A Living Presence + and the body, Felix, where is it?

“Untitled”

1991

Billboard

Dimensions vary with installation

Mettenwylerstrasse 1, Luzern, Switzerland. 1 of multiple billboard locations as part of the exhibition Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Specific Objects without Specific Form. Fondation Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland. 21 May – 25 Jul. 2010. Cur. Elena Filipovic [shown]; 31 Jul. – 29 Aug. 2010. Cur. Carol Bove. [One of three parts. Additional parts: Wiels, Brussels, Belgium. 16 Jan. – 2 May 2010; MMK Museum fur Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, Germany. 28 Jan – 25 Apr. 2011]. Photographer: Mark Niedermann.

© Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Courtesy of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Share:

A Living Presence

+

and the body, Felix, where is it?

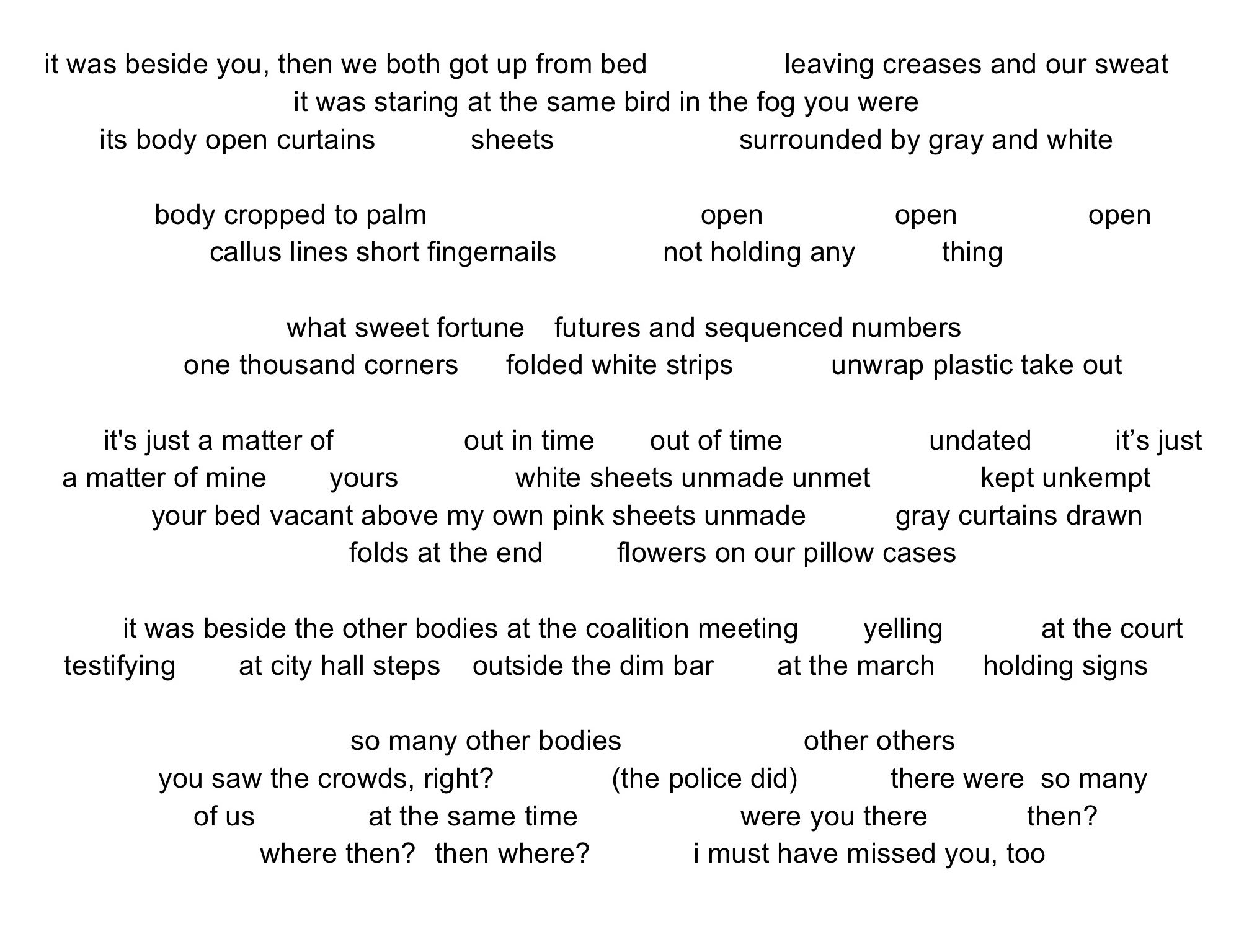

The following texts are the result of a collaboration between Re’al Christian and danilo machado. Christian’s essay and machado’s poem produce a dialogue that—in content and form—responds to the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres. These interwoven texts can be read separately or as one dialogue in two voices.

no title no body above white ad space available 718-783-7048 above village restaurant windows red cursive neon above

customers passengers pedestrians passing cars and bikes which side of the road dotted yellow white crosswalk triangles

There is a distinction between memorials and monuments that often goes unaddressed. The two words are etymologically related to memory and sometimes used interchangeably, or in proximity. Although a monument celebrates a noteworthy memory—a historical moment, an achievement, a victory—a memorial commemorates loss: an elegy set in stone. A rupture, an ideological rift, exists between memory and history. How we remember the past, and by extension how we choose to commemorate it, can be at once synchronous and contentious. History as a discipline exists in this dualistic space, as it attempts to reconcile narratives of exceptionalism and oppression. With each monument that has been erected, we must ask whose history the structure embodies, and what histories are buried when a monument is constructed?

How do we memorialize an absent body? In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us may be asking this question. We’re dealing with a particular kind of grief, a collective mourning, one that is new for some and painfully familiar for others. It’s difficult to conceive how we mourn and memorialize people affected by our current pandemic. Many artists and writers have offered poetic responses to the question of what a COVID-19 monument might look like, while also assessing the risk of erasing disproportionately affected communities in the resurgence and aftermath of the disease. As we contemplate and rewrite the politics of touch, intimacy, mourning, and closeness, it seems only natural that the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957–1996) has taken on new resonance. Known for his minimalist installations and sculptures, the artist was no stranger to the question of how to memorialize absent bodies. Working at the height of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, he did not propose a definitive answer to this question, but his work is an integral part of an ongoing reflection upon the poetics of commemorating the sudden absence of innumerous bodies.

no title body below cylinders of exhaust and pointed roofs and walls and more square windows and sky sky sky

no title body eye level bigger than your body subway stationed among arrows and announcements past which

“Untitled” (For Jeff), 1992, Billboard, Dimensions vary with installation, 327 Woodstock Road, Belfast, Northern Ireland. 1 of 24 outdoor billboard locations throughout Belfast, with 1 indoor location, as part of the exhibition Felix Gonzalez-Torres: This Place. Metropolitan Arts Centre, Belfast, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom. 30 Oct. 2015 – 24 Jan. 2016. Cur. Eoin Dara.

© Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Courtesy of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

stop which car which seats empty clocks reset no title no body hospital college museum dallas berlin são paulo multiple public

venues no titles no bodies rectangle between trunks at slight angle or green road bushes and grass growing unsymmetric

Writing in 1994, bell hooks remarked that Gonzalez-Torres’ work embodied the “aesthetics of loss,” losses that were, for him, quantified but incalculable. The artist’s biography is almost inextricable from the way we understand his process. His works exist as both public monuments and private memorials, structures built around silence, familiarity, and interaction. Rather than figures, his “portraits” of loved ones lost to AIDS depict traces of their absence. Installations of objects such as cellophane-wrapped candy, fortune cookies, and stacked sheets of paper enact epic theaters, where objects were made to be touched, taken, and experienced. The artist’s snapshot photographs could act as memorials in their own right. With images of empty, rumpled beds still showing the impression of now-absent bodies, and of vast skies punctuated by lone birds, he represented moments of absence that we often take for granted. His seminal billboards appropriate a familiar visual format and transform it into a site for memorial. The billboard “Untitled” (For Jeff) (1992), for instance, shows a single hand resting on a white background, its palm faced outward. There is no context or inherent meaning that can be derived from such a spare photograph. As with much of Gonzalez-Torres’ work, the subject has been disembodied. The image acts as synecdoche, a portrait not of an individual but of a collective.

In interviews, Gonzalez-Torres maintained that his partner, Ross Laycock, was the sole public of his artistic practice: “The rest of the people just come to the work.” Gonzalez-Torres met Laycock in 1983. The two were together until 1991 when Laycock died of AIDS-related complications, five years before Gonzalez-Torres’ own death. Laycock is often a suggested presence in the artist’s work, as subject and audience, though physically he remains absent and bodiless. But in a 1984 snapshot, we see him standing against a pink wall, a pink-and-white-striped curtain cascading behind him. He’s shirtless, grinning, and looking right into the camera (in another shot he turns away from the camera, still smiling). He looks strong and rugged—it’s difficult to imagine him sick, losing weight and hair. In her essay “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” hooks considers how the snapshot functions as an altar: “Fictively dramatizing the extent to which a photograph can have a ‘living presence,’ [Toni] Morrison describes the way that many black folks rooted in Southern tradition once used, and still use, pictures. They were and remain a mediation between the living and the dead.” Gonzalez-Torres’ snapshot of Laycock serves a similar function; as a requiem, it represents a solitary moment suspended in time, both perfect and imperfect, candid and confined.

no title no body once or twice on bricks many white or brown no title body framed floated cushion ads in leaves or concrete no

title no body ten men came no body dripping light silent portrait snapshot no body go figure no body public memorials to no body

One of the most well-known billboard artworks Gonzalez-Torres created can be interpreted as a portrait of Laycock, “Untitled” (1991), and makes use of a photograph, transforming it from a vernacular medium into a monument. The billboard, first exhibited in 1992, shows the impressions of two bodies left on the sheets of a clean white bed. At the height of the AIDS pandemic, and the year after Laycock died, it can serve as a powerful allegory for the multitudes lost during the crisis. In the photograph, the linens are rumpled and pulled back, the pillows dimpled by the heads of the bed’s recent inhabitants. But these are more than faint impressions. The bed seems scarred by these invisible bodies. One could make different associations with this photograph—love, loss, sleep, restlessness. As with many of his portraits, Gonzalez-Torres did not include a body, and the absence depicted remains ambiguous. The lovers are invisible but not bodiless. They are the same, not in appearance but in the space they occupied. Bodiless duos often figured in Gonzalez-Torres’ work. In “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) (1991), a pair of adjacent analogue clocks slowly fall out of sync with each other over time and can be perpetually reset. In “Untitled” (March 5th) #2 (1991), two light bulbs hang together, suspended by a cord. They shine equally bright, but inevitably one bulb will burn out before the other—and similar to the clocks in “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) 1991, when a bulb burns out, it should be replaced immediately. The work becomes infinite. The bodies in “Untitled” (1991) are similarly connected, tethered to each other and absent from our gaze.

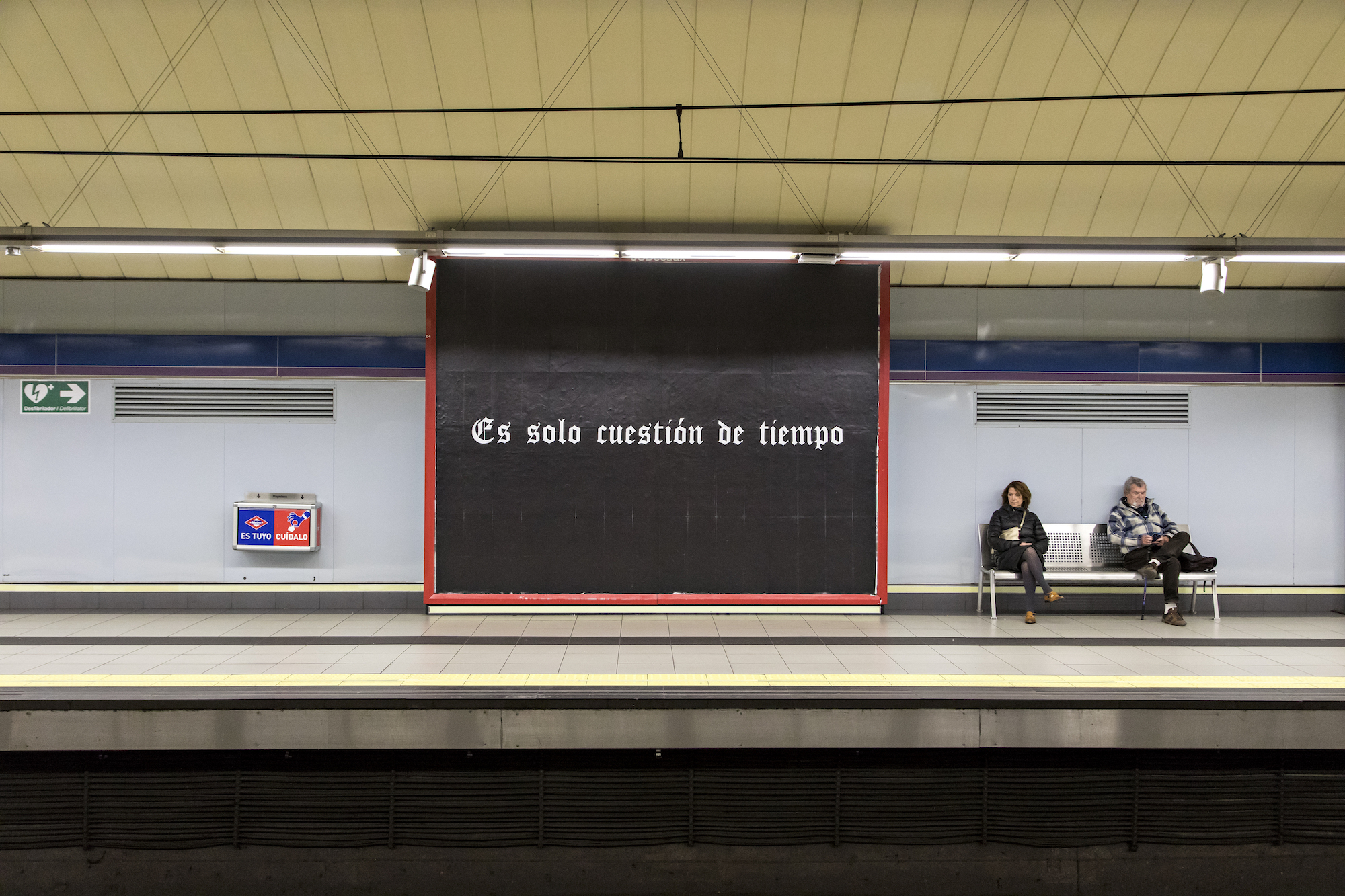

The temporality of these installations touches on what it would mean for a monument to exist impermanently, for its presence to fade, or for its existence in real and imagined publics to be confined to a specific time and place. The phrase “It’s just a matter of time” form the content of “Untitled” (It’s Just a Matter of Time) (1992), one of Gonzalez-Torres’ earliest billboard works. This work, like many other billboard works, is installed in a minimum of six locations and has been included in multiple exhibitions since its creation. The ominous phrase appears in a white gothic typeface on a black background, raising a number of questions: Who is the subject? The speaker? Whose is the voice? The phrase has a unique temporality, at once infinite and ephemeral. No context is provided, so we must make our own associations. As a billboard the installation itself is only temporary, so the message is also self-referential—it anticipates its own disappearance. Our proximity to the work is likewise impermanent. It’s just a matter of time. The tether inevitably will break. If we return to the snapshot of Laycock enshrined in that pink room, we might think about how an object, something we hold close, carry with us, use again and again, bears traces of memory. If we lose that object, the memory we associate with it can still remain.

Gonzalez-Torres’ work treads a line between public and private, absence and presence, life and death. In their publicness, his works take on the role of monuments, addressing intimacies both individual and collective. But in referencing vernacular forms—billboards, snapshots, headlines—the monuments become part of day-to-day lives. This soft presence is antithetical to the idea of a monument, to the sovereignty a monument inherently claims the moment it is consecrated. As monuments serve to enshrine a particular ethos, the narratives behind them are assumed to be irrevocably rooted in our cultural memory. As new monuments are built and old ones torn down, however, the systems of power that these forms represent seem ever more porous. Like a snapshot, these structures are not fixed, but fluid—for better or worse, they capture moments worth remembering, albeit imperfectly.

stack no lack no title no body only sole certified legal tender measured purchased distances specific foundation requests

obligations clauses causes no title living body archive body presence installed waterproof coat glue scaffold tether lasting

“Untitled,” 1995, Billboard, Dimensions vary with installation, 1 of 6 billboard locations throughout Mexico City, Mexico, as part of the exhibition Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Sonora 128, Mexico City, Mexico. Jan. – Feb. 2018. © Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Courtesy of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

“Untitled” (It’s Just a Matter of Time), 1992, Billboard, Dimensions vary with installation, 1 of 12 outdoor billboard locations throughout Madrid as part of the exhibition ARCOmadrid. Feria Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo. Madrid, Spain. 2 Feb. – 1 Mar. 2020. © Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Courtesy of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

danilo machado is a poet, curator, and critic on occupied land interested in language’s potential for revealing tenderness, erasure, and relationships to power. A 2020–2021 Poetry Project Emerge-Surface-Be Fellow, they have had writing featured in Hyperallergic, The Brooklyn Rail, artcritical, and TAYO Literary Magazine, among others. machado curated the exhibitions Otherwise Obscured: Erasure in Body and Text (2019) and support structures (2020), and co-founded/co-curates the reading series Maracuyá Peach and the chapbook/broadside fundraiser already felt: poems in revolt & bounty. They are working to show up with care for their communities.