Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive

Baseera Khan, I Am and Archive, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, New York]

Share:

Undefined, the first-person speaker of the title for Baseera Khan’s first solo museum show, could be the artist, the individual artworks, the exhibition, or, most likely, all three. Curated by Carmen Hermo, I Am an Archive is energetic and ambitious. Eleven new works appear alongside a number of earlier ones, which date back to 2017. They include music, sculpture, video, photography, collage, textiles, and drawings. Khan—winner of the museum’s second annual UOVO prize, which is awarded to an emergent Brooklyn-based artist—moves through an array of media and materials, trying to capture the textured co-existence of multiple languages and influences. They posit themself as an archive, physically and psychologically, their body carrying a history of imperialism, migration, exploitation, and discrimination. Khan was born in Denton, TX, to Muslim Indian immigrants from Bangalore. Their family heritage is a collage of influences from Iran, Afghanistan, and East Africa, shaped by movement and exchange.

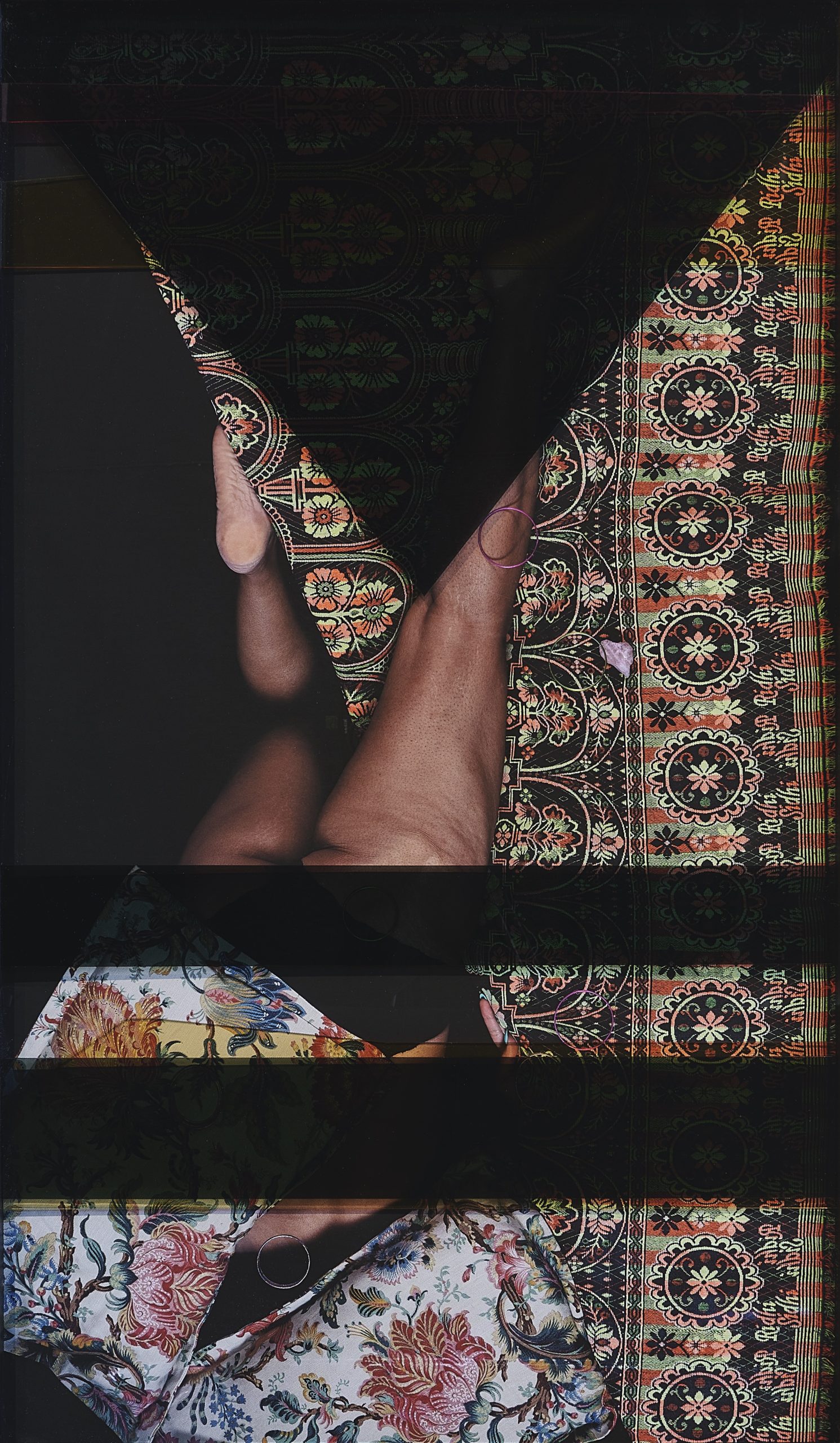

Baseera Khan, I Arrive in a Place with a High Level of Psychic Distress, (Black), 2021, Chromogenic photograph and laser-cut acrylic, 62 × 37 inches [photo: Stephen Takacs; courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery, New York, Brooklyn Museum, New York]

Textiles constitute a central component—conceptually and materially—in the artist’s archival project. As the child of a seamstress and dressmaker, Khan draws on a repository literally crafted by their mother’s hand, kept alive and reproduced through annual rituals of making new clothes for Eid celebrations. In Chandeliers (2021), four acrylic sculptures dance like disco balls to a soundtrack that was written and recorded by Khan while preparing for the exhibition. Intricate and mesmerizing, the lantern-like forms playfully reflect light throughout the space. Like embroidered bling, their patterns take inspiration from the South Asian designs of Khan’s childhood. The soundtrack emanates from a hybrid sculpture, I Am an Archive, Speaker (2021)—part Hindu goddess, part stylized selfie. In four collages titled I Arrive in a Place With a Higher Level of Psychic Distress (2021), the artist layers photographs of their own body with colored acrylic panels. The fabrics’ vibrant patterns and the adornment of Khan’s body with jewelry and nail polish serve more than a decorative function. Instead they surround and shield a body from the constant state of scrutiny and surveillance. These fabrics are registers of complex, layered, polyvalent histories and geographies, as well as protection from intrusive eyes.

Khan repurposes textiles again in their minimalist sculpture Snakeskin Column (2019). The foam insulation form—14 feet tall and 6 feet wide—is wrapped in handmade Kashmiri rugs and sliced into seven pieces (on exhibit here are Number 2, Number 6, and Number 7 in the series). The simplicity of the structure contrasts with the intricacy of the rug designs—a pink and seemingly soft, yet manufactured, core encrusted with a lavishly decorated exterior—and gestures to the ever-present tensions involved in cross-cultural interactions, especially ones marred by uneven power dynamics. As the monument is deconstructed, dismantled, it sheds its skin, exposing an unexpected interior. Throughout the exhibition, Khan directs us to the materiality of their practice. Human and synthetic hair braided to form a 13-foot rope that the artist uses to scale a rock-climbing wall, petroleum-based acrylic, silk rugs, or ornate jewelry: each is a deliberate reflection on capitalist economies of extraction and imperialist trade routes that continually ravage the Middle East and South Asia.

Collage emerges as a mode of storytelling for Khan, one that resists the linear narratives of museum displays and that counters the flattening of geography. As an alternative mode of record-keeping and narration, it privileges nonlinear connections. In the series Law of Antiquities (2021), they examine the museum as a space that produces knowledge, meaning, and power; through the processes of acquiring and ordering, categories are created, geographies demarcated, and disciplines defined.

Baseera Khan, Snake Skin (Column6), installation detail, 2019, Pink Panther FOAMULAR, plywood, resin dye, custom handmade silk rugs made in Kashmir, India, 72 × 22 × 72 inches [photo: Dario Lasagni; courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery, New York]

The Brooklyn Museum’s Islamic art collection—which includes approximately 2,000 objects spanning 13 centuries and contains the most significant collection of Qajar art outside Iran—is emblematic of museology’s centrality to the expansion of imperial and colonial ambitions. The series title alludes to regulations that protect cultural objects and the rules that govern Khan’s own engagement with them. Throughout the photocollages, the artist never touches the objects directly. Instead it is the conservator’s bespoke-gloved hands that handle them. Khan’s spatial relationship to these objects is never more than partially disclosed; like many works in the exhibition, the photographs play with the relationship between what is revealed and what remains concealed.

Although I Am an Archive is vast in its concerns, it is impossible to escape the persistent feeling that, in relying too heavily on the misconceptions and stereotypes it is attempting to subvert, the exhibition reproduces them. Replete with images of Muslim women, shrouded in mystery and hidden from view, alongside an array of orientalist paraphernalia, I Am an Archive constantly teeters on the brink of exoticization. One is reminded of Shirin Neshat’s much-celebrated, but arguably problematic, 1990s photographs, in which armed, veiled women—with heavily kohled eyes, and skin covered in handwritten Farsi poetry—stared back at viewers in defiance. Moreover, the exhibition participates in a re-education of its audience on the fundamentals of Islam. Wall texts explain the religion’s pillars and practices, encouraging an anthropological approach to the work. Ultimately, I Am an Archive raises urgent questions about the kind of “educational” labor art institutions expect artists of color to perform in return for their inclusion.

Baseera Khan, Mosque Lamp and Prayer Carpet Green from Law of Antiquities, 2021, Archival inkjet print, artist’s custom frame, 33 × 24 inches [courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery, New York, Brooklyn Museum, New York]

Although the Brooklyn Museum has often been praised for its efforts to diversify activities and engage with local communities, in recent years there has been increased criticism regarding the disconnect between the museum’s public image and its treatment of BIPOC employees. With this recent history in mind, and considering some disconnect between I Am an Archive’s apparent aims and its presentation, one must ask: What kinds of exhibition activism, so often articulated through identity politics, does the Brooklyn Museum—an institution naively celebrated as “the museum that’s doing it right”—accommodate or encourage?

Dina A. Ramadan teaches modern and contemporary Middle Eastern cultural production at Bard College. She is currently completing a manuscript titled The Education of Taste: Art, Aesthetics, and Subject Formation in Colonial Egypt. Her writing on art has appeared in art-agenda, ArtReview, Africa Is a Country, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, and elsewhere.