Cajsa von Zeipel: Nine Lives

Installation view, Cajsa von Zeipel, “Nine Lives,” 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York]

Share:

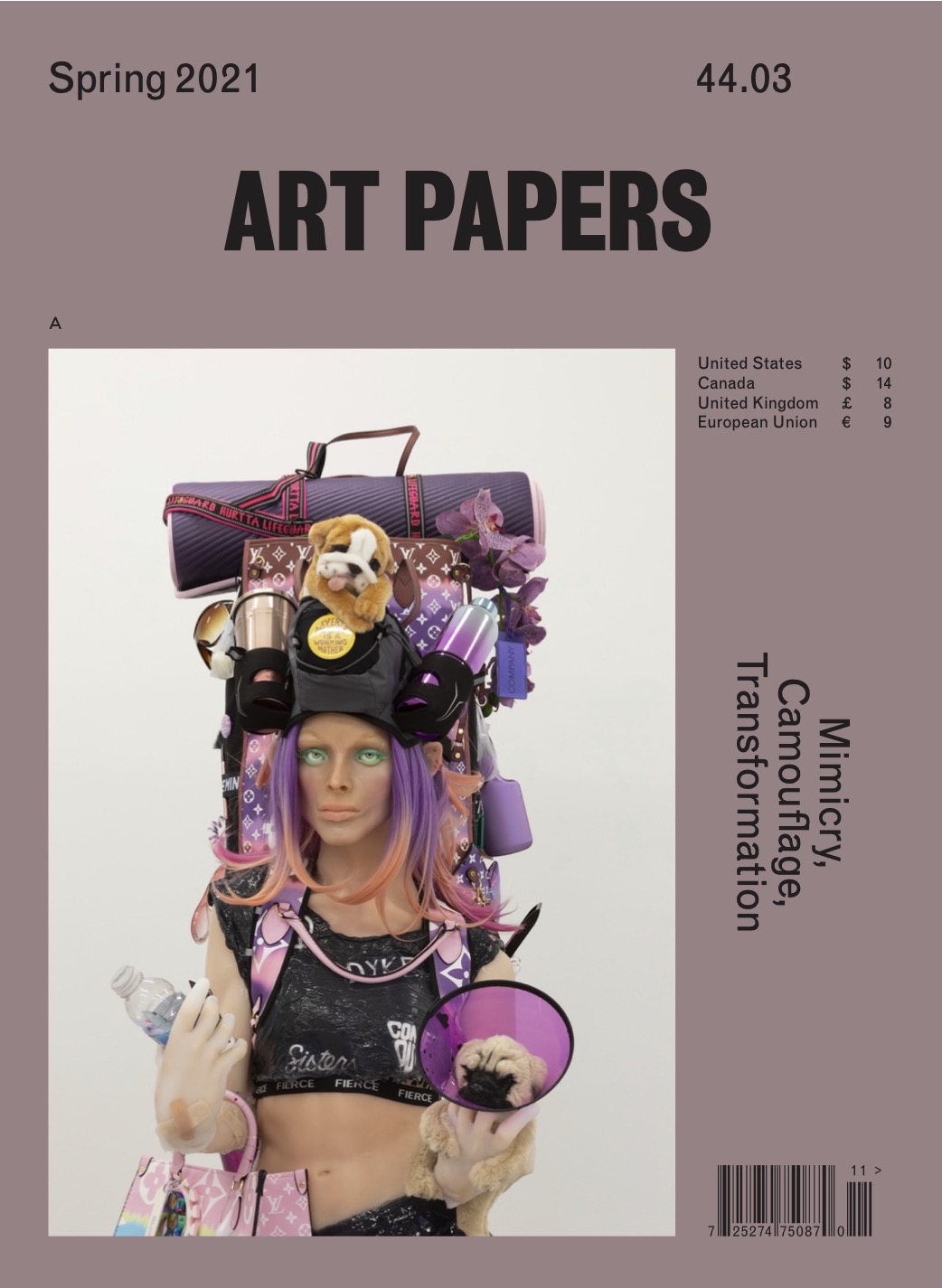

Nine Lives features sculptural tableaus that Cajsa von Zeipel populates with life-size silicone figures. Each figure is clothed in athleisure that is club-kid aspirational and, from all appearances, has been shopped online via algorithmically targeted ads. These advertisements, which have become so catered to users’ tastes that there is no need to wear a recognizable brand name any longer, allow one to become a brand through one’s own curation of things. The figures’ excessive adornment is dizzying but calculated, especially if you are familiar with social media culture. These figures embody store display racks as much as they do people. Von Zeipel plays with this duality by deploying a retail store’s clothing rack display to introduce the exhibition. A material accumulation here feels destined for the psychoanalysis of contemporary capitalistic consumption—of images as well as of things. Von Zeipel’s figures are too pale to be real—a product of their composition as silicone sculptures, and a situation of which they appear somehow aware. They are fashioned with the glossiness of self-made—or selfie-made—influencers. Their stares are too wide for a viewer to humanize the characters completely. They are cyborgian. They are human-object hybrids, not because they are sculptures but because of their poses. If these sculptures were real people, they would be living a life that is Insta-ready.

Installation view, Cajsa von Zeipel, “Nine Lives,” 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York]

Installation view, Cajsa von Zeipel, “Nine Lives,” 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York]

As you enter Cajsa von Zeipel’s Nine Lives, you’re greeted by a nameless installation in which she replicates the kind of unkempt situation that a shopper might find near the checkout line of a highly trafficked Nordstrom Rack. The items on the racks evoke the inventory of an airport convenience store, maximized for a certain type of femme: a dog-owning, jet-setting millennial. Many of the items on the racks are improperly shelved, thrown about as if they were almost purchased but lazily abandoned by an entitled patron. The collection of goods includes sport water bottles, multicolored hair extensions, baggage tags, fingernails, breast pumps, and science fiction novels. These objects serve as a physical glossary for what’s to come inside the main room of Company Gallery. Nine Lives relies on fashion to convey meaning via mimicry and brand spoofing.

Faint tire skid marks on the floor begin outside the glass gallery doors, in the lobby area of Company Gallery, and continue within, linking several artworks in the exhibition. These marks enhance in definition as they dance up and down the walls, defying physics. They spread in width and distort in ways that are reminiscent of a 3-D–modelling program’s vector warp. These marks end their journey at what appear to be Stella McCartney–style fashion-sneakers-of-the-future on a work titled Every Mother is A Working Mother. The figure in this sculpture is the implied producer of the skids, as if hurried on their journey from the airport, with neck pillow, yoga mat, and carry-on luggage in tow. The works in Nine Lives can be interpreted as caricatures of the gallery-goer: the type who flies in, is in a rush to see art exhibitions before a packed day of Starbucks-fueled encounters. The living gallery-goers are implicated, as we witness this exhibition, participating in the culture the artist is critiquing. Although Nine Lives could be dismissed as light-hearted cyberpunk fantasy, the exhibition—like William Gibson’s Neuromancer, which is present in one of the store display racks—is a dystopian version of reality, delivering a cutting critique of who we are, now.

Installation view, Cajsa von Zeipel, “Nine Lives,” 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York]

The works in Nine Lives build upon a vision of magnified but also queered White femininity. Von Zeipel’s figures feel like descendants of the Gen X “Tribeca Mom” or the “Park Slope Mom,” merged with their more rare younger sibling: the radical, rainbow-wig-wearing, Millennial influencer who has yet to invest in untraditional ways of replicating family. These types are a mostly White and upper-middle- to upper-class cohort of women who have been on the radar of the fashion world for the past decade, as celebrities and folks of means move into the Tribeca neighborhood of Manhattan or the Park Slope region of Brooklyn and populate them. But unlike the celebrities of Los Angeles, they live discreetly and effortlessly as they bounce from Equinox gyms to Whole Foods, with small dogs and babies in strollers, wearing one comfortable but expensive uniform “curated” for many scenarios throughout a hectic day. They blend with the masses, but their class positionality can be identified only by others in the cohort through the straps that bind their luggage, the baby stroller they push, or the subtle details on their handbags. As the figure in Friends with Grapefruit eats a hearty and leafy sandwich, the sandwich registers as organic AF and is therefore charged with class politics.

There are many items that bind: leashes, lanyards, tags. Other binding apparatus take source inspiration from BDSM suspension and aerial fitness classes, subcultures that have become increasingly appropriated and made mainstream. Most bodies in the exhibition are bound together by products. The Tribeca/Park Slope Mom is defined by her activities, the status-symbol tech brands she uses, and her similarly abled and monied associates. The products adorning von Zeipel’s sculptures may be the only thing holding them together—as with a friendship, relationship, or greater polity. This flimsy yoke makes them grating, unsympathetic caricatures. What redeems them is the way the artist repositions them as the viewer, in contrast with the viewer, and to each other. If these figures are meant to embody the Millennial version, as opposed to the Gen X class, we may never know what they do for employment. The influencer just is, and documents it.

Installation view, Cajsa von Zeipel, “Nine Lives,” 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York]

Installation view, Cajsa von Zeipel, “Nine Lives,” 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York]

The clothing of Von Zeipel’s characters mimics the high-fashion version, and there could be a class slippage at play where everything is borrowed for the sake of the photo shoot. Von Zeipel’s figures take inspiration from the same people, or similar ones. The sculptures are mostly femme, though sometimes they present—or are fashioned—androgynously or as genderqueer, particularly when the figure in Friends With Grapefruit has breasts that are held up by a body suit so seamless that it takes a second glance to recognize that it is wearing a skin suit. It consists of two body types merged into one. I think about what queer feminist scholar Sara Ahmed writes in her 2006 book Queer Phenomenology on orientation with regard to sexualized bodies: “If the sexual involves the contingency of bodies coming into contact with other bodies, the sexual disorientation slides quickly into social disorientation, as a disorientation in how things are arranged. The effects are indeed uncanny; what is familiar, what is passed over in its veil of familiarity becomes rather strange.” This strangeness is felt when the viewer recognizes the poeticism of the skin suit in Friends With Grapefruit. In the work Catch and Kill, it could be difficult to discern that two bodies are suspended. A viewer might mistake them for a lone, broken, or alien one. As the two figures in Catch and Kill play with each other and spill a cup of Starbucks coffee, their activity is sexualized but the position and reason of their bodies intertwining is indecipherable.

Two of von Zeipel’s works in Nine Lives are bound together in additional matter by a clear goop that is sexually suggestive as ejaculate when figures are posed as if engaging in sexual activities but simultaneously inspired by the coolant gels and liquids from technological hardware. Considering an obvious influence by cyberpunk science fiction, this goop also invokes something alien and other-worldly. The goop is materially adjacent to the silicone that von Zeipel constructs the bodies of her figures, but it plays a different role when it is slathered and dripping over the bodies and clothes.

Von Zeipel’s goop binds clothes to bodies and figures to each other, collecting into icicles but also creating the appearance of people and clothes melting and morphing. A folded stack of one hundred dollar bills is stuck to the foot of Every Mother is A Working Mother thanks to this goop. I interpret this goop as a physical manifestation of the internet, embalming everything and transplanting the exhibition into the space of a social media platform rather than the street. This goop is like a melting computer window or interface that thinly veils and produces new meaning. The goop flattens the materiality of things that have different tactile characteristics and turns individual objects into a collective body or collective understanding of excess.

Installation view, Cajsa von Zeipel, “Nine Lives,” 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York]

The accumulation of gendered and racialized stuff in von Zeipel’s work evokes a variant of man-spreading that I will call “White-spreading,” a phenomenon present and critiqued in von Zeipel’s Nine Lives. White-spreading has been described by Black people and people of color in America as White people’s refusal to make room for them in public space; and as the ways White people take up space in public through use of their pets to extend White bodies. It is an acknowledged microaggression. The figures in von Zeipel’s artworks, with their massive luggage and employment of screen and phone mounts and baby strollers extend her figures into space in an aggressive manner and demand this space for a different reason. What she seeks to loudly impinge upon through her artwork is a heteropatriarchal understanding of society. This spreading within is justified because it is employed as a critique, a recalculation of who gets to be represented, and how.

Goop becomes the medium to deliver von Zeipel’s message, which is not a simple celebration of capitalistic excess.

***

This review originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Spring 2021 // Mimicry, Camouflage, Transformation.

Caitlin Cherry draws on painting, sculpture, and installation in her multifaceted practice to coalesce work into articulate and alluring representations of Black femininity. Filtering these media through layers of digital manipulation, her work draws parallels between Black femme bodies, frequently commodified and positioned as sexual assets, and the seductiveness of art objects in the commercial gallery circuit. Cherry is currently assistant professor of painting and printmaking at Virginia Commonwealth University and founder of the new online program Dark Study, a contra-institutional space for radical learning about art and theory. Her paintings have been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, Performance Space New York, and The Studio Museum in Harlem, among other institutions. She has received a Leonore Annenberg Fellowship, and has been a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Artist-in-Residence.