Art and the Thinking Machine: Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982

Hans Haacke, News, 1969/2008, newsfeed, paper, and printer, dimensions variable [courtesy of the artist, Artists Rights Society and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York]

The computer frees the painter from the weight of sclerotic artistic legacy. Its immense combinatorial capacity facilitates the systematic investigation of the entire field of possibilities. By ridding the artist’s head of clichés, or cultural “mental ready-mades,” it enables the production of assemblages of shapes and colors never seen in nature or in museums. Pictures that we never could have imagined, pictures unimaginable.

—Vera Molnár, 1980

I no longer think very much about the [computer drawing] program’s autonomy. I think of the program as a collaborator.

—Harold Cohen, 2011

Share:

One of the first appearances of digital computers before a mass US audience (and a global one) in the early 1950s was what appeared to be a demonstration of technological prowess. It was, in part, a theater performance. CBS coverage of the 1952 presidential election results prominently featured the first commercially available “electronic brain,” the Remington Rand UNIVAC I, deployed to dazzle and amuse the television audience as it appeared to predict the election results, based upon real-time poll returns.

The machine in the CBS studios, however, was not in fact the UNIVAC I but an elaborate stage prop with panels of blinking lights and meters that convincingly portrayed the idea of an electronic thinking machine rather than the reality of one. The actual UNIVAC, housed in a Philadelphia facility, communicated with the CBS studio via teletype machines.

The UNIVAC I in Philadelphia correctly predicted an Eisenhower landslide victory. But, layering one performance on top of another, CBS producers pressured the computer’s programmers to engineer a more modest prediction in line with recent Gallup polling. Eisenhower’s victory was, however, a landslide. The UNIVAC I had calculated the correct margin of victory to within 3.5 percent. CBS later put a spokesman on the air to confess that “We should have had nerve enough to believe the machine.”

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, comprises the works of about 80 artists making art during the period from the mainframe computer’s emergence into mainstream American consciousness (propelled in large part by that theatrical CBS performance) to the moment when personal home computers began their ascendency in world culture. The CBS broadcast dramatized the themes that artists were to grapple with in the following decades: how to make use of a new all-purpose device that elicited suspicion, fear, fascination, and excitement all at once? What was the appropriate role for human input into this system? Whose reality could be trusted—human or machine?

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, installation view, 2023 [photo: Sarah Applegate; courtesy of LACMA, Los Angeles]

Early uses of computers to make art bore almost no resemblance to contemporary artists’ use of computers, which today relies upon easily accessible and portable machines richly equipped with graphical user interface–based software. Mainframes, by contrast, were room-sized machines in fixed locations that often required specialized engineers or mathematicians to interact with opaque interfaces.

The earliest “computer art,” as it was then called, therefore, nearly always resulted from a collaboration with—or invitation from—major corporations, government organizations, or large universities. Because the work was considered nonessential, artmaking often had to be carried out overnight and on weekends, when the computers were otherwise idle. Edward Meneeley’s 1966 series of untitled electrostatic prints—the result of an invitation to IBM’s New York City headquarters—are bright, monochromatic meditations on texture and visual rhythm. Vertically oriented, they suggest at once architecture, stained glass, and monolithic objects of worship. They are actually made with garbage retrieved from the headquarters’ trash cans—computer punch cards and tapes—processed through a photocopier into abstractions that hint at information, industry, and procedurality. Frieder Nake made his plotter drawings, open squares of bright color in random superimposition, as a graduate student in the mathematics department at the Technical University of Stuttgart (which, in 1967, became the University of Stuttgart), where he had access to appropriate equipment. Even NASA invited such artists as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Lowell Nesbitt to capture, in photographs and prints, the control room that would serve as the theater of the moon landing’s drama.

Despite their circumscribed space of collaboration, the resulting works were often irreverent, probing, sometimes skeptical of the machines and their settings, even as they were enthusiastic in their exploration of formal possibilities. Rebecca Allen’s Girl Lifts Skirt (1974), made under the advisership of computer scientist Charles Strauss at Brown University while Allen was still a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, is a short video featuring an animated line drawing of a girl’s legs as she lifts her skirt to reveal garter belts. Girl Lifts Skirt was Allen’s rebuttal to an all-male engineering environment, in which she felt computers were “inhuman” and in need of a sensual and erotic face. Leon D. Harmon and Kenneth C. Knowlton, working at Bell Labs, produced Studies in Perception I (Alpha Serendipity) (1966, 2023), an array of mathematical symbols printed on paper that coalesce, when viewed from a distance, to form the image of dancer Deborah Hay reclining in the nude. The Bell Labs public relations department refused to be associated with the work until it was covered in The New York Times as a marvel of art and computers’ convergence, at which point Bell Labs insisted upon being credited. Lillian F. Schwartz began her film Pixillation (1970), which was sponsored by AT&T, by laboriously hand-coding a computer with punch cards. After taking two months to produce a few seconds of film, Schwartz abandoned the computer and reverted to hand-painting the 16mm film, but in the aesthetic terms set by the previous programming and computation.

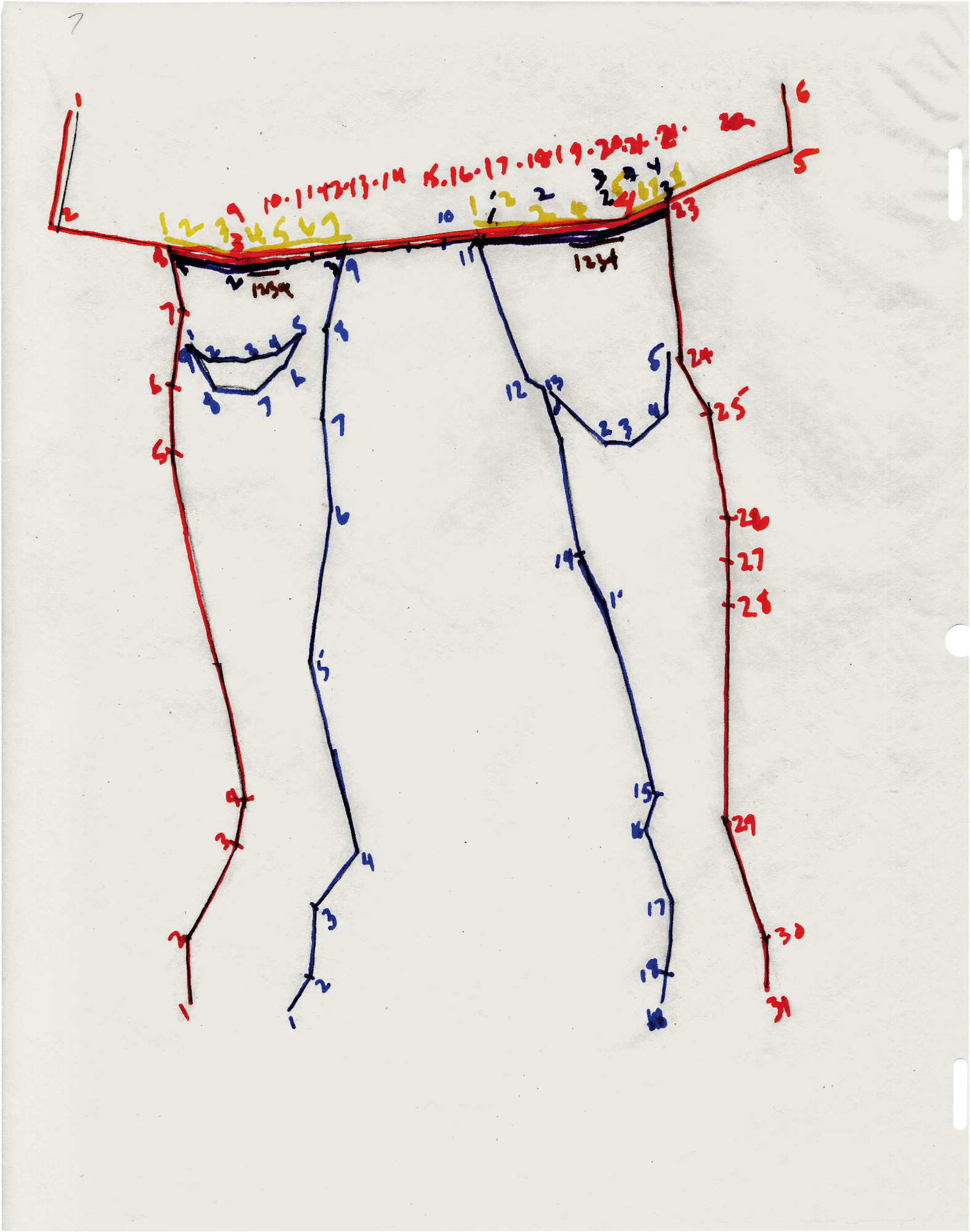

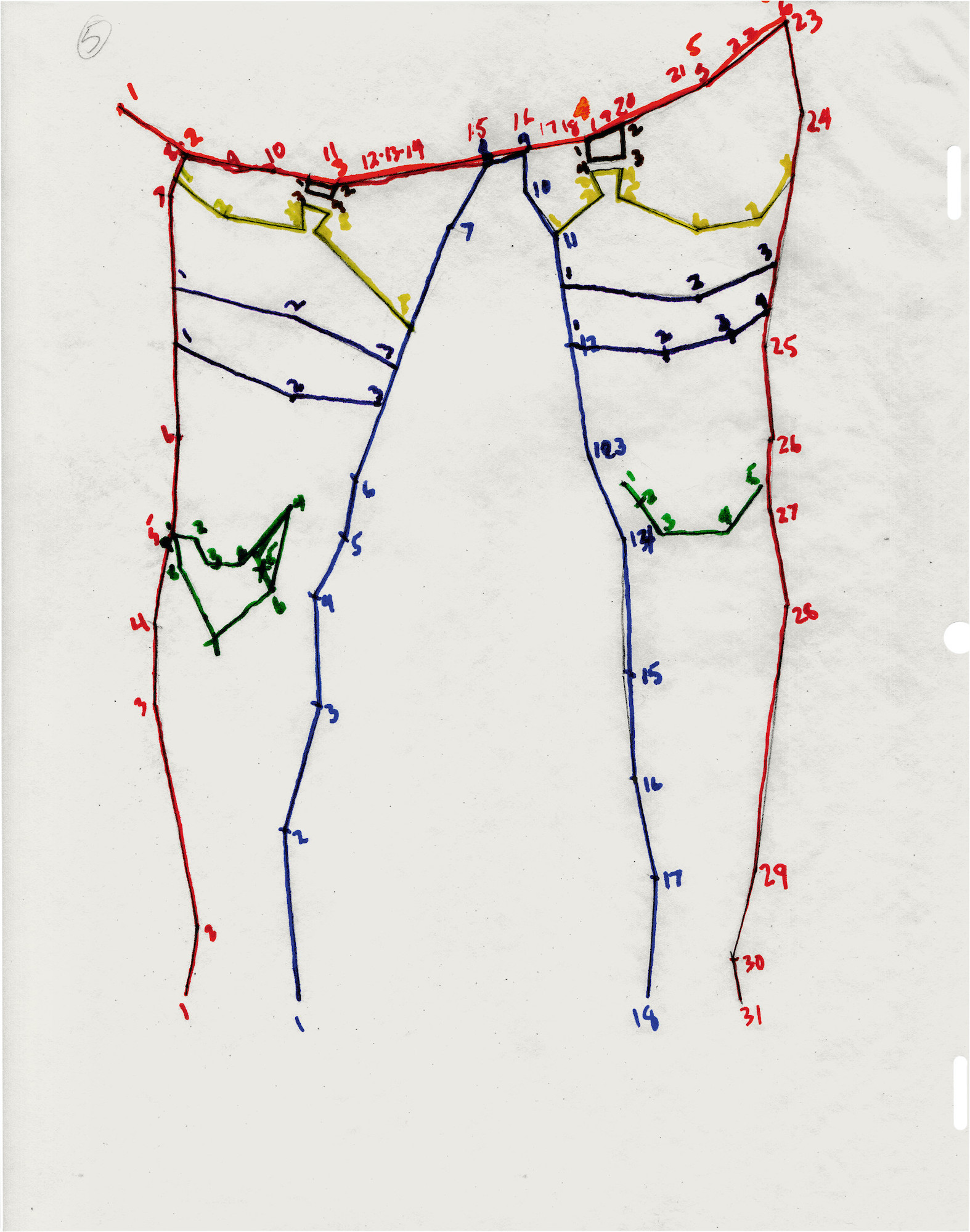

Rebecca Allen, Girl Lifts Skirt, 1974, graphite and marker on tracing paper , 10 x 8 ½ inches [courtesy of the artist and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Rebecca Allen, Girl Lifts Skirt, 1974, graphite and marker on tracing paper , 10 x 8 ½ inches [courtesy of the artist and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

These artists leveraged their connections to major institutions but responded with ambivalence, complexity, and impulses of resistance. Still, if their work was enabled by major businesses, then it was often regarded with suspicion by art institutions. Computer art of the 1950s and 60s inhabited an uneasy position amid art, science, and the military industry that birthed it. Because it was largely ignored, if not scorned, by many fine art gatekeepers, the door was left open to work by engineers, mathematicians, and programmers who did not think of themselves as fine artists at all.

Ben F. Laposky—trained as a mathematician and draughtsperson—began making his series of undulating oscilloscope light abstractions in 1950, after reading an article in Popular Science on using television testing equipment to generate decorative light patterns. The works met a cautious reception by some critics, who couldn’t be sure if the works were art at all, but who could defend them based upon the most conventional notions of composition and beauty. A. Michael Noll, a Bell Labs engineer, programmed a mainframe to approximate Piet Mondrian’s Composition in Line (1916–1917) by feeding the machine specific parameters of line length and spatial arrangement. The result fails to capture the spatial solemnity of the original Mondrian. Ironically, most viewers, when asked to compare the two, assumed Noll’s was the hand-painted original, as most viewers associated unevenness and awkward composition with a human touch. Hiroshi Kawano was neither an artist nor an engineer but an aesthetic philosopher intrigued by the theories of poet and philosopher Max Bense’s information aesthetics. Bense aspired to a quantitative assessment of art based upon the information it could carry. Plotting out a grid on sheets of continuous feed paper (the example included in Coded is almost six feet long), Kawano assigned each square a value based upon the values of a “probability matrix.” He then hand–colored each square with colored pencil. The result is part Persian rug, part Boogie Woogie–era Mondrian.

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, installation view, 2023 [photo: Sarah Applegate; courtesy of LACMA, Los Angeles]

The computer amplified, if not enabled, numerous variations of such rules-based art, unencumbered by traditional methods, or even by individual artist psychology. Describing a turn that Manfred Mohr dubbed “statistical thought,” the artist remarked on how the computer compelled artists to move beyond spontaneous expression to “formulate an original idea in a program containing every possibility for that idea.” Artworks could thereby embody parameters of an entire field of potential expressions rather than a particular pictorial, sculptural, or kinetic expression. Against the backdrop of abstract expressionism’s romantic subjectivity, the new computer art was purposefully systematic, cool, and rational.

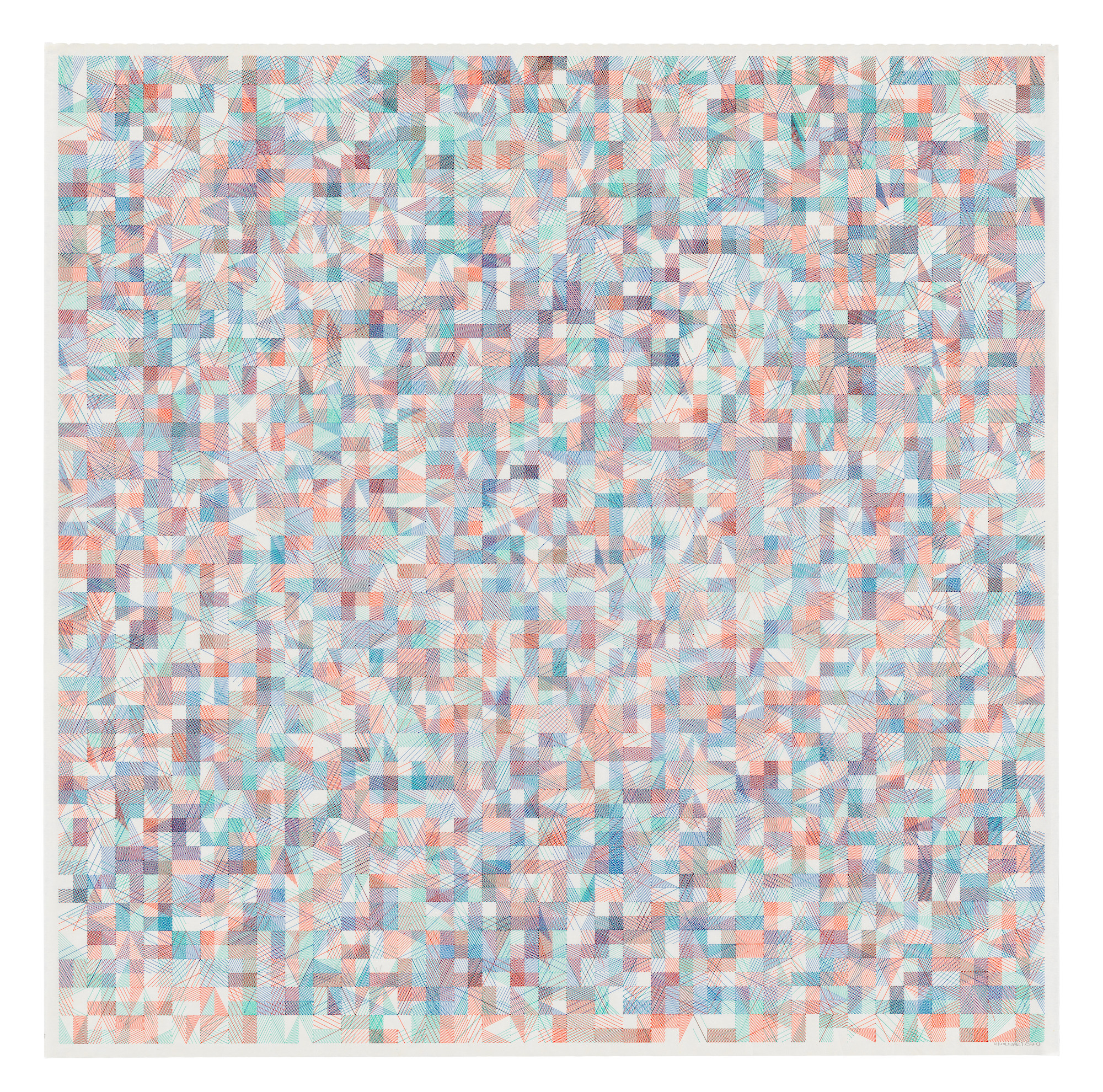

Such artists as Alison Knowles and Vera Molnár pushed these ideas to their logical extremes. Knowles’ House of Dust (1967) consists of a FORTRAN program that cycles through and produces all possible combinations of a specific sentence structure, some of whose parts are fixed, others of which vary. “A house of dust / in dense woods / using all available light / inhabited by one man.” “A house of snow / in heavy jungle undergrowth / using candles / inhabited by people who love to read.” And so on in seemingly endless variation. Molnár’s visual art practice paralleled Knowles’ work in poetry. In À la recherche de Paul Klee (1970), Molnár plotted grids filled with diagonal lines randomly angled, spaced, and colored. The resulting visual field bears the order of a rigid underlying structure overlaid with thrumming visual cacophony.

Vera Molnár, A la recherche de Paul Klee, 1970, original plotter printer drawing, 28 ½ x 28 ½ inches [courtesy of the artist and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Similar statistical thought was evidenced in works made without the use of computers, positing the intriguing thesis that computer technology can be understood not only as tool but as metaphor and catalyst available throughout the culture. Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes is a case in point. The work consists of clean, white maquettes of every possible combination of three or more edges that might form a six-sided cube, short of a complete cube.

Notions of repeatable, modular programs were not unfamiliar elsewhere in midcentury high modernism. The International Style in architecture and concrete art sought to prioritize forms free of individual psychologies and therefore putatively free of individual prejudices. Translated into computer terms, the result was a prioritizing of rules, algorithms, and numerical randomness over representation, perspective, and indwelling intuition.

Donald Judd’s Wall Progression (1971) uses the Fibonacci sequence to position a series of rectangular blocks along a span of space. Analívia Cordeiro’s dance work M 3×3 (1973) comprises a dance performance and the video of that performance, which are both generated by the same computer program, written in FORTRAN by Cordeiro herself at age 19. Harold Cohen’s AARON artificial intelligence software produced drawings based upon problems posed to it by the artist, who interceded only to enlarge and print the results. These artists sought to reduce or eliminate the telling hand of the artist in favor of the authorship of the computer.

By chance, Coded debuted at roughly the same moment as non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and generative AI artmaking platforms such as Midjourney have once again prompted debates among artists, critics, and technologists on questions of authorship and technology. This survey provides indications of the range of approaches—playful, political, philosophical—that artists have tried in the past in response to similar questions and, perhaps, offers tantalizing clues to where recent experiments may lead.

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, installation view, 2023 [photo: Sarah Applegate; courtesy of LACMA, Los Angeles]

Cinqué Hicks is a Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant-winning critic and writer who has written for Public Art Review, Art in America, Artforum.com, Artvoices, and other national and international publications. He has served as senior contributing editor of The International Review of African American Art and as interim editor in chief of ART PAPERS. He was the founding creative director of Atlanta Art Now and producer of its landmark volume, Noplaceness: Art in a Post-Urban Landscape. He is currently a contributing editor for ART PAPERS.