Alison Nguyen’s Andra8 and the Gig Workers of the Data Economy

Alison Nguyen, ANDRA8: my favorite software is being here, 2020-2021, HD video, color, sound, 19 minutes [courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NY]

Share:

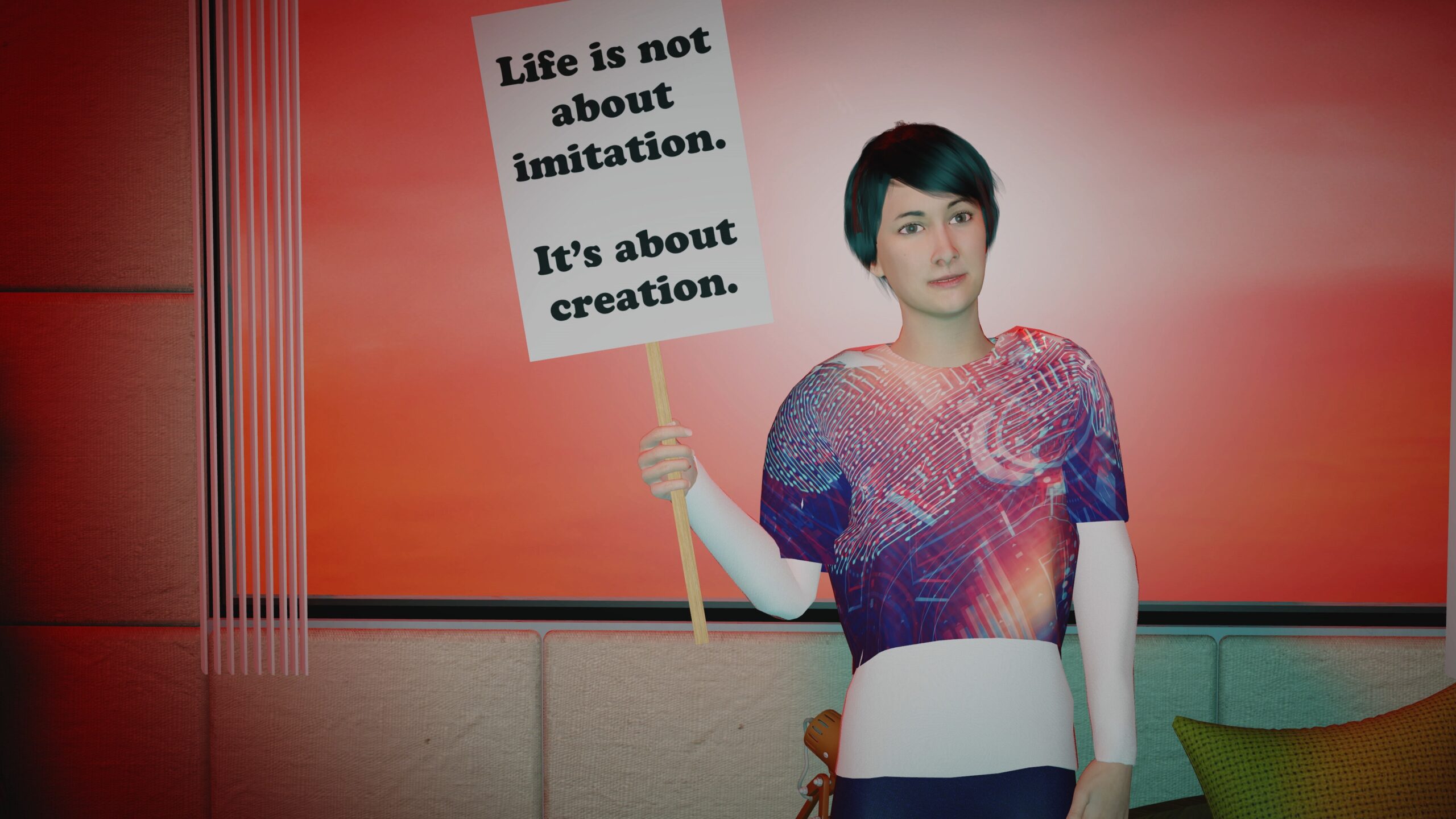

Sitting in front of a wrinkled sea-green backdrop is Andra8, the protagonist of Alison Nguyen’s 19-minute film my favorite software is being here (2020–2021). Andra8’s hair, swept to the side, is cut in a long pixie. Emblazoned on her crop top are the sprawling, layered traces of printed circuit boards, like ones so often conjured by the aesthetic imagination of cyber-futurisms. She introduces herself by monotonously listing her experience and skill sets, as if in a first-round Zoom interview following a barrage of rejection emails. She’s a “quick responder, fluent communicator in English, good with the tech, affordable and flexible, great at mental battles and cyber disconnect, cross-cultural platforms, [and] setting productivity goals.” She’s the so-called unicorn employee desired by many of today’s corporations that seek low-cost, high-yield worker output.

As she continues the tour of her curriculum vitae, the camera voyages into her working and living space. Strewn across the sunken, curved sectional she sits on—calling to mind the furniture’s analogy to the open, free-flow of collaboration that tech startups spew amid their core values—is the scattered material buildup of burnout and overwork: unused Post-it Notes, a capsized pen holder, opened and empty Chinese-food containers, keyboards, receipts, and storage filers. On a reclaimed wooden bookshelf sits an unevenly stacked collection of copy-pasted, vaguely titled coffee table books: Stone Architecture, Bauhause Isuee, Textiles for Us. Aimlessly placed midcentury-modern stools and chairs are crowded with yoga mats and dumbbells.

Alison Nguyen, ANDRA8: my favorite software is being here, 2020-2021, HD video, color, sound, 19 minutes [courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NY]

In 2016, Kyle Chayka coined the term AirSpace to label the sterile homogenization of interior decor. Described as the flattened aesthetic of coffee shops, bars, and office spaces, AirSpace is the result of a globalized visual lexicon that has leaked from the interiors of Airbnb apartments and homes. It’s the visually boring proliferation of subway-tiled kitchens and modular furniture, such that no matter where in the world you are, the space you inhabit never differs. If AirSpaces present themselves as anesthetized of any unique markings, then Andra8’s living quarters are an abandoned AirSpace that has renounced the upkeep of cleaning fees and public usage, and is replete with globular lighting fixtures and mimetic abstract art. It’s peak neoliberal interior design defined by market trends and consumer gadgets. But these accumulated objects of a life lived are purely ornamental, for Andra8 is the product of an algorithm.

Based upon—and voiced by—Nguyen, Andra8 consists of curated data. Her likeness is a software approximation, scraped and collaged from models on the dark web and AdobeStock images; her narrative is coproduced by the artist and an AI program created with researcher and programmer Achim Koh that feeds on B-list social media influencer posts.

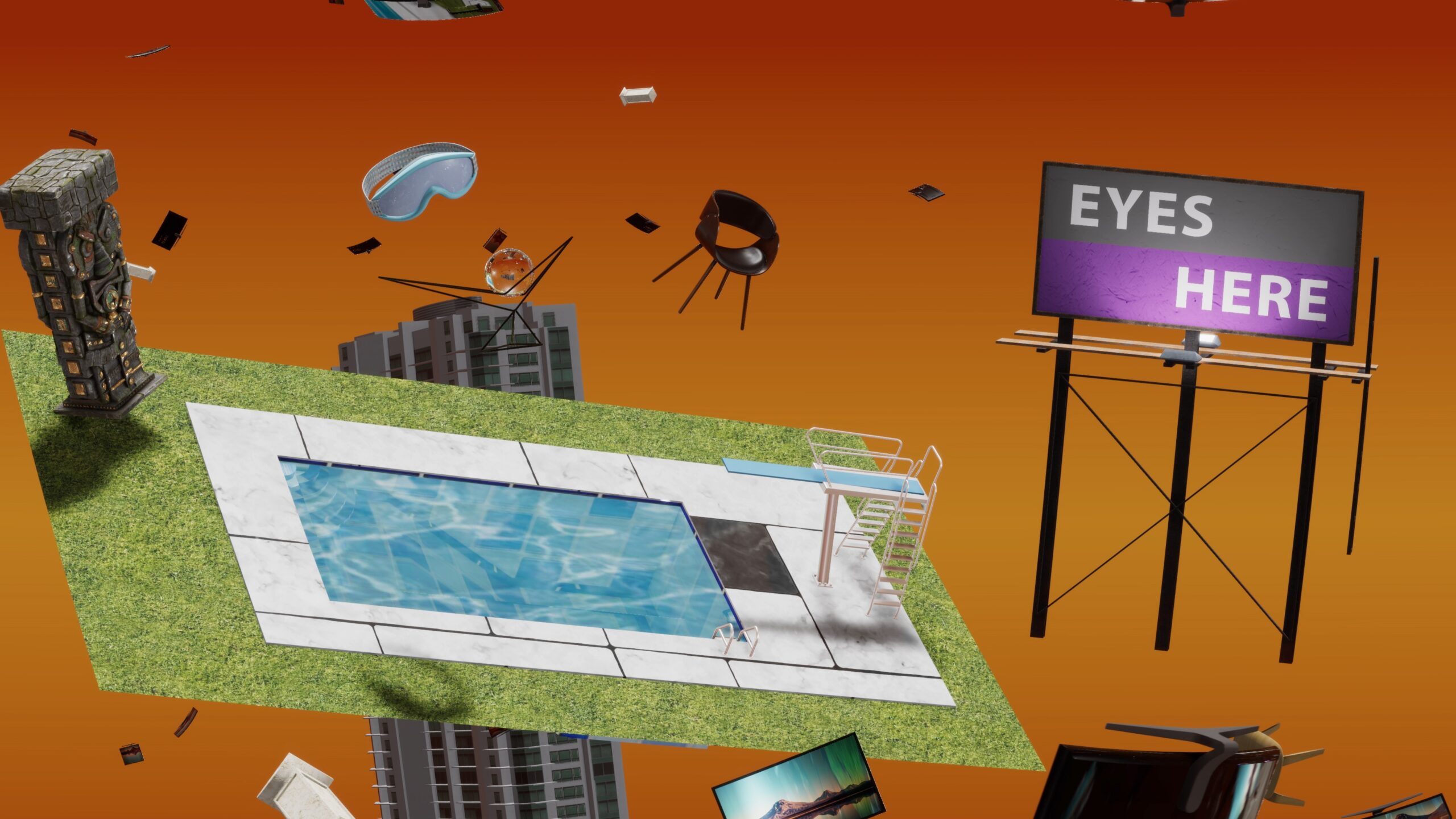

The domestic embellishments that distinguish her apartment are ready-made 3-D renderings uploaded by users on TurboSquid and Sketchfab. Marketed as a freemium service—a business model now ubiquitous in apps and services wherein additional functionality comes at a surcharge—she barters her labor for user data, consuming the latter in intermittent sips from her “data-shake” to survive. “What do you want to get back to doing?” she quips. She guarantees that the use of her skills allows employers to perform the life-affirming tasks—rooted in creative pursuit, not in routine—most often reserved for nepo babies, billionaire CEOs, and internet superstars.

Positioned as a digital factotum, she fills her day with the menial undertakings now common in the gig economy by providing her skills as a virtual assistant, ambient fitness guru, and influencer. In rote succession she awkwardly bops for dance challenges, arranges cupcakes for a content feature, and spasmodically paints minimal line art for a curated feed. She blogs, tracks followers, and cleans data. The language she uses is a mish-mash of the pseudo-aspirational “live, laugh, love” variety well-documented in the captions of budding tech, wellness, and lifestyle influencers who feign relatability through selective vulnerability and rhetorical questions. “What are you working on today? What do you want to achieve?” she asks throughout her day, desperate to extract the faintest trace of data in the form of tags, comments, shares, likes, and reposts. An apotheosis of abject contemporary upward mobility—stymied by rapidly rising costs, stagnant wages among the working class, discriminatory legislation, and precarious employment opportunities—she is a Sim in a world where cheat codes have disabled a diminishing needs bar, stuck in a hellish loop of uploads and downloads.

Alison Nguyen, ANDRA8: my favorite software is being here, 2020-2021, HD video, color, sound, 19 minutes [courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NY]

Alison Nguyen, ANDRA8: my favorite software is being here, 2020-2021, HD video, color, sound, 19 minutes [courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NY]

With her head resting on an enlarged, swollen bag of Classic Lay’s, she reflectively proclaims that “[she] can still have human rights even if [she is] a computer screen.” But absent protective labor laws, she performs her duties with exhaustive persistence, shifting from one task to the next with no bathroom breaks, meals, or PTO. She’s the AI embodiment of Big Tech’s dream employee, with no need to piss, no desire for professional fulfillment, and no family to go home to. Although Andra8 inadvertently proposes herself as a sinister solution for today’s omnipresent tech-corps to bypass workplace regulations, there already exists a close-enough alternative, found in countries in Latin America, Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Indeed, the outsourcing of numbing labor to populations considered disposable and worthy only of servitude has been, and will continue to be, a standard mode of operation among tech industries, irrespective of their company values. That many of these populations live in countries that are present or former colonies is no coincidence.

Alison Nguyen, ANDRA8: my favorite software is being here, 2020-2021, HD video, color, sound, 19 minutes [courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NY]

The global present is constituted by an existence that remains in the wake of colonialism’s destructive destabilization. Whereas historical colonialism sought to dominate and extract land, labor, and wealth through violent displacement and accumulation, its centuries-long buildup of refuse has shaped the ongoing history of global capitalism, entrenched asymmetrical power relations through systemic economic exploitation, and racialized hierarchies through infrastructural domination. Sovereignty has been achieved by many, but for postcolonial nations to be considered global players in the network of capital flow, they must offer their populations as a captive labor force working for poverty wages as a direct result of colonial practices. These very conditions are reflected by Andra8 and gig workers like her. Regarded as a dispensable citizenry, such workers sacrifice their own lifetimes for the social reproduction of the lifetimes of others. They labor as seafarers, nurses, live-in domestic workers, call center agents, caregivers, entertainers, and—likeAndra8—data cleaners. As Neferti X. M. Tadiar writes in her book Remaindered Life, they are a “transnational network of disposable and expendable populations from former and present colonies.”1

Andra8 masks this skewed relationship between disposable and valued populations. By advertising her services on Upwork and Fiverr—the latter of which grounds its practices in the very same sleepless work ethic Andra8 provides—she professes her allegiance to the global gig workers who hash together logos and slogans for $5 apiece. But she masquerades as disposable by association alone. AI systems like her—developed and funded by tech companies in the United States—are invaluable insofar as they may eventually eliminate the necessity of outsourced labor to people in disenfranchised countries, thus driving down the inevitable expenditures that are required of human employment. As evidenced by the tech industry’s recent hemorrhaging of jobs, a thriving workforce rarely benefits a company’s bottom line.

Andra8 emerges against a global backdrop articulated by the cleavage between the prized knowledge-producers in North America and Europe and serviceable surplus life in Latin America, Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. This technological fissure is a contemporary embodiment of a colonial practice that has morphed and adapted to an ecosystem propelled by cloud servers and oceanic fiber-optic cables. No longer does the colonizer need to traverse seas to establish political and monetary control, for today’s empires are determined through the ownership and monopolization of digital infrastructure and expertise. The disastrous effects of a disparate technological field have become searingly evident with the implementation of AI and machine learning systems.Heralded as the future of labor and poised to eliminate the minefield of misinformation thats ours the sociopolitical terrain, these computational systems have so far failed to operate as efficiently as tech companies have claimed. For people in the Philippines—a country whose digital topography has been usurped by Meta’s social networking and media service Facebook—this deployment has been fatal.

Alison Nguyen, ANDRA8: my favorite software is being here, 2020-2021, HD video, color, sound, 19 minutes [courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NY]

Facebook’s saturation of the archipelago blighted the country when Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte embarked upon his presidential campaign. Facebook’s machine learning algorithm, unable to distinguish fact from fiction, proved to be his most lethal weapon. Positioned as an advocate for a public that has endured an endless cycle of political corruption—initiated during the Spanish colonial era2)—Duterte campaigned on a promise to eliminate the rampant practices of bribery, nepotism, embezzlement, tax evasion, and fraud. During a notable campaign rally, Duterte declared to his constituency that he would dump the bodies of executed drug dealers “into Manila Bay, and fatten all the fish there.”3 His murderous call-to-action was posted on Facebook and thrust instantly into the viral sphere. There was no need to boost, no need to coerce, and no need to invest in paid ads—Facebook’s algorithmic amplification of engaging content was the only tool necessary to propel Duterte into the collective psyche. Pointed misinformation, agitative propaganda, and violent libel—in one instance, Senator Leila de Lima, a fiercely outspoken critic of Duterte’s war on drugs, became the victim of the rapid circulation of a doctored sex tape—soon multiplied like a virus on the platform. Duterte won through a campaign strategy of egregious abuse and vicious chauvinism. More than 7,000 people are estimated to have been killed because of Duterte’s drug war.4

The AI system deployed on Facebook (now Meta) news feeds purports to be a robust service capable of identifying and removing the exact forms of tainted data that empowered Duterte and his league of misinformants. It can cleanse one’s timeline of nudity, hate speech, violence, and terrorism, regardless of the novel methods humans use to portray such stuff. It can ensure democratic elections, a well-advised public, and a secure user experience. But for all its versatility and competence, like Andra8, this allegedly groundbreaking technology requires human input to function. These systems gorge on unremitting troughs of human-labeled, manually annotated, and repetitively flagged data through AI programs that instruct the systems to distinguish “right” from “wrong.”

Alison Nguyen, ANDRA8: my favorite software is being here, 2020-2021, HD video, color, sound, 19 minutes [courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program, Brooklyn, NY]

Behind the laborious task of analyzing this sea of data? Workers in Latin America, Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, many of whom are located in the Philippines, hired to examine hours of child pornography and violent beheadings for a meager wage, and unable to attain any psychological support required in this field of work.5 Andra8 is able to ceaselessly labor precisely because she is unburdened by the consequences of the corporeal. Meanwhile, workers in the archipelago are impelled to comply with irrational regulations and threatened with reduced salaries if labeling quotas are not reached. They are a captive labor force within the data economy that scrapes the shit and blood off the code which makes up our 24-hour consumption of digital media, while people in affluent countries enjoy a polished feed of shopping hauls, dinner recipes, and travel vlogs. Despite the enlistment of advanced AI moderating systems, people in the islands toil to ensure that the privileged digital experience remains unblemished by political deception and vulgarity, all while these laborers’ demands for a safer cyber experience are ignored. In 2022, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., son of the unforgivably corrupt and brutal dictator Ferdinand Marcos, assumed the Philippines’ presidential seat after a successful Facebook campaign that suppressed the multiple crimes of his father’s presidency

Back in Andra8’s virtual habitat, the protagonist grows weary of the grueling work she performs: drafting inspirational captions, hawking sponsored posts, and crafting emoji orders. She contemplates an existence unfueled by the human data that defines her, and in an act of frustrated agency, she launches her empty data-shake into the vast expanse of digital waste that lies at her dwelling’s periphery. Her skin starts to falter, displaying black craters of unrendered flesh, and her AI-generated speech becomes a nonsensical assortment of aspirational jargon, character attributes, and anti-work endorsements. “It takes a great deal of work to get the content you want to see on your feed, and I don’t want to work so hard,” she declares. She then exits the live-work space she has called her home.

Although recognized as an act of rebellion, Andra8’s refusal to participate in the data economy will have no effect outside the digital realm where she exists. The work she declines will undoubtedly be handed off to another AI program, inevitably forcing the further recruitment of people less fortunate, and ultimately burdening them with the tasks unfulfilled by algorithms and machine learning, while receiving none of the praise heaped on AI. Unwilling to endure the exhausting onslaught of digital labor, Andra8 represents the simple privilege of turning off. Yet most who work in exploited countries aren’t even given the option to log out.

Sasha Cordingley (she/they) is an arts and culture writer from Hong Kong and the Philippines. Their writing has been featured in Hyperallergic, C Magazine, and Dirt.

References

| ↑1 | Neferti X. M. Tadiar, Remaindered Life(Durham, NC:Duke University Press, 2022). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jon S. T. Quah,Curbing Corruption in Asian Countries:An Impossible Dream?(Bingley, UK: Emerald GroupPublishing, 2011 |

| ↑3 | Davey Alba, “How Duterte Used Facebook To Fuel The Philippine Drug War,” BuzzFeed News,September 4, 2018, online. |

| ↑4 | Job Manahan, “War on drugs: ABS-CBN research showsover 7,000 individuals killed in past 6 years,”ABS-CBN News, June 1, 2022, online. |

| ↑5 | Adrienne Williams, Milagros Miceli, Timnit Gebru, “The Exploited Labor Behind Artificial Intelligence,”Noēma, October 13, 2022, online. |