Coleman Collins, The Upper Room

Coleman Collins, The Upper Room, 2025 [courtesy of the artist and Brief Histories, NY]

Share:

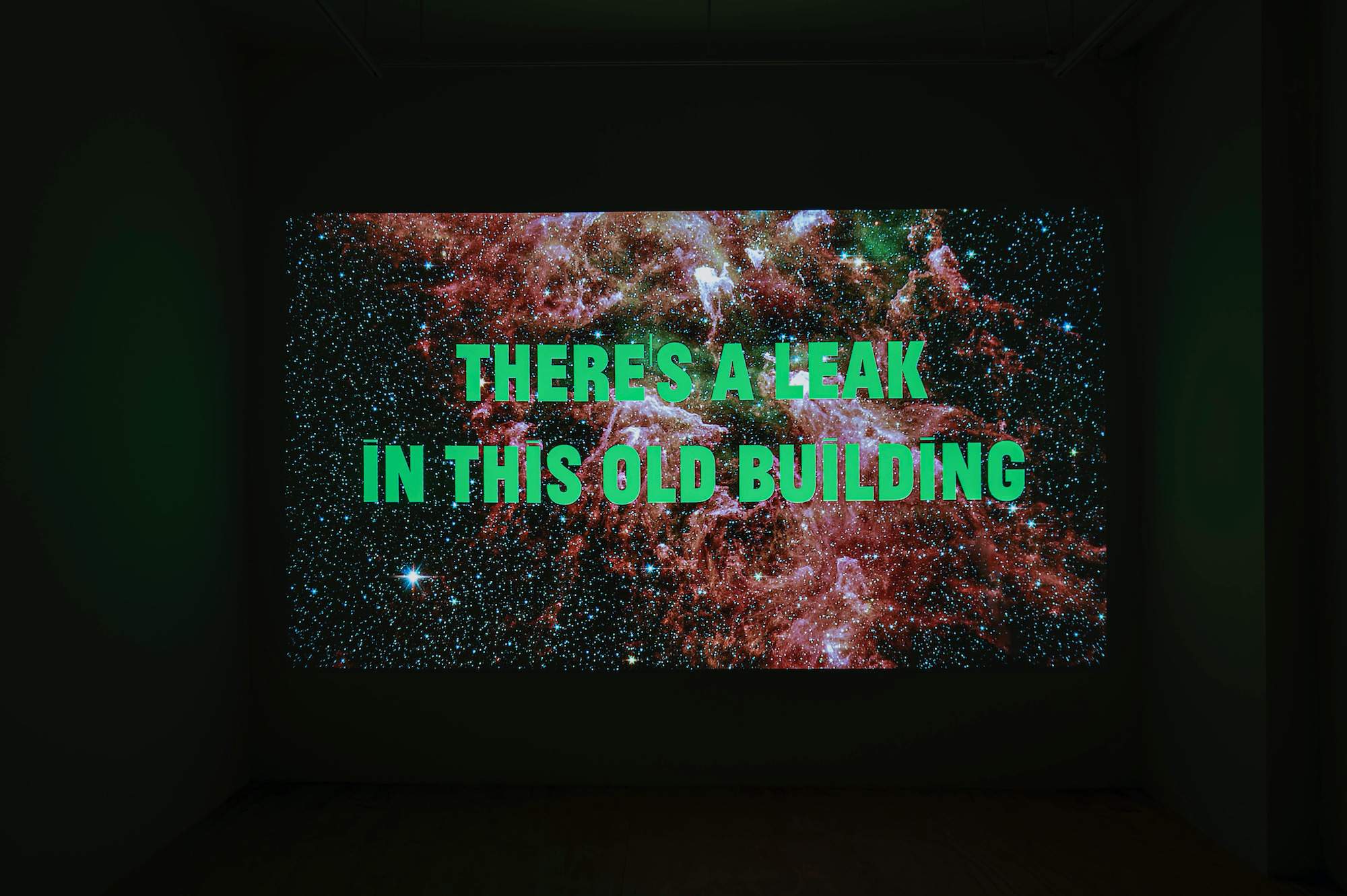

Exiting the elevator to Brief Histories, located on the second floor of an inconspicuous building in New York’s Chinatown, I hear gospel music. “There’s a leak in this old building, and my soul has got to move” croons a voice, slowed and reverbed. It belongs to Coleman Collins’ most recent video work, The upper room (2025), which probes the possibilities of Black liberation—from a country, a world, a past, and a present.

Coleman Collins, The Upper Room, 2025, UHD Video, 16:9, stereo sound, 20 min. [courtesy of the artist and Brief Histories, NY]

Coleman Collins, The Upper Room, 2025, UHD Video, 16:9, stereo sound, 20 min. [courtesy of the artist and Brief Histories, NY]

Throughout the work’s 20 minutes, an unseen and unnamed narrator details their search for escape, the specifics for which are enumerated by Garvey—a Black man with salt-and-pepper dreads who resides in an empty, stark-white apartment uptown, on 116th Street. Garvey sets the precedent. He tells tales of exodus that are, in sum, nonstarters (moving to Canada, where frigid temperatures are anti-Black, he states), unfinished (a Space Is the Place cosmic expedition, the first of two serious attempts at escape), and admonitory (repatriation via settler colonialism, the second). Each serves as a chapter in the film and is paired with a succession of still imagery that visualizes the recounted chronicles in the manner of a low-budget documentary.

It’s no coincidence that Collins produced this work as a still-image film. The no-frills form makes its content easy to digest. But a closer look at the imagery reveals that something here is not quite right. I recall the torrent of articles advising, with urgency, how to identify material produced by AI: Is there inconsistent texture? What about light and depth? Are the details polished and glossy? Collins doesn’t make it easy. The video has no pope in an oversized Balenciaga jacket or Instagram-perfect six-fingered partygoers. Rather, the images the artist employs encompass the mundane, the historical record, and the categorically credible. There are depictions of a community bake sale that contain undefined, irregular pastries smothered in cream; Black astronauts wearing flight suits and sitting motionless in a space shuttle, eyes turned to the sky; plantation-style homes that run the gamut of decay; and various other photographs of people in conversation on sofas, in combat, or staged for portraits. Some of these individuals are real. Among them are Nina Simone, Emmett J. Scott, and Bill Robinson. Others contain no trace of the living except, perhaps, in their name, as is the case for Garvey, conceivably named for Marcus Garvey, the Pan-African “Back-to-Africa” organizer and activist whose ideology is woven into Collins’ manufactured narrative, making its initial appearance in the first serious attempt at escape: The Pan-African Cosmic Expedition.

Coleman Collins, The Upper Room, 2025, UHD Video, 16:9, stereo sound, 20 min. [courtesy of the artist and Brief Histories, NY]

The voyage, Garvey tells us, lasted three months, with the intention of transporting an all-Black crew to an unnamed exoplanet. Transmissions ceased eventually, the location of the shuttle unknown. Some believe they made it to their destination, others that they crashed. I remember Martine Syms’ The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto, which offers an alternative to Black worldbuilding in other worlds by staking its claim in a Black humanity that is fully invested in the present. “Out of five hundred thirty-four space travelers, fourteen have been black. An all-black crew is unlikely” it states. Here, Syms is right. No part of The Pan-African Cosmic Expedition is bona fide except for its allusion to/continuation of a legacy of Afrofuturism that has envisioned space as a final destination for Black futures.

The second attempt at escape, The Republic of L—, is a colony on the West coast of Africa for freeborn African Americans and the emancipated, which was “founded for and by the colored people of the world.” The Republic of L—, Garvey says, was intended to be a haven for the newly arrived settlers, a refuge from the oppression, discrimination, and inhumanity experienced by African Americans in the United States. For many Black folks, Garvey continues, this atavistic journey across the Atlantic was a welcome endeavor at actual freedom. Their time there, however, was defined by their own inability to think beyond Western capitalism and colonization: they displaced native tribes, razed forests to build farmland and grow cash crops, and built mansions which mirrored those of the Antebellum era. I was engrossed and swiftly pulled out my phone to learn more. But this search proved the artist’s deft ability to collapse the real and the imagined, a challenge in veracity, compelling viewers to embark on their own fact-finding expedition through the film’s archival easter eggs: fragments of archival documents, anthropological portraits, and war photography. The Republic of L— does not exist. Its history, however, does.

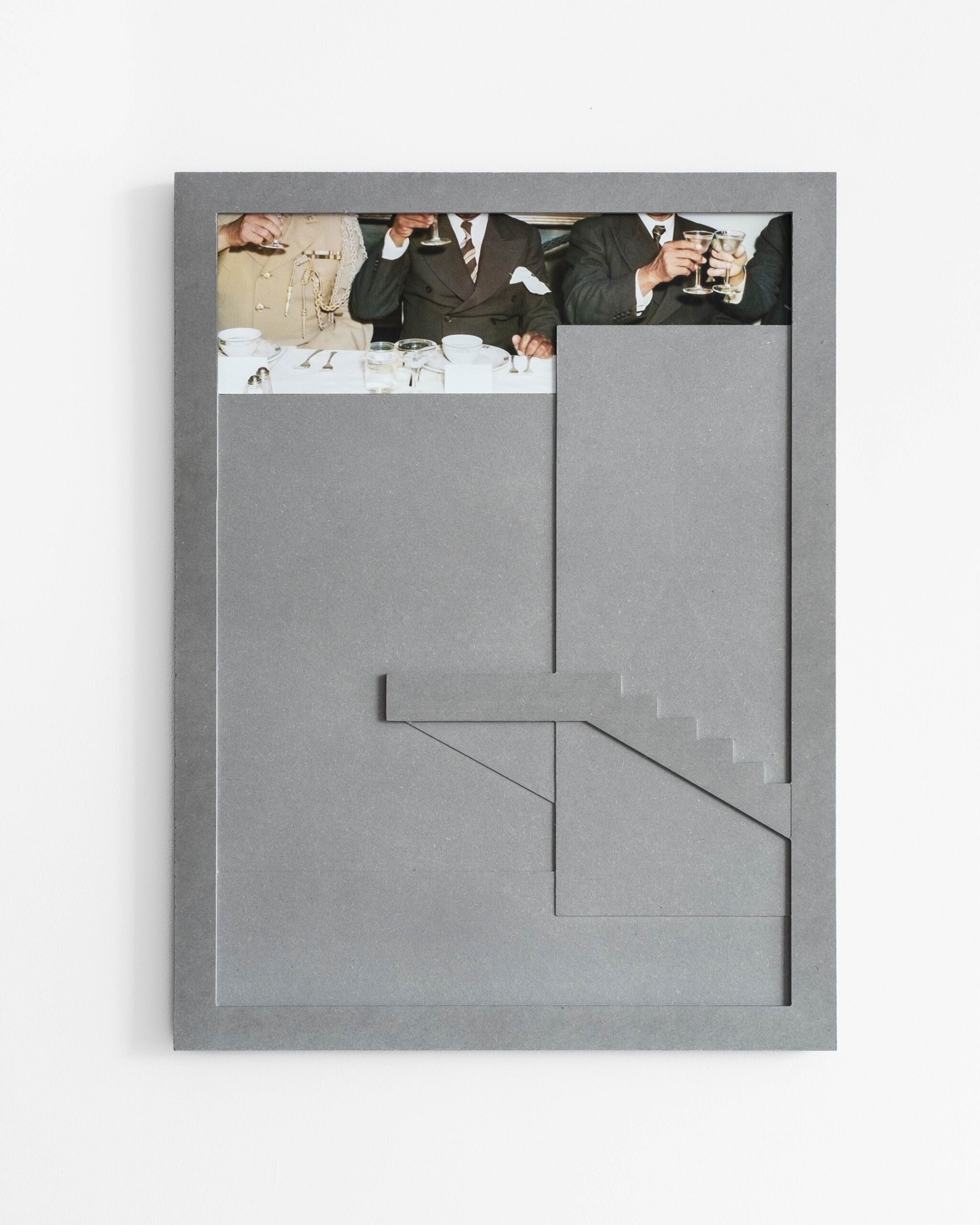

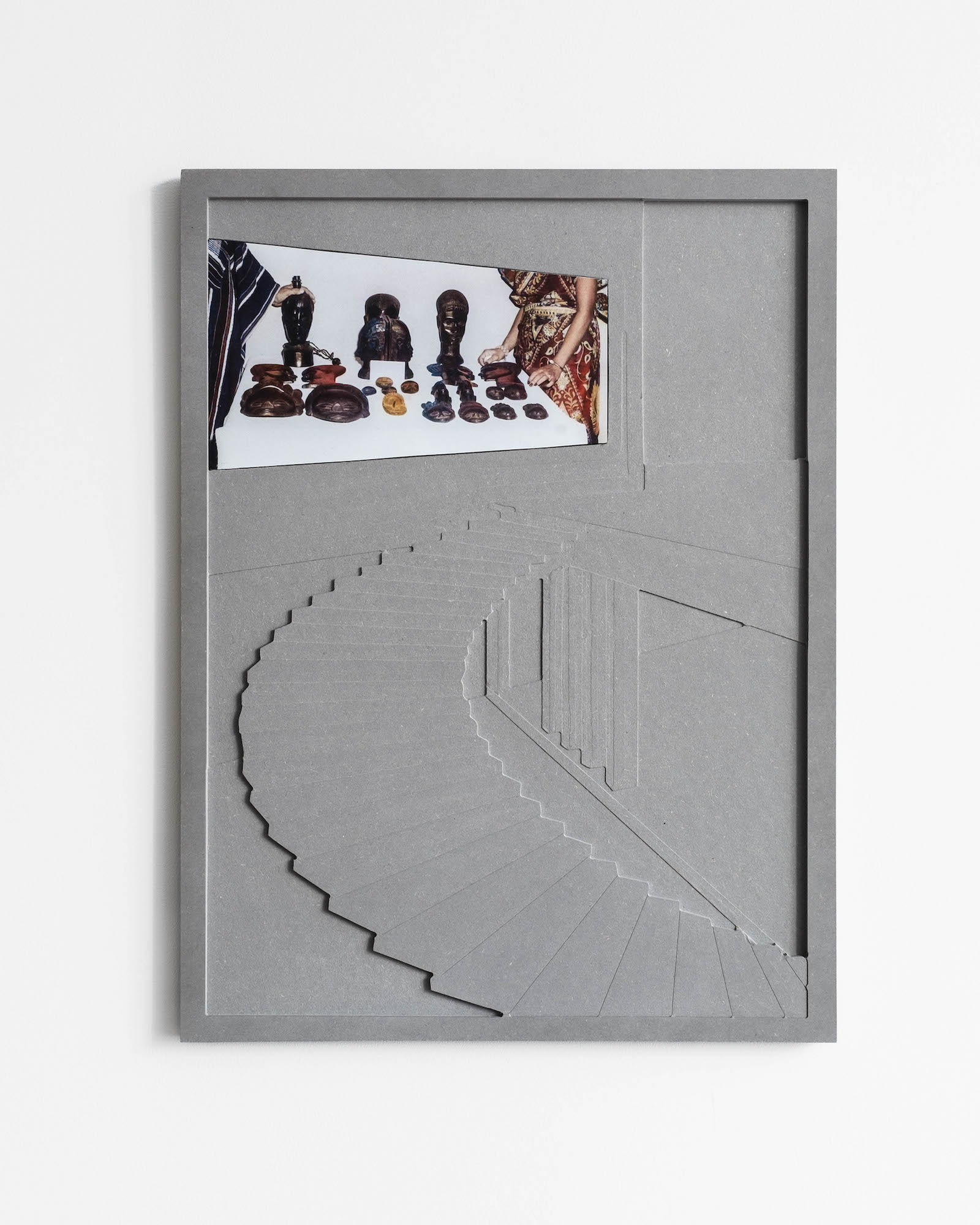

In 1816, the American Colonization Society was formed by a handful of white slaveholding politicians with the objective of repatriating free African American men to the African continent. An act of benevolence it was not. Established out of the myth of Black inferiority and a foolish belief, on the part of some abolitionists, that African Americans who had long lived in the United States would fare better in a colony they knew little about, the American Colonization Society established an African American settlement on the coast of present-day Liberia—a country whose architectural history Collins explores further in low-relief works on the gallery’s walls. Although many settlers died as a result of ecological and biological dissonance, the remaining population of settlers believed themselves superior to people indigenous to the land and, in a case of lateral violence, maintained minority political and economic control, which led to power struggles, coups, civil wars, and economic mismanagement—“a failure to think beyond the limitations of this world,” Garvey notes.

Coleman Collins, Untitled (EJ Roye), 2025, engineered wood, UV print on Dibond 24 x 18 inches[courtesy of the artist and Brief Histories, NY]

Coleman Collins, Untitled (Ducor), 2025, engineered wood, UV print on Dibond 24 x 18 inches[courtesy of the artist and Brief Histories, NY]

Nothing breeds success like failure, and as the previous efforts at absconsion floundered due to constraints inherent to the body and its cognitive processes, Garvey’s solution, offered in the last few minutes of the film, concerns the body’s shedding. The narrator, as Garvey suggests, can opt out of the body-as-vessel and seek security, instead, in the digital. Syms’ The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto resurfaces: “dream of utopia can encourage us to forget that outer space will not save us from injustice.” Does that claim apply to cyberspace, too, where biased machine learning systems deployed in health care, policing, and government policy disproportionally harm communities of color, and where misinformation and its callous outcomes thrive through deepfakes, outrage-fueled algorithms, and lax content regulations? The narrator proceeds.

Whether the digital is indeed that sought-after utopic space of Black liberation remains uncertain; The Upper Room ends before it can make an edict. Collins purposely situates his work within these interstices, between question and answer, reality and fiction, thus compelling viewers to play an active role in narrative production through naïve confidence or dubious repudiation. A reminder, perhaps, of the function each of us plays in the pursuit of Black emancipation: as an aid to its impediments, failures, accomplishments, and possibilities.

Coleman Collins, The Upper Room, installation view, 2025 [courtesy of the artist and Brief Histories, NY]

Sasha Cordingley (she/they) is an arts and culture writer born in Hong Kong, raised in the Philippines, and residing in Brooklyn, NY.