Berenice Olmedo—Radical Alterity and the Crip/Disabled Subject

Berenice Olmedo, áskesis, installation view, 2019, [courtesy of the artist and Jan Kaps, Cologne, Lodos Gallery, Mexico City]

Share:

Berenice Olmedo is an artist whose work bridges a gestural politic and radical alterity, renewing and reconfiguring the conflict central to the notion of humanness through a distinctly Crip lens. Utilizing sculptural, performance, and social practice modes, Olmedo’s work circumvents the representational trap that is part and parcel of a reduced, oppositional framing of normative and non-normative, or able and disabled. Two of her major projects, The Bio-unlawfulness of Being: Stray dogs (2015) and Anthroprosthetic (2018–present), explicate the ways in which the human is, at its core, a sanitation project. The artist calls it “the political rationalization of the body … [or] the administration of life.” Olmedo uses feedback, contamination, and disruption to dislodge notions of disability, marginalization, and alterity from the regime of political management and calls into question how ableist and anthropocentric frameworks operate across the sociopolitical spectrum.

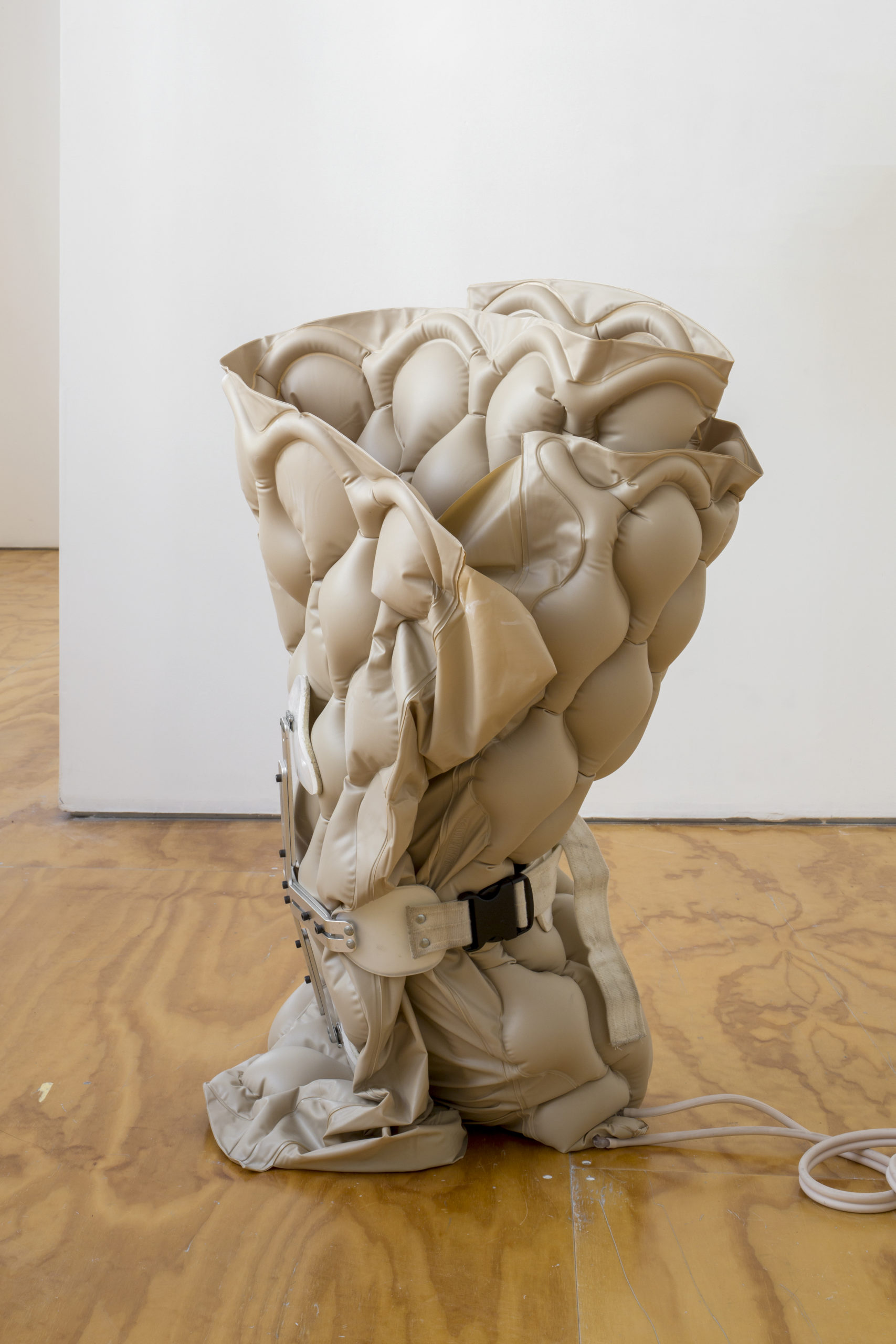

Berenice Olmedo, áskesis, 2019, alternating pressure pad, short Taylor back brace, Arduino boards, 83 x 40 x 40 centimeters [courtesy of the artist and Jan Kaps, Cologne, Lodos Gallery, Mexico City]

Olmedo’s work is particularly confrontational to and urgently needed by a US audience because her transnational Crip/Disabled perspective includes a critique of the violent hierarchical structures of global capitalism and the Western-centric framework that pathologizes the so-called Global South. As philosopher Paul B. Preciado outlines in Apartment on Uranus: Chronicles of the Crossing (2020), “In Western epistemology … the South is potentially sick, weak, stupid, incapable, lazy, poor …. The North always presents itself as healthier, stronger, more intelligent, cleaner, more productive, wealthier.” Recalling Pasolini’s use of extreme artworks in service of a radical alterity, Olmedo complicates and corrupts the construct of Western civility by critiquing essentialized or a priori notions of human nature. Instead, she situates humanness in a linguistic and historical sense—something that is taught/acquired after birth. Humanness is often understood in terms of a differentiation or manufactured separation from nature, enabled by an interlocking system of what Olmedo calls “techniques.” This separation—and the regulatory apparatus that manage, maintain, and extend it—serve as the major through line in Olmedo’s practice. As such, the work approaches alterity from a critical vantage point that allows us to rethink and resituate difference outside of the conceit of normativity—undermining the ways in which humanness has typically been produced through normative compulsion.

In her essay “Theory by Other Means: Pasolini’s Cinema of the Unthought” (2014) theorist Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli outlines the critical project of the filmmaker, writer, and intellectual Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–1975), a project he termed radical otherness or radical alterity. Pasolini developed radical alterity through his creative and critical practices, responding to the ways modernity sought to profoundly simplify and reduce the possibilities of subjectivity. Ravetto-Biagioli writes:

Like Michel Foucault, Pasolini was deeply critical of the way in which modern thought privileges the “human” as the subject of all knowledge but simultaneously evades thinking and thinking’s singular relation to life, the world, perception, experience, and ethics …. [Modern thought] creates a singular relation to an other who is both indispensable and exterior to the subject of knowledge.

In fierce opposition to the neocapitalist politic growing rapidly in Italy during the 1960s and early 1970s, Pasolini advocated for the production of extreme artworks that would resist consumption by the neoliberal framework. The infamous Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), the last film Pasolini completed before he was murdered that same year, epitomizes Pasolini’s use of extreme artworks in his praxis of radical alterity. Best synopsized by its affective power rather than a description of its plot, Salò reveals the contradictions within the Western narrative convention by pulling the viewer slowly and excruciatingly through a series of sections that, as Ravetto-Biagioli puts it, “reveal how the sacred myths of Western bourgeoisie are themselves based on the desecration of the sacred.” As such, Salò is widely considered to be one of the most shocking and depraved films ever made and is described as an affront to moral sensibilities, an unconscionable and instigative force that violates the boundary between representation and reality. Pasolini challenged the ways in which cinema is in service of thingness—wherein form, material, and idea are conflated. Shaped by his belief in radical alterity, Pasolini developed an active cinema that, per Ravetto-Biagioli, “corrupts the images of the past and the future by making incompatible associations.” Radical alterity and its construction of subjectivity as a changing set of relations, rather than a fixed point of view, allowed Pasolini’s work to contaminate and undermine the binary framework that renders otherness exclusively in terms of opposition. Ravetto-Biagioli argues that Pasolini’s work presents otherness as an “intense set of relations—an encounter between the senses, embodied perceptions, and material realities that produce a radical (desubjectified) affirmation of life.” Through his films and writing, Pasolini developed a praxis of radical alterity that utilized strategies of contamination, malfunction, and failure—making them generative. His work communicates through a vernacular of divergence, one that feeds back, contradicts, affronts, and puts into crisis. Otherness, for Pasolini, was as much a disruptive and instigative force as, in Ravetto-Biagoli’s words, “a radical affirmation of material life or sentient bodily experience.”

Berenice Olmedo, Jabón hecho a partir de grasa de perro (Soap made from the fat of run-over canines), 2015, canine fat, sodium hydroxide, dimensions variable [photo: courtesy of the artist and Jan Kaps, Cologne]

The ways in which radical alterity was developed by Pasolini through its application—what is referred to today by the academy as applied research—and connected specifically to embodied experience, foregrounds the need to theorize difference and otherness through an analysis of how the body is acted around, through, and upon by sociopolitical regimes. Although traces of Pasolini’s work exist within many contemporary identity-based projects, and he has continued to influence subsequent generations of cultural practitioners, the most vital and urgent aspects of his lineage can be found in the current discourse around a Crip/Disabled experience. During a 2009 lecture at the University of Hamburg, theorist Robert McRuer described the role of a gestural politic in his critical project Crip Theory. The project, outlined in his 2006 book of the same name, underscores how difference must be activated, or made generative, in order to dislodge it from systems of normativity. McRuer outlined how a gestural politic “constantly pushes outward, drawing attention to the hierarchies that structure the social on all levels,” which he differentiated from an emulative politic, which centers a series of core attributes, or identity qualifications, to make their emulation compulsory. In this way, Crip Theory has a kinship with radical alterity. As Pasolini’s project was invested in, per Ravetto-Biagioli, “the suspension of all identity formations” and utilized cinema because of its potential as “a medium that can call attention to itself, to its language and its devices, bringing the spectator into an ironic awareness that [their] own perspective is purely a fabrication,” Crip strategies seek to disrupt compulsory able-bodiedness by revealing the social, political, and economic structures that support and enable it.

Berenice Olmedo’s project The Bio-unlawfulness of Being: Stray dogs (2015) emanated from her “research on [the] social and legal problems that canine species represent in Mexico.” Olmedo observed how, in Mexico, a dog is an extremely paradoxical being … on the one side there are official norms that consider it as “dangerous fauna,” and on the other the Federal Civil Code refers to it as a commercial ‘good’—as an object or a thing. Olmedo’s project examines the canine as a political entity and its role within an “ideological, legislative, and coercive apparatus in which both physical and ethical forces are used to condition [its] behavior ….” Specifically, Olmedo’s project harvested, processed, repurposed, and commodified the corpses of runover stray dogs, drawing attention to delineations between leisure and vagrancy, as well as vital and pathological states. It also questions the utility of such distinctions in the construction and regulation of humanness. In the first phase of the project, titled HOMO FABER or anthropotechniques: work, Olmedo collected canine corpses from roadsides, documenting their features and locations and delivering them to the state-contracted center for the collection and disposal of stray dogs—a so-called Canine Wellness Center.

When Olmedo requested to keep the collected corpses, a representative informed her of a legal restriction that prevented the center from donating, selling, or giving the corpses to any public or private institution with for-profit, research, or educational purposes. The stray dogs were denied the distinction even of property—bureaucratically dispossessed and exterminated. In another phase of the project, Canine TANATOcommerce or the political-ethical dilemma of merchandise, Olmedo continued to harvest the corpses independently. Instead of donating them to the center, she processed the bodies at a tanning workshop and chemistry laboratory, producing clothing and textiles from the hides, and bars of soap from the body fat. The products were then offered for sale at a street market in the city of Puebla where, the artist says, “[living dogs] are sold under unsanitary and exploitative conditions.” Olmedo draws attention to the ways in which the state administers the life of the canine by positioning property and pathogen as oppositional terms. The vagrant canine is pathologized by the state on the basis that it could potentially pose a risk to the human population by contracting and spreading rabies.

Berenice Olmedo, Jabón hecho a partir de grasa de perro (Soap made from the fat of run-over canines), 2015, canine fat, sodium hydroxide, dimensions variable [photo: courtesy of the artist and Jan Kaps, Cologne]

The Bio-unlawfulness of Being: Stray dogs moves beyond the dog as a subject and renders the system that produces its subjectivity, as well as the intersecting medical, social, and political economies that administer its life. Through this gesture, Olmedo points us toward the “canine species [as] an anthropological machine that can generate a recognition of what is human.” Or, to phrase it another way, how the life of any dog is administered by social, legal, political, and economic apparatus reflects and reveals what constitutes the human. The same system that destroys the stray dog produces humanness.

Olmedo’s Anthroprosthetic sculptures deepen and complicate our understanding of prostheses and their connection to Crip/Disabled experience in valuable ways. The works undermine and corrupt the self-evidentiary construct of an able/disabled binary. Olmedo creates physical iterations at the intersection between medical and social models of disability, thereby revealing the degree to which those models are conflated in our collective understanding. Much of the art that takes disability as its subject matter struggles to disentangle (a) disability as social, political, and economic construct from (b) those individual bodies that these systems modify. Olmedo, through a radically alterior framework, rejects essentializing disability and moves toward an analysis of the system of compulsory able-bodiedness and its architecture. This is achieved, in part, by delinking prosthetic artifacts and corrective apparatus from the bodies they are used to modify.

Berenice Olmedo, Olga, 2018, HKAFO (Hip, Knee, Ankle, Foot Orthosis), polypropylene, aluminum, velcro, mechatronics, motors, sensors, microcontrollers, 110 x 30 x 15 centimeters [courtesy of the artist and Jan Kaps, Cologne]

Olga (2018), from the Anthroprosthetic series, and áskesis (2019), from a related body of work, typify the way Olmedo’s sculptural systems allow prosthetic artifacts to reveal their corrective impetus. Olga, which consists of hip, knee, ankle, and foot orthoses, polypropylene, aluminum, and Velcro is activated by a mechatronic system of motors, sensors, and microcontrollers that animate the piece in a perpetual attempt to achieve a vertical standing posture. áskesis (2019) is a trio of pressure pads corseted by short Taylor back braces whose slow inflation and deflation is regulated by Arduino boards. As the pressure pads attempt to inflate and unfold the braces restrict their progress until they eventually deflate. Without the presence of a human body, these works perform overlapping and contradictory series of functions to strange and unsettling ends. The effect is of a slow and grinding attempt to regulate a nonexistent figure. The systems push, constrict, limit, and struggle against each other, rendering these so-called assistive technologies in a strained and even violent manner. This inversion comes in stark contrast to the benevolent and altruistic framing to which we are accustomed in a culture that positions disability as a weakness, malfunction, or failure of the human body to realize its normal state. Similarly to the exploration, in The Bio-unlawfulness of Being: Stray dogs, of the means by which canine life is profoundly regulated or administrated, a Crip/Disabled experience is, in part, a corporeality that exists in close proximity to destructive, violent, carceral, and marginalizing modes. The Anthroprosthetic series resituates and reimagines the disabled subject outside the essentializing and restrictive framework of the medical model of disability.

Olmedo’s work moves us toward understanding the human condition of disability and reflecting more accurately upon humanness as a production. Olmedo argues that the human body is inherently disabled, unable to exist without the support of prosthesis. Prosthetics exist in the expanded field of techniques and technical artifacts that assist the human in producing itself. Olmedo’s work utilizes the affective potential of art to think and unthink our relationship to otherness. Like the projects of radical alterity and Crip Theory, Olmedo’s work extends and expands notions of difference—making them generative. Through a practice that bridges theoretical and applied modes of inquiry, Olmedo’s work provides us with new and radical ways of imagining malfunction, failure, corruption, and contradiction.

Christopher Robert Jones is an artist and writer based in Illinois. Their research revolves around the “failure” or “malfunctioning” of the body and how those experiences are situated at points of intersection between Queer and Crip discourses. They are currently a specialized faculty in New Media at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.