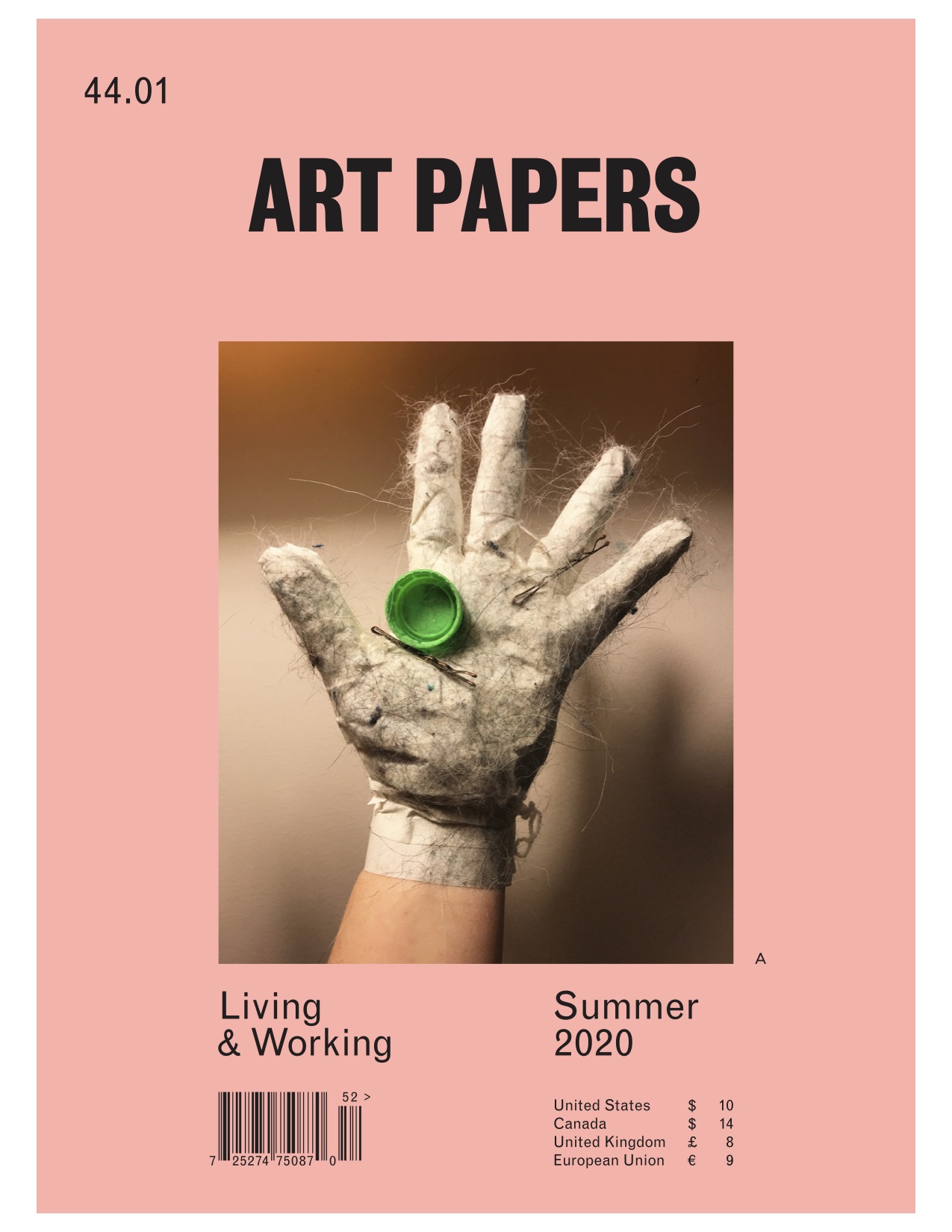

Alex Chitty: Things in Motion

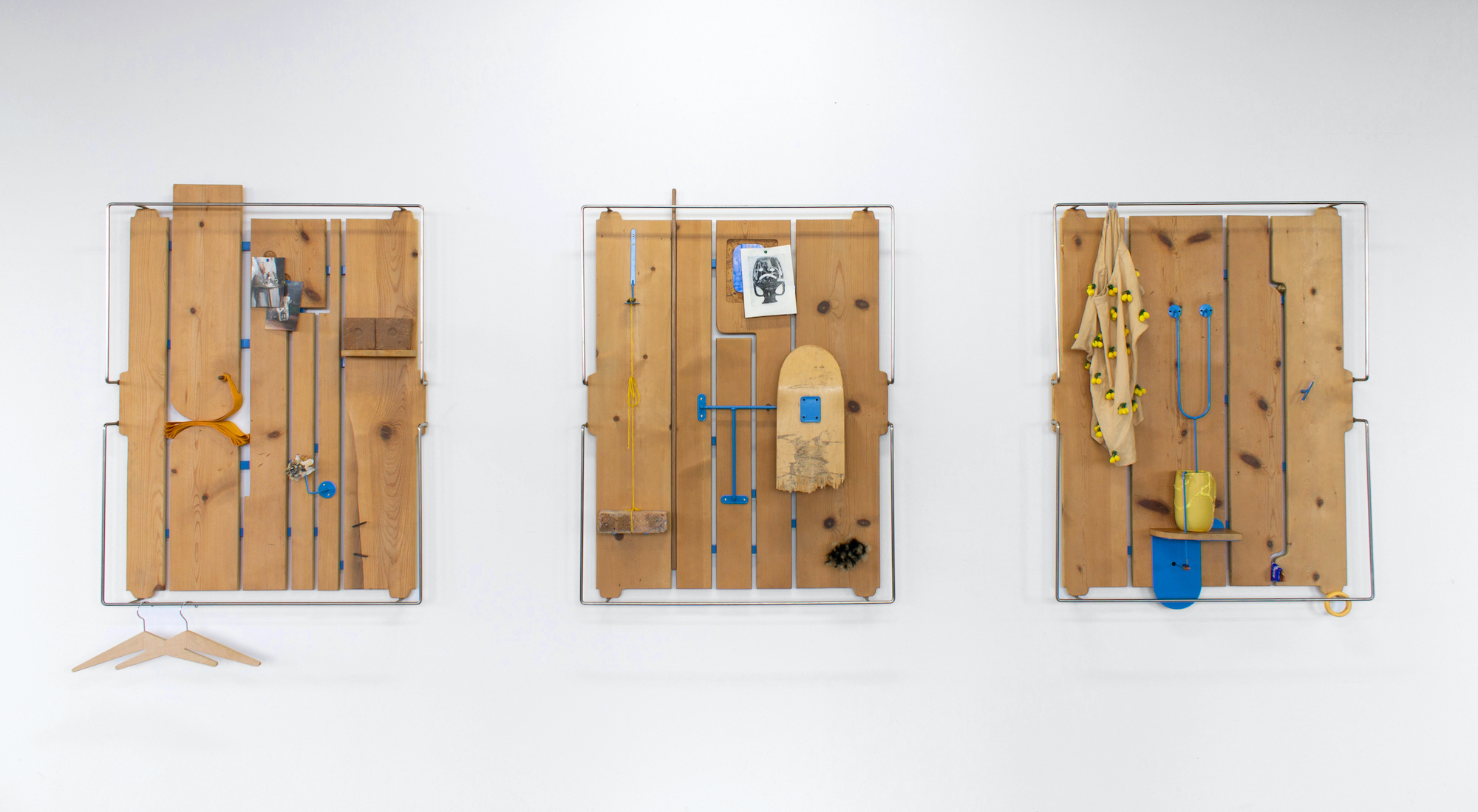

Alex Chitty, Siblings I, II, III, installation view, 2019 [photo: courtesy of the Artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago]

Share:

“One kind of looking allows you to simply see objects, useful human things, honest and concrete, which you know right away how to use and what for. And then there’s panoramic viewing, a more general view, thanks to which you notice links between objects, their network of reflections. Things cease to be things, the fact that they serve a purpose is insignificant, just a surface. Now they’re signs, indicating something that isn’t in the photographs, referring beyond the frames of the pictures. You have to really concentrate to be able to maintain that gaze, at its essence it’s a gift, grace.”

—Olga Tokarczuk, Flights

***

Chicago-based artist Alex Chitty’s practice cultivates this panoramic mode of engagement by offering sets of rough coordinates among which we might begin to situate ourselves in relation to the systems and structures around us. Originally trained as a biologist, Chitty is attuned to—but ultimately rejects—the ways we attempt to organize experience. Instead she produces sculptures, photographs, and installations that she describes as deliberately resistant to definition. In these works, she assembles open-ended constellations of objects and materials that are variously animated by our own associations, memories, affects, and positions.

Alex Chitty, Siblings I, installation view, 2019 [photo: courtesy of the Artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago]

Anna Searle Jones: As we speak, one of your most recent series of works, Siblings, is part of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art’s State of the Art 2020. I guess no one is looking at it right now, but it’s there! Like many of your sculptures, these three interrelated pieces bring together various kinds of material—a broken skateboard, bricks, photos, textiles—which you’ve altered and assembled in a way that sometimes confuses these categories. I’m thinking of something like the cast brass peach pit, for example. Can you talk about your relationships with these objects and the process of bringing them together?

Alex Chitty: I love the places in life and art where we look at something made of physical matter that actually exists in the world and begin to see or think about something other than what it is we are looking at. It’s strange because that act is the basic pillar of creative thinking or problem-solving, but it’s also stereotyped as a delusional or even potentially ignorant act. It’s at the root of any political, social, ecological, or personal change.

The Siblings pieces came out of thinking about where we expand or gather in order to grow, and where we reduce or carve away in order to grow. I had always thought it was the first: that you would grow by gathering. And then I met a stone carver, who carved marble headstones for graves, and he thought of it in completely the opposite way, carve away what we don’t need and we’re left with the crucial stuff. So, it’s the difference between excess and essence.

AC (cont.): I often am drawn to objects that are ambiguous in … their form, where they could be more than one thing—or that harness a kind of potential—and that are already referencing something from the natural world or something that’s designed by a human hand. The peach pit is great because it falls into both of those categories of excess and reduction. The meat is gone, the fuzzy fruit has been absorbed, and what remains is a thing that, in and of itself, is not alive but holds the potential for life, for the next thing. Casting any object in brass, for me, is not about altering its value, but more about shifting a viewer’s understanding of time. It is a depiction of itself in the same way that a photograph represents a thing without the thing actually being present.

ASJ: I showed an image of one of the Siblings works to my six-year-old daughter, and her response was, “Is this a machine?” I thought that was really interesting that she picked up something of the systematic nature of your work, the dynamic interplay among all the different elements, and the role of the viewer in “turning it on,” so to speak.

AC: I love that description of it as a machine or [its] potential to be a machine.

The whole is made up of a lot of parts, and sometimes to understand the parts you have to look at the whole. I think about a lot of my works as mind gyms, a place where viewers can go to build muscles, in terms of a way of looking or being, or recognizing oneself looking or being. I think about the viewer a lot. When I draw out my wall pieces, I often draw from the back, as if I’m the wall looking through the work towards the viewer. It lets me kind of embody the piece and imagine how I, as the piece, can be looked at. It helps me edit what needs to be there and what doesn’t.

My partner is a machinist, and I’ve been thinking about jigs for a long time, because when you make things you often have to make this other thing that helps you then make the moves you need to make on the saw. I think of the work as a jig. It’s a thing in and of itself that has a very specific function and will help something else happen.

ASJ: You’ve described your work before as algorithmic, which makes a lot of sense to me.

AC: Totally. It has a step-by-step process that can be listed, but it doesn’t have a result that can be named ahead of time. So, it’s a lot like science experiments in that way, where you kind of have an idea, but you don’t really know.

Alex Chitty, Siblings llI, installation view, 2019 [courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago]

ASJ: I’ve been reading Olga Tokarczuk’s novel Flights, and there’s so much in it that resonates with your practice for me in terms of a certain nimbleness and range of forms and perspectives. I feel like you share some sort of sensibility. Are you familiar with the book?

AC: I just finished it. Reading that was, for me, like reading a nonfiction book in terms of the things it made me think about. The objects that I use are fragments pulled from somewhere, which means they’re carrying this history and this narrative, and then they’re put into a new place as a fragment and part of something larger.

There’s a quote right at the beginning that I keep reading over and over again: “Standing there on the embankment, staring into the current, I realized that—in spite of all the risks involved—a thing in motion will always be better than a thing at rest; that change will always be a nobler thing than permanence; that that which is static will degenerate and decay, turn to ash, while that which is in motion is able to last for all eternity.”

That’s something I think about a great deal in my work, especially when I have to try to talk about it. For me the poignancy wasn’t in the individual narratives and what those small stories were about, but [instead was in] this overall feeling that I was left with that is completely unquantifiable. There is no way to describe it in words, because she talked about everything around it. This is also the idea that I have been thinking about since Trump got elected and trying to have happen in my work, which is multiple perspectives existing in one moment.

ASJ: You’ve talked in the past about the appeal of a vision that runs “in contrast to the ‘realities’ we have either inherited or built for ourselves.” Your work is also quite resonant in the way that it taps into conventions and histories of interior and industrial design, architecture, commercial display. It has a distinctive aesthetic allure that we recognize from these fields. How do you think about deploying elements of those fields’ visual language, while at the same time pushing back against the way that their practices often fuel a drive towards standardization and commodification?

AC: I rely on objects in the world that are so recognizable that we hardly notice ourselves seeing them anymore. They pull you in because you think you recognize them right away, but once you’re in there I’ll often tweak them somewhat, so that what you thought was familiar has a glitch to it and you have to look a little bit closer. It slows you down—it’s a speed bump.

I think design is a field that was co-opted by commercialism. When you look at the core root of designing an object, it comes from a desire to make the world a little bit better, whether that’s efficient or less expensive or [feels] better. I came across a student who proposed a project [about which] I was, like, “There’s no way this can ever be; it’s insane.” So I ended up researching speculative design, which is when you design for a world that doesn’t exist, and I realized that’s exactly what I do. That’s exactly what so many artists do. And when you design for a world that’s different from the one you’re in, it sets up a really clear path between where you are and what changes need to happen in order for you to get to a place that you can imagine existing.

Alex Chitty, the sun-drenched neutral that goes with everything (unit 5), powder coated steel, blackened steel, glass, oak, ceramics, 77″ x 34″ x 12”, 2015-2016 [photo: courtesy of the Artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago]

ASJ: One thing I think about when I look at your work is value. It sounds like you’re saying that you estrange the objects from their original, ostensible value, and this opens up all these other worlds of possibility for making meaning and measuring worth.

AC: I have gotten questions about why I use valuable materials in my work. It’s funny—they’re not actually valuable materials in terms of exchange, but I finish them or treat them or sand them or place them or hold them in a way that denotes a kind of care. Sometimes the wood has been touched all over in order to have a polish. I think [the fact] that objects retain that history, and that value, comes through in those ways. The value lies in the narrative, and within the works I tend to create a narrative by the way that I hold the object, whether it’s affixing it in place or casually hanging it in a way that’s temporary, or by the way that I hold it in relation to something else.

I have, in one of the Siblings pieces, this rolled-up, empty chip bag. I really love food where its shape and content, which is potato chips, has nothing to do with the flavor you end up thinking about, which is buffalo chicken, while you’re eating it. I like that discrepancy between the skin and the core of something, and so I rolled it up and shoved it in between the two planks. And then I got an email from the museum that said that someone had removed it and they were horrified and how could we replace it? And it just involved eating another bag of chips and shoving it in there. [both laugh] But I love that it went missing because it was exactly that—it was someone else’s understanding of the value of a chip bag and thinking, perhaps, that someone had shoved it into my work and thereby lessened the value of the whole piece. For me, the value of that chip bag was its weird blue color with the yellow writing and the fact that it had this reference to content versus surface.

ASJ: Your recent project here in Chicago at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder, is indicative of the way that you think about systems and influences and perception. You made an intervention into their presentation of work by Alexander Calder. How did that come about, and what was it like to work with another artist’s output as material?

Alex Chitty, Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder, installation view, 2019-2020 [photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago; courtesy of MCA Chicago]

AC: Working with actual Calders was such a challenge and so much fun. When you see them up close, and you get to measure them and see all their personality traits, you can recognize in them the kind of pleasure that I think a lot of artists take in the making of objects, the thinking about what an object would be.

It came about because I’ve lived in Chicago for about 15 years, and the MCA always has Calders. I didn’t know why a contemporary art museum would always have a Calder show up, so I was curious. It turns out another friend of mine, Raven Falquez Munsell, an independent curator, also was curious. At first it started as kind of a joke: she wanted to write a review of every single Calder show that the MCA had ever had as a single review. And I wanted, if I ever got the opportunity to have a show at the MCA, to instead just make a big, fake Calder and put a fuck-ton of industrial fans on it, so it would dance and never stop.

How that became an actual show—it began by us posing a bunch of questions to the museum about what constitutes a Calder being on view, because it’s part of a promise loan that stipulates that it has to be on view for 40 years. As I learned more about that, it became less of a joke and more of a serious matter for me and Raven, in terms of what patrons mean and how deeply it can influence what a museum is allowed to say, and then what artists are allowed to say.

Alex Chitty, Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder, installation view, 2019-2020 [photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago; courtesy of MCA Chicago]

ASJ: What was it like working within the institution of the museum? Had you worked in a museum of that scale before? [Calder’s body of work] is, in itself, an institution.

AC: I find limitation pretty generative, because it’s a system, and you can recognize it and then sidestep it. The title, Becoming the Breeze, ended up being not just the title but also a mode of functioning within the restrictions and constraints of both an actual Calder and the MCA. You can’t be rigid about something, you just have to become liquid and move around it and keep your eye on your goal, so that you end up somewhere near there. The way the show looked was nowhere near how I imagined it when I first started thinking about it, but for me the way that it functioned was right on point.

ASJ: Speaking of adaptation, we’re in a weird time right now. What does a good day look like for you at the moment?

AC: I honestly don’t know that it’s been a good day until I’m about to fall asleep and I’m, like, “Huh. I did it. We did it! That was a good day.” It’s been a very strange time because of the presence of these dual realities. I got handed a gift [of being] in my studio, something I’ve always wanted, which was just time and the feeling that when I’m in there I don’t have to be anywhere else, there’s nothing else I should be doing. Nobody’s watching what I’m making, and so I’m just making to see what something will look like. And that’s such a gift, to be able to roll so slow. But it’s coded in a lot of sadness and a lot of grief and fears about an unknown future. So, a good day is when I can toggle between keeping solid track of this larger picture that’s going on and then letting myself forget about that for a moment to find the places in life that make it good. That’s a good day: if I can do both of those, on and off, and not too much of one or the other.

Alex Chitty, Bunch of Pussies (Stacked), 2020, sheet metal, paint, and steel wire [photo: courtesy of the Artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago]

Alex Chitty, Bunch of Pussies (Swarm), 2020, sheet metal, paint, and steel wire [photo: courtesy of the Artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago]

ASJ: In the spirit of being open to how things could be, as an artist and as an educator, too, as we come through all of this, what would you like to see change in the art world, and what do you feel like you want to work to preserve?

AC: I’m a pattern-seeker, so I’m really quick at looking at where everything is the same and where it’s broken and how it could be a hell of a lot better. I think that probably comes out of the biology side. All right, to list it: art school should not be as expensive as it is. There’s so much value in art school, but a lot of the cost of it is unexplainable. We pay $5,000 to learn screen printing or digital photography, when those are skills that I could learn on my own from the Internet, or by getting a book, or talking to someone [who] does it, or going to a workshop. It’s more about learning how to learn, and then working really hard and finding the people [who] know what you want to know and helping out to see how the system runs. Teachers could be paid more. There shouldn’t be 75% of staff being all adjunct faculty and not having health insurance and not having benefits and not being able to have any savings, so they can’t afford to move or leave or have kids or buy a house or pursue a practice. I think that art education prepares students for a world that doesn’t actually exist. Whether you’re going into teaching or you want to be an artist, that world in America doesn’t actually exist for you. And there’s a way … we could structure education that takes that into account. It could be a lot more creative.

So, what would I preserve? The community in Chicago is why I’m here, it’s why I love this place. It’s given me a real sense of belonging, and it’s taught me so much, and it’s been wonderful to watch other people here. The pace, I would keep, the pace that we have right now. Art takes a lot of time; it should take a lot of time, and the pace that we’ve established for the production of art and the consumption of art doesn’t really align with the potential qualities that it holds. And in relation to a lot of the projects that I’ve done, too, there’s time now for little things to have great impact. Conceptually, politically, emotionally, I align with that aspect of the present moment.

***

This interview originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.