Office Landscaping—A Genealogy of Corporate Critique

Andrew Norman Wilson, Uncertainty Seminars, 2014, channel HD Video installation, color, sound, 12m 55s [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

I. Ironies Disruptive to Taylorism

Since the introduction of pop art, a genealogy of artists has worked through a variety of strategies in relation to the aesthetic language of corporations. This appropriated dialect of corporate critique uses the aesthetic tropes of corporate design, brand identity, and workspace ephemera—including its software—to produce ironic works of critical estrangement. The lineage of this ironic corporate aesthetic has not yet received the necessary contextualization and analysis needed to discuss it adequately, in part because such practices are often grouped within and discussed alongside broader conceptual movements.

Despite not being considered a movement in its own right, the utility of corporate aesthetic appropriation has retained relevance in the decades since Warhol. It continues to be a pertinent method that is capable of addressing the hypercommodification of the art market, the pressures of professionalization and self-exploitation, and the feudalistic architectures of post-capitalism.

Regardless of whether corporate critique has proved itself as an –ism, it has demonstrated itself as a resilient, recurring form and has continually adapted to critique corporate influence through the decades and has found renewed urgency as a means to directly examine the languages of desire and power produced by corporate culture through examination of the neoliberal placating, falsity, and sociopolitical implications of corporate allyship; the atomized and individual labor of private contractors; the shift of the workspace from cubicle to campus; and the cloaking of Taylorist ideologies.1 within the aesthetics and languages of wellness.

After World War II, and during the time that New York emerged as a center for business, finance, and culture, artists and corporations began engaging in a protracted, reflexive pantomime of one another. As American artists increasingly viewed their role as that of cultural producers, their gestures of resistance were largely subsumed—another example of capitalism enfolding its own critique into new modes of consumer expression. Although corporations romanticized artists’ exteriority and bohemianism, they simultaneously coopted artists’ aesthetics with patronage, theft, or both to monetize resistant aesthetics and create consumer desire.

Since the 1960s, artists have attempted to develop ethical collaborations with the corporate sphere. The Artist Placement Group, for example, focused upon embedding avant-garde artists within companies as an act of culture jamming. In turn, corporations have sought out beneficial collaborations with artists. Numerous residency programs, such as Nokia’s Bell Labs, have been developed to introduce artists into the corporate space and disrupt the assumptions of corporate research teams.

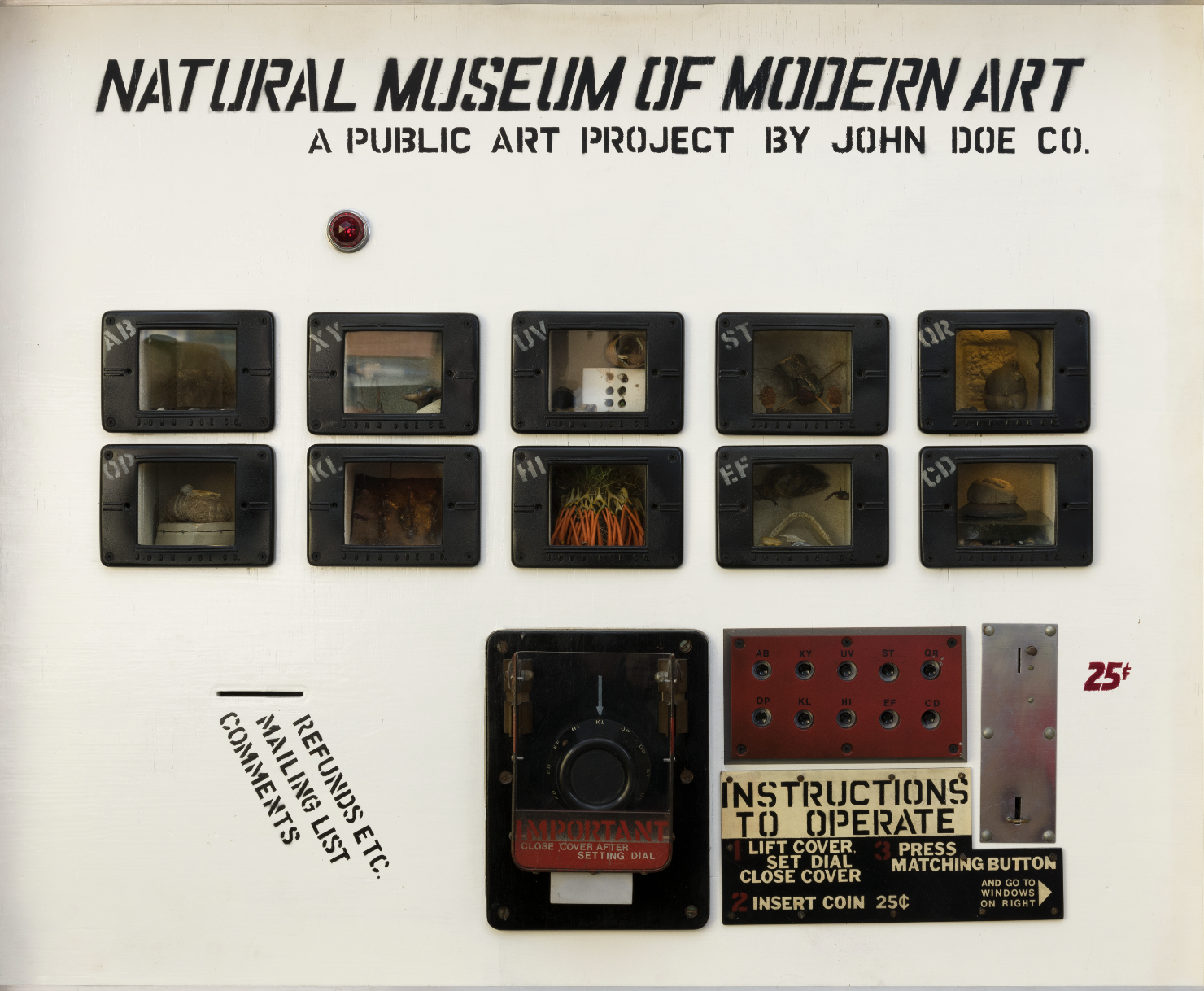

Carl Cheng, Natural Museum of Modern Art, 1979, coin-operated console, two canopied windows, sand table, 39.75 x 48.25 inches [photo: Jeff McLane; courtesy of the artist, and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles]

But corporate critique is primarily a language of artists who remain outliers, positioned at a distance that informs their critique, which is most often expressed through a parodic language of artifice. This artistic lineage perhaps originated in 1967, when Carl Cheng invented The John Doe Company. Cheng, an early adopter of the use of plastics within sculpture—specifically for modes of display and vitrines—used the company as an armature to create objects that destabilized the boundaries between sculpture and product. In a series of specimens, machines, and kits, Cheng imagined a near future—or a defamiliarized present—that offered an ironic return to nature through an ersatz gateway. The adoption of the ironic company as artifice, importantly, allowed Cheng the ability to continue creating work during the Vietnam War, a time of extreme discrimination against Asian Americans. Cheng understood that the corporation provided both camouflage and a point of access to American culture.

Such relationships between corporate structures and artist practices continued in the 1980s, with the commodity kids of the post–pop art Reagan years. Movements such as neogeometric conceptualism and Pictures Generation artists represented the totalizing nature of commodity culture and how it had reduced human relationships to forms of exchangevalue. Flashes of corporate irony during this decade delved into the ways that consumer goods had been integrated into personal and cultural identity. Ashley Bickerton’s Tormented Self-Portrait (Susie at Arles) (1987–1988) is one such early gesture, which reconciles the Warholian readymade with the graphic directness of Barbara Kruger. By presenting identity and the body not as discrete entities but as socially negotiated collages, Bickerton created an industrial reliquary, branded with logos and products to be understood through a consumerist perspective. Canadian artist Alan Belcher’s oeuvre similarly dealt with branding’s influence on constructions of identity.

Corporate critique often occurs through collectives. In its earliest iterations, collectives embraced the framework and language of advertising to divert mainstream attention and desire toward messages of social critique. The work of artist collective General Idea (1967– 1994) was radically polyphonic, but at times it crossed over, into the ironic use of marketing and corporate aesthetic through pamphlets and ephemera that performed parodic self-marketing and promotion.

Ashley Bickerton, Tormented Self-Portrait (Susie at Arles) #2, 1988, synthetic polymer, bronze powder, and lacquer on wood, anodized aluminum, rubber, plastic, formica, leather, chrome-plated steel, and padded black canvas covering 90 inches x 69 inches x 18 inches, 2286 mm x 1753 mm x 457 mm [courtesy of Ashley Bickerton, and Gagosian]

Self Portrait With Objects (1981–1982) mimics a band poster—evoking pressures upon artists to self-promote and market their practices.2 During the AIDS crisis in the 80s and 90s, collectives Act Up and Gran Fury used irony as an urgent language of redirection when they created billboards and advertisements to draw attention to the plight of the LGBTQ+ community.

In the 1990s, the distance further closed between spheres of art and advertising. A group of art students from Cooper Union formed Art Club2000. Active from 1992 to 1999, Art Club2000’s first exhibition, Commingle, at American Fine Arts, Co., explored the aesthetics of Gap stores by adopting the chain’s retail display and the melancholic sexiness of its models in group-authored self-portraits. In Invitation Image: Untitled (Conran’s 1) (1992– 1993), the group lounges about a luxurious loft, seemingly bored, surrounded by Gap shopping bags that imply a post-shopping spree saudade. This gleaming detachment effectively related the mass-marketing of clothing companies to the growing pressure of self-exploitation and professionalization within elite BFA and MFA programs and increased emphasis on output and production in the studio.

ART CLUB2000, Untitled (Conran’s 1), 1992–93, color print, 11 x 14 inches [courtesy of Artists Space, New York]

ART CLUB2000, Untitled (Industria Superstudios 2/Makeup Room), 1992–93, color print. 11 x 14 inches [courtesy of Artists Space, New York]

The Yes Men, an activist-art collaboration between Jacques Servin and Igor Vamos, would often pose as representatives of major corporations or PR firms to create absurdist disruptions, often with financial consequences for the companies they pranked. Bernadette Corporation is perhaps the most well-known collective of that era to employ corporate critique as an aesthetic strategy. Founded in the early 90s, its boundary transgressions—which began as a series of parties held in downtown Manhattan, and led to the ironic incorporation and a group practice that traversed fashion, art, art dealing, book publishing, and advertising—offered the necessary fluidity to engage product design and self-promotion from various angles. Bernadette Corporation’s exhibitions are often text-heavy and present ironic installations of selfmemorializing and history-keeping, such as in The Complete Poem (2009) at Greene Naftali and in 2000 Wasted Years (2012) at Artists Space. Both explored a visual space between retrospective and luxury store.

Even as the spaces between art and consumer marketing began closing, artwork leading up to the 2000s attempted a critical distance. But after the turn of the millennium, proximity between advertising and artmaking prompted a shift toward practices that flirted with deliberate complicity. Aleksandra Mir’s 2003 book Corporate Mentality collected different strands of artistic practice that engaged corporate aesthetics in the 90s. The book republished Anthony Davies and Simon Ford’s ironic essay “Art Futures (1999),” which described a future mode of artmaking wherein “culture is now packaged and sold to a range of clients and is serviced by a hybrid professional—the culturepreneur.”3 This parodic future model recognized that the frenzied search by both artists and corporations for wider audiences was converging into a complicit future of shared goals. Slowly, the word production began replacing practice in some artists’ vernacular. International mobility within an increasingly globalized art market necessitated post-studio practices. Berlin became a hub for American ex-pats who reflected upon office jobs and American corporate culture from a distance. With a shared interest in the post-studio aesthetics of Net Art, all that was needed to produce an exhibition was a laptop and access to printing on DIBOND®.

Rather than rejecting the figure of the culturepreneur, artists interested in corporate aesthetics—particularly after the financial crisis of 2008—explored the concept. It is hard not to interpret this gesture, in some ways, as a reaction to the financial collapse, which wiped out a generation’s access to homeownership. However, the rise of this approach was also concurrent with growing influences of Facebook and Twitter. Blogging’s evolution into what would eventually become social media allowed online spaces to develop into virtual sites of cultural production—ones that could exist simultaneously as marketplaces, journals, and virtual galleries. The 00s brought the blurring of previously delineated boundaries between retail goods, fashion, and art, such as the digital native bohemianism of online pseudo-marketplace/blog/review platform/art collective DIS. Radically, the DIS collective chose to blur distinctions between contract work—whether commercial, editorial, or curatorial—and its artistic practices. For Watermarked I Kenzo Fall (2012), shown in MoMA PS1’s 2013 exhibition Image Employment, DIS presented video footage from a paid commission for Kenzo’s seasonal menswear collection. The work uses B footage of models all turning to the camera to smile, wave, and empty their pockets to heighten the repetitive and uncanny gestures of fashion commercials.4

DIS, Watermarked (KENZO), 2012, screenshots, HD video, 2m 10s [courtesy of YouTube, and HUB Institute]

DIS, Watermarked (KENZO), 2012, screenshots, HD video, 2m 10s [courtesy of YouTube, and HUB Institute]

DIS, Watermarked (KENZO), 2012, screenshots, HD video, 2m 10s [courtesy of YouTube, and HUB Institute]

DIS, Watermarked (KENZO), 2012, screenshots, HD video, 2m 10s [courtesy of YouTube, and HUB Institute]

Strategies of corporate critique seem susceptible to aspects of conceptual and literal exhaustion, and can represent short-lived interventions. In 2011, K-HOLE (2011–2016)— an artist collective/trend forecasting group—began releasing “art world trend reports” on limited-run USB drives. K-HOLE’s interest in consumer culture came from wanting something more “holistic about the inputs and outputs of what register[s] as culture.” Rather than rejecting relationships between corporate advertising and the art world, KHOLE represented a new, unironic integration of art within the spaces of advertising and consulting. K-HOLE co-founder Dena Yago has described the group’s consulting as an act of antagonism toward its clients and the process, but she also has described the consulting process as a means of creating a more fair and ethical relationship between artists and corporate sponsors—one that properly compensates artists for their labor and grants them a seat at the table.

K-HOLE, K-HOLE #3, “FragMOREtation”, 2011-2016, p.8, PDF [courtesy of http://khole.net/issues/]

K-HOLE, K-HOLE #3, “The K-HOLE Brand Anxiety Matrix,” 2011-2016, p.8, PDF [courtesy of http://khole.net/issues/]

II. The Future Quickborner Dreamed Of

The office landscape—or, as the German design team Quickborner calls it, the Bürolandschaft—has become known as the open office floor plan. It offers an important compression and heuristic of early forms of social theory and control by intentionally orchestrating space toward optimal worker performance and productivity. The open floor plan, proposed originally to reduce social hierarchies in the workplace, was instead a reinforced Panopticon of self-management and self-extraction. Harun Farocki’s film Ein neues Produkt (2012) examines the nuance and deliberateness of such choices in determining office layout. The film also reveals a desire for control and manipulation in office planning.

Artists have charted shifts within the conditions of corporate America, a path once represented by the asceticism of modernist design that became a maniacal assertion of holistic living. In the 1990s, artists appropriated the spaces of corporate America—the cubicle, the office, the corporate building—as fodder for intervention. Mike Kelley’s Proposal for the Decoration of an Island of Conference Rooms (with Copy Room) for an Advertising Agency Designed by Frank Gehry (1991) attempted to develop the conference room as an exhibition space. Andrew Norman Wilson’s early practice directly engaged corporate campus luxuries as strategic reformations of Taylorist ideas. Wilson came from a background in journalism. As a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, he became interested in information theory, ethnography, and the dynamics of corporate America. Wilson’s father worked for Kodak, a company whose mediating apparatus would determine the ways we see—and dream—in pictures.

After graduating, Wilson worked as an early employee at Google. He was in charge of the media that would be disseminated to employees on its campus.5 His most well-known work is Workers Leaving the Googleplex (2011),6 which resulted in Wilson being fired by Google. Wilson deserves further recognition as an early practitioner of office tools, which he employs to create an uncanny strangeness. His Uncertainty Seminars (2012–ongoing) create absurdist tonalities through corporate PowerPoint presentations and wellness seminars. Although Wilson has abandoned such tools—whose artifice and language became too restrictive—they proved influential and resonant to artists engaging these themes, particularly since Covid.

Andrew Norman Wilson, Workers Leaving the Googleplex, 2011, 7 channel, 2 channel, single channel HD video, color, sound, 11m 3s [courtesy of the artist]

The gesture to understand and repurpose the featureless tonality of corporate spaces has been explored in such works as Pilvi Takala’s The Trainee (2008), video documentation of a monthlong performance by the artist, in which she worked for Deloitte. There, she did no work. She often sat, staring in her cubicle, and recorded her coworkers’ reactions. In To Do List (2012–2014) by Kerry Downey, Joanna Seitz, and dancer Jen Rosenblit, the choreography creates conflict between Rosenblit’s body and the partitions of abandoned cubicles in a derelict office, wavering between gestures of antagonism, play, and surrender. In Modern Ruins (Popular Cannibals) (2014), Stephanie Syjuco presented a midcentury modern office in a state of deconstructed disarray, including a junk simulacrum of an Eames Lounger; and knock-off assemblages of high-design furniture, stacked as if in storage. This year, in Shane Darwent’s exhibition Sun Smoke at Spencer Brownstone Gallery, his repurposed awnings, discarded from closing businesses, took on a funerary tone. He arranged them in the gallery as Donald Judd–like objects of mourning. Similarly, Elmgreen & Dragset’s recent installation at Fondazione Prada, Garden of Eden, reformulated the emptiness of corporate offices amid Covid lockdowns.

III. Tech, Subcontractors, Wellness, and New Romanticism

Web 2.0 and the rise of social media created a material reality of complete subsumption, wherein all online gestures, interests, and attention are extracted and used as forms of immaterial labor. The extensive data collection that social media proliferated in the last decade seemed, for a moment, to be the final possibility of networked monetization.7 Dena Yago’s essay “Content Industrial Complex” explored the rise and implications of Instagrammable art, which she characterized as a form of UGC, or “user generated content.”

Whereas many uses of corporate critique from 2008 to 2014 engaged corporate aesthetics to expose blurred boundaries of contract work and self-exploitation, post-Covid manifestations often respond to the fault lines exposed within corporate relationships. This newest evolution of corporate critique finds renewed energy by exploring such contexts as Silicon Valley tech company culture, suspicions around cryptocurrencies, risk and uncertainty felt by subcontractors within the gig economy, and languages of wellness and virtue-signaling used by corporations. What gives this latest iteration of corporate critique new character is its attempt to reconfigure and reshape the inputs of desire that have been developed within advertising and product design, and thereby to reverse the flow of consumerism toward a more ethical conscience.

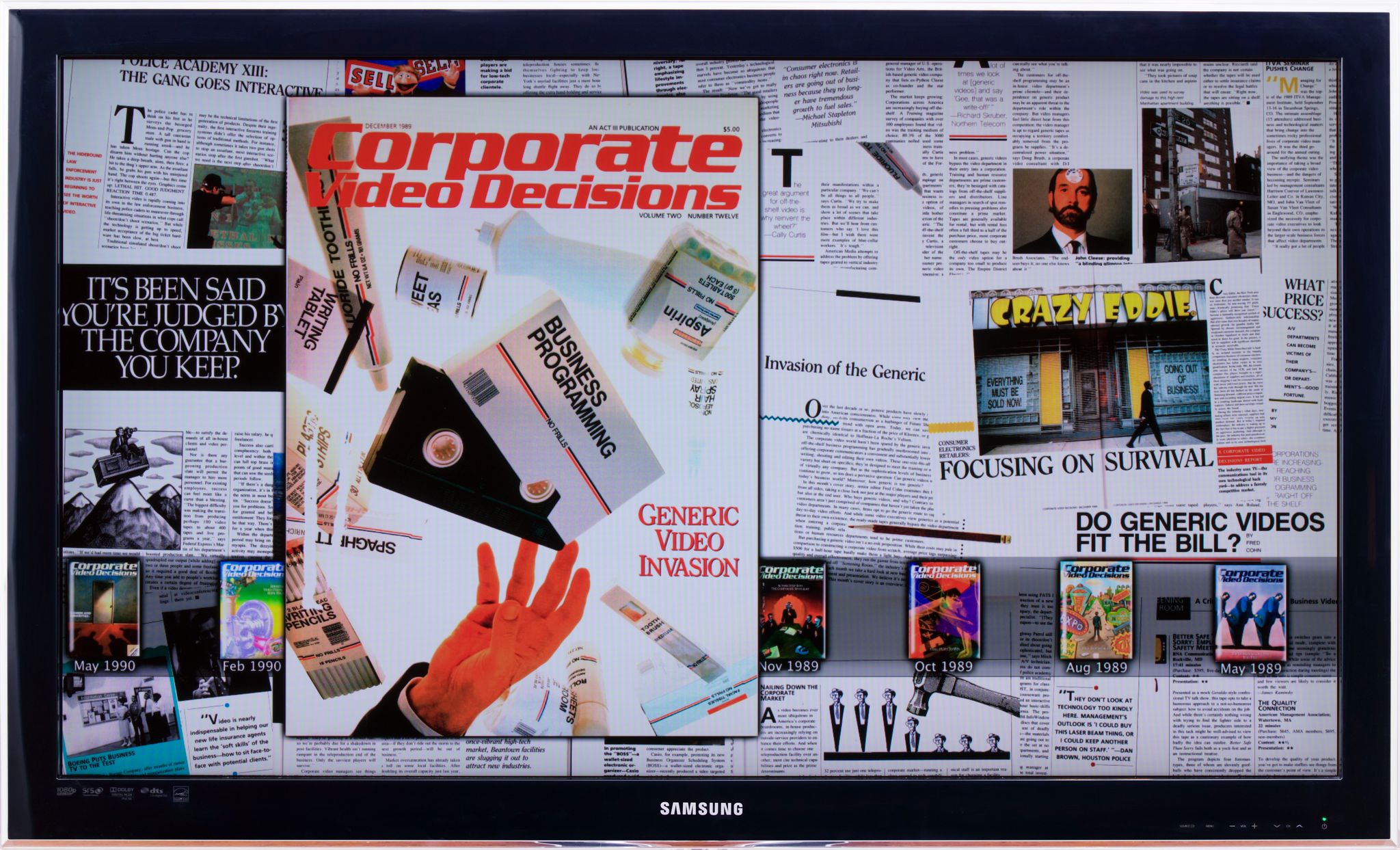

Simon Denny, Corporate Video Decisions Archive Interface Design, 2011, HD video on USB stick playing on Samsung LN46C750 46-Inch 1080p 3D LCD HDTV (BLACK), 1 m 44 s, 26.77 x 44.09 x 4.92 inches [courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York]

Simon Denny has consistently worked within the languages of corporate critique over the last 20 years. He often concerns himself with aesthetic formations of the billionaire class, the bro-tech worlds of Silicon Valley and cryptocurrency, and their competing visions of work/life balance. His practice delves into the progression of interests in corporate critique. Denny’s 13.10 Keynote (2013) is a pseudo-scheduling board marking the keynote address of Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s COO, given at the Digital-Life-Design (DLD) conference. The work was first shown as part of Denny’s exhibition All you need is data: the DLD 2012 Conference REDUX rerun, which historicized that gathering as a defining moment in the data extraction practices of Web 2.0. As part of Corporate Video Decisions (2011), his exhibition at Friedrich Petzel Gallery, Denny printed the website of Diligent Board Portals to create an anxiety-inducing world of graphs, logos, and copy machine banners—a frenetic language of corporate dada. These elements, and their effects, are similarly explored by Michael Bell-Smith in his video De-Employed (2012). In this work, Bell-Smith mines the aesthetics of clip art, image and audio presets, and the built-in tools of graphic software.

One strategy of corporate critique centers the experience of the subcontractor—bodies placed at risk to do what society defines as both essential and unskilled, exemplified by Josh Kline’s Saving Money with Subcontractors (FedEx Worker’s Head) (2015–2017).

Andrew Roberts’ work La Horda (2020), in the current Whitney Biennial, presents a postapocalyptic future of the Pequod Company, wherein subcontracted Amazon delivery drivers are now zombies who sorrowfully explain that your packages can no longer be delivered on time.

Débora Delmar investigates idioms of desire and wellness in such installations as Working Conditions (2021). She formed the Debora Delmar Corp. and used it numerous times to examine the different messages of international corporate culture. In MINT, an exhibition she organized for the 2016 Berlin Biennale, Delmar evokes the faux sincerity of a wellness juice bar to explore new economic channels of extraction that draw global investment. Liz Magic Laser’s In Real Life (2019) channels the anxieties produced by self-help and wellness language that often supplants balanced healthcare in corporate settings. The five-channel video installation documents five freelance workers as they speak with life coaches to develop wellness-based self-improvement plans.

A new feudalism is emerging thanks to social media and data mining’s total monetization of individual online activity, the breakdown of politics, and extreme income inequality. Businesses now assume a Total Role in Society,8 one that relies upon false advocacy, virtue-signaling, and other performative gestures to maintain a perception of credibility. This new, false relatability works to support the supposed personhood of corporations as they attempt to expand audience reach. Timur Si-Qin’s Campaign for a New Protocol (2018) exhumes desire from wellness marketing and Apple products’ minimalist design to invert the seduction of Helvetica-font marketing and redeploy it as the language of a proposed, nature-based religion. The “new protocol” presents itself as a corporation—a hack of the colors and textures of product desire—that manifests as a romanticist project, a form of creative manipulation intended to inscribe a new morality of conservation and humanism in the audience. Similarly, in such works as Corpus Oeconomicus (2021), Mathis Altmann transmutes the aesthetic—the colors and simplicity—often used to spark product desire into sculptural works that generate a sense of “we should want this.” But the works dematerialize into ruins, unraveling like a discard pile, instead of forming a finished commodity.

Timur Si-Qin, Campaign For A New Protocol, Part I, installation view, 2018 [courtesy of the artist, and Société, Berlin]

Mo Kong’s recent exhibition at the Queens Museum imagined a fictional near-future company, New Yorkoolâ, that offers its services to manage impending systemic and climatic collapse. Kong’s ambitious sculptural installation presents an indoor, mobile park as a site of reflection, a place to watch plants grow artificially under UV light. Painted black, like an obelisk or tomb, the structure itself presages design we might encounter in coming decades, one that nostalgically embraces nature and growth within the new terms of climate devastation and food scarcity. Enjoyment of the installation, or desire amid it, oscillates with repulsion, creating a conflicting memento mori and reminder that dystopic science fictions are all too near.

Ultimately, corporate critique has a genealogy, one that is cyclical and resilient, and that allows artists to engage aesthetics of control, desire, and regulation which corporate capitalist structures aim to produce. As artists work through the conditions of Covid, they are also finding ways to ironically engage new means of extraction presented by Web 3.0, and to steal attention from the coercive desire of commodities. This new romanticism, enacted through the hacking of corporate aesthetics and language, generates new mythologies, which can, in turn, inspire future corporate critiques. By appropriating the color palettes, sounds, textures, jargon, and affects that have been weaponized against consumers, artists gesture toward an ethical recalibration. Through an optimist’s lens, this artistic lineage offers to repossess corporate allyship and build ethical forms of occupational humanism.

Artist, curator, and critic Andrew Woolbright is based in Brooklyn, New York, and is an MFA graduate from RISD in painting. He is a regular contributor to the Brooklyn Rail and is currently a resident at the Sharpe Walentas Studio Program in DUMBO. In addition to his practice and criticism, Woolbright is the founder and director of the gallery Below Grand located on the Lower East Side in New York and teaches at School of Visual Arts in New York City.

References

| ↑1 | A system of factory management theorized by Frederick W. Taylor, structured to maximize shortterm, optimal worker output. Taylor would time each task in the factory, then expect workers to perform their tasks like machines, under the assumption that workers would inevitably become exhausted but are always easily replaceable. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The recent exhibition Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, curated by Gianni Jetzer and Sandy Guttman, presented a survey of artists who engaged ironically with this commodity turn in art. |

| ↑3 | “In a broad and still largely inaccessible area like culture, where many clients are uncertain and lack knowledge, and where gauging the pace of change can be a matter of survival, culturepreneurs emerged to trade access to social networks and capitalize on programming lacunae in both the public and private sectors.” |

| ↑4 | Jennifer and Kevin McCoy’s Broker, an exhibition at Postmasters Gallery in 2016, used the cadence and affect of corporate training videos to ironically train the viewer in how to influence others. Other artists have used the flat affect of training videos, such as in Harm Van den Dorpel’s Strategies (2011), which reduces the slogan “corporate motivation” to babble. 5 He jokes that, still, to this day, his most seen work is the video he made of VC Man (V.C. standing for video conferencing), an in-office tutorial series that Google employees still watch during onboarding. |

| ↑5 | He jokes that, still, to this day, his most seen work is the video he made of VC Man (V.C. standing for video conferencing), an in-office tutorial series that Google employees still watch during onboarding. |

| ↑6 | A reference to Harun Faroki’s video Workers Leaving the Factory (1995), which itself refers to Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895) by Louis Lumière. |

| ↑7 | Web 3.0 introduces a new reality of extraction, in which ownership and profit are artificially developed and engineered within completely nonmaterial zones, such as the metaverse, cryptocurrency, and NFTs. |

| ↑8 | Another ironic but ultimately prophetic notion developed in Anthony Davies and Simon Ford’s “Art Futures,” wherein “companies develop cultural missions … to build up an ethical image,” as they continue to replace roles previously held by the state, and to expand their audiences through promises of consumer community and shared goals. |