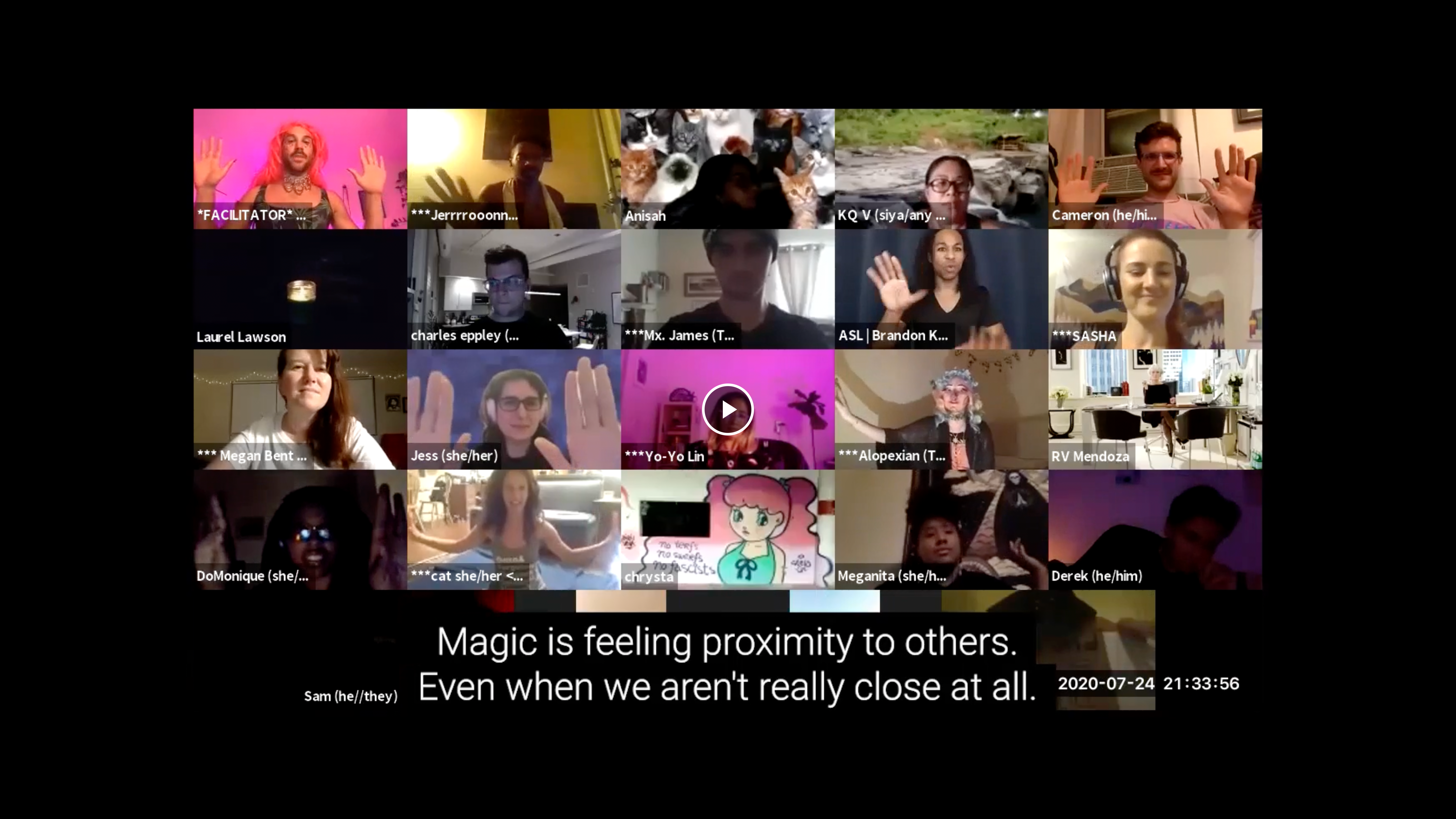

Critical Design Lab, Remote Access, 2022, Zoom screenshot [courtesy of Critical Design Lab, and Kevin Gotkin]

and we were dancing

Share:

I. The world was ending and we were dancing.

It was spring 2020, and three of us (with the dog) were wearing cheap, colored wigs, dancing in our living room to a set by DJ Who Girl. We were logged in to the first Remote Access party organized by Critical Design Lab, on a Zoom grid, among other participants in their homes, sharing a common virtual space. That early pandemic moment felt like a kind of rupture—where the walls of our apartment collapsed outward, engulfing the spaciousness of those many other rooms.

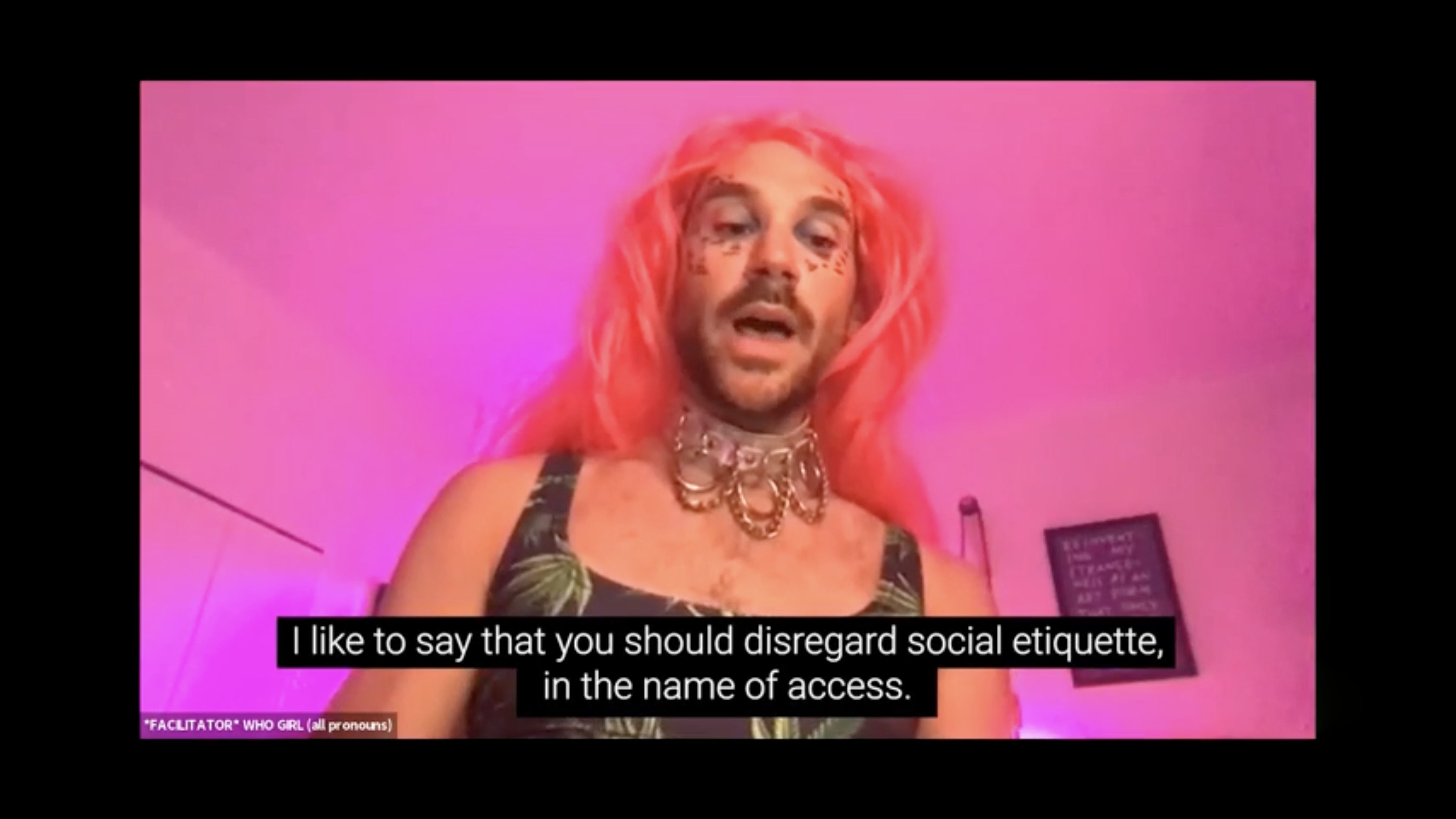

Critical Design Lab, a collective working across disciplines and institutions, describes the Remote Access series as “crip nightlife” practice (Crip, slang for the word cripple, is a term (re)claimed by some disabled people and movements; sometimes also used as a verb.) Since March 2020, the collective has organized virtual parties hosted by Kevin Gotkin (DJ Who Girl) and featuring a range of disabled artists. The parties are structured by access, with one participation guide emphasizing that “orienting ourselves towards access is not prefatory. It’s not a delay.” The gatherings incorporate interpreters, captioners, sound describers, and access doulas—an extension of the support role most commonly thought about in the context of childbirth, and akin to the community project “What Would an HIV Doula Do?” Each party has included a thorough participation guide that details the itinerary, access roles, and safety notes. The safety notes, which aim for de-escalation, cite inspiration from Safe OUTside the System Collective’s Safe Party Toolkit, first published in 2007 by a collective of “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Two Spirit, Trans, and Gender Non Conforming” people of color, underscoring how Critical Design Lab is informed by other radical spaces, and that a disability justice lens is inherently intersectional.

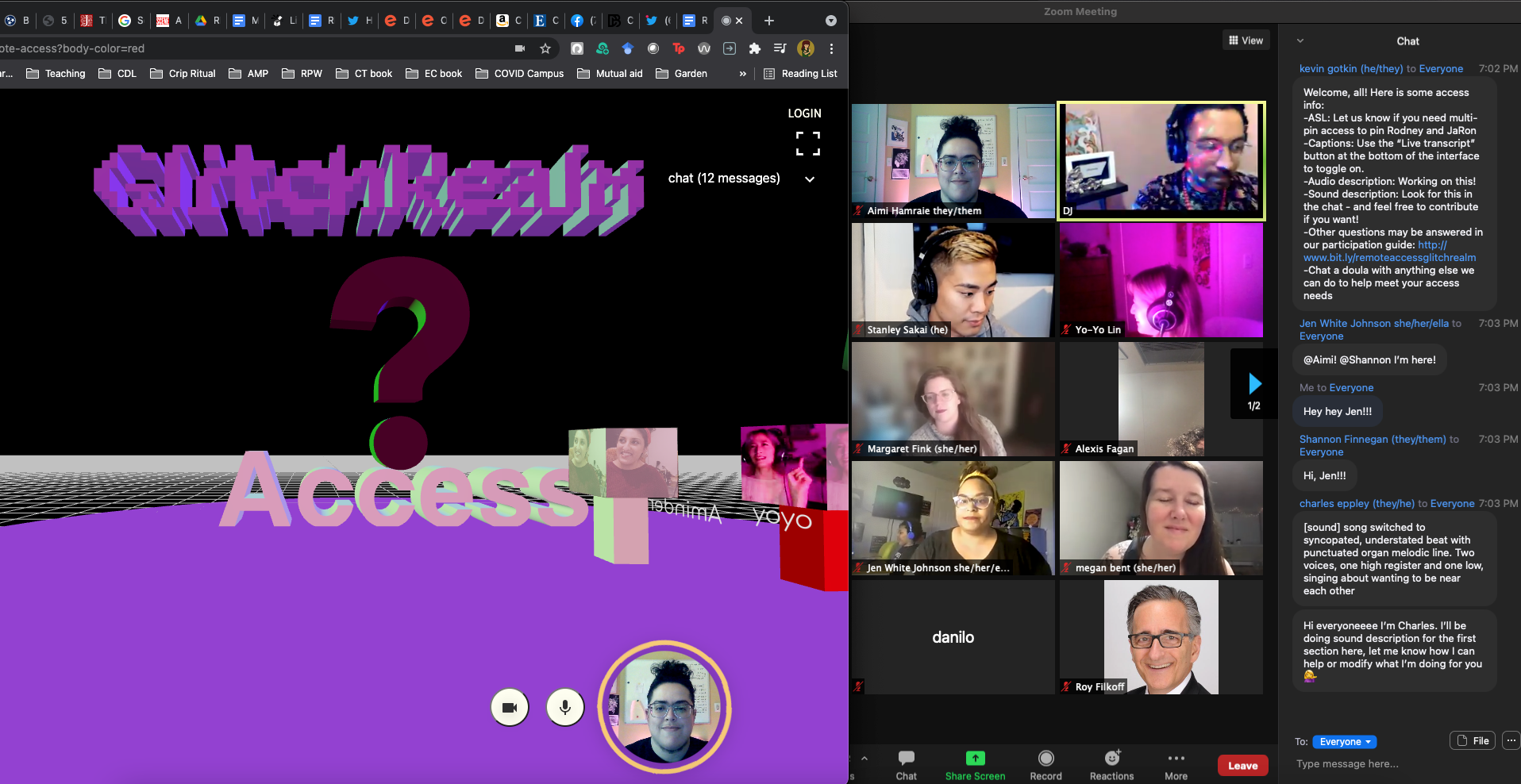

Critical Design Lab, Remote Access, 2022, Zoom screenshot [courtesy of Critical Design Lab, and Kevin Gotkin]

Nightlife spaces have always been inaccessible for many people, but during that first pandemic spring of “flatten the curve,” many more faced a new impossibility of gathering in person. In this moment, many venues scrambled to adapt their communities to the new virtual reality. Nightly parties—like ones hosted by Club Quarantine, a gay club based in Toronto—popped up and found global audiences. Whereas disabled folks previously found themselves often denied access to even basic virtual accommodations across settings, some of them suddenly were the most equipped for the abrupt switch to virtual spaces. It must be stated that, from the beginning, the construction of “stay at home” as a newly common experience relied on assumptions which erased both those whose labor was not possible from home (many of whom were then deemed “essential”) and those for whom staying home was a necessity, not a novelty.

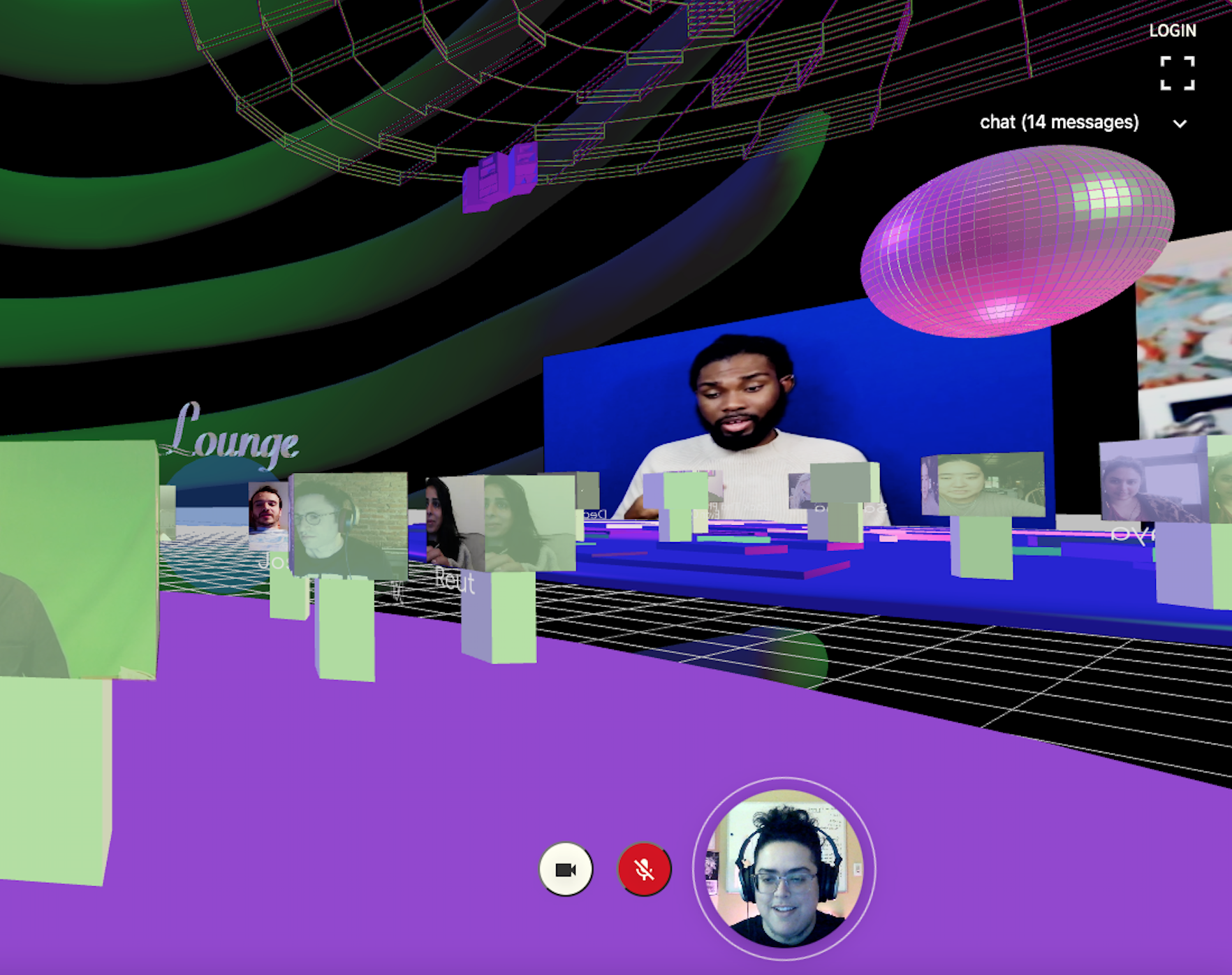

Even as Zoom novelty faded, along with the mainstream commitment to risk reduction, Remote Access parties continued. They have been presented in collaboration with organizations including the Society for Disability Studies, Allied Media Conference, and CultureHub. The parties have featured artists including Yo-Yo Lin, Shannon Finnegan, Pelenakeke Brown, Ezra Benus, moira williams, and JJJJJerome Ellis. Each gathering reaches beyond the borders of a dance party and often corporate platforms to incorporate live visuals, incantations, karaoke, and virtual backgrounds for participants. In April 2021, I even DJ’d a party under my pandemic-born identity of DJ Queer Shoulders, hosted on the 3-D meeting platform Atrium and on Zoom. Participants on Atrium explored a virtual world of pinks and purples that included a lounge, karaoke, and a dance floor where keystrokes made your avatar jump to the music.

II. The world was ending and we were dancing.

It was fall 2021, and we were gathered at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, looking over the East River, watching ferries pass while bracing for a potential and unseasonal storm. Levani, in collaboration with Rave Scout Cookies, invited us to Levani’s Room: ecdysis, a “transdisciplinary pollination between rave, public art, and activism.” The title conjures the natural process of shedding old skin, and it references the artist’s ongoing immersive multimedia installations, which have been shown at venues including the 2020 SPRING/BREAK Art Show, where Levani’s Room: HOME featured liquid mirror panels with the logos of underground venues, a soundscape, and a performative meal sharing. The program occurred as part of the 2021 Socrates Annual, Sanctuary, to activate Levani’s sculpture 127.1 BPM (for my dancing peers); it featured DJs Manu Miran, Body Double, and DJ Witchcft.

I was curatorial assistant at Socrates during the process of selecting that year’s artist fellows, and I distinctly remember Levani—in a black T-Shirt reading GENDER, with the embedded word END emphasized—talking about “parks being the new clubs” during the pandemic. Indeed, as we learned about the relative Covid safety of outdoor gathering, many took to hosting parties in parks—large and intimate, permitted and not.

Levan Mindiashvili, Levani’s Room: ecdysis, installation detail, 2022 [photo: Sofie Kjørum Austlid; courtesy of Socrates Sculpture Park]

Levan Mindiashvili, Levani’s Room: ecdysis, installation detail, 2022 [photo: Sofie Kjørum Austlid; courtesy of Socrates Sculpture Park]

In Brooklyn, Manushka Magloire, Emily Anadu, Briyonah Mcclain, Michael Oloyede, and Cyrus Aaron founded The Lay Out. Hosted in Fort Greene Park during summer 2020, the gathering “was just about Black bodies together taking up space,” as Anadu told The Cut. This reclamation of outdoor space is significant in the context of increasingly gentrified neighborhoods and boroughs, and within a summer of sustained street protest that followed the death of George Floyd. Magloire expands: “In that park there is a clear line of demarcation, and this is why we position ourselves, front and center at the top of that hill. You’re going to see us, you’re going to hear us, and you’re going to feel us as we are here. The park is an open shared space. Air is free.”

At Socrates, Levani’s sculpture was inspired by bringing underground parties into the open air—creating a new kind of commons, a new kind of sanctuary. The sculpture, titled after a particularly danceable beat per minute, is a portal made of polished stainless steel, lab hardware, lights and, importantly, sound, which was produced in collaboration with Bryce Hackford and dr. fruit. Especially at ecdysis, the sculpture served as an opening to another kind of space—a queer sanctuary inside a public city park that began as a landfill.

Levan Mindiashvili, Levani’s Room: ecdysis, installation detail, 2022 [photo: Sofie Kjørum Austlid; courtesy of Socrates Sculpture Park]

III. The world is ending; let’s dance.

The Remote Access parties and Levani’s 127.1 BPM represent new, expansive ideas of the commons where queer, trans, immigrant, and disabled communities have gathered, and will gather, transgressively. These parties are made possible by deep collaboration, with both projects rejecting a single curatorial authority to, instead, be structured as platforms highlighting (and paying) other artists. They share and gather many kinds of resources—money, space, time, information. Each gathering navigates complex institutions and environments—physical and virtual, within the “art world” and outside it—to present visions and intentions grounded in community.

As they inhabit these potentials, both practices also reflect the liminality of the commons. Levani, for example, reflects upon the fragility of those underground clubs, many of which shut down permanently during the pandemic. Levani’s work, in turn, reflects this precarity and works to counter it by bringing the spirit of these places to gallery, public, and outdoor space. Critical Design Lab and the Remote Access parties fully embrace the prevalence of glitches in virtual space, with past themes including “Witches and Glitches” and “GlitchRealm.” One of the guides states that participants are “always invited to experience the glitches for the often beautiful things in themselves,” and encourages us to “imagine the symphony of all of our computer fans singing all at once.” This embrace is purposely opposed to the static and stable, connected to disability/crip aesthetics and broader liberatory claimings of the glitch, considered in such texts as Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (2020).

There will be no “post” pandemic. We will continue to see how these kinds of expansive “commons” morph and adapt. Some clubs have closed for good, but many have reopened and have, in turn, become even more inaccessible. The virtual has been normalized, but many people still prefer “IRL,” an impulse that ignores ongoing risks of the pandemic, especially to those who remain most vulnerable. Even post-vaccines, the threat of Covid remains, and particularly so for disabled, immunocompromised, and other marginalized communities. Still, many people—eager for normalcy and crowded, in-person parties—seem to be ignoring or normalizing this danger. Will disabled communities, for example, be ignored as quickly as they were tapped for their insights?

Critical Design Lab, Remote Access, 2022, Zoom screenshot [courtesy of Critical Design Lab, and Kevin Gotkin]

What can we learn from this moment, in which the force of the pandemic has been a common (albeit disproportionate) determinant? I think of The Lay Out and its collaboration with One Love Community Fridge to fund food for folks in Clinton Hill and Fort Greene, a gesture linking basic needs to existing spaces of culture that seems critical for commons-building. I think of the continuing Remote Access parties, with their now-global reach across realms, platforms, geographies, and many dance floors. I keep returning to their guides as living tools for sharing many kinds of space, practicing accountability and abundance, and bringing folks into a space patiently.

And what about the plural commons? Commons are at their best when they push against universalizing impulses. Liberal fantasies of “open to all” often just reinscribe dominant power structures, making commons that center specific communities especially potent—whether they consist of disabled folks at Remote Access parties, queer folks of color in Levani’s Room, or Black Brooklynites at The Lay Out.

Indeed, dance floors—in clubs, in parks, in living rooms—will remain potent places of connection and joy, but many will still be inaccessible places where harmful structures and behaviors can be present. It is in our liberatory interest to care for them as commons expansively and with intent. I am grounded in the knowledge that the communities—my communities—ones that built and nurtured spaces like those imagined by Levani and the Critical Design Lab, will continue to innovate, celebrate, and practice new and existing ways to express care.

With thanks to Michael Mandiberg, whose work and exhibition Timeframe at Denny Dimin Gallery first inspired me to write about Remote Access in my catalogue essay “labor/record.”

Critical Design Lab, Remote Access, 2022, Zoom screenshot [courtesy of Critical Design Lab, and Kevin Gotkin]

danilo machado (he/they) is a poet, curator, and critic living on occupied land who is interested in language’s potential for revealing tenderness, erasure, and relationships to power. Their writing has been feature in Hyperallergic; Poem-A-Day; The Recluse; GenderFail; No, Dear; artcritical; and TAYO Literary Magazine,as well as alongside exhibitions at Miriam Gallery, CUE Art Foundation, Real Art Ways, and elsewhere. machado is producer of public programs at the Brooklyn Museum and curator of the exhibitions Otherwise Obscured: Erasure in Body and Text (Franklin Street Works, 2019–2020), support structures(Virtual/8th Floor, 2020), and We turn (EFA Project Space, 2021).