Boy With Luv

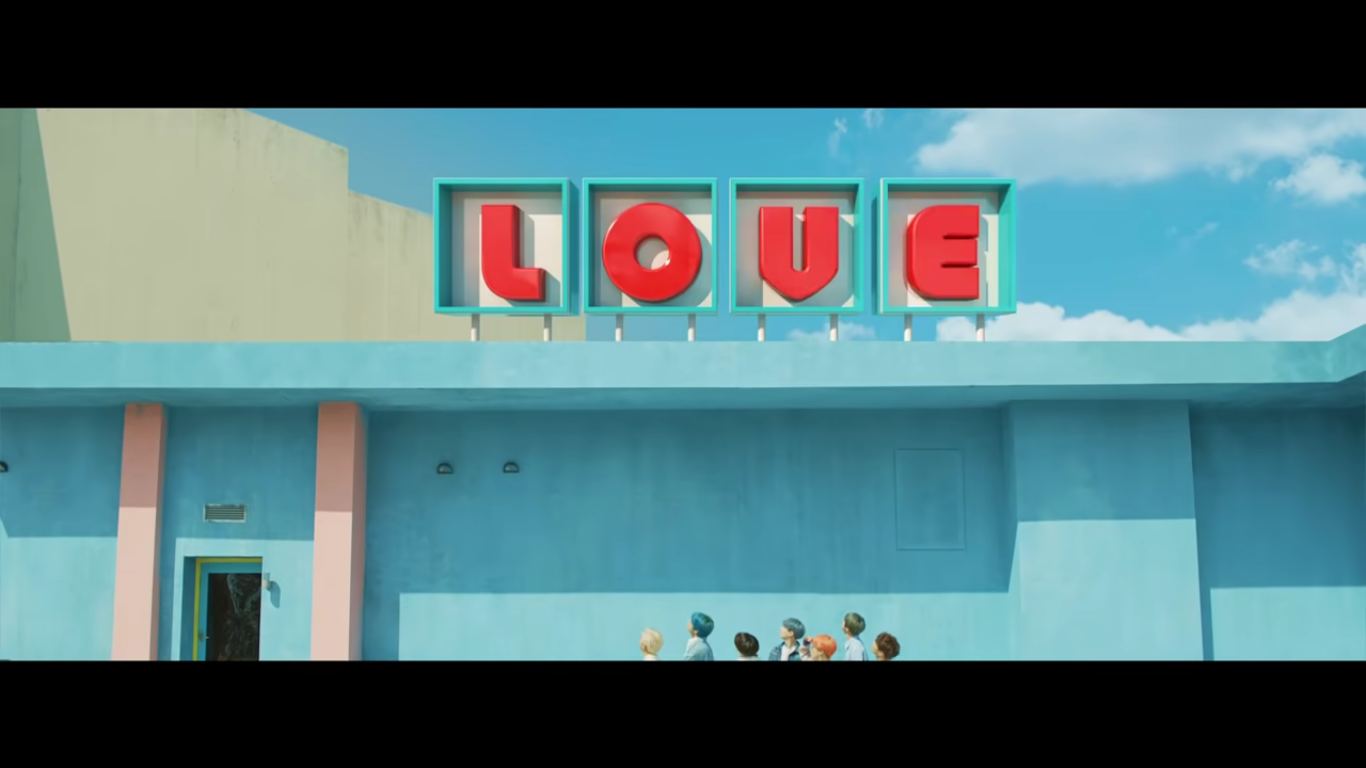

BTS (방탄소년단) ‘작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv) (feat. Halsey)’ Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

Share:

I successfully spent most of my late twenties avoiding a direct engagement with the gradual, and ongoing, cultural takeover of South Korea’s BTS. I was peripherally aware of the K-pop septet through the suggestion algorithm on YouTube, where I would see all the members huddled together, struggling to contain themselves within the confines of a thumbnail frame. There were also the Twitter hashtag trends that resulted in a seemingly infinite scroll of BTS gifs, the TikTok dance challenges, the BuzzFeed quizzes, the award show performances, and the frequent media coverage. I knew there were more members than I considered necessary for a successful boy band—the American groups that dominated the charts during my childhood averaged around five boys each—and I knew the worldwide fanbase identified themselves as ARMY, an acronym for Adorable Representative MC for Youth. Until recently, I couldn’t name a BTS song. What was it about this group, consisting of V, J-Hope, RM, Jin, Jimin, Jungkook, and Suga, that repelled my gaze? Why was I so determined not to succumb to the exhilarating brightness of the music, the highly skilled, synchronized footwork, the elaborate world-building of the music videos, and the bounce of the glossy Pantone-colored hair?

Growing up in the Philippines, a country colonized by the United States from 1898 until 1946, I was conditioned to idolize the US and all its cultural exports—Neutrogena face wash, Cap’n Crunch, Captain Planet, Bratz dolls, and O-Town. Subscribing to Americana meant drinking Mountain Dew after soccer practice and succumbing to the semi-permanent fluorescent orange dust stain of Cheetos, consumed instead of the equally satisfying, locally made Clover Chips. It also meant MTV (the late 1990s and early 2000s version) and its constant stream of music videos. I was inundated with music, but more so with the people who performed it. I would beg my mother to buy copies of imported Teen People, Bop, or J-14 magazines so I could tear out the centerfold posters and tape them to my walls. My room was plastered with the likes of Justin Timberlake and his head of uncooked ramen; the brothers Hanson and their shoulder-length, caramel hair; a young, pre-Newlyweds Nick Lachey; and a Millennium-epoch Backstreet Boys. When I was a teenager, the homogeneous nature of my pop music interests didn’t seem significant, but it’s evident now that a specific brand of masculinity had migrated through the United States’ imperial and military hold on my country. It was usually White, with fairly well-developed muscles and heteronormative desires, wearing oversized sports jerseys, cargo pants, and denim jackets.

*NSYNC – “Bye Bye Bye,” Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

*NSYNC – “Bye Bye Bye,” Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

This masculinity was further embedded and reproduced in the music videos I spent most afternoons watching. The men in these videos represented an adamantly heterosexual and cisgender masculinity, despite the personal identifications of some of the performers. The music video plots rarely strayed from the broad, recurring theme of lusting after—or escaping the vengeance of—a tall, slim, hyper-feminized woman. Even simpler than the narratives was the choreography, which was often just an assemblage of the band members standing shoulder to shoulder, or in triangle formation, facing the camera. As if fulfilling some divine obligation, the industry-standard crotch-grab always made an appearance. But mostly they shifted their weight from one side to the other while bringing a clenched hand to their chest or sweeping it out and away from the body with palms open and fingers extended. Occasionally, they would hop from the left foot to the right or pump their fists in the air—a precursor to the Gehenna of Jersey Shore. There was a perceptible stiffness to these attempts at corporeal expression, restrained as they were by a set of social indicators.

My fondness for music videos grew out of the medium’s use of a song’s temporal limits to create fictional spaces and identities. But this genre’s world-building was more simulacrum than speculation. The boy band members would shoot hoops at basketball courts, fake-laugh in locker rooms, and convene at airport terminals and tarmacs, clubs and carparks—surrounded by a crowd of attractive women. The members were portrayed as buddies, pals, friends—the dude-bros of middle school and high school. There was nothing challenging about them, aside from debates over whether this or that boy band was better, because apparently you could not like both. They were successful beyond all measure.

In my college years, my fascination with boy bands swelled beyond the chart toppers of North America. I found myself caught in the tide of the most significant boy bands of early-2010s K-pop: BIGBANG and 2PM. I would spend hours on YouTube watching snippets of translated interviews and appearances on variety and reality shows, had downloaded wallpaper for my phone featuring my favorite members, and would rewatch their music videos on a loop. Some were extremely elaborate. In a single video, the set design could oscillate between a neon pink, post-apocalyptic disco; an ancient pyramid, doubling as a military base, with cannons protruding from the tip; and an extravagant, LED-lit, mirror-filled club. The costumes followed this shift toward utmost pageantry. Whereas band members of the previous generation might have been styled in torn jeans, slogan T-shirts, slanted flat caps, and tank tops, the videos from this era reflect a decorative turn in the bands’ appearances. Hairstyles began incorporating bold colors and cuts with long extensions and exaggerated blow-outs. Wardrobes combined turquoise fur coats, cowboy outfits, spacesuits, and ornamented shoulder pads. But I wasn’t watching for the embellished garments and imagined spaces. I watched because these bands radiated a variation of the masculinity I idolized in my youth.

BIGBANG 뱅뱅뱅 (BANG BANG BANG) Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

Imagery from the music videos of this particular moment in K-pop’s boy band wave reeked of objectification and hyper-sexualization. Men and boys were often shirtless, oiled up, and flexing; their chests smeared with dirt as if it were a stamp of authentication. Tight leather pants were worn low on the hips while the performers danced on expensive, silver-rimmed cars, heavy metal chains swinging from their necks. Fragments of the performances bore an uncanny resemblance to the music video for D’Angelo’s “Untitled (How Does It Feel),” which catalyzed the objectification of a man who unwillingly became, after the video’s release, more recognized for his sexual appeal than for his vocal ability.

The video’s concept was simple: D’Angelo, adorned only with a gold crucifix necklace and a single bracelet, stands in front of a plain black backdrop. Strong chiaroscuro lighting emphasizes his chiseled chest, pronounced abdominal muscles, and tattooed arms. As the song progresses toward its climax, the camera deliberately and slowly tilts down D’Angelo’s stomach, fixated on the beads of sweat that trickle toward his ilia. The aesthetic objectification of D’Angelo’s glistening, muscled upper body participates in a familiar American stereotype, one that has classified Black men as hypersexual, as object, and as predator; removed from personhood. It’s a stereotype which has been crafted and refined by the White ruling class of the US, mobilized by their governing bodies, and used to justify centuries of slavery and the continued inhumane and abhorrent treatment of Black men by the state.

BIGBANG FANTASTIC BABY Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

BIGBANG FANTASTIC BABY Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

Witnessing BIGBANG and 2PM absorb this damaging stereotype and incorporate it into their music videos destabilized my libidinal gaze, although it wasn’t unusual to see the appropriated aesthetics of Black American culture and related racial stereotypes flicker throughout K-pop’s imagery. The genre has long been criticized for its Black cultural mimesis, deployed in exchange for mass-market relevance. Many bands have been deliberately manufactured to imitate the most successful Black performers of the 20th and 21st centuries. K-pop artists can be seen with their hair in cornrows and dreadlocks. In their videos, glistening lowriders with gleaming chrome grills ski and jump on souped-up hydraulics. Their lyrics are littered with the nonchalant use of African American Vernacular English, and the actions and stylings of Black artists are persistently reproduced. BIGBANG and 2PM’s inability to exclude this habit from their creative output contaminated the pedestal on which I placed their music. But perhaps their co-optation could be interpreted through another lens. It could be said that BIGBANG and 2PM were attempting to employ one destructive stereotype to reject another—that of the de-sexualized, feminized Asian male.

When BTS first began infiltrating my consciousness, I was hesitant to acknowledge their cultural impact. I had lingering misgivings about K-pop’s recurring Black cultural appropriation and misrepresentation, but what really troubled me about BTS was that they seemed to reinforce the very stereotype that BIGBANG and 2PM had attempted to renounce. Each BTS member’s skin was luminous, pearl-like in its glow; their lips gleamed with a streak of deep-coral lipstick; they emanated an aura that was soft and gentle, almost celestial in disposition. They were, well, beautiful. And this beauty forced me to confront a painful American narrative that has framed the Asian American male population as effeminate and weak.

BTS (방탄소년단) ‘작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv) (feat. Halsey)’ Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

In the late 1850s one of the first mass migrations of Asian populations to the West occurred during the California Gold Rush and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. A wave of Chinese laborers, mostly men, relocated to the United States in the hopes of making enough money to send back to their families in China. Corporations favored the migrant Chinese worker, as they would work for low wages and in bad conditions. As a result, the White working class became largely hostile to the newly-arrived Asian migrants. Threatened by the possibility of losing jobs—an anti-immigration myth that continues to permeate our contemporary moment—White, working class men refused to allow Chinese laborers access to White-majority factory production jobs, forcing them instead into industries considered feminine for their domesticity. Chinese American men began to work as cooks, laundrymen, waiters, and dishwashers. White resentment evolved into the institutional violence of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act—the first US law to bar entry for an entire nation of people. Anti-Asian propaganda gave us the fear-mongering image of “Yellow Peril” and the labeling of Chinese male laborers as “coolies”—machine-like, sexless, and not-quite-human. This notion was still operative, 100 years later, in the caricatured name, social ineptitude, and heavily accented English of Long Duk Dong, a character in the movie Sixteen Candles (1984), whose submissive behavior with his female love interest provides the substance for many of the jokes. Presently, the old bigotry flares up in references to the “Chinese virus,” in anti-Asian brutality, and in an insistence on villainizing cultural and ideological imports from Asian countries. Much as with stereotypes of Black masculinity, perceptions of Asian masculinity were superficially molded out of White fear to sit in contrast to, while simultaneously valorizing, an idealized White counterpart.

As backlash against toxic masculinity ruptured the United States’ sociopolitical landscape in the latter half of the 2010s, I felt that my bias toward BTS was foreclosing an alternate vision of masculinity and passing over the work done by the LGBTQ community to collapse the dichotomy between normative gender roles. So, finally, I decided to watch one of BTS’ music videos.

BTS (방탄소년단) ‘작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv) (feat. Halsey) Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

BTS (방탄소년단) ‘작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv) (feat. Halsey) Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

Like a late-night trip to McDonalds when you’re far from home, I opted for the comfort that comes with familiarity, and chose a song featuring Halsey, an American recording artist. The title of the track is “작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv).” The Korean can be roughly translated as “A Poem for Small Things.” The video has more than one billion views. It opens with a springy bass line, reverberating softly through a staccato of buoyant synth chords and undergirding a muted, melodic vocable. The colors seem plucked from a David Hockney painting: Tangerine, peach, and mint green. A cinema, inspired by the long vertical lines and curved corners of the late 1920s and early 1930s streamline architecture, stands against a pool-blue sky. Perched on the cinema’s awning, a large, scripted sign reads Persona—a nod to the title of the group’s 2019 album.

A slow tilt of the camera reveals BTS’ seven members standing in two rows. They all wear some variation of a fuchsia, salmon, or white jacket, top, and pant combo—just one of the many outfit themes that will feature in the video, which also includes washed denim jeans and sweaters, feathered blouses, and tailored suits. From afar, their initial ensembles remind me of the silky, high-end pajamas that celebrities pair with their finest jewels when doing a “Get Ready with Me” video for Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar.

Their hair colors are varied in hue and saturation, as if chosen at random from a gradated color wheel. Their necks, wrists, ears, and fingers are adorned with rings, chains, and earrings—some more extravagant in their shine than others. A white flower wraps around V’s (Kim Tae-hyung) index finger; J-Hope (Jung Ho-seok) is embellished with silver chains and a single turquoise ring; Jimin’s (Park Ji-min) fingers are bejeweled with blocky gunmetal bands; Jin (Kim Seok-jin) wears a Chanel chain around his neck; and RM (Kim Nam-joon), Jungkook (Jeon Jung-kook), and Suga (Min Yoon-gi) opt for a set of hoops in argent or gold. All their lips glitter with a single swipe of bright strawberry gloss.

BTS (방탄소년단) ‘작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv) (feat. Halsey) Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

BTS (방탄소년단) ‘작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv) (feat. Halsey) Official Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

Shoulders shimmy as their bodies weave fluidly through choreography that melds hip-hop, tap, waacking, and contemporary dance. They spin and jump their way through a set that undergoes a range of transformations, transporting them to dreamlike topographies as the song progresses. Familiar environments, such as 1950s roadside diners with window booths, are made curious with a sunken dance floor taking up most of the center space. Streetlamps recalling Chris Burden’s installation at LACMA flash neon pink, set against a magnified large-stroke impressionist painting of New York’s skyline at night, which itself is similar to the canvasses you might find at vendors on the sidewalks outside the city’s art museums.

The once-blue sky morphs into a swirled storm of pinks, purples, and oranges, like a section of Xu Zhen’s luscious globs of pigmented paint in Under Heaven (2015), or frosting on a decadent cake. One of the final scenes finds the members illuminated by the glow of neon signs and Dan Flavin-esque light structures. References to BTS’ past albums and songs hang alongside their current modus vivendi—a miniature Fremont Street, instead of promoting $20 super-sized alcoholic slushies, fosters a message of Love with a capital L.

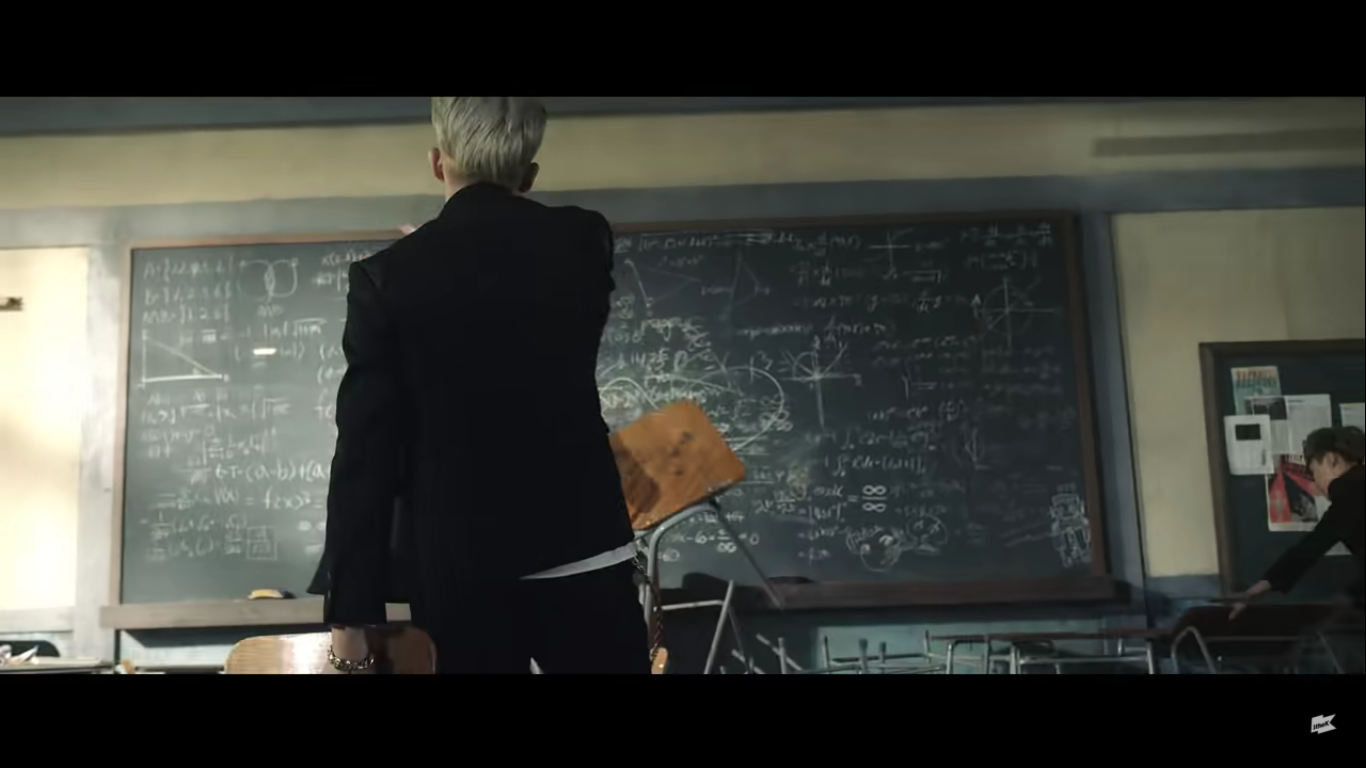

“Boy with Luv” starkly contrasts their 2014 hit of a similar name, “Boy in Luv,” a mashup of punk and hip hop. Plenty of growls, chest-beating, and eyebrow furls pepper the video with aggressive undertones. Electric guitar riffs tremble and jolt as a heavy bass drum pulses along; a turntable scratches and a motorcycle engine revs as vocals are layered in a chaotic and disorderly manner. Each member in “Boy in Luv” raps with an accusatory inflection, the corner of their lips snarled in demonstration of their virility. The video takes place in a neglected school—primarily in a poorly-lit classroom cleared of its chairs and desks by Suga, who throws them against a paint-chipped wall in frustration. As the members run up and down the school’s hallways, they each forcefully attempt to gain the attention of a slim, feminine young woman/girl, a trope familiar from the American boy bands of my teenage years. While “Boy with Luv” doesn’t forego the feminine presence entirely, Halsey’s position within the video is far from that of a romantic interest. The singer is not lauded or lusted after, and the boys aren’t posturing a masculinized version of themselves that is fixed in libidinal desire and American machismo. From “Boy In Luv” to “Boy with Luv,” one can witness BTS’ progression, from replicating the visuals and ideology of a masculinity reliant upon validation from an external source to embracing a presentation of happiness through understanding and self-acceptance.

BTS(방탄소년단) Boy In Luv(상남자) Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

BTS(방탄소년단) Boy In Luv(상남자) Music Video (screenshot) [courtesy of Youtube]

The group’s Korean name, 방탄소년단, translates as “Bulletproof Boy Scouts,” and they are also known as the Bangtan Boys. BTS recently revealed they would be taking on Beyond The Scene as an additional variation—a fitting name for a group that continues to redefine the various embodiments of the boy band. Porous and slippery, their shifting identities, music, visuals, and representations are precisely why I’ve suddenly found myself tapping my feet and rolling my body to “Boy with Luv.” I ship, and have a bias, and stan. I also mimic the choreography, poorly lip-sync the lyrics, and willfully allow their proposal of an unwavering love of the self to ripple throughout my psyche. BTS’ intentional departure from the masculinities of BIGBANG or the Backstreet Boys offers a new incarnation of the boy band, one that refuses the limitations of Western, propagandized stereotypes and White supremacist ideals, intent instead on promoting self-acceptance. My cynicism evaporated amid flowing garments, group hugs, playful touches, and smokey eyeshadows; replaced by a gentle affection for the seven boys from South Korea who have renewed my belief in the radical possibilities of self-love.

Sasha Cordingley is an arts and culture writer based in the UK.