Carolyn Lazard: Living Here and Together

Carolyn Lazard, CRIP TIME, HD Video, 10 mins, 2018 [courtesy of the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York]

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A hand extends over seven pillbox compartments on an embroidered tablecloth. The image is taken from an overhead position with the hand partially obstructing the view of the differently colored compartments. The fingernails are painted gold. The compartments are yellow, blue, pink, green, and white. They are filled with differently colored pills too. There is a patch of bright sunlight on the tablecloth and there are a few pill bottles visible along the edge of the frame.

Share:

For artist and writer Carolyn Lazard, physicality, phenomena, and the very act of being are sites for exploration. In their 2019 text “The World Is Unknown,” they describe the body as an “undifferentiated mass of tissue and memory … an unknown place worth approaching with an openness and willingness to let it reveal itself to me.” Informed by their chronic illness, Lazard’s practice is one that is radical in its care and conception of the body: its healing, its trauma, and its possibility outside of our society’s strict conceptions of wellness and productivity. The artist, whose works were featured in the 2019 Whitney Biennial and exhibitions at ICA Philadelphia, the Walker Art Center, and the New Museum, uses moving image, installation, and writing to offer new ways of conceiving health and physicality—ones free from capitalist and other frameworks that understand the body and health only in binary terms. In videos such as 2018’s CRIP TIME—a mediation on the task of organizing weekly medications and pills—time, labor, and our perception of these two forces are Lazard’s mediums. The artist’s singular, unwavering focus on the act of medicating is a way of slowing and altering time. As in projects such as In Sickness and Study (2015–present), they create a space in which the often unacknowledged work of disability is given autonomy and priority. Over the course of the summer, I corresponded with Lazard about their art practice, the limitations of institutional critique, and the transformative beauty of disability justice frameworks.

Madeleine Seidel: I want to begin with talking about your 2018 video CRIP TIME, in which we see the preparation of pills for the week, with the bottles piling up around the corner of the frame and the sunlight slowly shifting in a way that signals the passing of time. There are really two sides to this video: the labor of illness and the ritual element of it. Do you find comfort in rituals like this, or is calling it a “ritual” a way of sanitizing the often-unrecognized work that goes along with being ill or disabled?

Carolyn Lazard: Filling pillboxes is more of a task than a ritual for me. But any task can become a ritual with a certain degree of attention. As a task, it certainly crosses the threshold between working and living. It points to all the uncompensated labor necessary to reproduce oneself day after day. While many disabled people are excluded from participating in the economy as laborers, most of us work really hard to stay alive under global racial capitalism.

Carolyn Lazard, CRIP TIME, HD Video, 10 mins, 2018 [courtesy of the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York]

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A set of hands sort seven pillbox compartments on an embroidered tablecloth. The image is taken from an overhead position with the hand partially obstructing the view of the differently colored compartments. The compartments are yellow, blue, pink, green, and white. They are filled with differently colored pills too. There is a patch of bright sunlight on the tablecloth and there are a few pill bottles barely visible along the edge of the frame. Deep red pills are held in the palm of one hand.

Carolyn Lazard, CRIP TIME, HD Video, 10 mins, 2018 [courtesy of the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York]

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A set of hands sort seven pillbox compartments on an embroidered tablecloth. The image is taken from an overhead position with the hands partially obstructing the view of the differently colored compartments. The compartments are yellow, blue, pink, green, and white. They are filled with differently colored pills too. There is a patch of bright sunlight on the tablecloth and there are a few pill bottles barely visible along the edge of the frame. Bright orange pills are held in the palm of one hand.

MS: CRIP TIME and your other works, such as Support System (for Park, Tina, and Bob)(2016), deal with time in alternative ways by relying on everyday markers of passing time—flowers, pills, sunlight. Did your filmmaking and performing practice inform the manner in which you approach time, or were you drawn to these mediums [while already] wanting to approach this topic?

CL: It’s challenging for me to compartmentalize my work into its medium-specific formal qualities and its areas of study. They feel really irreducibly entangled. I make videos and performances, and because of that I have an intimate relationship to time, duration, and repetition. I would say that time—rather than, say, film or video—is the primary material of the moving image. The moving image has an ideological attachment to narrative. Its linearity can feel violent when one moves through the world with a body or a desire that contradicts normative ideas of progress or forward motion. In my work, I explore Black, queer, and crip temporal frameworks in which time is recursive. It stutters and stops, slows down, and speeds up. The mundane experiences of the everyday can feel like a space of reprieve from the compulsive indoctrination of the master clock. My bodymind just can’t keep up, and my practice is an attempt to think and feel through the radical possibilities of incapacity.

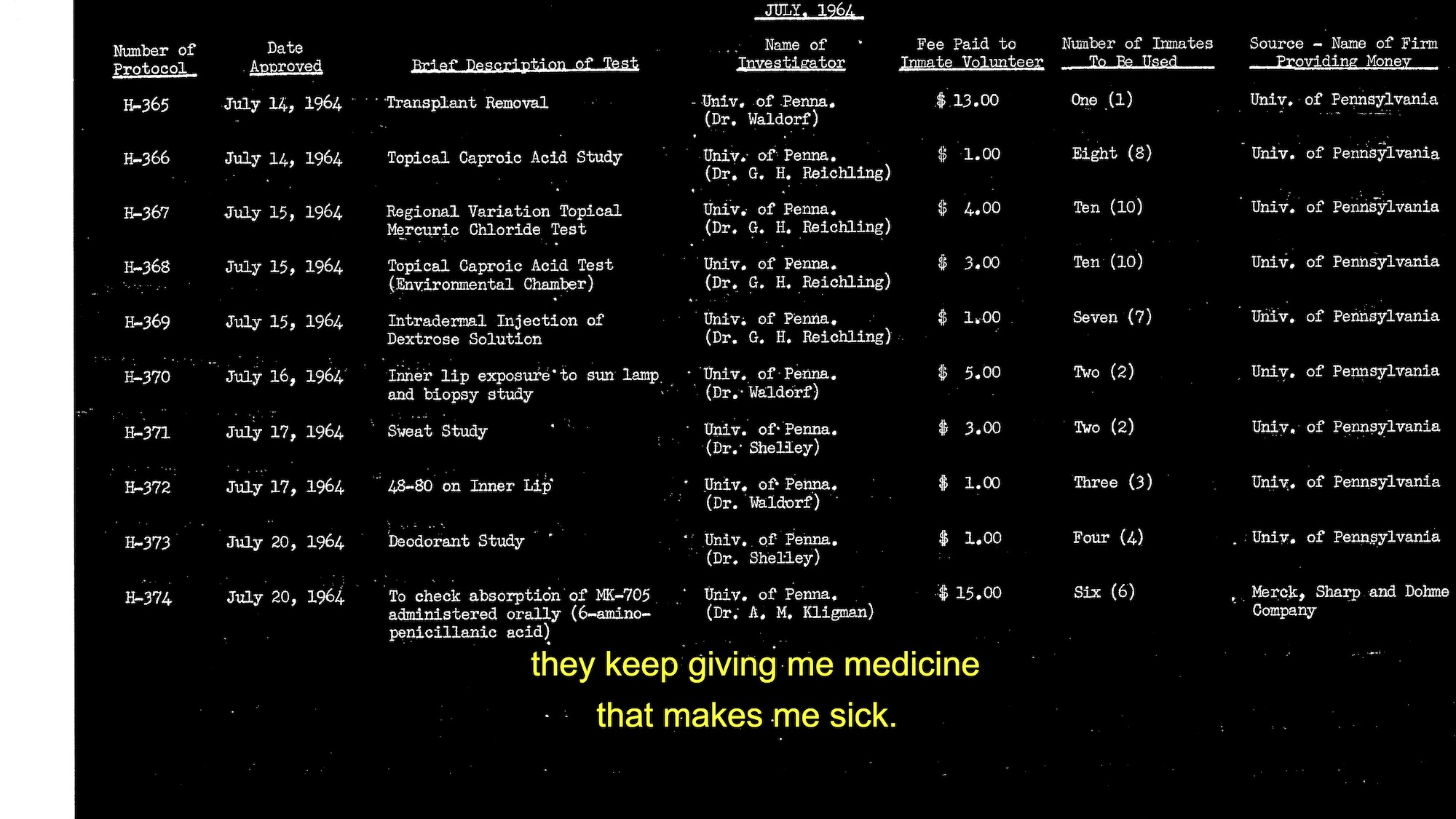

MS: One of your more recent installations, Pre-Existing Condition (2019), was included in last year’s Colored People Time: Banal Presents at ICA Philadelphia. In any other institution, Pre-Existing Condition would be a powerful work about the abuse of incarcerated people in America, through the archival records of University of Pennsylvania professor Albert M. Kligman on inmates at Holmesburg Prison. Yet, because this work was installed at ICA Philadelphia (which is located on the campus of and is otherwise associated with the University of Pennsylvania), it becomes a searing critique of the alliances that arts institutions make with larger entities. As an artist [who] exhibits at arts institutions across the country, do you see institutional critiques in exhibited art as a critical practice as museums rebuild post-pandemic?

Carolyn Lazard, Pre-Existing Condition, HD Video, 6 mins, 2019 [courtesy of the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York]

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A scanned document of a table of information pertaining to medical experiments conducted in a prison in 1964. The scan is an inverted image: white, type-written text on a black background speckled with white dots and a white margin on the left side of the frame. The information presented includes the dates of these experiments, the University of Pennsylvania doctors who facilitated them, the number of inmates who participated in the experiments, and the amount that inmates were paid, ranging from one to fifteen dollars per study. Brief descriptions of each test is listed, including “Transplant Removal,” “Topical Caproic Acid Test (Environmental Chamber),” “Intradermal Injection of Dextrose Solution,” and “48-80 on inner lip.” At the bottom of the frame is a yellow subtitle, “they keeping giving me medicine that makes me sick.”

CL: Institutional critique can test the boundaries of the institution, but it’s not reparative. If it were, we’d be facing a very different museum landscape, considering that people have been working within this genre for a long time. I don’t know if museums will need to rebuild post-pandemic, but all the people they have fired will certainly have to. Maybe one thing that institutional critique can do is serve as evidence for movements that extend beyond the museum. The best review that Pre-Existing Condition has received is its citation in the #PoliceFreePenn demands. #PoliceFreePenn is an abolitionist assembly calling for the removal of the police from the Penn campus, the end to criminal background checks for prospective employees, and ending contracts with carceral corporations [including] Aramark, among other insistencies. It also demands that the university publicly apologize for the Holmesburg Prison experiments, which ran for 23 years and involved upwards of 80% of Holmesburg’s incarcerated population, as the first step in a reparations process for the Holmesburg experiment survivors.

MS: In addition to your artistic practice, you have also served as an advocate for the disabled and chronically ill community through your activism, both independently and as a part of the art collective and support network Canaries. Although Canaries gives you a chance to combine art and advocacy, have you found it necessary to separate art and activism in your independent work?

CL: I don’t really identify as an activist, which also doesn’t preclude my organizing in different ways with friends at different times to different ends. I mostly identify as an artist and a writer. The art world has a difficult time framing marginalized artists as artists. People tend to label marginalized artists as activists if they make work related to their social reality or the social reality of their communities. Cis white men make a lot of visible artwork about the interiority and exteriority of their lives, but no one thinks of that work as activism. I am invested in discourses on art and social movements, but it feels critically important that my artworks not be viewed as a proxy for activism.

Carolyn Lazard, Support System (for Park, Tina, and Bob), durational performance over the course of a day, from 9 am to 9 pm, 2016 [courtesy of the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York]

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: An assortment of flower bouquets in jars and vases are gathered together on top of a wooden desk. Behind the desk is a library wall of books and periodicals.

MS: There is a recent piece in SSENSE by Dana Kopel, [titled] “The Museum Does Not Exist,” that has been the topic of discussion in a period [when] some art workers see the recent pandemic-related museum closures as a time to reevaluate the relationships arts institutions have with their community amid crisis. It is very reminiscent of the introduction to your text “Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice,” where you discuss the “striking discord between an institution’s desire to represent marginalized communities and a total disinvestment from the actual survival of those communities.” With the way that COVID-19 has fully exposed so many of the fissures of the art world, do you think that there is an opportunity for arts institutions to reimagine access and equity from a disability justice perspective?

CL: Institutions already invest a lot of resources into access for nondisabled people. The accommodations that disabled people have always asked for are now available simply because nondisabled people need them. I don’t think COVID-19 has exposed fissures. These fissures have been glaringly obvious since arts institutions started to present themselves as institutions of social good. Disability Justice is a framework that expands beyond the rights and accommodations logic of disability rights. It is necessarily comprehensive because ableism is systemic and bound up with other systems of oppression like white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, and capitalism. Most arts institutions (as we understand them) would not survive being transformed in accordance with the principles of disability justice. They would become unrecognizable.

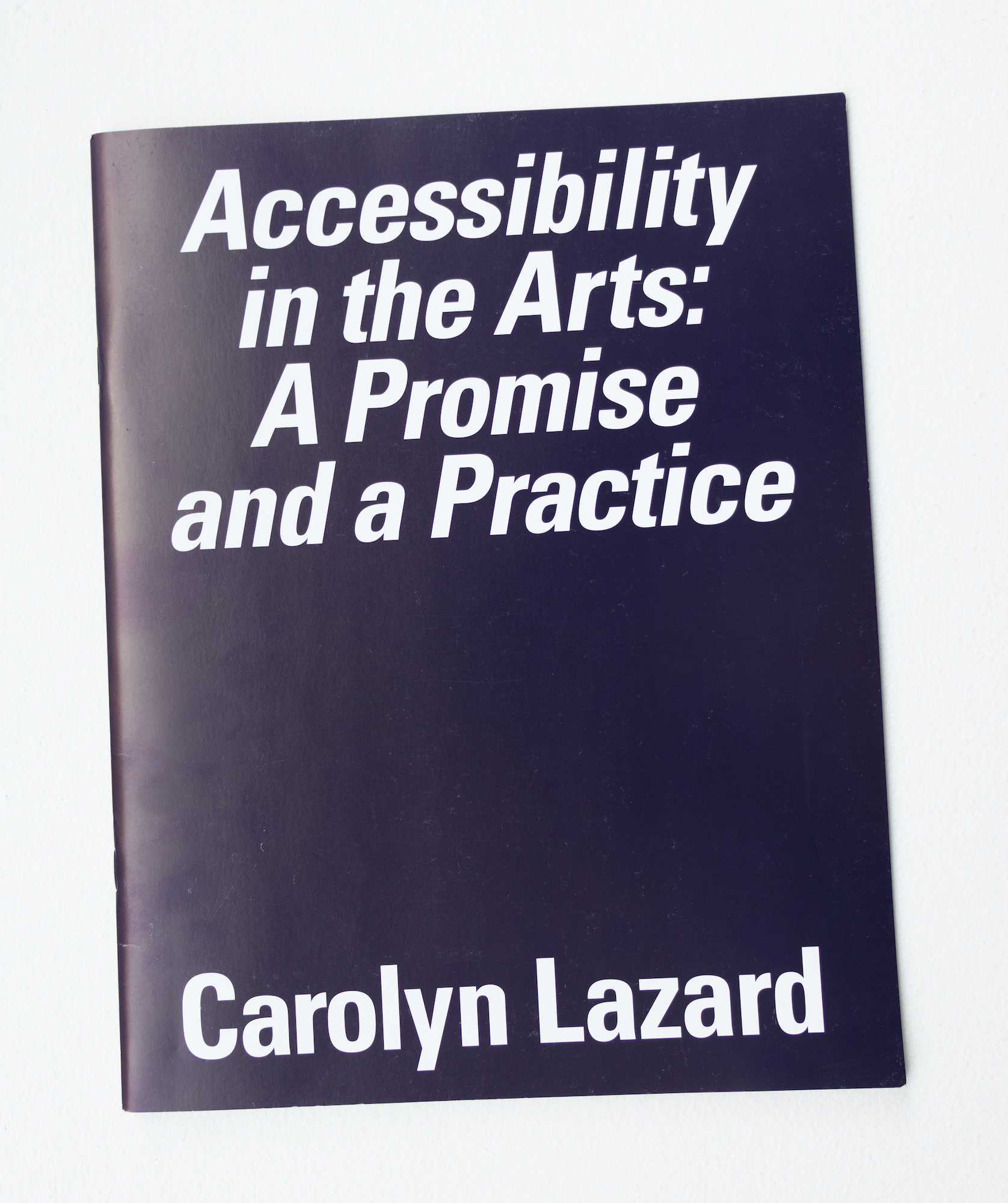

MS: I want to talk a bit more about “Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice,” because it’s such an instructive and detailed text. You include very concrete ideas on things that smaller arts spaces can do to be more inclusive of those [who have] disabilities through the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), such as services [including] closed captioning and Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) for d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing members of our community. But you also discuss how, within disability justice frameworks, ADA isn’t the end goal of accessibility, and these changes need to accompany a much more expansive way of considering equity for all. That’s a dichotomy … present in a lot of your work: the push-and-pull between lawful, concrete change and the much more difficult work that requires radically rethinking institutionality, inclusion, and selfhood. How do those ways of thinking about disability justice and representation work in tandem?

CL: Disability justice is a really expansive framework. Some accommodations are material, and some accommodations are social. The ADA is a really important piece of [legislation], but it hardly encompasses the needs of all disabled people in this country. The ADA was shaped by respectability politics: it didn’t address how people are disabled by state violence, by poverty, by the policing of the gender binary. The state requires that one’s disability be objectively measurable when so many people live with invisible disabilities, including people with visible disabilities. I don’t think of it as a dichotomy or even a spectrum. Disability is more like an infinitely expanding field of need and the joy, love, and care required to meet that need. It’s really beautiful, actually.

Carolyn Lazard, Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice, 2019, commissioned by Recess, edited by Kemi Adeyemi, designed by Rosen Tomov & Riley Hooker [courtesy of the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York]

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A dark purple publication with a slightly reflective cover against a white background. The cover reads: “Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice/Carolyn Lazard” in white text.

MS: Finally—and this may be a bit of a difficult subject to discuss, simply because we’re in the middle of it—I want to talk a bit about COVID-19 directly. Have you found that people are engaging with your work differently now that physical health is such a constant worry in ways that are completely foreign for most able-bodied people?

CL: I’m not super concerned with what nondisabled and/or non-Black people think of my work. And I’m even less concerned with the revelations of nondisabled and/or non-Black people during a time in which Black disabled people are being killed in droves by the racial eugenics of the healthcare system and the police. For Black disabled people, this crisis of care is a constant. It precedes the pandemic and will most likely continue after. It’s true that this moment makes clear how fragile abledness is and even how porous the line is between being disabled and being nondisabled. The temporarily nondisabled are grappling with a different life in which their access is severely restricted, maybe for the first time. There’s an attempt to engage discourses of care and dependency, but unfortunately it’s happening in the total absence of actual disabled people. We are the most vulnerable, and also the most knowledgeable, about how to survive the present circumstances.

The longer everyone else gets to go outside, the longer we have to stay inside. And disabled workers were sacrificed for the lives of the non-disabled. That’s the eugenic logic of “herd immunity.” That’s no different than life pre-pandemic. All we can do is turn toward each other to survive while “healthy” people temporarily manage their anxieties of an indeterminate future. We live in that future, here and together.

This exchange has been edited for publication.

***

Carolyn Lazard’s first solo exhibition, SYNC, opens on September 10, 2020 at Essex Street / Maxwell Graham in New York.

***

This interview originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.

Madeleine Seidel is an arts writer and Masters candidate at Hunter College. She has previously worked at the Whitney Museum of American Art and Atlanta Contemporary. Her current research interests include American feminist art movements in the 20th century, curatorial practices in film exhibition, and the art of the American South.