Amy Sherald: Pictures of American Life

Amy Sherald, “The Bathers”, 2015, Oil on canvas, 74 x 72 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

In February 2018, Georgia-born and Baltimore-based artist Amy Sherald received the David C. Driskell Prize, given annually by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Less than a week later, the highest profile commission in the artist’s career—the official portrait of former First Lady Michelle Obama—was unveiled. Sherald’s name was instantly ubiquitous, with features in major national newspapers and art blogs alike. In April 2018, as interviews with Sherald and features about her continued to stream across headlines, former ART PAPERS Editor and Artistic Director Victoria Camblin spoke with the artist about living and working in not-New York, the power of being mainstream, and how making art is a damn job.

Share:

Victoria Camblin: Interviews don’t often ask about your connection to Georgia. What was your experience like in Atlanta, specifically as a young artist?

Amy Sherald: Well, I would like to say that I was an artist when I lived there, but now that I actually am a working artist, I know I wasn’t an artist. I have really fond memories of college and coming into myself. I made lifetime friends there, worked as a bouncer at different night clubs—you know, I was just your basic 20-something-year-old trying to smoke Newports every now and then and hang out at Club 112 (laughs)! Atlanta’s still one of my favorite cities—it’s a little bit overpopulated for me now, because all the side streets that used to be shortcuts to avoid traffic are full of traffic and characters now!

VC: Oh, I know!

AS: It’s grown exponentially, but some things have stayed the same— Eats on Ponce is still my favorite place to go. I’ve always been a city mouse, so I’ve always lived in apartments like Station Square in Reynoldstown. It’s still there and probably the cheapest place to live in Atlanta.

VC: That’s around the corner from our office. They’ve raised the rents on all those old buildings, though.

AS: Oh, really?

VC: When I first moved here I lived in that stucco hacienda on Ponce at Seminole—you know the one, it’s yellow and falling down? In my two years there the rent went up, like, 300 dollars. It’s funny—that seems like such a generic complaint (laughs), but it’s what happens. So, you were an undergrad at Clark Atlanta University at that time, right?

AS: Yeah, I was at Clark—I didn’t even mention college! Clark was great. I spent most of my time on Spelman’s campus because I was an art major, and when you’re a painting major, you go to Spelman. I was coming from Columbus, Georgia, where I had a highly sheltered background. So, when I first arrived there, within a year and a half I had shaved my head, got a labret piercing, a tattoo—you know, going through my Goth kinda grunge phase, which was not exactly cool on a historically black college [campus] at the time. But that was my tribe.

Amy Sherald, “Freeing Herself Was One Thing, Taking Ownership of that Freed Self Was Another,” 2015, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

Amy Sherald, “Saint Woman,” 2015, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

VC: Can you say a little bit about that transition you mentioned, between thinking you’re an artist when you’re young, then realizing once you become a working artist that that’s not what that was? Particularly as someone who has recently completed an extremely high-profile commission?

AS: When I came out of college, I didn’t really understand the academic aspect of art-making yet. Then I started working with Arturo Lindsay, my professor from Spelman, as his assistant, traveling and installing shows for him and things like that.

I got a lot of my characteristics from him—what it actually meant to be an artist, you know—by working in his studio and watching his process and everything that went into it, from the reading to the art-making. He sent me to Panama to install this show when I was 24, and I did it successfully without him. He had something to do in Germany or something like that—and it was a big deal. I remember the other part of it: having to be the person at the opening, and socializing. I remember having a conversation with an ambassador, and he wanted to have a conversation about it, and I was running away from engaging with people (laughs). And, you know, [I] just kind of disappeared, which is something I absolutely wouldn’t do now. In those ways I have matured, yes. I’ve always been painfully shy and had to grow out of that, as well.

Now, I’m a grown-ass woman, and I wake up and work. Now it’s a job. It’s not about inspiration, or me feeling like I can’t do it because I broke up with my boyfriend, or, you know what I mean. That can’t keep you away from it because it’s how you feed yourself. I’m really working on leaving a legacy, and that becomes who you are. If I’m not painting after a couple of weeks I start to get depressed, and I’m wondering “Why am I depressed? I don’t understand.” Then I realize “Oh, yeah, it’s because I’m not working.” I definitely don’t feel like I am anybody without it, which sounds crazy. I don’t have a purpose; I don’t have a daily purpose unless I am working towards this goal.

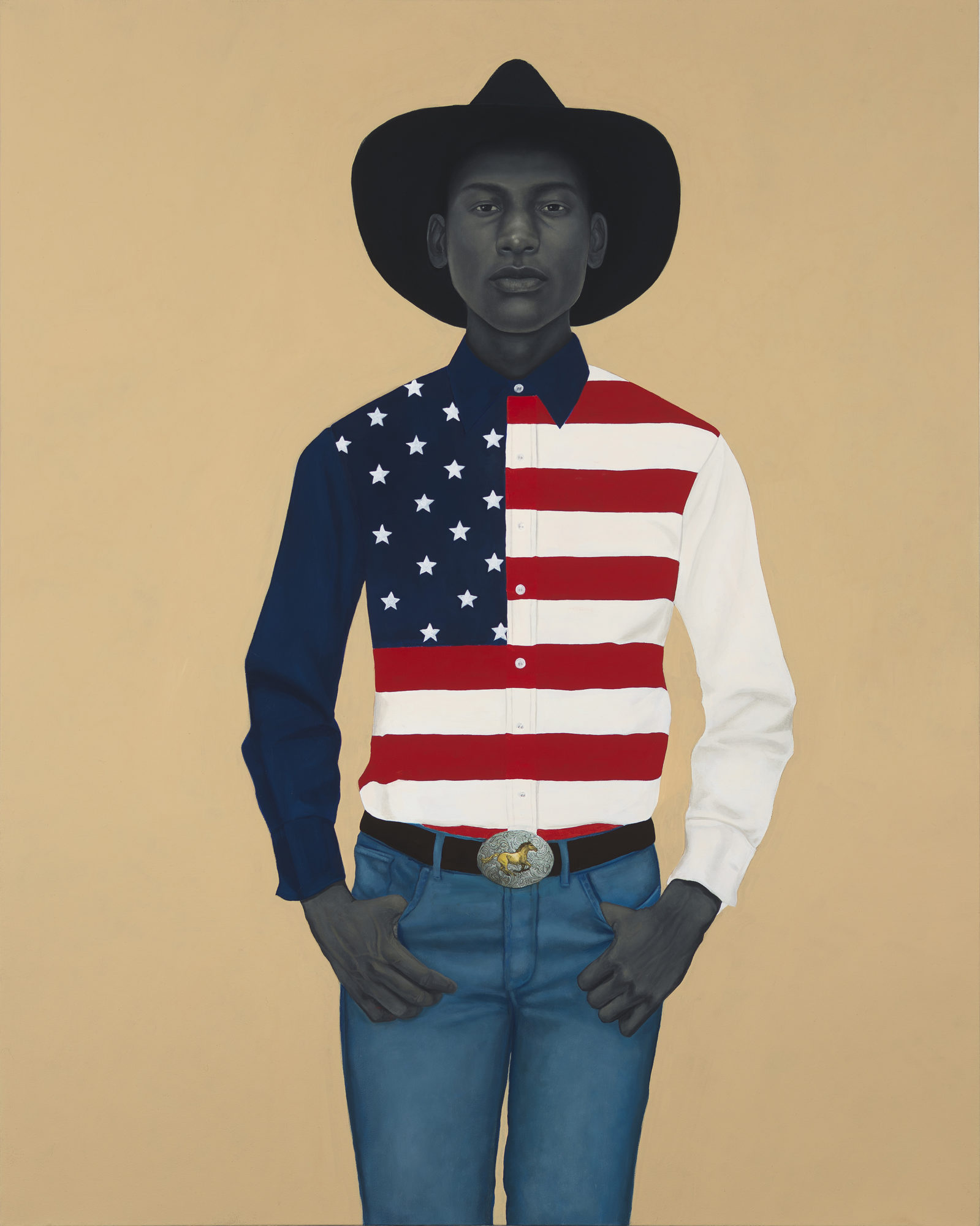

Amy Sherald, “What’s precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its presence (All American)”, 2017, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

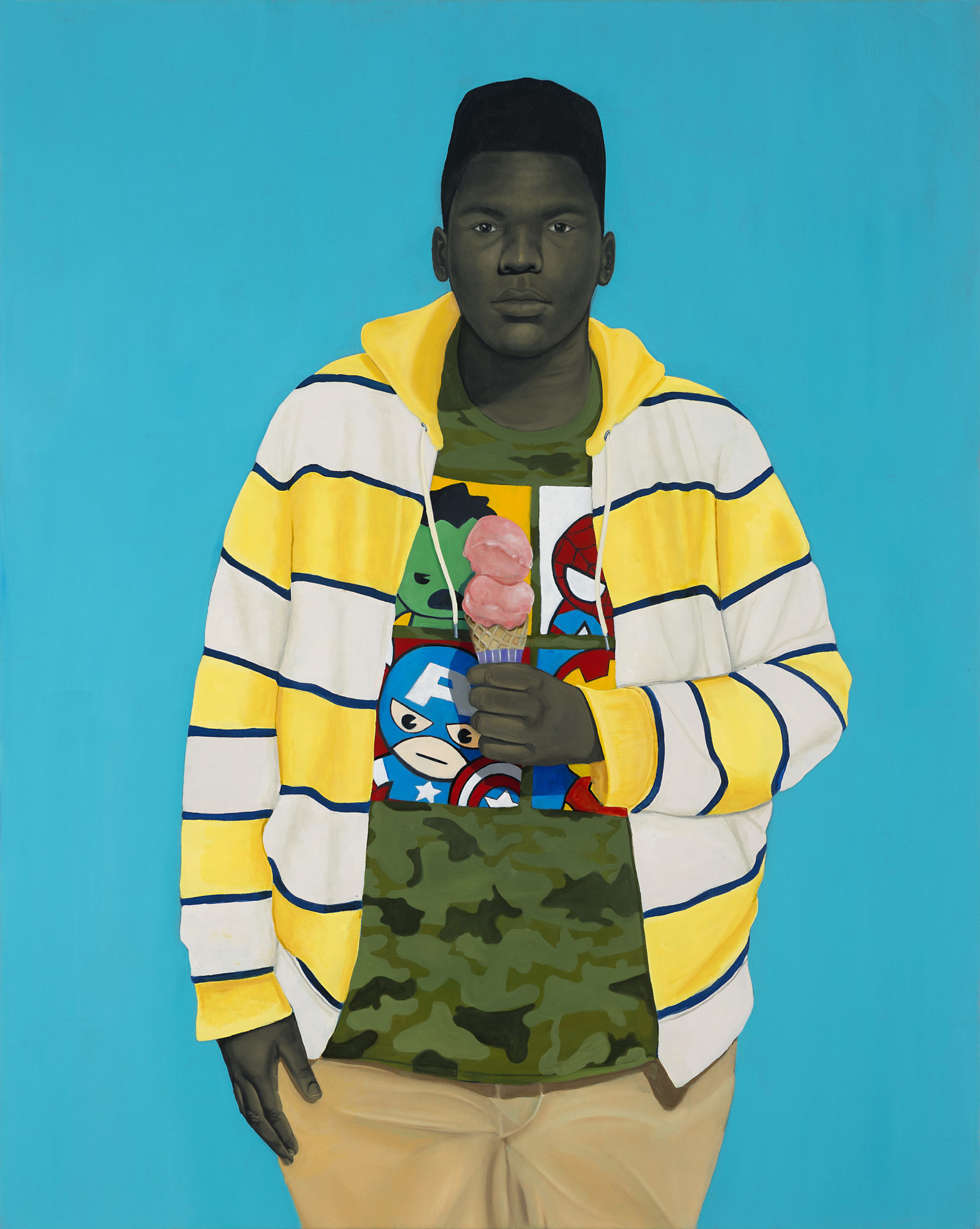

Amy Sherald, “Innocent You, Innocent Me”, 2016, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of artist and Hauser & Wirth]

VC: I think there’s a lot of romanticism around the artist that lingers today—sort of, as you say, like they work at whatever hours they’re inspired to work, or around whatever conditions they’re inspired to work in. For some reason I’ve always been sort of keen to bust that romantic idea open a little bit. Because it’s a damn job.

AS: It is.

VC: And yet what makes it, I think, uniquely challenging—and tell me if you agree—is that your purpose and your sense of self [are] really bound up in the work you’re doing.

AS: Your self-esteem. Now that I’ve been on interviews with people, and to the photo-shoots, people really think that this is something that it’s not, based off the questions that they ask. Because everybody needs a fairytale. But do we have fairytales about doctors? … You know, when you’re still in your becoming stages, it’s not easy. And it’s not pretty and it’s not cute, when you’re 30-something and you’re still being an Uber driver. It’s not easy to date when you’re trying to make something out of nothing—especially as a woman, you know?

VC: That’s a good distinction, too—because on top of that, there’s a certain kind of erotic capital that a guy has as the “starving artist” that a woman starting out doesn’t have.

AS: That’s what I’m saying—the 6 six o’clock shadow, looking disheveled … all that is not cute, I can’t. I don’t get to walk around with crazy-looking nails. It’s a lot different.

Amy Sherald, “They call me Redbone, but I’d rather be strawberry shortcake”, 2009, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

Amy Sherald, “listen, you a wonder. you a city of a woman. you got a geography of your own”, 2016, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

VC: So, what was the turning point for you, would you say? I assume it wasn’t the Michelle Obama commission that made it click?

AS: It definitely was.

VC: Maybe that’s another kind of fiction or fantasy of youth, right? When you’re sort of trying to make it as an artist or writer and you’re, like, “All I need is for one big thing to happen. I just need that one person in my industry to notice me, or I just need to go to this one event.” But of course, it’s a process. You mentioned graduate school earlier.

AS: That was at MICA [Maryland Institute College of Art]. That was a turning point. I mean, that was the beginning. I think, for people, the question is, “How did you make it happen?” There is no rhyme or reason. I kept working. I worked on my approach to the work that I wanted to make. I wasn’t very strategic—not in the way that I wanted to produce something to try to get famous. You have to pay attention to what’s happening in the world around you, what conversations are being had, and what kind of work is being given platforms in museums, and then you have to look at art history. But this is in hindsight. I’m not sure if you asked me 10 years ago, “What are you doing?” that I would say, “I’m really trying to figure out which way to enter the art world.” But there was something pushing me to look around and see who I was going to be if I was brought into that space and what I could see differently, while still being myself. So, naturally Amy is nonconfrontational, naturally Amy can let you know something or tell you off in a very diplomatic way (laughs). Back when I was thinking about what I was doing and going to New York and looking at shows—and I have never been sure how this sounds, I don’t think it sounds bad—I went to see Kara Walker’s exhibition, and I thought, “How am I supposed to process this within my contemporary life?”

VC: Can you say a bit more about that? A sense of obligation?

AS: Well, I mean, it’s very tragic—it still feels very tragic to me, it’s our past, and it’s right there to look at—all the nastiness, all the perversion. But then we walk out of those spaces, and we are us. I’m from Georgia, Kara Walker lived in Georgia, we have a commonality. But when I left that show, I felt like there had to be some resting place … on the opposite spectrum of that. I realized at that point what it was that I wanted to paint. I want to make images that are just us, being us, pictures of American life, black life.

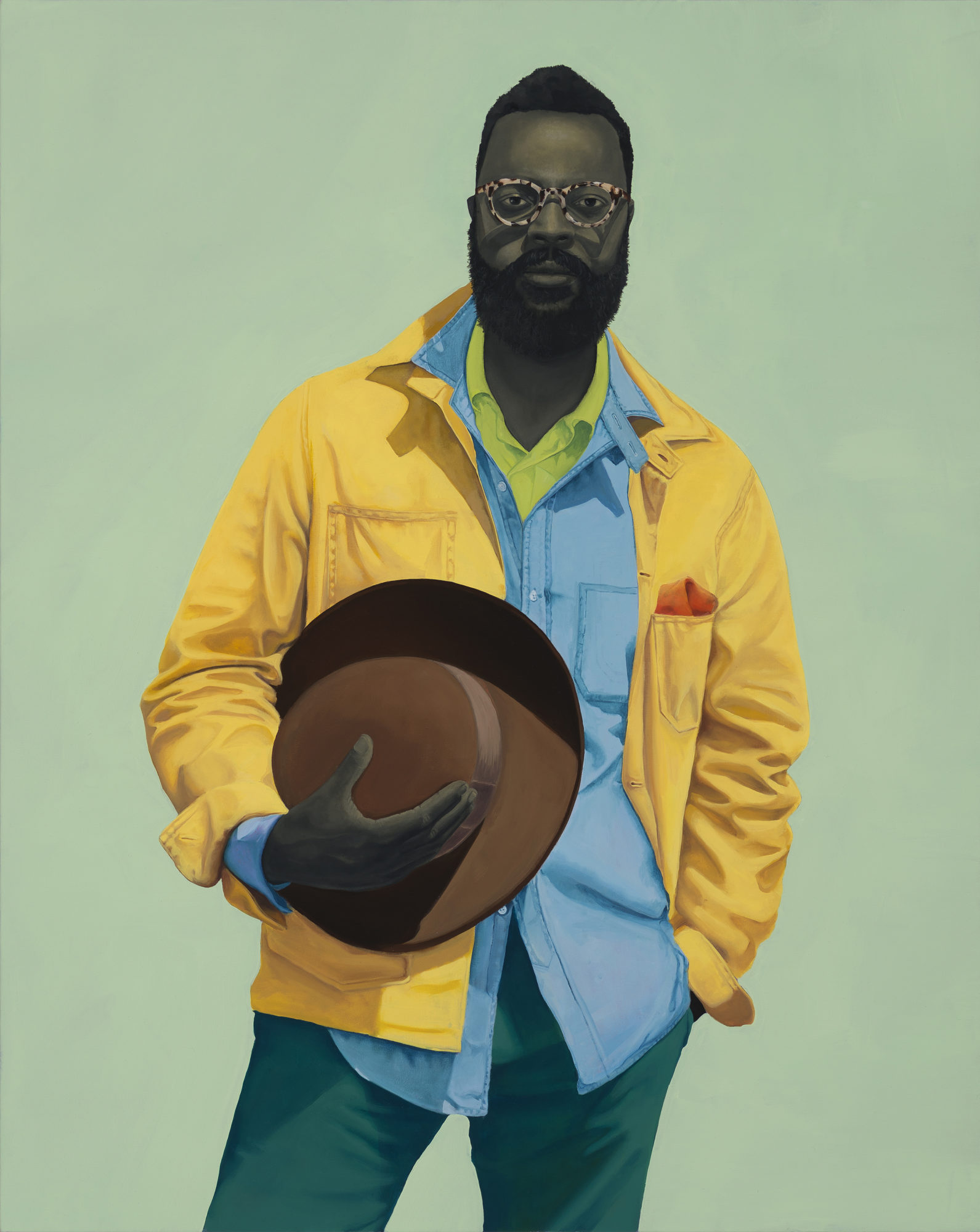

Amy Sherald, “All Things Bright and Beautiful”, 2016, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

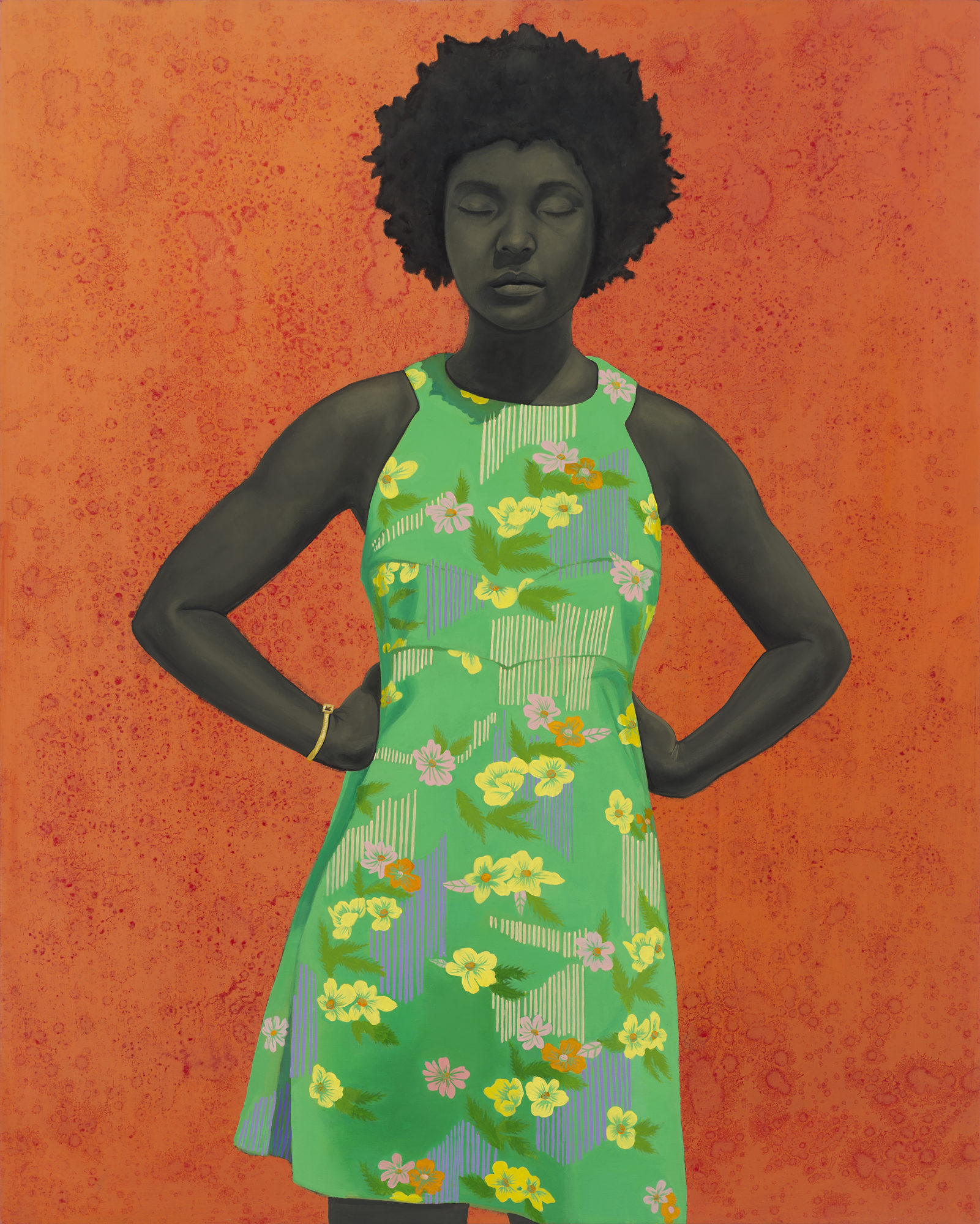

Amy Sherald, “Try on dreams until I find the one that fits me. They all fit me”, 2017, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

VC: This idea has come up in conversations and interviews in lately—artists are talking about breaking away somehow from predominant representations of black American experience that are purely orientated towards trauma.

AS: I felt that way in 2008— I was on a different journey, because I felt I wanted to get to know who I was outside all these external directives—all these things that kind of told me who I was.

VC: You mention your works being authentic to you, which is interesting because you’re known for your portraiture of others. What is the mechanism there, with your personal experience, your emotional or intellectual autobiography, being explored through images of other people?

AS: Well, in the beginning they were more about processing my upbringing, what I learned about myself after having moved back home for years to take care of my family, and being in Columbus, Georgia. My last memory there before I left to go to Clark Atlanta was of dancing with a white boy during my freshman year of college. One of his friends pulled him away and said, “You can’t dance with that nigger.” Come on, it’s 1992. I can’t disassociate the racism that I faced growing up with that place; I don’t have warm and fuzzy feelings about it. I know it has probably changed, but not in comparison to Atlanta, which has always been a blacker city and now even feels like Brooklyn in a way. It is still a stark contrast to what I am comfortable with, having travelled the world and experienced myself in different contexts.

VC: People talk about how much things have changed, but that sometimes feels insidious to me—like it’s a sign we’re glossing over some really systemic stuff that has to be radically undone, not just “improved.” I’m not from the South, but generally in America I find myself amazed at what people pat themselves on the back for. I keep having this conversation with graphic designers and artists about the visual culture of the South—like, what does the South look like, is it different from the rest of the country …

AS: I mean it’s really diverse—first you think of Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, then you think North Carolina should be a part of that, and then you extend it all the way over to Texas, and Texas is bordered with Mexico … and you get “Hola, y’all.” That’s part of our culture …. The Caribbean, too.

Amy Sherald, “Pythagore”, 2016, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of artist and Hauser & Wirth]

Amy Sherald, “Mother and Child”, 2016, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

VC: You mentioned traveling the world before and absorbing those experiences. To what extent would you say there is a kind of internationalism in your work, in the treatment of textiles or the color palette, for example?

AS: I’m not sure that there is a connection. I mean, not that the travels don’t find their way in—when people ask me about my palette, I usually attribute it to my time spent in Panama. And that might be a tangential connection, but when you’re a painter, and there are colors out there … it’s like having a box full of crayons. It seems like the logical thing to do, to use color, because it occurs. But my work is very American, in my opinion.

VC: Which makes it appropriate, I suppose, for the presidential commission. I have been speaking to artists working in various American cities outside … the New York/LA culture vector about their decisions to stay in places that aren’t really known for supporting people working in the arts. Baltimore has come up as one such city. What has been your experience working and living in Baltimore instead of, say, moving to New York, as many artists do?

AS: I don’t think I would be here talking to you if I had moved to New York. I think a lot of the opportunities that came my way came because I was in a smaller city. I used to try to go to New York for every single opening, thinking that’s how I was going to make more connections. There was this one time at an opening when I saw that they had this hidden door camouflaged within a wall that I saw someone walk into. That’s where all the people that I needed to be talking to were, but I’m just out here scouring the place for nobody, and I’m a nobody, too. It was a total waste of my time—if I don’t have any paintings that work for me, it doesn’t matter who I meet. Something clicked for me, and I stopped doing that, and I just started focusing on what I was making. Then, once I realized I had something to show, I was really careful about how I was going to present it to the world. An opportunity would come for me to exhibit, and I would turn it down because it wasn’t, you know—I always thought I was better than I actually was, I guess. But in Baltimore it just worked out that I was able to meet the right people here that I would have never met there. Say, if Hans Ulrich Obrist came to Baltimore, he would immediately think, oh, Amy Sherald lives here. That would never happen in New York City.

Amy Sherald, “fact was she knew more about them than she knew about herself, having never had the map to discover what she was like,” 2015, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

Amy Sherald, “Welfare Queen,” 2012, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

VC: Maybe there is also a weird reverse cultural cachet now, like people think it’s intriguing for a successful artist to live in “not New York”? Now that you’re on the radar of a really wide American public, how has your experience as an artist changed? Or your experience as a black female artist, specifically? And you aren’t just in front of the gallery scene; you’re in The New York Times.

AS: My experience? I feel like I am just starting to feel what that feels like. I think the power is that there are kids who, after seeing Michelle Obama’s portrait, are now interested in the arts. I went to an elementary school to surprise a group of kids, and you would’ve thought I was JAY-Z. And that’s very symbolic. I don’t play basketball, I’m not a rapper, and these kids were beside themselves. That’s the reason she chose me, I think—because it needed to connect to people. Like, this wasn’t about all those people who don’t want to see a black woman painted in gray. Nobody cares about them. We are trying to build a future for our children, and we need to talk their language and help them see themselves in a different way. So, it was powerful for me, once the New York Times article came out, because it’s being taught in art classes now, art teachers have access to images in schools where they are teaching mostly children of color who maybe don’t have to grow up like me, just looking at European paintings. They can see themselves. That’s the power. That’s the power of being mainstream. And as a black female painter, I think that power shift is just starting to happen, over the course of this year.

VC: Is that intimidating? In the sense that you’re, like, now what?

AS: I’ve been talking to Mark Bradford, whose work just sold at auction for the highest price ever paid [at the time] for a work by a living black artist. And what I’ve realized is that I need to ask for what I want. In college, I didn’t think about that.

Amy Sherald, “The Make Believer (Monet’s Garden”), 2016, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

Amy Sherald, “What’s different about Alice is that she has the most incisive way of telling the truth”, 2017, Oil on canvas, 54 x 43 inches [courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth]

VC: It sounds like your goals are personal, but also social or historical, in terms of a responsibility to make things more accessible, to make a contribution. It sounds like you have more to do.

AS: Yeah, I do.

VC: More to do, not just in the sense of your own goals, but in the sense that if a middle-aged white man makes a famous portrait, he’s not then suddenly in the position of contributing to the growth of a community.

AS: When you talk to black people, we always talk about our community and what we want to give back. You know, most people don’t have that kind of responsibility to their community, to bring up others wherever you’re going.

VC: Totally, it’s the opposite.

AS: Yeah, but it’s not a responsibility, it’s a pleasure to give and to need to give and in turn be given social leverage and power to make change. For me, all this is great, but what I feel like painting this portrait really did for me was give me power to create things—programming, or anything within a city like Baltimore that can allow other people to succeed. [To] me that’s the power of all of this, to create some change.