Azza El Siddique: In the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed

Azza El Siddique, List Projects 25: Azza El Siddique, installation view, 2022 [photo: Mel Taing; courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather, MIT List Visual Arts Center, New York]

Share:

Azza El Siddique’s exhibition at MIT List Visual Arts Center is a treatise on scent and transformation. In the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed proposes scent as a cultural signifier, an object of commerce, an invocation of memory, a lived experience, a historical artifact, a religious offering, a political intermediary, and—in this case—an artist’s tool. Located in the Bakalar Gallery, the installation consists of recurring elements: welded metal, video monitors, recessed heat lamps, and bukhoor—the subject and material that all other elements support. Historically, bukhoor is an aromatic used in Islamic mortuary rituals that originated in ancient Nubia. Materially, bukhoor is a waxy substance made of compressed sandalwood chips, fragrant resins including frankincense, amber, oudh, and European scents made for export to North African markets that coalesce in sugar. Today, bukhoor is a familiar aroma in Sudanese and diasporic Sudanese households. El Siddique is Sudanese, and she grew up in Canada.

Azza El Siddique, List Projects 25: Azza El Siddique, installation view, 2022 [photo: Mel Taing; courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather, MIT List Visual Arts Center, New York]

Warmth, as a temperature and a smell, permeates the gallery, is contrasted by the low light and visual coolness of the concrete floors, and is punctuated by the acerbic red glow of heat lamps. Large metal structures echo the perimeter of the room and divide the small space. Geometric lines of welded metal connect items contained in the installation and provide sightlines of frames within frames within frames. Reconstructed floorplans are those of ancient Nubian sacred sites, specifically the birth house of Dedwen, a shape- and gender-shifting Nubian god associated with natural resources, notably incense.

Azza El Siddique, In the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed, installation detail, 2022, welded steel drawing, two vertical steel bars [photo: Mel Taing; courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather, MIT List Visual Arts Center, New York]

Azza El Siddique, In the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed, installation detail, 2022, welded steel drawing, two vertical black steel bars [photo: Mel Taing; courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather, MIT List Visual Arts Center, New York]

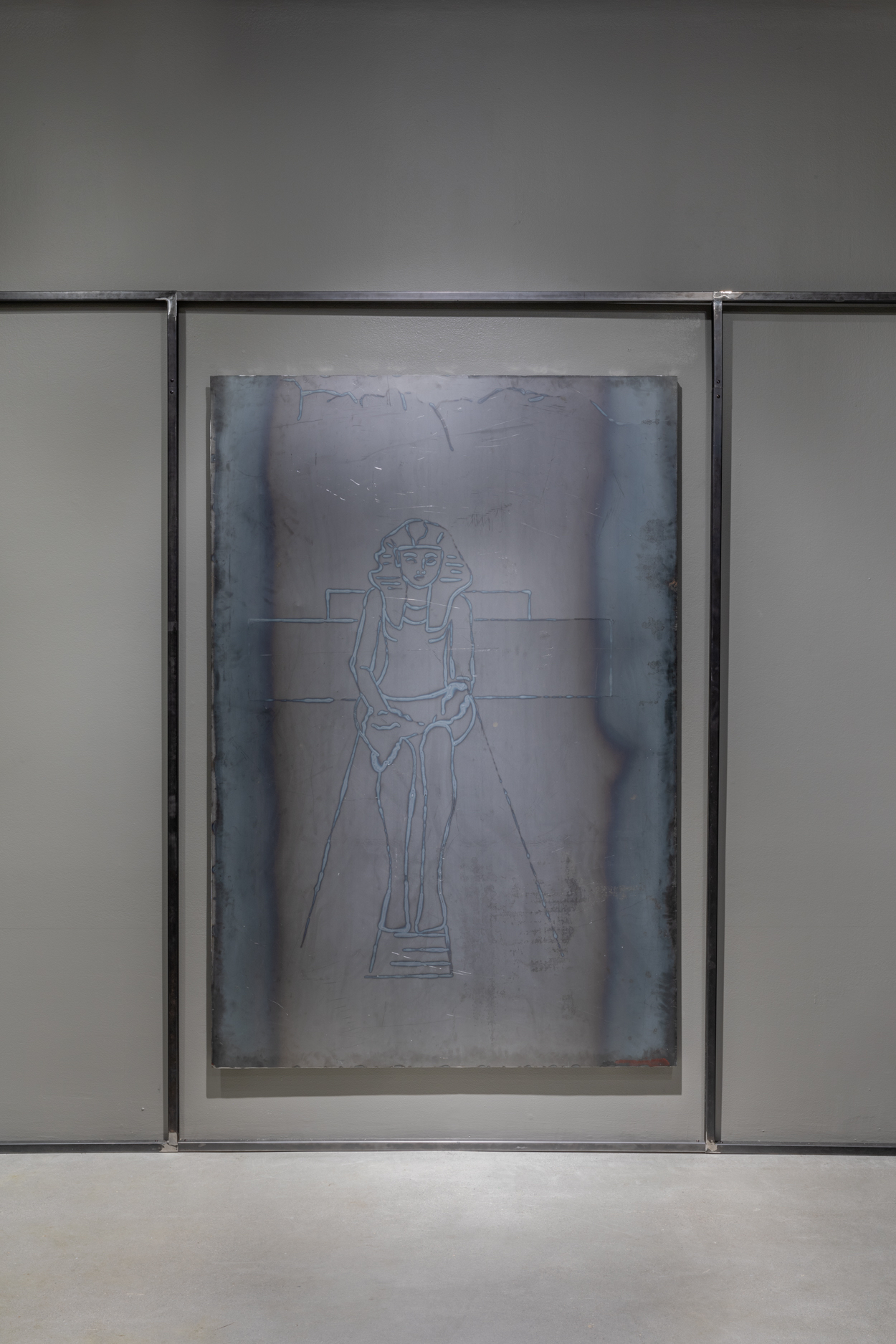

Housed within the suggested walls are three drawings. Using MIG and TIG welding, the artist sketched flowers, leaves, and ancient Egyptian iconography onto stainless steel panels. Two drawings feature Hatshepsut, the “female king,” who presented herself with masculine features and royal gravitas to solidify her power as pharaoh. Hatshepsut’s trade enterprises brought frankincense and myrrh to ancient Egypt. There is pleasure and play in these images: an open hand, a blossoming flower, an Egyptian god—all blasted onto the surface of steel, a chosen material of Western modernism and industrial expansion.

Azza El Siddique, List Projects 25: Azza El Siddique, installation view, 2022 [photo: Mel Taing; courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather, MIT List Visual Arts Center, New York]

In the middle of the room are opposing video monitors, mounted onto the architectural armature. On the monitor facing the entrance, a 3–D rendering of red, white, and blue molecular structures turns slowly against a black background. Scent is represented again in this depiction of bukhoor’s ingredients’ molecular structures. Within the model, scent is disclosed, and obscured, by visual form. The scientific illustration of chemical compounds reveals what scent looks like while also acknowledging that it is invisible to the human eye. The opposite monitor shows an image that is harder to identify. The camera sweeps over a craggy virtual landscape of pungent orange, yellow, and pink. Topographical, but also bodily in appearance, the view pulls back to reveal a perfume bottle floating in space. Both videos represent fragrance with such proximity that identifiable objects become difficult to discern.

Behind the column of monitors is the bukhoor itself, displayed on a polished metal box—or altar—beneath one of the Hatshepsut drawings. An outstretched hand is burned into the side of the box. This metal altar has the largest footprint in the gallery. Beneath the altar beams a stringent red glow from heat lamps that cuts across the edge of the room. Promising danger and inspiring hesitancy, the box is noticeably hot. Atop the altar is bukhoor, cast into the form of five waterlilies, which are also symbols of the Nubian deity Dedwen. Although smell usurps material aesthetics in this work, even the appearance of the bukhoor is potent. Dense and sticky, umber in color, it exists in stark contrast to the muted metal that constitutes the rest of the installation. Whereas some waterlilies here are still fully formed, others have melted and lost definition because of the heat lamps beneath them. The bukhoor flowers degrade over time and serve as the ticking clock of the work.

The action of burning—the artist’s means of creation and the physiological transformation of energy—emerges again and again. Burning is taken up by almost every aspect of the exhibition: the scored drawings; the welded architectural form; the melted bukhoor; and the heat lamps, both felt and seen. This act of creation mirrors El Siddique’s past work, which invited entropy by using such natural forces as water, light, and heat. Furthermore, the title itself directly addresses change. For El Siddique, annihilation does not imply total destruction. Instead, she applies the term annihilation as physicists define it. Annihilation is a principle in physics whereby the force of subatomic collisions converts matter into energy. Subsequently, the installation demands not a cessation but a transformation. For El Siddique, production and destruction are one and the same.

Azza El Siddique, In the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed, installation detail, 2022, black steel architecture frames, metal table, red heat lamps, bukhoor sculptures, welded steel drawing [photo: Mel Taing; courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather, MIT List Visual Arts Center, New York]

In the place of annihilation proposes a narrow scope: a limited subset of materials—metal, and bukhoor; a specific means of production—heat; and a focused subject—scent. Yet, within these articulated elements, the artist iterates, widening the application and conceptual reach of the work. By weaving in such references as the ancient Egyptian trade, Nubian mythology and architecture, and personal memory, El Siddique meditates upon the universal and approaches the ineffable: time’s power to transform.

Courtney McClellan is an artist and writer originally from Greensboro, NC. Her work addresses speech, performance, and civic engagement. She has served as the Fountainhead Fellow in the Sculpture and Extended Media Department at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA; the Roman J. Witt Artist in Residence at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, MI; and an Innovator in Residence at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.