Amie Siegel: Provenance

The passages that populate Amie Siegel’s 2013 work Provenance [June 23, 2014—January 4, 2015] appear seamless and unhindered. Her expertly executed three-part installation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art consists of a central 40-minute video projection (Provenance), a framed spread from the printer’s proof of an auction catalogue (Christie’s, October 19, 2013), and a short video set in the auction room at Christie’s London, which documents the bidding battle for the title video, consigned by the artist to the Post-War and Contemporary Art Sale (it sold for $84,788). Within the installation’s frame, the viewer traverses disparate geographies, clashing chronologies, and competing object economies, yet the urgencies of the situation being documented are constantly neutralized by a perfected aesthetic of distance, detachment, and to some extent ambivalence. The high-definition video camera, a constant companion on the artist’s transcontinental reconnaissance mission, captures the pristine and seemingly uninhabited salons and living rooms of the Euro-American elite, then courses through auction rooms, photography studios, conservation facilities, warehouses, and cargo-ship holds, before exploring the contours, crevices, and cavernous chambers of Chandigarh’s modernist buildings, known across the world as achievements of that 20th-century architecture giant, Le Corbusier.

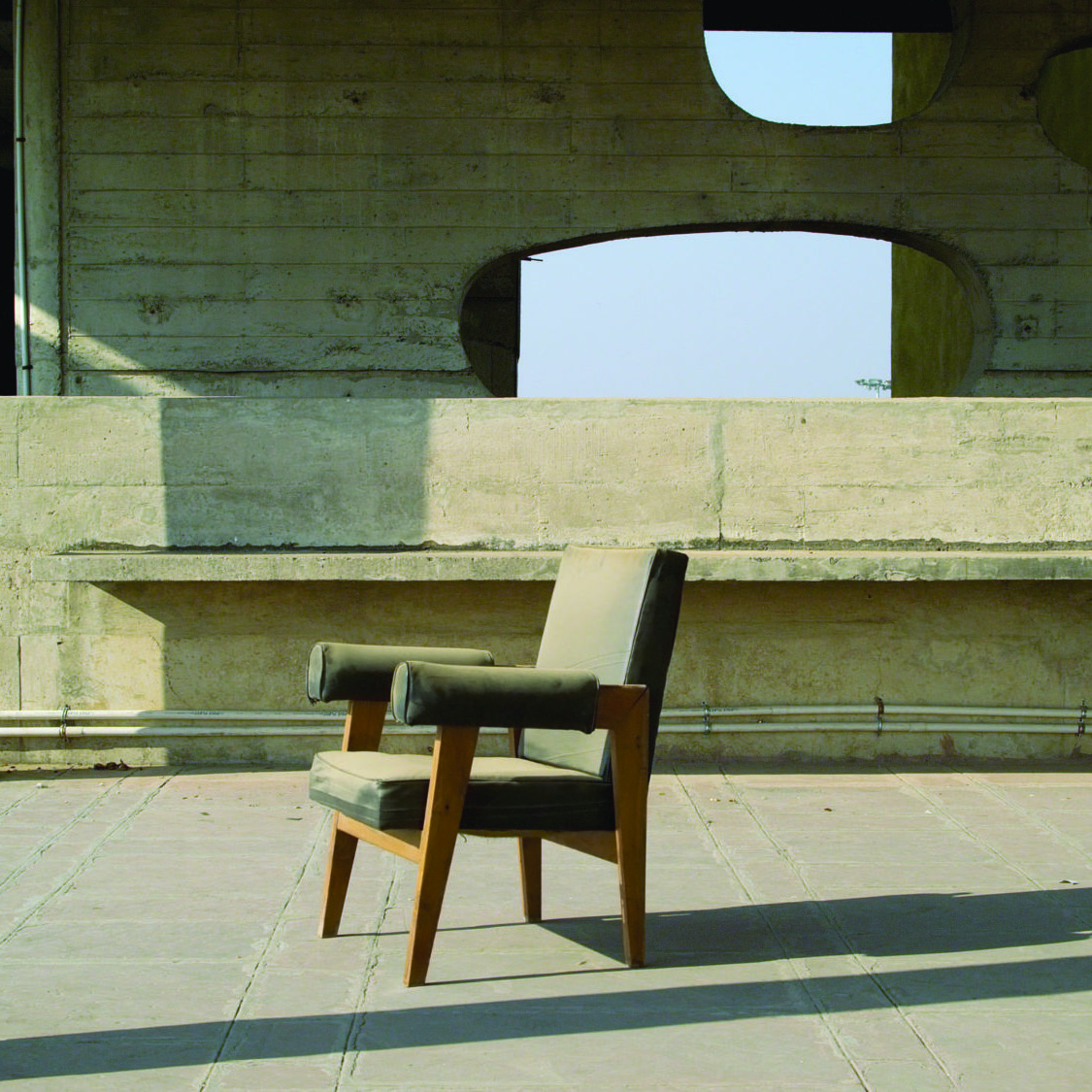

Amie Siegel, Provenance (still), 2013, HD video, color, sound, 40 min. and 30 sec. [courtesy of Simon Preston Gallery, New York]

The north-Indian city, planned and constructed from scratch in the 1950s and 60s to serve as a capital for the states of Punjab and Haryana, is the shared legacy of Corb (and company – Pierre Jeanneret, Jane Drew, and Maxwell Fry) and Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister. An avowed modernist, Nehru commissioned the city to affirm and embody his vision of a forward-looking, secular, and modern new nation, grappling with the trauma of Partition, the challenges of economic ruin, glaring rural-urban disparities, and a severe lack of infrastructure and industry. Every aspect of the new city echoed the ideals of the architects and their commissioner, from its key organizing principle (the indefatigable modernist grid) to the layout and design of its major public buildings (High Court, Legislative Assembly, Secretariat, Panjab University, and Government Museum and Art Gallery) and their furnishings. Desks, chairs, coffee tables, sofas, and cabinets were fabricated en masse, employing the designs of Corbusier’s cousin Pierre Jeanneret, his principal collaborator on Chandigarh, who remained in the city serving as its chief architect for much of his life. The unidentified yet easily discernible spaces that open Siegel’s video are impeccably appointed with carefully picked specimens from this prolific production. Chairs dominate this global survey of Jeanneret’s displaced furniture, running the gamut from the “Senate” variety with leather upholstery to the more modest classroom, conference room, and library chairs with cane seats and backs. In each of these spotless rooms, the camera pans and lingers on the individual design objects, doting on their economy of form and material while revealing subtle traces of their past lives and locations (painted inventory numbers remain visible on their freshly polished surfaces).

And thus the journey begins, a voyage-in-reverse, that is. Auctioneers accept bids running into thousands of dollars, in-house photographers scramble to make each furniture object appear unique and desirable, restorers work their magic on torn upholstery, broken legs, and damaged wicker. Shots of crowded warehouses and shipping containers lead us right back to the source – the provenance – of these mobile commodities. Siegel captures Chandigarh’s concrete edifices and their interiors exquisitely: the dull winter sun, the stray monkeys, the pools of water reflecting and softening the architecture’s hard edges, and indeed, the crowded offices where the same chairs and tables are subject to continuous use, wear, and tear. Over the years, hundreds have been condemned to rooftops and storage closets, where they await a purge under suitable protocols. Replacing them piece by piece are modular workstations and rotating office chairs, today enjoying the kind of universal proliferation that modernist design and architecture never did achieve. What is most striking is the coexistence of these period-specific solutions, heightened by the camera’s extended deliberation. No one seems concerned with stylistic incongruities or, more significantly, the depletion and slow pilferage of a unique legacy. Functionality, comfort, affordability, and ease of maintenance are the order of the day.

What, then, is Siegel trying to convey? Are we to be surprised that the all-subsuming art market continues to operate through the nefarious activities of dealers and suppliers who never fail to exploit weaknesses and leaks in the system? Or does she rehearse the trope of inherent asymmetry in concepts of heritage, cultural patrimony, and associated value, between modernism’s intellectual homeland and the peripheries where its productions have remained empty signifiers? The insertion of her own work into the auction house – wedged between Jasper Johns and Valie Export – speaks of the kind of self-reflexive strategy spawned by 80s institutional critique, whose potential, resting in the gesture’s immanence, may be altogether exhausted in 2014. For an incre-dibly sleek, seductive, and highly watchable work, Provenance doesn’t quite come clean about what is at stake.

Perhaps Corb’s anthropomorphic metaphors offer us something: if Chandigarh was designed with a head (the government and judicial headquarters), a heart (the central commercial district), and lungs (the network of green spaces running through), is the scavenging of its inner flesh and tissue symptomatic of a collapsed body, a lifeless organism? Looking beyond the images of dilapidation and decrepitude, we know the contemporary city endures, supported by its post-modern prostheses and an unshaken confidence in its ability to draw India’s one percent with the promise of wide roads, regulated traffic, and abundant greenery (Chandigarh consistently tops rankings of per capita income, living standards, and cleanliness levels in the country). The concentric logic of Siegel’s installation parallels the dialectic between postcolonial modernization and a home-grown modernism, set in motion by the formidable Nehru-Corb duo. This dialectic plays itself out repeatedly, its multiple syntheses continually reaffirming and servicing the demands of a global elite.