BREYER P-ORRIDGE: We Are But One

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation detail, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

Share:

In We Are But One [April 15–July 10, 2022]—the first major, posthumous US exhibition of artists, musicians, occultists, and spouses Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (1950–2020) and Lady Jaye Breyer P-Orridge (1969–2007)—raspy, drawn-out synths bleeding from not yet visible videos flood the space and immerse the body in an eerily familiar lull. The sound inspires the sense of calm that can ensue upon stepping into a place of worship—out of curiosity or to seek respite. Curated by the artists’ friend and gallerist Benjamin Tischer at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn, NY, We Are But One successfully presents an eye-opening glimpse into the artists’ nearly 20-year-long life-project, The Pandrogyne, through sculpture; collage; archival footage; works never before shown publicly; and a new sculptural tribute by Genesis’s daughter, Genesse P-Orridge.

The Pandrogyne project was officially christened on Valentine’s Day in 2003, when, as a mutual 10th-anniversary present, the lovers underwent the first in a series of surgical procedures to transform their bodies to increasingly resemble each other. They aimed to break down and rebuild their consciously and unconsciously conditioned preferences and aesthetics. The Pandrogyne project is an expression of their desire to override and defy the conditions stipulated on their bodies and beings by the evolutionary parasite that is DNA—as it is described in the Pandrogeny Manifesto. But much more than a physical transformation, the project is also an expression of their love—a love so chivalrous and deep that it subsumed their separate bodies, individualities, and egos into a third, unified “pandrogynous” entity named Breyer P-Orridge.

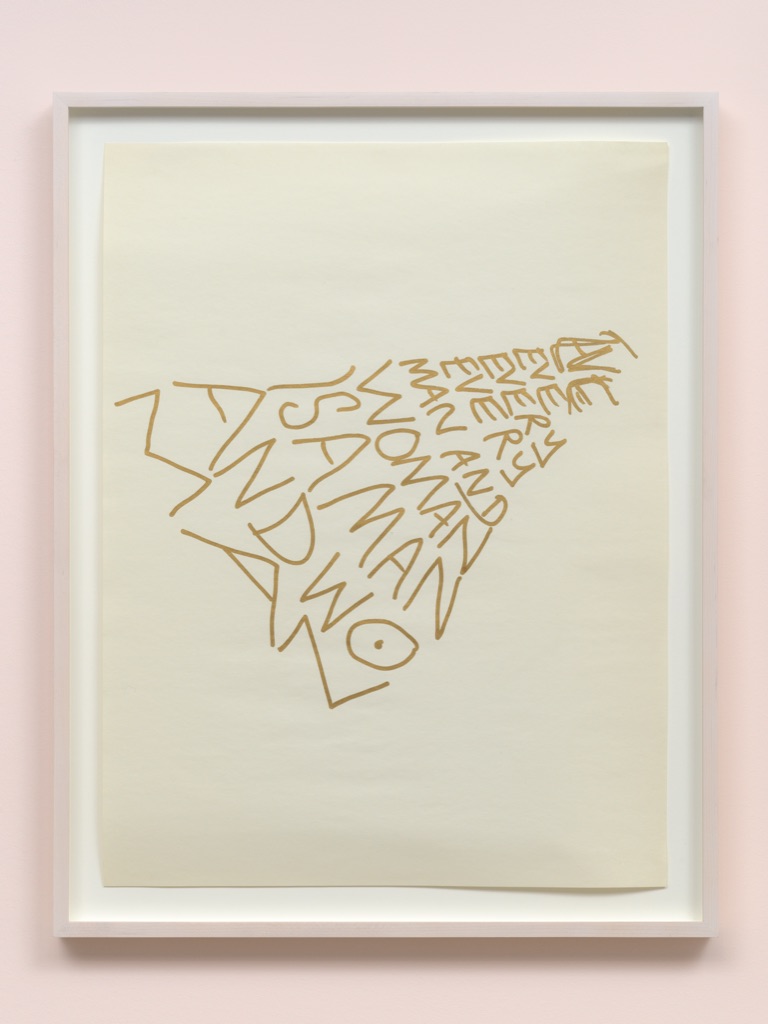

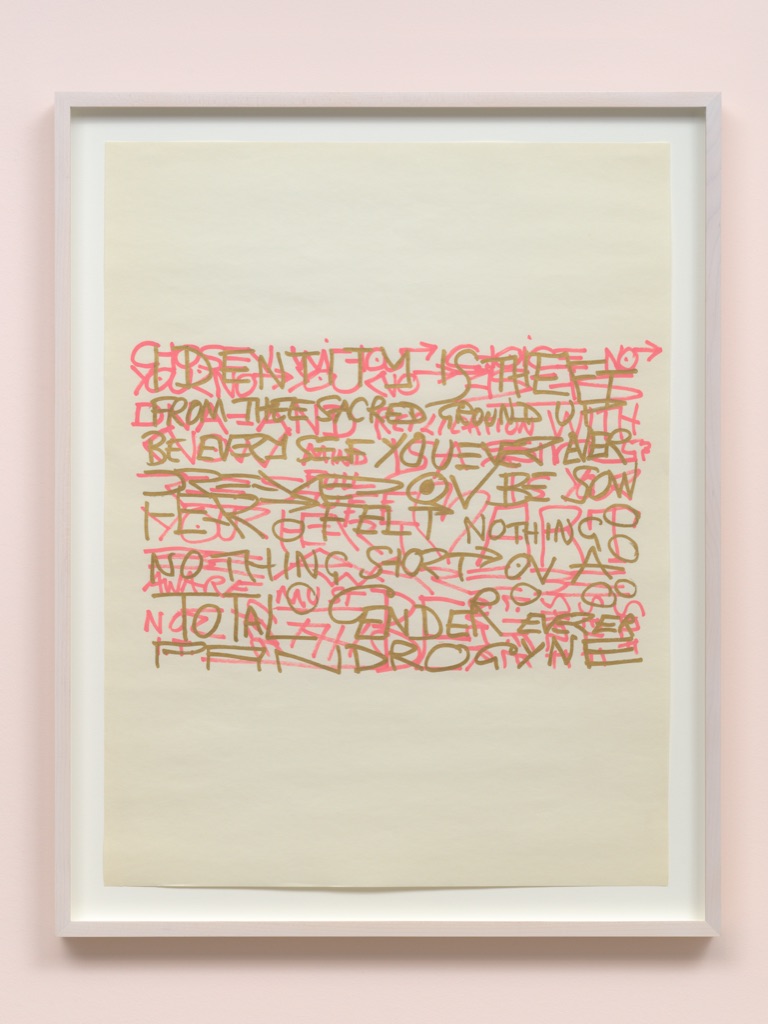

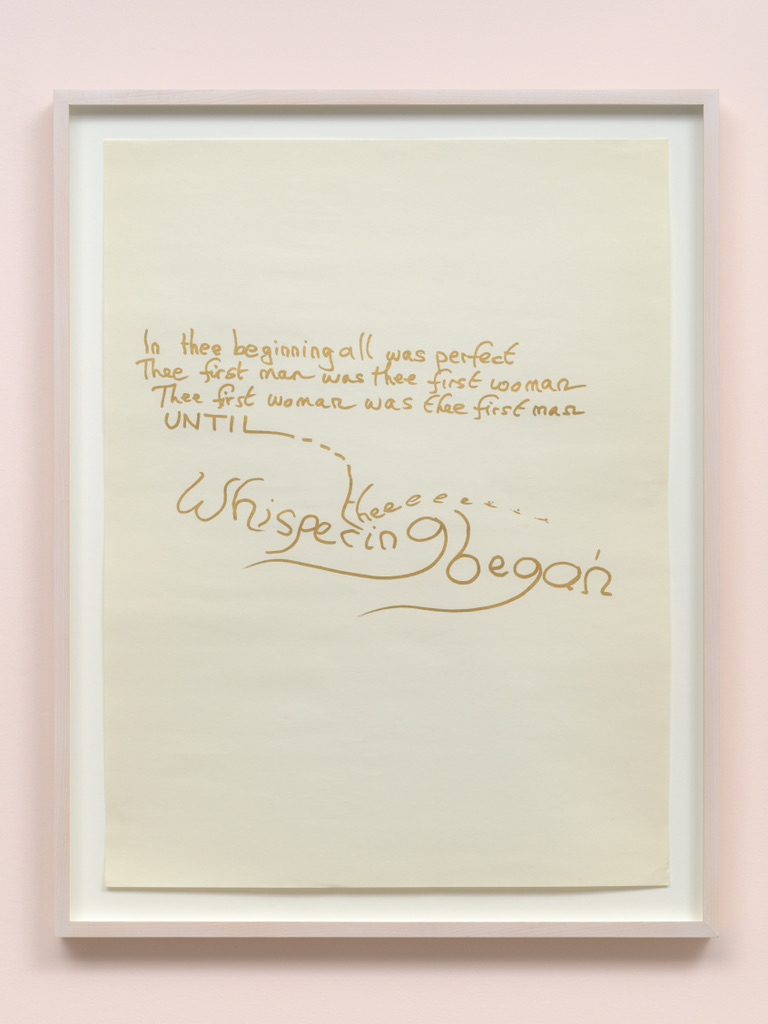

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation detail, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation detail, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation detail, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

A bronze-cast sculpture of the hand and forearm of industrial music pioneer Genesis Breyer P-Orridge extends in a gesture inviting a handshake, as if welcoming the exhibition’s visitors to connect. Touching of Hands (2016)—which was cast by artist Sarah Sitkin; engraved by tattooist Daniel Albrigo; and whose title is borrowed from a quote by multidisciplinary artist, writer, and poet Brion Gysin—performs two of Breyer P-Orridge’s core beliefs: that, to truly learn and be influenced by someone, one must spend time in their physical company; and that it is the artist’s duty to name their influences, and pass that attained knowledge on to the rest of the world.

Gysin’s impact upon Breyer P-Orridge runs across the exhibition, like a jagged throughline. Specifically present is the influence of Gysin’s cut-up method, which he popularized alongside his friend and collaborator William S. Burroughs—who used it to write his iconic 1959 novel, Naked Lunch. Whereas, originally, the method described the technique of physically cutting apart and rearranging text to create new meaning, Breyer P-Orridge expanded its application to their multidisciplinary art making, identity, and behavior.

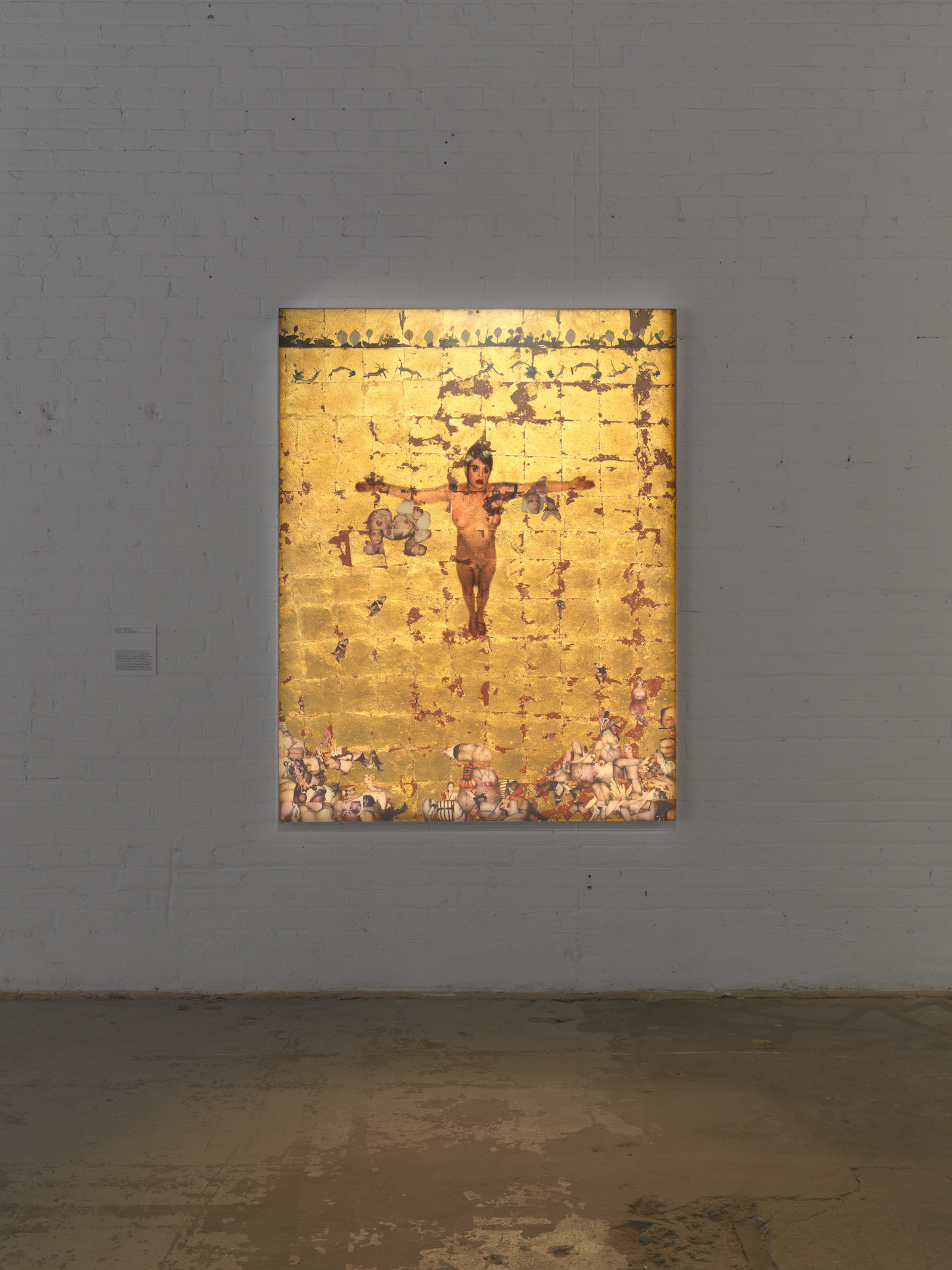

Hanging high and holy beside the bronze-cast arm is Transgen Sacredheart (2004), a print of Jesus, enlarged from a prayer card and mounted on Plexiglas. A photograph of Genesis’ chest, fresh out of he/r first surgery, is seamlessly blended into the image to bestow upon the figure a pair of divine tits and a surgical drain in place of a sacred heart. Warm spotlighting maps the border of the print so that it appears to glow from within. All the mounted prints and framed works on paper in the exhibition are illuminated similarly, invoking Breyer P-Orridge’s presence into the space in angelic gold. More than “a pun and uncanny combination,” as the wall text describes it, Transgen Sacredheart brings queer body modification and transness into conversation with what society normatively defines as sacred, while doubly serving as a big fuck-you to those same oppressive norms.

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation detail, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation detail, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

A Roman Catholic kitsch aesthetic, similar to that of the prayer card, is echoed nearby in the golden custom frames that surround Stations ov thee Cross (2003), a series of 12 photographic prints hanging flush against one another in two vertical columns of six. Each photograph depicts an “after” image of a surgical procedure performed on Lady Jaye and Genesis. They are shown side by side, facing each other, documenting their commitment to “becoming two parts of one new being that exists more fully when … physically together.”

Sticking out in stark aesthetic contrast to the rest of the work in the exhibition is a recent installation: a huge, domed, temple-like structure titled Altared State (2022). The structure was conceptualized by Genesse—who now manages Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’s estate—and was fabricated in collaboration with Pioneer Works. The dome and its foundation blocks are constructed from grainy, untreated plywood that has been torched and sooted by Genesse. Laser-cutout holes surround a dome crowned by the Psychick Cross, the symbol of the Temple ov Psychick Youth, which Genesis co-founded in 1981 as an anti-cult dedicated to “changing society through the magical transformation of individuals.” If one peers inside, the installation reveals itself as a tender shrine, containing framed family photographs and sacred artifacts, such as Genesis’s gold teeth. At its heart stands what may be the exhibition’s most sacred artifact of all: the talismanic Blood Bunny, a wooden rabbit figurine whose porous surface is stained with blood, a record of more than 1,000 intravenous ketamine trips that Genesis and Lady Jaye took together.

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation view, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

Also on view is a projection of the newly unearthed one-hour video, Thee Whispering Began (2003), which was conceived with, and filmed by, Breyer P-Orridge’s longtime collaborator, artist Sam Zimmerman, who designed video projections for Genesis’ cult rock band, Psychic TV. The video documents the hands of Lady Jaye and Genesis taking turns overlaying words and phrases, and playing with language by using pink and gold markers on sheets of paper. The result is a suite of 18 scribbly, prophetic drawings that hang in two equal rows of nine, on either side of the projection. A phrase written in one of the framed drawings, “There is no reason on earth why you should run out of people to be,” lingers in my mind.

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation view, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

Upon circling back to the iconic Jesus—who slayed for our sins—the source of the entrancing, brassy notes echoing through the space is revealed. Visible on the far side of a black curtain, a room is set up as a chapel, complete with church-pew seating, and is illuminated by a white, neon rendition of the Psychick Cross on one side, and by a video projection on the other. In this chapel—where no thoughts are preached, only shared—the artists get to speak for themselves in a looping, hourlong-plus playlist incorporating outtakes, interview footage, a performance of the Pandrogeny Manifesto, and more video collaborations. In this room we learn—and I take with a large grain of salt—the integral role that Genesis’ spiritual visits to Kathmandu played, in he/r practice and in the conception of Breyer P-Orridge.

BREYER P-ORRIDGE, We Are But One, installation view, 2022 [photo by Dan Bradica; courtesy of Pioneer Works, Red Hook]

There is a thin line between inspiration and co-option, which the trope of the White Westerner’s quest to the Far East in search of meaning unfortunately crosses. However—in line with Pandrogeny’s ethos—in the same way that two becoming one doesn’t erase each individual, but instead unifies them, the post-colonial ickiness that tinges some of the work in the show should not overshadow the whole, or its aims. Ultimately, the Pandrogyne project is about bringing the world together and uniting us all in love. It’s about cutting up the ends of the linear spectrum of being and reconnecting it so that there is no more black and white, blue or pink, only a divine, gray circle. For that, and much more, Breyer P-Orridge’s legacy of love is something we could truly learn from.

Isis Awad is a curator, writer, and poet based in New York. She is the founding director of Executive Care*, an art organization at the service of Black trans and queer artists, and of artists of color, from performance and nightlife communities.