Athena Tacha

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS November/December 1989, Vol. 13, issue 6.

Athena Tacha was born in the provincial town of Larissa, Greece. She studied as a sculptor in Greece before moving to Paris, where she received the doctorate in aesthetics from the Sorbonne. Now teaching sculpture at Oberlin after serving as director of the Oberlin Art Museum, she has established a reputation for her public site works and memorials. Photographs and maquettes of Athena Tacha’s site sculptures and of her related artists’ books and other projects were presented at the High Museum of Art in 1989, in an exhibition curated by John and Catherine Howett. The interview which follows was arranged by the High Museum.

Mildred Thompson: I understand you teach a course at Oberlin called “Sculpture and Environment.”

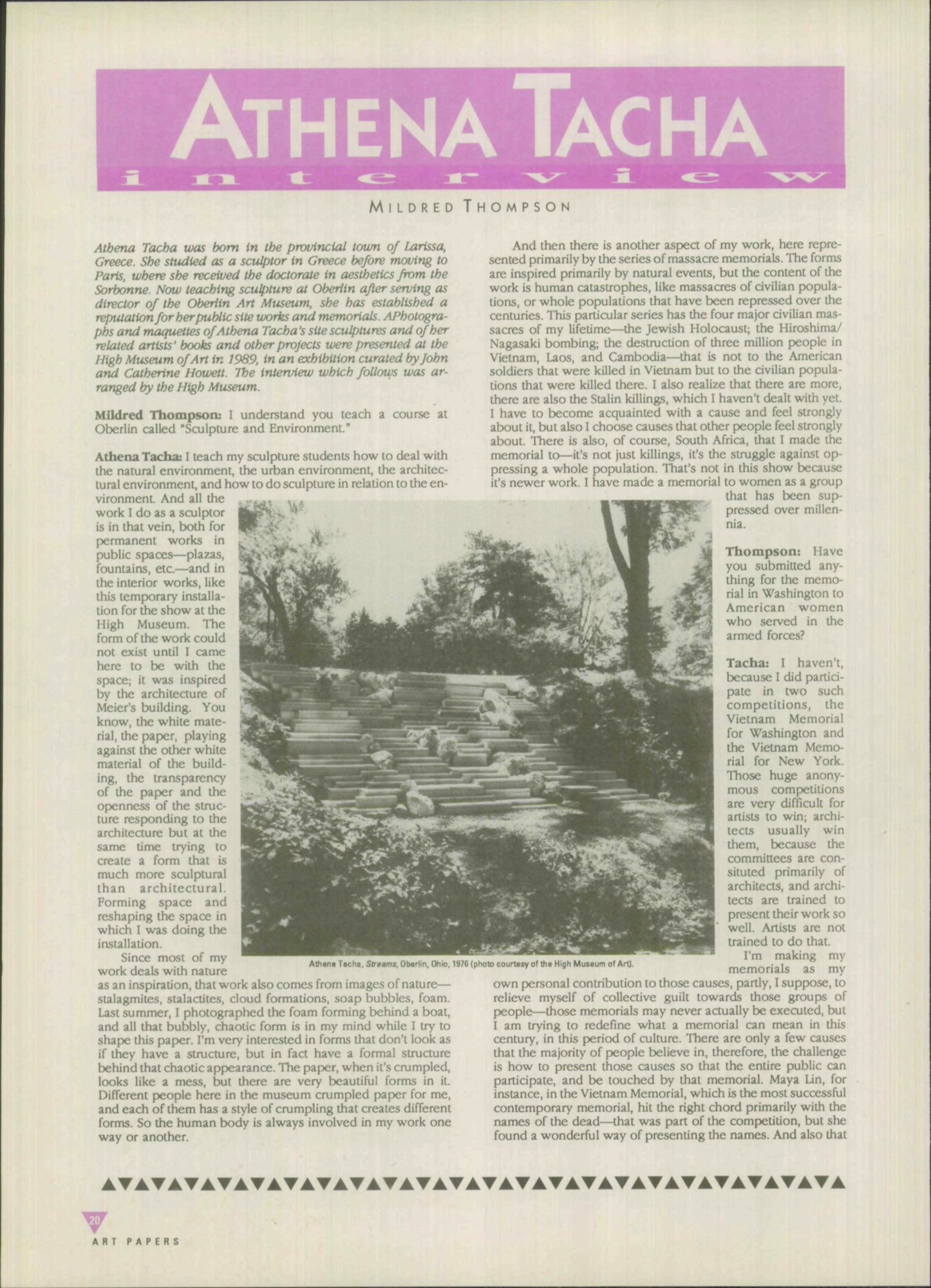

Athena Tacha: I teach my sculpture students how to deal with the natural environment, the urban environment, the architectural environment, and how to do sculpture in relation to the environment. And all the work I do as a sculptor is in that vein, both for permanent works in public spaces—plazas, fountains, etc.—and in the interior works, like this temporary installation for the show at the High Museum. The form of the work could not exist until I came here to be with the space; it was inspired by the architecture of Meier’s building. You know, the white material, the paper, playing against the other white material of the building, the transparency of the paper and the openness of the structure responding to the architecture but at the same time trying to create a form that is much more sculptural than architectural. Forming space and reshaping the space in which I was doing the installation.

Since most of my work deals with nature as an inspiration, that work also comes from images of nature— stalagmites, stalactites, cloud formations, soap bubbles, foam. Last summer, I photographed the foam forming behind a boat, and all that bubbly, chaotic form is in my mind while I try to shape this paper. I’m very interested in forms that don’t look as if they have a structure, but in fact have a formal structure behind that chaotic appearance. The paper, when it’s crumpled, looks like a mess, but there are very beautiful forms in it. Different people here in the museum crumpled paper for me, and each of them has a style of crumpling that creates different forms. So the human body is always involved in my work one way or another.

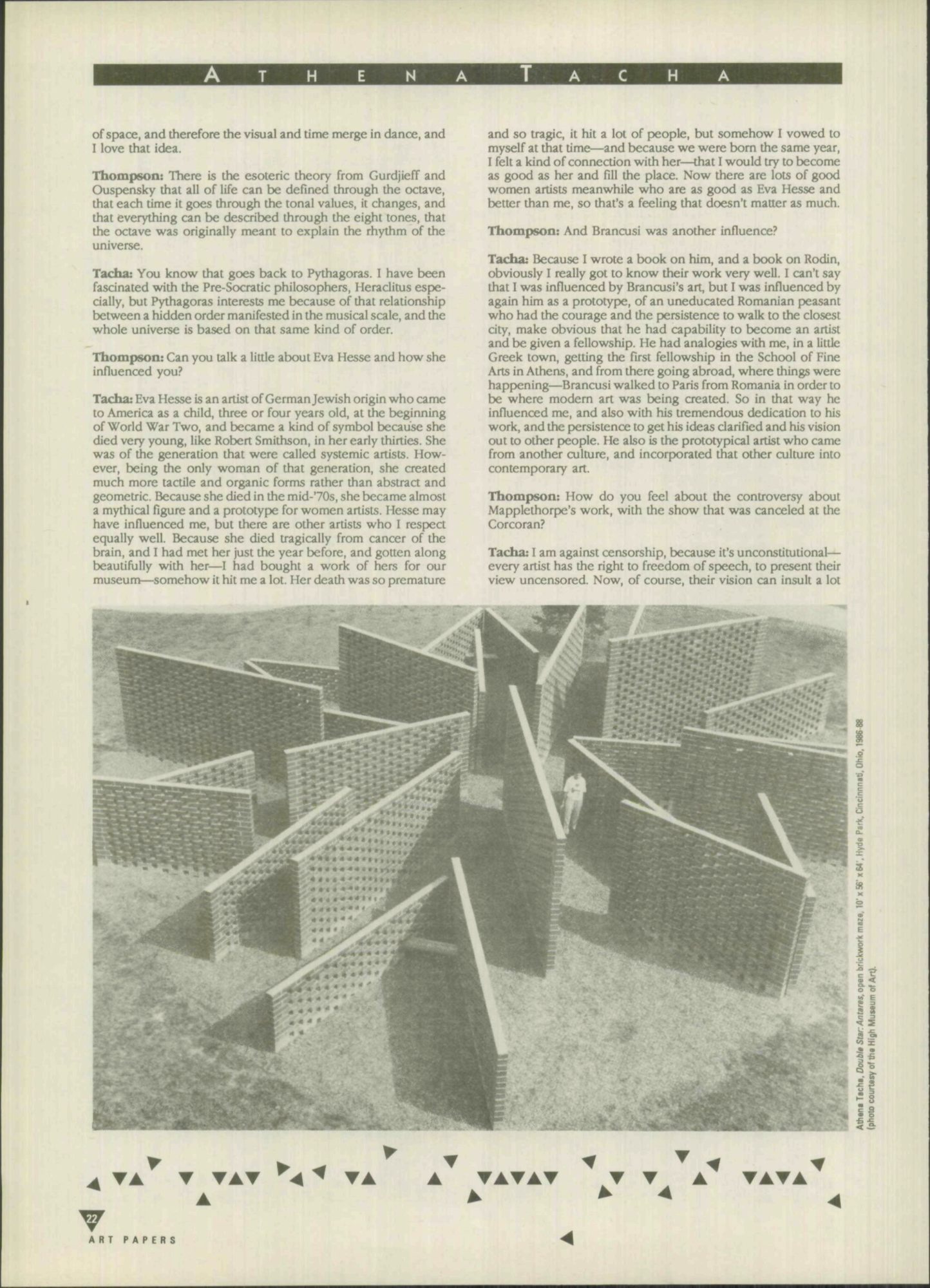

And then there is another aspect of my work, here represented primarily by the series of massacre memorials. The forms are inspired primarily by natural events, but the content of the work is human catastrophes, like massacres of civilian populations, or whole populations that have been repressed over the centuries. This particular series has the four major civilian massacres of my lifetime—the Jewish Holocaust; the Hiroshima/ Nagasaki bombing; the destruction of three million people in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia—that is not to the American soldiers that were killed in Vietnam but to the civilian populations that were killed there. I also realize that there are more, there are also the Stalin killings, which I haven’t dealt with yet. I have to become acquainted with a cause and feel strongly about it, but also I choose causes that other people feel strongly about. There is also, of course, South Africa, that I made the memorial to—it’s not just killings, it’s the struggle against oppressing a whole population. That’s not in this show because it’s newer work. I have made a memorial to women as a group that has been suppressed over millennia.

Thompson: Have you submitted anything for the memorial in Washington to American women who served in the armed forces?

Tacha: I haven’t, because I did participate in two such competitions, the Vietnam Memorial for Washington and the Vietnam Memorial for New York. Those huge anonymous competitions are very difficult for artists to win; architects usually win them, because the committees are constituted primarily of architects, and architects are trained to present their work so well. Artists are not trained to do that.

I’m making my memorials as my own personal contribution to those causes, partly, I suppose, to relieve myself of collective guilt towards those groups of people—those memorials may never actually be executed, but I am trying to redefine what a memorial can mean in this century, in this period of culture. There are only a few causes that the majority of people believe in, therefore, the challenge is how to present those causes so that the entire public can participate, and be touched by that memorial. Maya Lin, for instance, in the Vietnam Memorial, which is the most successful contemporary memorial, hit the right chord primarily with the names of the dead—that was part of the competition, but she found a wonderful way of presenting the names. And also that simplicity, and the underground, and the blackness, and the reflection of the people in the granite, all of those contribute greatly to the memorial being very touching and the siting of it pointing towards the obelisk and towards the Lincoln Memorial. While Lin is predominantly an architect, she’s also a sculptor. But her solution is an architectural solution to a memorial, and I want to find more sculptural solutions, not necessarily by putting statues on the memorial, because that’s too traditional a type of solution, but having the memorial more plastic in form, and having images of people. I don’t think that you can speak to people about a particular cause without having images of people, so I am putting a lot of documentary photographs in my memorials.

Thompson: Do you not think that the line is very thin between the architect who is doing these sculptural presentations…

Tacha: And the sculptor? Yes, it is. But because we come from different trainings, I think that always an architect thinks more abstractly, and a sculptor thinks more concretely, in a more plastic way. I am trained to shape things with my hands, whereas the architects draw on paper, and therefore their approach is much more intellectual and abstract, and mine is much more physical. The form is more physical, if it’s shaped with your hands, or if it has plasticity, tactility, an appeal to your physical entity and your senses, which usually architects’ conceptions don’t. Also, introducing photographs is for me a way of making a more specific cause, and appealing to parts of the soul or of the mind that abstract form alone would not.

Thompson: So this brings in an emotional angle. Do you think that the work would project that same kind of emotion if the photographs were not there?

Tacha: No. That’s why I end up with the photographs. The reason I started thinking about a memorial is that I’m a very socially aware person; everybody who suffers touches me deeply. My work had been dealing with the beauty of nature, and not with human suffering. So I had been trying to combine my social and human concerns with my sculpture, which is more my wonder in front of nature. By bringing photographs or inscriptions into my sculpture, I found a way of, not necessarily giving the history of the events, but giving facts about the events that are extraordinary and strong and touching. So somehow I see my memorials like theater; you walk through them and the images bombard you, and the images are very violent because the events were very violent. The inscriptions give you the facts of the violence, and at the same time, the forms pacify you. It’s like ancient tragedy; the subjects were extremely violent, people were killing each other, or being puppets of the gods and suffering, and yet the beauty of the poetry purged the soul, so when you came out of ancient Greek tragedy you felt uplifted. And that’s my aim with my memorials, to have the form very beautiful and very peaceful, so that the violence of the images and the information plays against it, so that it becomes a memorable event, but it makes you a better human being, rather than wanting more violence. I don’t want violence to create violence, I want violence to be suppressed.

On the other hand, there are many other social causes that interest me very much, such as the destruction of our environment through pollution. “Landmarks” is a memorial to human civilization in terms of the great peaks of technology and the great destruction which technology has created. I also just did a sculpture which is a homeless shelter, because I think that the problem of the homeless just has to be faced, we cannot let it continue this way. So I have made a sculpture that’s like a small house, with showers and toilets in the middle, and then little rooms for individuals all around, like a beehive, where every person can have a little room of their own, a little protection from the elements, a little privacy, and a permanent address. It’s very cheap to build, temporary, but it can be a step toward better solutions, and relieve some of the situation at this point in big cities, because with very little money, you can house in a space like that one hundred fifty people, in four stories, with individual rooms for every person. So I am putting more and more of my social concerns into my sculpture.

Thompson: But already that’s architectural.

Tacha: Yes, that is the most architectural thing I’ve done, the only sculpture that has interior spaces. But again, if you look at the form of it, you will see that it is a sculptor’s solution, because it’s very beautiful, because I believe that it is important for people, even if they are hungry and poor, to be surrounded by something that humanizes them, that doesn’t make them feel like dirt or like machines. Institutionalization is not good at any level. I want an environment that enhances your experience in life and makes you realize that what’s around you can be beautiful, rather than wiping out your humanity. So it is an artist’s solution to an architectural problem. It is not permanent architecture, it’s temporary.

Thompson: You keep separating the artistic and the architectural thing.

Tacha: Well, architects are artists too, but they are trained differently. Architects before the 19th century were also sculptors. For instance, both Michelangelo and Bernini were sculptors as well as architects. However, in the late 19th century, technology and the development of steel and concrete created so much more specialization, and the need for bigger housing geared people to engineering problems, so the architects separated themselves from the fine arts.

Thompson: But don’t you feel that at this point all these things are merging?

Tacha: It’s a period of synthesis; the architects are feeling the need to become artists, and the artists are feeling the need to go towards architecture. So that’s why there’s a whole group of artists who are doing architectural work or landscape work. It’s definitely a period of synthesis; there has been too much overspecialization. Although each person’s training is part of their vision—you know, how you’ve been trained, that’s how you see things—there are still different approaches to the various problems. I think that’s good too, it’s good to have different points of view, just so that you don’t regiment it into separate things.

Thompson: You’ve used the dance as inspiration. You brought that up a little when you said that you wanted the public to have a physical experience of your work. Are you a dancer?

Tacha: No, I’m not a dancer, I love dancing though, and somehow I experience things in space with my body, I’m very sensitive to rhythm. Every time I hear music, my body just moves. And so when I make steps, for instance, I always try to express through them various rhythmic phenomena in nature, and also I’m thinking of how the body will respond to those rhythmic phenomena. For example, going up steps, if they’re enormous steps, is a dull experience, just a tiring, dull experience, but if you make the steps interesting, like interspersing flat areas, or turning the direction here and there, or creating every now and then shorter steps or taller steps, that makes you immediately aware of your body, and once you become interested and involved, the tiredness disappears. I want people to respond to their relation to the ground, and become conscious of it. Through that play between ground and body, I become aware of other rhythmic phenomena and formal beauties that I see in our environment So it is almost dance if the steps make you perform various rhythmic movements. Also, you experience the sculpture through time. Dance is really movement of the body in space, therefore it’s a time phenomenon. The other thing is, I read that in ancient India, dance was considered the mother of the arts, because it’s related to music through the rhythm of it, it’s related to sculpture through the use of space, and therefore the visual and time merge in dance, and I love that idea.

Thompson: There is the esoteric theory from Gurdjieff and Ouspensky that all of life can be defined through the octave, that each time it goes through the tonal values, it changes, and that everything can be described through the eight tones, that the octave was originally meant to explain the rhythm of the universe.

Tacha: You know that goes back to Pythagoras. I have been fascinated with the Pre-Socratic philosophers, Heraclitus especially, but Pythagoras interests me because of that relationship between a hidden order manifested in the musical scale, and the whole universe is based on that same kind of order.

Thompson: Can you talk a little about Eva Hesse and how she influenced you?

Tacha: Eva Hesse is an artist of German Jewish origin who came to America as a child, three or four years old, at the beginning of World War Two, and became a kind of symbol because she died very young, like Robert Smithson, in her early thirties. She was of the generation that were called systemic artists. However, being the only woman of that generation, she created much more tactile and organic forms rather than abstract and geometric. Because she died in the mid-’70s, she became almost a mythical figure and a prototype for women artists. Hesse may have influenced me, but there are other artists who I respect equally well. Because she died tragically from cancer of the brain, and I had met her just the year before, and gotten along beautifully with her—I had bought a work of hers for our museum—somehow it hit me a lot. Her death was so premature and so tragic, it hit a lot of people, but somehow I vowed to myself at that time—and because we were born the same year, I felt a kind of connection with her—that I would try to become as good as her and fill the place. Now there are lots of good women artists meanwhile who are as good as Eva Hesse and better than me, so that’s a feeling that doesn’t matter as much.

Thompson: And Brancusi was another influence?

Tacha: Because I wrote a book on him, and a book on Rodin, obviously I really got to know their work very well. I can’t say that I was influenced by Brancusi’s art, but I was influenced by again him as a prototype, of an uneducated Romanian peasant who had the courage and the persistence to walk to the closest city, make obvious that he had capability to become an artist and be given a fellowship. He had analogies with me, in a little Greek town, getting the first fellowship in the School of Fine Arts in Athens, and from there going abroad, where things were happening—Brancusi walked to Paris from Romania in order to be where modern art was being created. So in that way he influenced me, and also with his tremendous dedication to his work, and the persistence to get his ideas clarified and his vision out to other people. He also is the prototypical artist who came from another culture, and incorporated that other culture into contemporary art.

Thompson: How do you feel about the controversy about Mapplethorpe’s work, with the show that was canceled at the Corcoran?

Tacha: I am against censorship, because it’s unconstitutional— every artist has the right to freedom of speech, to present their view uncensored. Now, of course, their vision can insult a lot of other people, and that’s why when it becomes public, when you put it out in public, there are responsibilities. And that’s why, if it was a permanent public display, I would not be in favor of it. But since it is a temporary exhibition, it is like film— I mean, you can say at the entrance, “This is not a display for children. Parents, be aware that there is X-rated material in the exhibition.” But you cannot block it out of the public view for fear that the politicians will not support it. Now, I personally did not see that Mapplethorpe retrospective, I saw the retrospective at the Whitney, which had less—I think—homoerotic and sadomasochist material. I cannot say that I am not affected when I see it—I mean, it is offensive to most sensitivities. Probably however other people feel liberated to see it expressed through an artist’s daringness. I don’t happen to like especially Mapplethorpe’s art—not because of that idea but because he is too beautiful, too studied, too perfect and traditional, almost. They can be beautiful photographs, just gorgeous photographs, but I’m not sure that they have that much fresh to say. I also think that public artists, artists who undertake to speak to a large audience and to put their work out in the public domain, have much more responsibility to general sensitivity. In other words, I would not want to see as a permanent work of art, like a mural, of Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic, really intense images. Even Richard Serra—I respect Serra enormously as an artist, I think he is a great artist, but I think as a person he is totally insensitive to the public, and I don’t think his work is digestible by the general public; therefore it should not be placed in the public domain, at least not without the consent or education of the public. Obviously you cannot have everybody agree on everything. There will always be disagreement, there will always be somebody offended by anything. But at least you should not push down the throat of the community something that they revolt against. In other words, I think public art should not deliberately be offensive. It should make an effort, without diluting the content, the value of the art, to be inoffensive, to be approachable. In other words, I don’t believe that masterpieces have to be ugly, I don’t believe that good art has to stir by offending people, by creating a scandal. I don’t believe in that personally at all, I try to avoid that as much as possible, because I think that art should be absorbed naturally and peacefully, become part of your process, not hit you in the head and make you swallow it.

Thompson: There is a responsibility that always accompanies all freedom.

Tacha: Yeah, a lot of artists like to deliberately shock, and I really don’t. I try to avoid it as much as possible. I don’t say that all artists who present shocking material have that as a prime concern. They wouldn’t do it unless there was an inner need to do it. Obviously Mapplethorpe’s lifestyle, which he felt very strongly about as a human being, made him make those images, not just the purpose of offending people. On his deathbed, he begged that his images be protected, that they not be censored. Because a man who is dying doesn’t care about shock anymore; he wants his vision to be preserved. And so I really think that the museums should have the responsibility to preserve an artist’s integrity. Now, in the public domain, I don’t think the Serra should have been removed, much as I think it was a mistake to put it there. I think the community should have been consulted, at least informed and educated, before that was put there. I think once it was put there, the artist had a contract, and the committee had a responsibility to protect a public work of art. In France, there is the moral rights law, that you cannot alter or destroy a work of art; it is illegal, because it is artistic patrimony. So a committee that chooses a work of art should think ahead of time what it will feel like to have it there, how the community will respond. They can’t say, we’ll push it down their throat, they’ll learn in time to like it. With the Calder in Detroit, that did happen. But Calder is not Serra, Calder is a person who loved the public, and his work is friendly. So even if at first they didn’t like it, the committee judged correctly that eventually they would like it, whereas Serra is a very authoritarian artist who says, I am right, I see this correctly, I don’t give a damn about your point of view, I make you understand something that are you are unable to see. For me, that is too much for a public artist to do. It’s fine to do it, he has the right to his opinions and to express them, but let’s keep them in the private domain, or at least in a museum. A museum sculpture garden where only the people who want to see it, who are educated in contemporary art, can appreciate it.

But there is no point in antagonizing masses of people when they are not ready for a work. Besides—even I, who love Serra’s work, think that piece was oppressive. It was very beautiful from the sides, but from the front, it just blocked the view so badly. Even if you say the urban landscape in that area of New York isn’t worth looking at, people want a vista, want an openness, you can’t just block their view. So I am on the side of the public, but still I would not want it removed because of the principle involved in art, the permanence of public art. I personally feel that the responsibility of the artist should be there. For instance, O’Neill did not allow the publication of a book until seventeen years after his death because he was afraid it would offend living members of his family. You can protect the public from being offended. You’ve got to respect them. Respect for the other human being is essential.