry this point home, Bamboat and Mitchell produced a series of photocopy transfer prints to accompany the installation at the Henry Art Gallery, each featuring found engravings alongside fragments of text (cited from medieval sources as well as Evans’ book). These prints are dense, collaged arrangements wherein language and notation become ornate, almost armor-like, wavering between legibility and opacity.

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (screenshot), film and video installation, 33 minutes, 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD Video, 5.1 surround sound [courtesy of the artists]

This brings us back to the story of Topsy the elephant, which is also introduced by Bambitchell’s narrator with a particular linguistic flair: “I invite you to witness the most astonishing circus act for the fee of one single nickel.” It only takes a quick Google search to realize that the narrative described in Bugs and Beasts is the amalgamation of two relatively contemporaneous events, as if the brutal killing of one elephant for profit and entertainment wasn’t enough. Topsy was electrocuted on Coney Island in 1903. Mary the elephant was hanged from a construction crane in Tennessee in 1916. Topsy’s death was filmed by Edison’s movie company—Edison himself is not believed to have been present4—and circulated widely as Electrocuting an Elephant, 74 seconds in length and possibly the first filmed death of an animal.

I do not mean to discredit Bambitchell’s narration, but only to suggest that this conflation of stories represents a strategic use of language in the work. In side-stepping the narrator’s presumed responsibility to strict veracity, the video produces a form of storytelling that subtly critiques the very authority it constitutes. In Caliban and the Witch, Federici writes that during the European witch hunts,

the word “gossip,” which in the Middle Ages had meant “friend,” changed its meaning, acquiring a derogatory connotation, a further sign of the degree to which the power of women and communal ties were undermined.5

Artist and writer Hannah Black elaborates beautifully on this claim:

Like a hero who is at home in the worlds of both the living and the dead, the gossip crosses back and forth between home and world, between the secret interior and the public exterior, carrying items to trade: shared knowledge, a shoulder to cry on, insight, fun.6

To view Bambitchell’s narrator—and by extension, Bamboat and Mitchell themselves—through the lens of gossip helps to situate them alongside the flows of history that Bugs and Beasts describes. Crossing between worlds, as Black writes, the gossip is not beholden to strictly delineated boundaries between fact and fiction; but, as we have seen, neither were the social and legal authorities of early modern Europe. (Nor are their present-day successors, I would argue.) In repeating the language of these systems of power, Bambitchell works to expose their absurd logics—can you believe he said that—and in connecting the stories of Topsy and Mary, the way a gossip might conflate two true stories that share a likeness, they remind us that these cruelties are systemic; the power to determine personhood and the authority to punish difference are two sides of the same coin. “All beasts and birds as well as creeping things were devils in disguise,” the narrator whispers. If gossip prompts us to look at power differently, it can ask us to forge new allegiances as well. Situated among my fellow creatures—large and small, human and otherwise—I lean in and listen for more.

Daniella Sanader is a writer and reader based in Toronto.

References

| ↑1 | Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2004), 170. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Greta LaFleur, “The Complexion of Sodomy,” in Bugs and Beasts Before the Law: Appendix A-L, (Seattle: Henry Art Gallery), 19. |

| ↑3 | Translated as: “Get out, get out of here, mice! Or I will burn your fangs!” |

| ↑4 | Additionally, counter to the video’s narration, Edison would not have been advocating for the use of his own direct current in an electrocution, but rather his competitor’s alternating current, as a demonstration of its danger. |

| ↑5 | Federici, 186. |

| ↑6 | Hannah Black, “Witch-hunt: gossip has always been a secret language of friendship and resistance between women,” TANK Magazine, Spring 2017, online. |