Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, 2017, installation view, Adobe Flash animation

[courtesy of the artists and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco]

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries

Share:

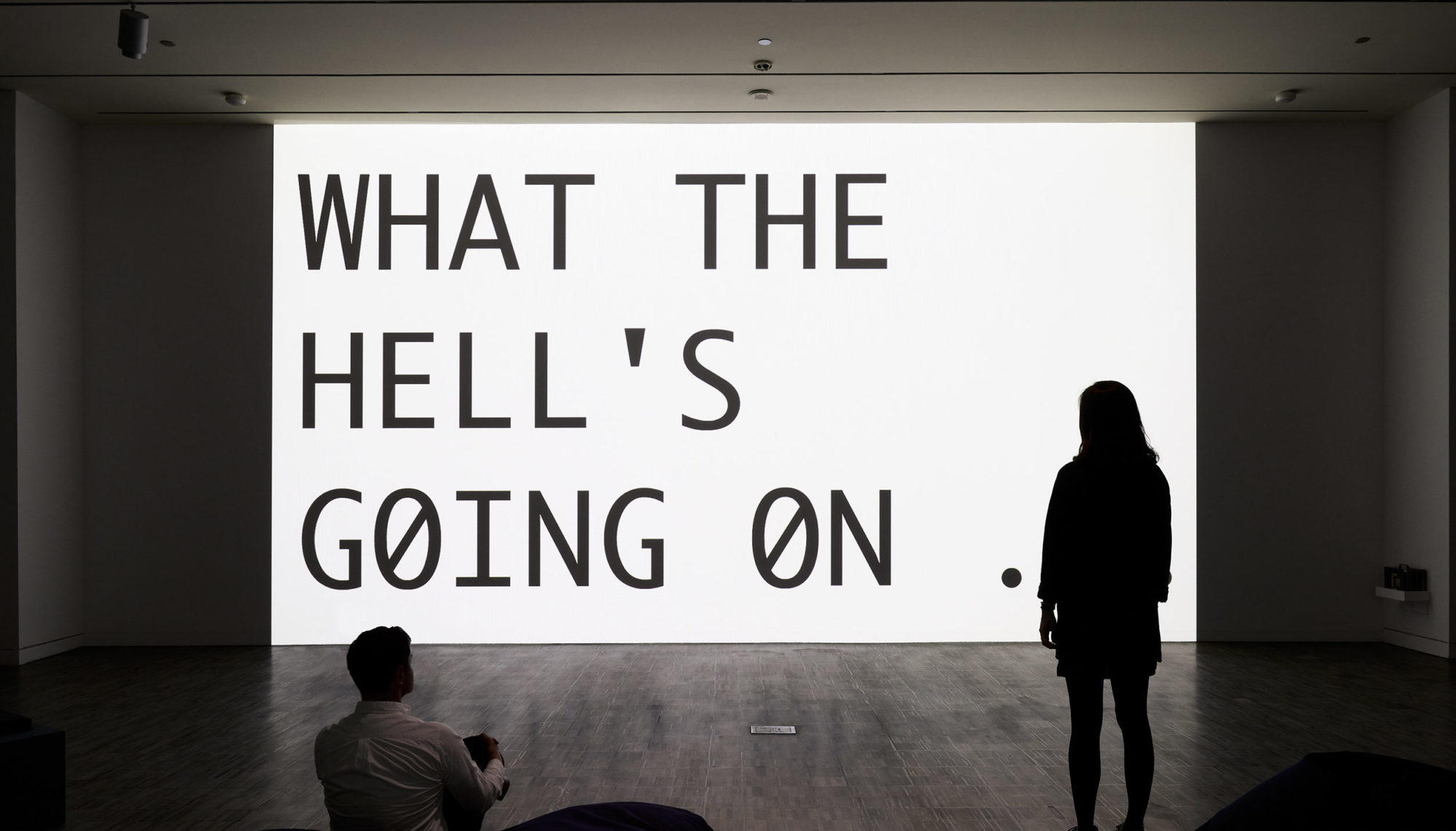

In 2000, two then-unknown artistic collaborators, Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge, submitted their work to the Webby Awards at SFMOMA, a competition for excellence in digital art. Given the limitations of the early Web, there was room for only one person’s name on the online form. Their piece won, and Chang, whose name was listed, got to travel from Seoul to San Francisco to accept the award. Shortly thereafter, the artists formalized their relationship; Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (YHCHI) was born. For nearly twenty years, the duo has been creating Flash animations of startling concrete poetry: often, black text against a white screen, dealing with anxieties of inclusion and exclusion in everyday life. While current new media work is often immersive, by way of installation, VR, and computer vision, their work has remained emphatically noninteractive, with videos that pay homage to the conventions of old film, starting with a film leader countdown before opening with the credit: “Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries presents.” From there, text zooms and flashes across the screen, keeping time with a jazz soundtrack.

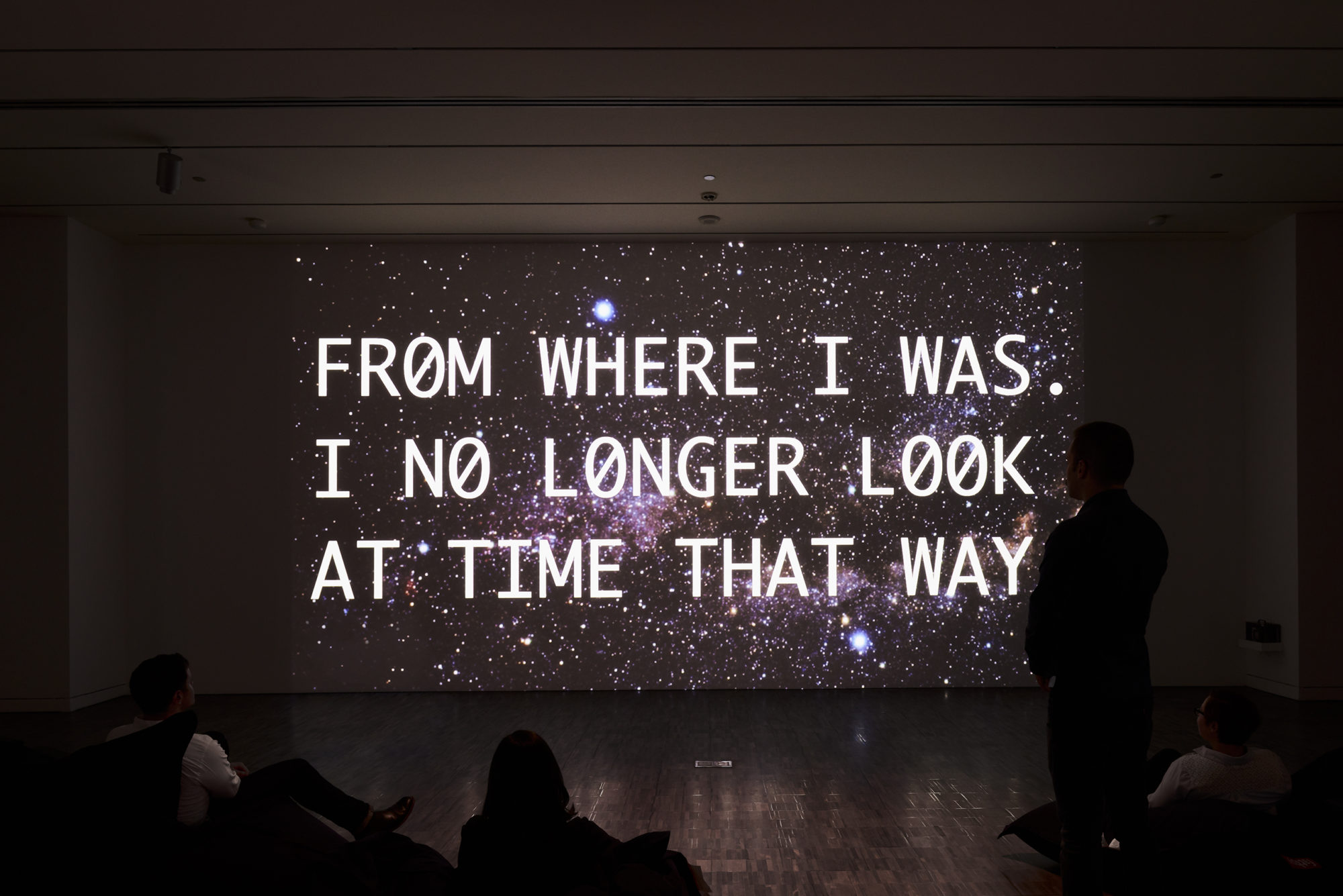

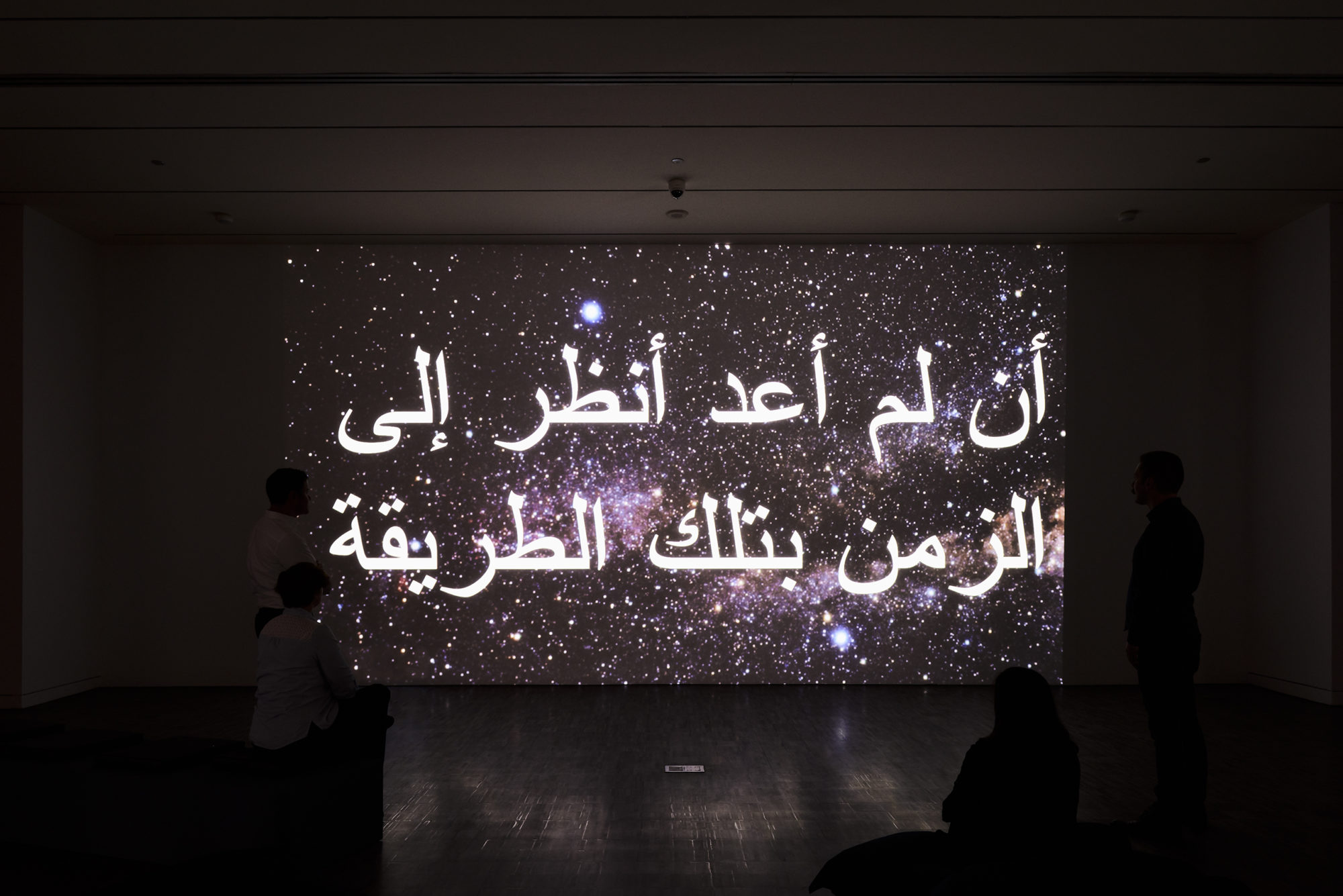

In So you made it. What do you know. Congratulations and welcome! [July 7-October 1, 2017], a new exhibition at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, this simplicity of form combined with stream-of-consciousness storytelling returns to themes surrounding the psychological pressures of being left out or left behind in a hostile world. Curated by senior educator of contemporary art Marc Mayer, the show features two floor-to-ceiling screens displaying a one-hour loop of seven videos, with one screen showing the text in English and the other in Korean, Swedish, Japanese, Arabic, Spanish, and Chinese. The loop starts with Ah; the subsequent opening credits describe as it a “public service announcement.” The story begins:

YOU’RE MINDING YOUR OWN BUSINESS, WHEN SOME GUY IN A UNIFORM — MAYBE JUST A WHITE SHIRT WITH A BADGE ON IT — SNEAKS UP FROM BEHIND AND INVITES YOU TO STEP OUT OF THE LINE AND FOLLOW HIM INTO WHAT TURNS OUT TO BE A WINDOWLESS BACK ROOM. AND HE’S ONLY DOING HIS JOB. I’D LIKE TO THINK THIS SUDDEN JAM CAN HAPPEN TO ANYONE. BUT IT CAN’T. IT JUST DOESN’T. IT WILL HAPPEN TO ME, AND, IF YOUR HEART IS RACING BY JUST READING THESE LINES, IT MAY HAPPEN TO YOU, TOO. BUT IT WON’T HAPPEN TO THEM.

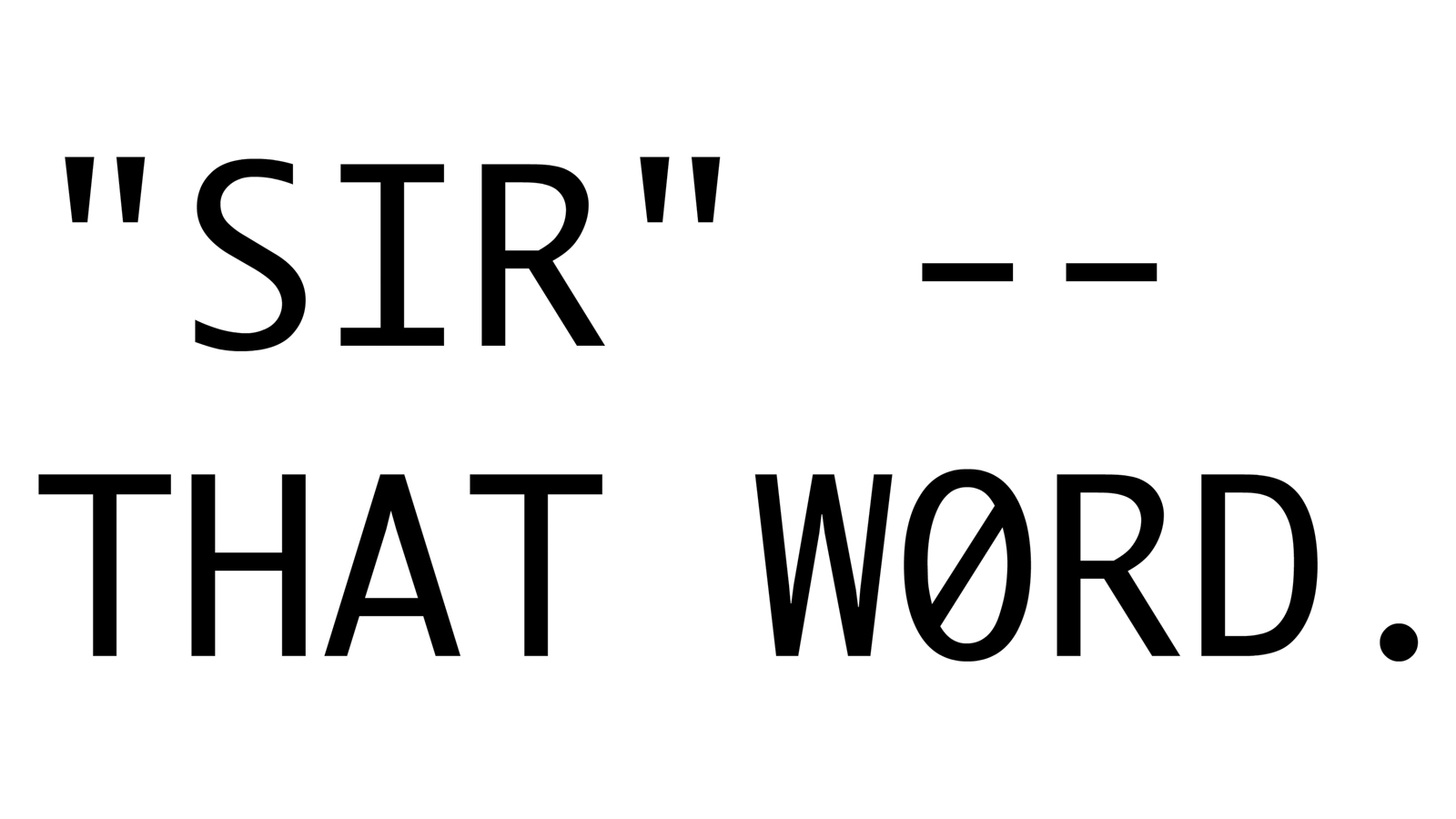

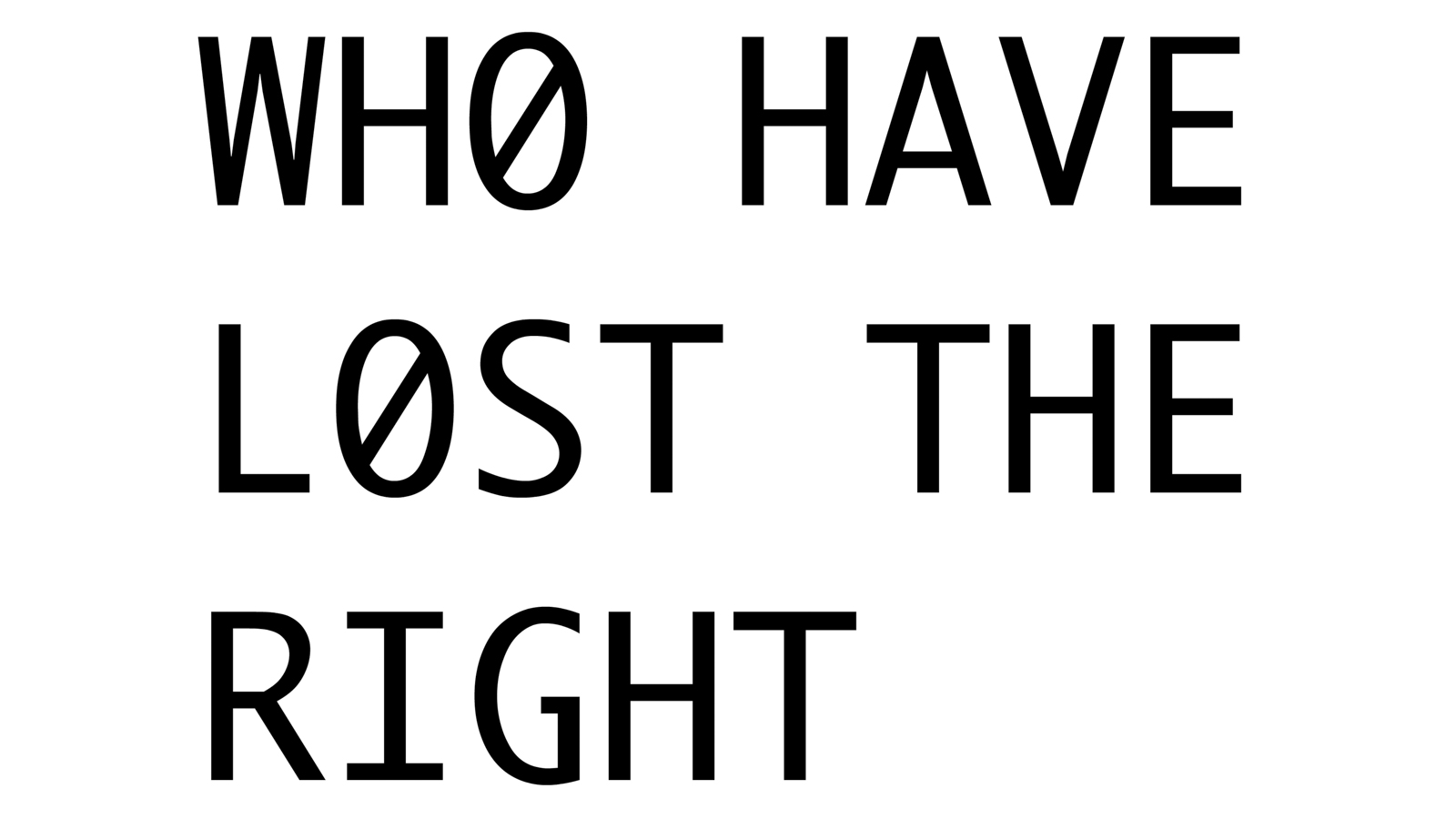

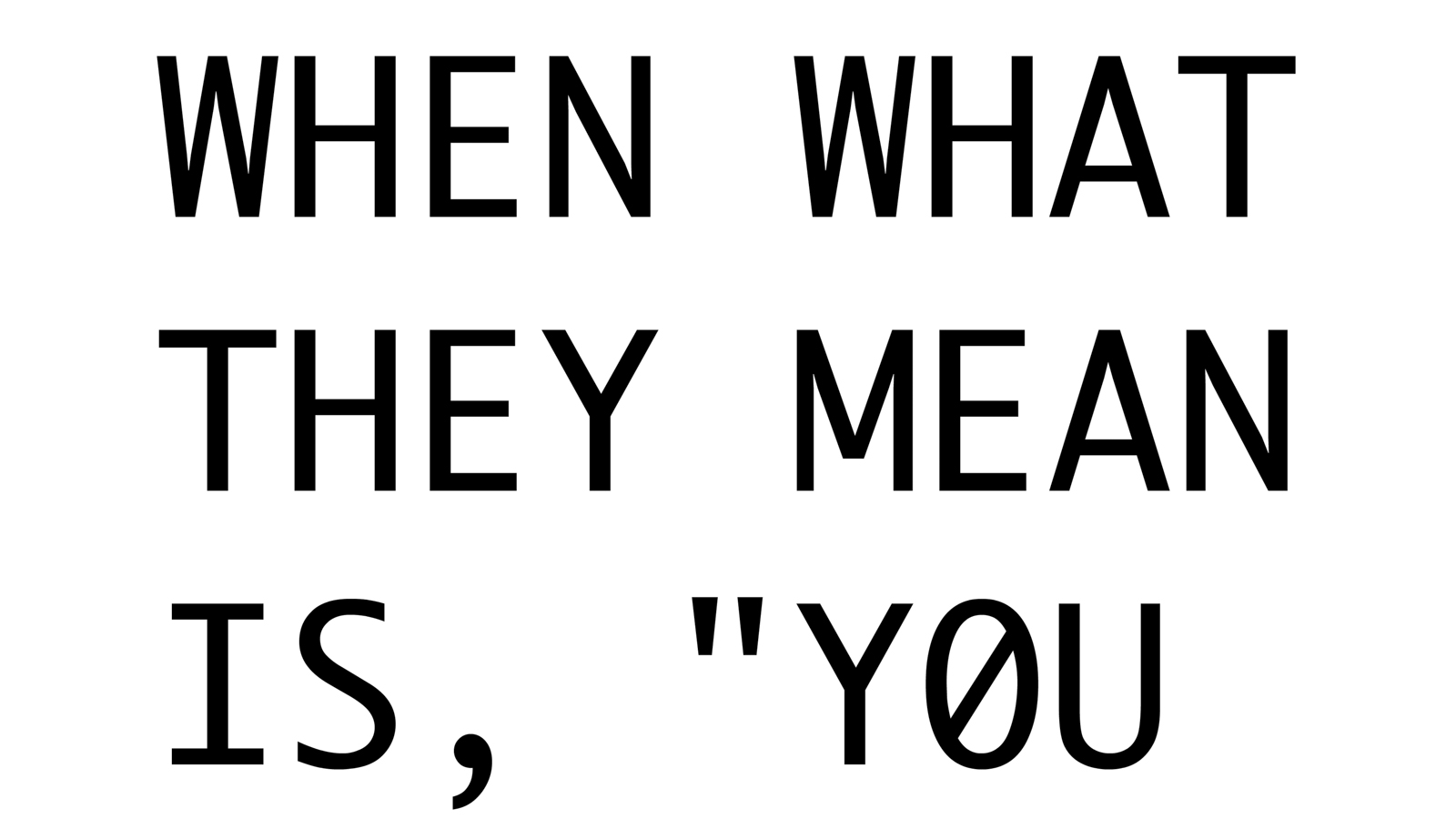

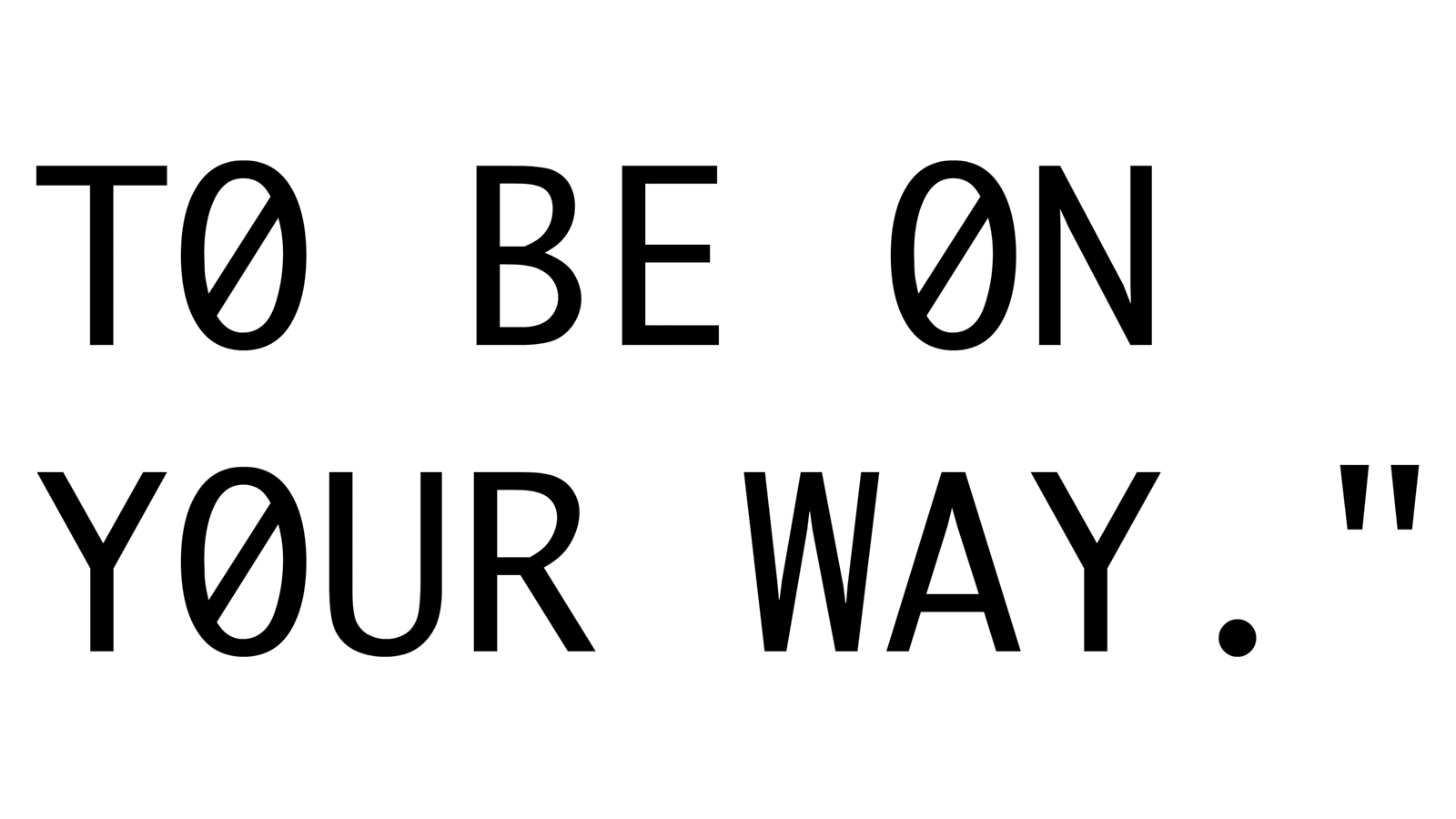

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, Ah, 2008, video stills, Adobe Flash animation

[courtesy of the artists and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco]

Unfolding over the course of 18 minutes, and vacillating between first-person and second-person narrative, the piece evolves into a blistering monologue about the narrator’s fears of the security state, detainment, and the fact of people unthinkingly carrying out tasks while participating in political or inhuman horrors. “No offense if I feel I’m all alone here,” he says. “Sorry for my lack of faith in mankind. Sorry if the good guys all seem like cowards—that’s life, as they say.”

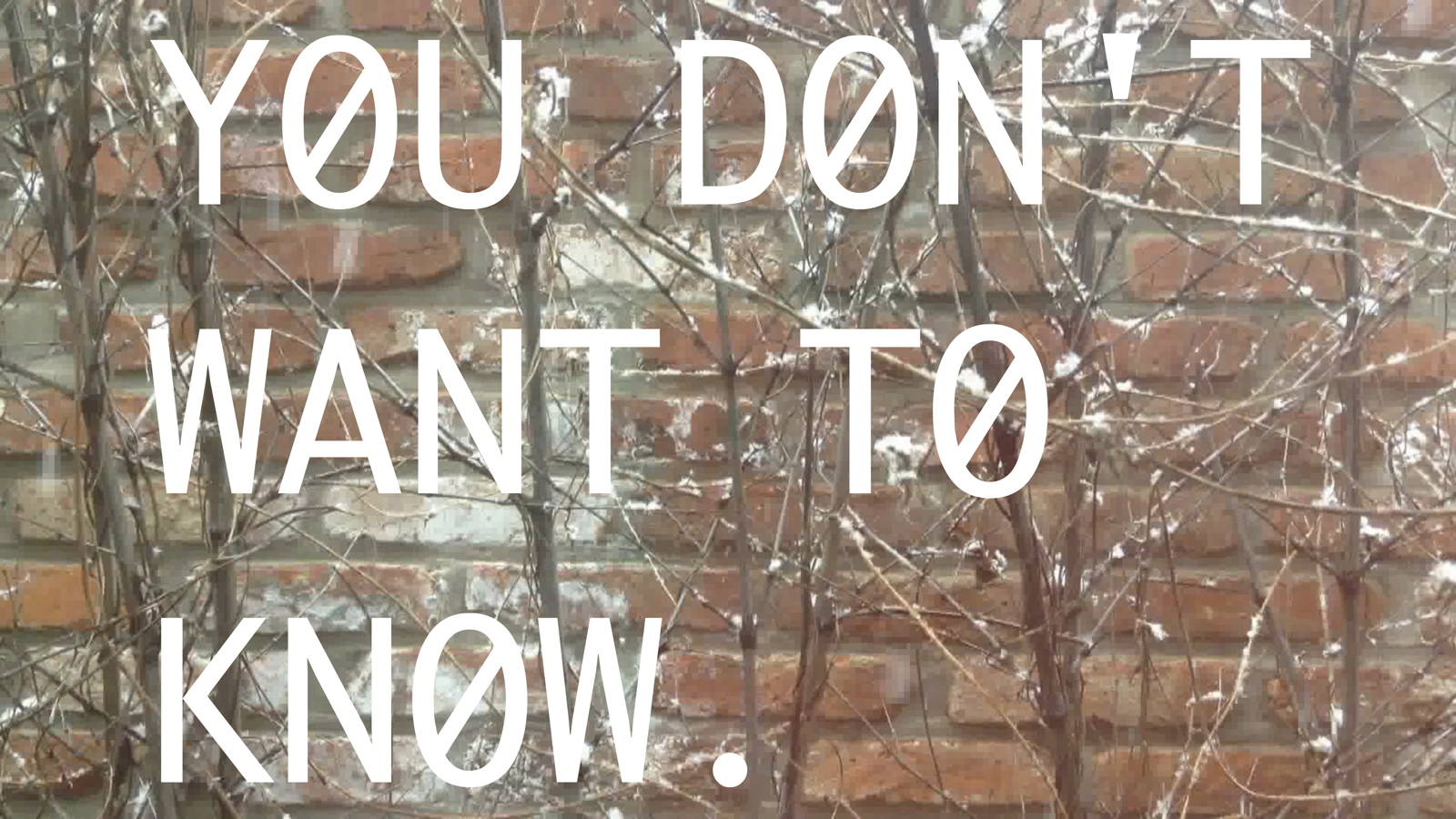

The second work in the video sequence is the exhibition’s titular So you made it. What do you know. Congratulations and welcome!—a world premiere that serves as a companion to Ah in its exploration of blunt defeatism, paranoia, and otherness. White text cascades on a backdrop of a brick wall during snowfall, a clear reference to borders in general, and perhaps to Trump’s proposed wall in particular. Created in response to the Syrian refugee crisis, the piece caustically tells prospective immigrants:

HOPEFULLY, YOU’LL SIGH WITH RELIEF AT THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE PHYSICAL VIOLENCE YOU LEFT BEHIND AND THE FREEDOM OF SPEECH VIOLENCE HERE …. HOPEFULLY, YOU’LL SEE THAT YOU’RE IN AN ESSENTIALLY BETTER PLACE. HOPEFULLY, YOU’LL BE PLEASANTLY SURPRISED. HOPEFULLY, YOU’VE GOT A THICK ENOUGH SKIN TO LAUGH IT OFF.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, 2017, installation view, Adobe Flash animation [courtesy of the artists and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco]

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’ work has always been invested in having a thick skin in the face of difficult subject matter, and an ability to laugh it off. In interviews, the artists’ responses are often so deadpan, it’s hard to tell whether they’re joking or not. Both in conversation and in their art, wit can serve as purposeful deflection. In her book Ugly Feelings, the theorist Sianne Ngai refers to “stuplimity,” defined as an amalgamation of shock and boredom.1 Ngai argues that art and literature that respond to powerlessness are able to theorize negative feelings in new and productive ways. Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries squarely operates in this brand of negativity: its tone is more irritated than angry. The repetition of “hopefully” in So you made it, and the build-up of ambivalent examples of disempowerment without resolution put the audience in the headspace of an exhausted narrator. For a body of work that gains its force in large part from its consistent, low-grade anger, the piece surprised me with explicit mention of its own sarcasm—its underlying rhetorical device—later on: “Good luck. You’ll need it. What? That’s sarcasm, a subcategory of humor. Sarcasm is—forget it.” The compressed language interrupting itself here recalls Samuel Beckett, building with statements that partially undo preceding ones, but that undoing comes from carefully adding one additional phrase at a time.2 The effect is language toppling over itself to evoke both a hoped-for numbness and the anger that lies beneath it.

In Wa’ad (2014), the artists again look at the difficulties of reconciling what people leave behind when they move to a new place with what they choose to gain from it, this time from the perspective of a female Palestinian astronaut who is attempting to build an Israeli-Palestinian utopia on Mars. Whereas Ah and So You Made It took the form of addresses to an imagined, general “you,” Wa’ad is a series of transmissions from the titular astronaut to friends back on Earth. White text is set against the backdrop of a dark purple starscape and scored to wistful classical piano in the style of Chopin. The transmissions seem to emanate from an astral void.

YOU’RE PROBABLY DYING TO KNOW WHAT IT’S LIKE FOR A PALESTINIAN AND ISRAELI TO LIVE TOGETHER. WELL, IT’S A NON-ISSUE. I NEVER FEEL ANY TENSION WITH SARA. IT’S LIKE WE’RE ON TRANQUILIZERS. EVERYTHING IS SO MELLOW. IT’S LIKE WHEN YOU’VE BEEN ARGUING (ON EARTH) AND YOU SAY, “HEY, (WHEN WE GET TO MARS), CAN WE START OVER?” AND—MIRACLE—YOU DO.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’ work has always been invested in having a thick skin in the face of difficult subject matter, and an ability to laugh it off.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, Ah, 2008, Adobe Flash animation

[courtesy of the artists and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco]

Over the course of these missives, she mentions that one of her four fellow astronauts, Ming, misses barbecued pork. She speculates that the food was cooked up by a Dutch person, since everything they squeeze out of their meal tubes has the texture of Gouda. Her admission, “I would like to sound less critical and more upbeat (after all, I chose to be here—some would say I hit the jack-pot),” would sound familiar to anyone who’s made a major life decision in hopes of a better life. She wonders about the future and history, and she apologizes for getting philosophical. Each missive ends with a variation on “With Martian kisses, Wa’ad.” Her loneliness is clear enough from the text, but it’s the silences between their display, where we are confronted with the static image of purple space for a few seconds too long, that really emphasize the emptiness and uncertainty of this Martian existence. Eventually, life on Mars turns soap-operatic:

TIME TO DROP THE BOMB ON YOU FROM WAY UP ON MARS. BUT YOU MUST PROMISE TO NOT SHARE THIS WITH OTHERS, ESPECIALLY OUR HANDLERS AT MISSION CONTROL FOR IT MIGHT JEOPARDIZE THE LONG-TERM PLANS OF THE MARS ONE MISSION. READY? WE MAKE LOVE CONSTANTLY …. LET ME REPHRASE THAT. WE HAVE SEX ALL THE TIME. ALL OF US TOGETHER, OR IN COUPLES.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, 2017, installation view, Adobe Flash animation [courtesy of the artists and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco]

In the tradition of experiments in communal living in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, and the hot tub flirtations of reality television, the forced intimacy of four urbane astronauts on Mars is understandable, if not tragic—which is only underscored by the classical piano music. The humanness of the astronauts’ impulse for connection is taken to absurd lengths, given that they are alone together, attempting utopia on Mars. Eventually, the mission fails. The astronauts await an emergency spaceship of supplies for the duration of their time there. They’ve run out of food and birth control. It ends bleakly. “Sara, ever the optimist, says if the supplies arrive, a baby would be a wonderful addition to our new world. And if they don’t arrive, she says being pregnant won’t be an issue since we’ll all be dead before the baby is born.” Simultaneously understated and overstated, wry and rueful, this transmission from a doomed utopia evokes both the gaps that haunt everyday speech and the particular bewilderment of exile.

Wa’ad marks a shift in the exhibition’s tone, moving from the opening videos’ frenzy toward a more tender and personal register. The possibility of freedom, utopia, and sex that the work entertains also appeared in The Struggle Continues, an earlier piece from 2000, whose original jazz score was updated with frenetic percussion for The Struggle Continues! (Dance Version) in 2017. Using the language of the labor movement, the video is a paean to sexual liberation. Its text urges “stark naked love” for the masses, the workers, those in the factory and in the office (though it exempts “the Buddhist monks who carry cellphones” and people with “bourgeois brains”). It calls for “A thousand love affairs for everyone!” and for “butter-basted bodies,” and urges us to “Throw the bastards out!” Effusive as it is, the relentless use of exclamation points suggests a certain desperation, perhaps an awareness of impossibility: will any of these needs ever be met?

Choosing to revise their soundtrack while keeping the animation intact in some way speaks to the artists’ view of their place in the art world. As they told me over email, “We like the art world because there’s room for everyone, even ourselves,” noting, “The whole point of Net art is that it bypasses the establishment.” In other words, they found their niche—they belong to a small community that may be anti-establishment, but that segment is still part of the art world. They use this status to their advantage. They have the freedom to experiment with new soundtracks because the art world accepts their compositions as music. In their talk at the opening, Voge said, “We never insult musicians by saying we’re musicians. The art world might say it’s ‘music’ because it’s in the art piece. Musicians or someone outside the bubble won’t embrace it.” In describing the new soundtrack for The Struggle Continues, Voge sounded almost giddy when he noted: “These days, you can invent your own musical instruments on the computer!”

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, So You Made It. What Do You Know. Congratulations and Welcome!, 2016, video stills, Adobe Flash animation [courtesy of the artists and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco]

YHCHI isn’t seeking out the latest and greatest technologies, but instead continues to use ones that enable its artists to create what they want to see and hear, as long as, in Chang’s words, “it’s cheap and easy.” At the pair’s exhibition opening at the Asian Art Museum, Voge mentioned that he felt his and Chang’s methods were validated by the advent of YouTube. Twenty years ago, they wanted to provide a full-screen video experience without the user needing to download a video on a 56k modem. They understood people’s attention spans. Viewers may not wait for a download to finish, but they would watch text pieces—even when the text sometimes comes at them so fast, they can hardly glimpse it. The duo still works in Flash (though for the exhibition, they’ve converted their videos into Quicktime files). In light of Adobe’s recent announcement that they plan to discontinue Flash by 2020, the artists are considering learning a new programming language or commissioning an app that will allow them to continue to create in their signature style.

This sense of themselves as outsiders, facilitated by accessible, low-cost, easy-to-learn, software, resonates with YHCHI’s chosen narrators, whether their voices are broadcast from Mars or a TSA checkpoint. These pieces are broadly about freedom of movement—as an ideal and as a practice, in private and in public—that can have heavy consequences for anyone seeking to break with the status quo.

At a moment when we consume more text than ever, skimming more than reading, the work of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries is radical in that it forces us to read on the artists’ terms. Sometimes text is programmed to appear in groupings of one or two words that fill up the entire screen; they may be followed by a long paragraph, then maybe a brief pause. Like the looped ellipsis that indicates someone is typing a text message—but somehow still more suspenseful—this effect holds our attention. Where most of our back-and-forth communication does not happen at the same moment in time, processing a dense text synchronized with sound in real time requires all of your mental energy in that moment. Blink, and you might miss a passage, though that’s also par for the course. We’re not computers streaming files, we’re humans with our own selective attentiveness. We want to listen and feel for each other and really capture the emotional payload of what is being said, but instead offer a cursory scan, an Emoji, a read receipt. When I first settled into one of the blue beanbag chairs at the exhibition, I prepared to take down notes for this piece and pay attention to the oncoming text. I couldn’t do both at once, so I recorded video instead, again limited by how long I could physically hold up my camera before someone said something. I was relying on technologies other than my brain. Upon coming to this realization, I put my phone down and gave in to the textual onslaught. Taking in the minimalist work of YHCHI had slowed me down. How often does that happen?

Blythe Sheldon is a writer and technologist living in Oakland, CA.