Carlos Leppe, Las Cantatrices, 1980, multi-channel video [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

Yo soy mi padre: Carlos Leppe’s Transgressive Masculinities

Share:

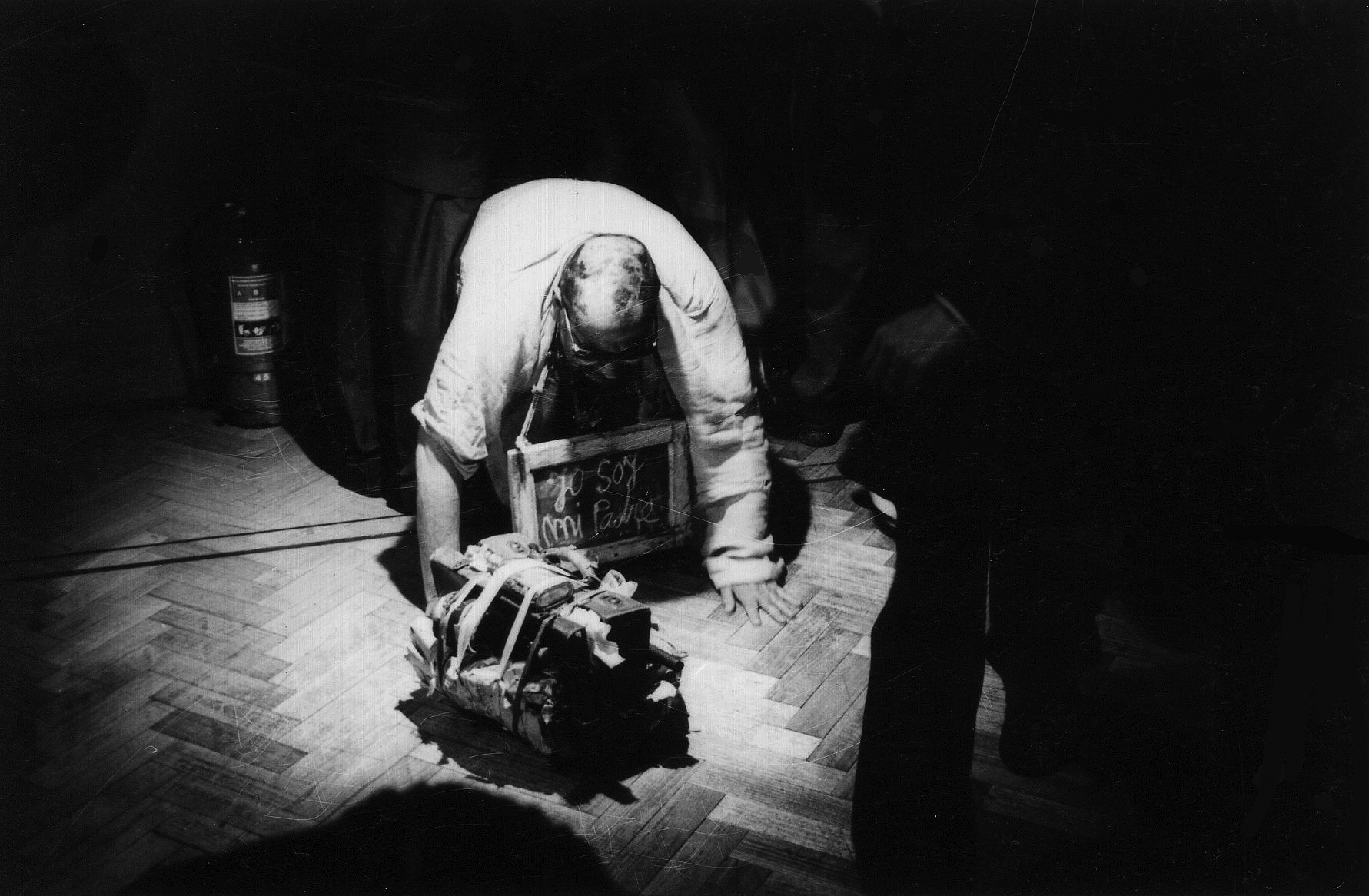

On the night of October 19, 2000, some 10 years after the fall of Chile’s military dictatorship, artist Carlos Leppe pulled up to the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago de Chile, shuttled in the rear of a taxicab. A soft waltz hummed on the car’s radio as he emerged from the back seat, the phrase “Yo soy mi padre” (“I am my father”) scrawled on a chalkboard fastened around his neck. With dogged determination, Leppe dropped to his knees, then to all fours, and crawled into the museum, followed closely by a transfixed audience.

Leppe eventually arrived at the gallery that contained one of his sculptural installations: a towering mound of hair surmounted by a small plaster statuette of the Virgin Mary. Sitting with his back against this shoddy monument, Leppe began to sob. He cried out for his mother, smeared feces atop his head, and crowned himself with a golden phallus. His attitude shifted as the performance unfolded: at times wry, hysteric, oracular, bestial. Suddenly, Leppe’s body went limp and lifeless. Two assistants pulled him by the arms, through the galleries, and out the front doors, to place the artist back into the taxicab by which he arrived.

Yo soy mi padre—Leppe paraded this statement of patrilineal influence throughout the happening, though with time its handwritten declaration smudged and faded into illegibility. His performance actively troubled glorified visions of patriarchy and virility represented by this contested mantra. Amid his hyperemotional state, self-defilement, bastardization of phallic forms, and the work’s flaccid denouement, Leppe assailed the often-aggressive construction of hegemonic masculinity in Chile. Here, as in many other works beginning in the 1970s, he conjured paternal figures—be they familial, social, or political—to challenge the Chilean national image under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

Carlos Leppe, Los Zapatos, 2000, performance [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

Across photography, film, sculpture, and performance, Leppe interrogated the torturous climate of Chile’s authoritarian regime from 1973 to 1990 by staging and restaging trauma, desire, nationalism, and the body. Throughout his practice, Leppe maintained an expansive relationship to genderqueerness and dissident sexualities. He sought to perform “from the crisis of sexual identity … from the act of transvestism, from biography itself with all its patches.” Through this very embodiment of unstably sexed and gendered selves, he enacted a dual critique of patria (fatherland) and patriarcado (patriarchy) by abusing the symbolic connection that equated maleness—and relatedly, Chile’s military dictatorship—with notions of power, stability, and control.

Leppe’s artistic career developed during a period of immense political, social, and economic rupture in his home country. Leppe, born in 1952 in Santiago, entered the fine arts program at the University of Chile in 1971, just one year after the socialist Salvador Allende took office as president. In September 1973, a US–backed coup, led by armed forces, overthrew Allende, and enabled Pinochet’s rise to power. By the time Leppe began performing in the Chilean cultural scene the following year, he had witnessed the state give way to a despotic regime maintained through censorship, surveillance, torture, secret policing, forced disappearances, and executions.

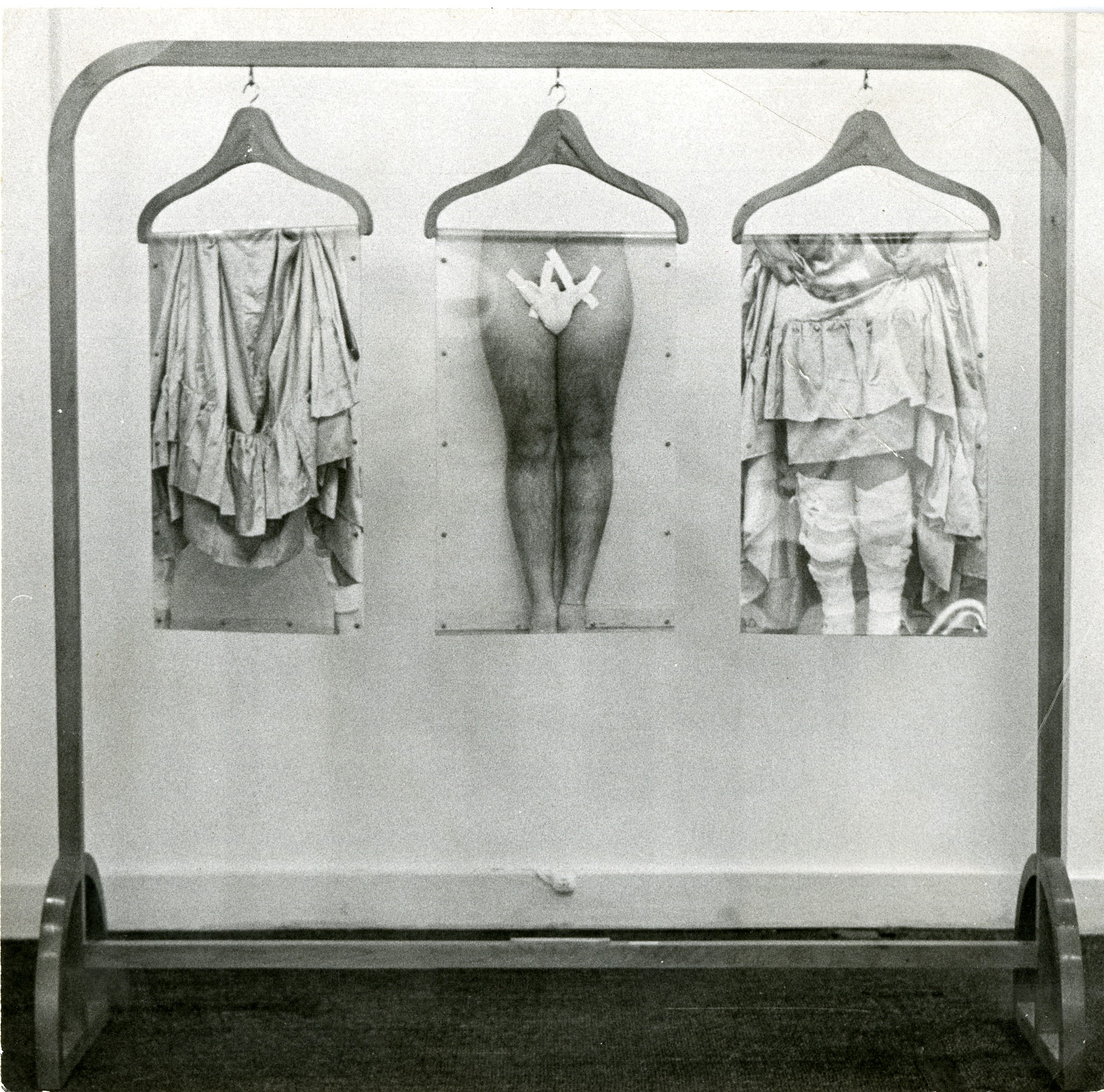

Carlos Leppe, El Perchero, installation view, 1975 [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

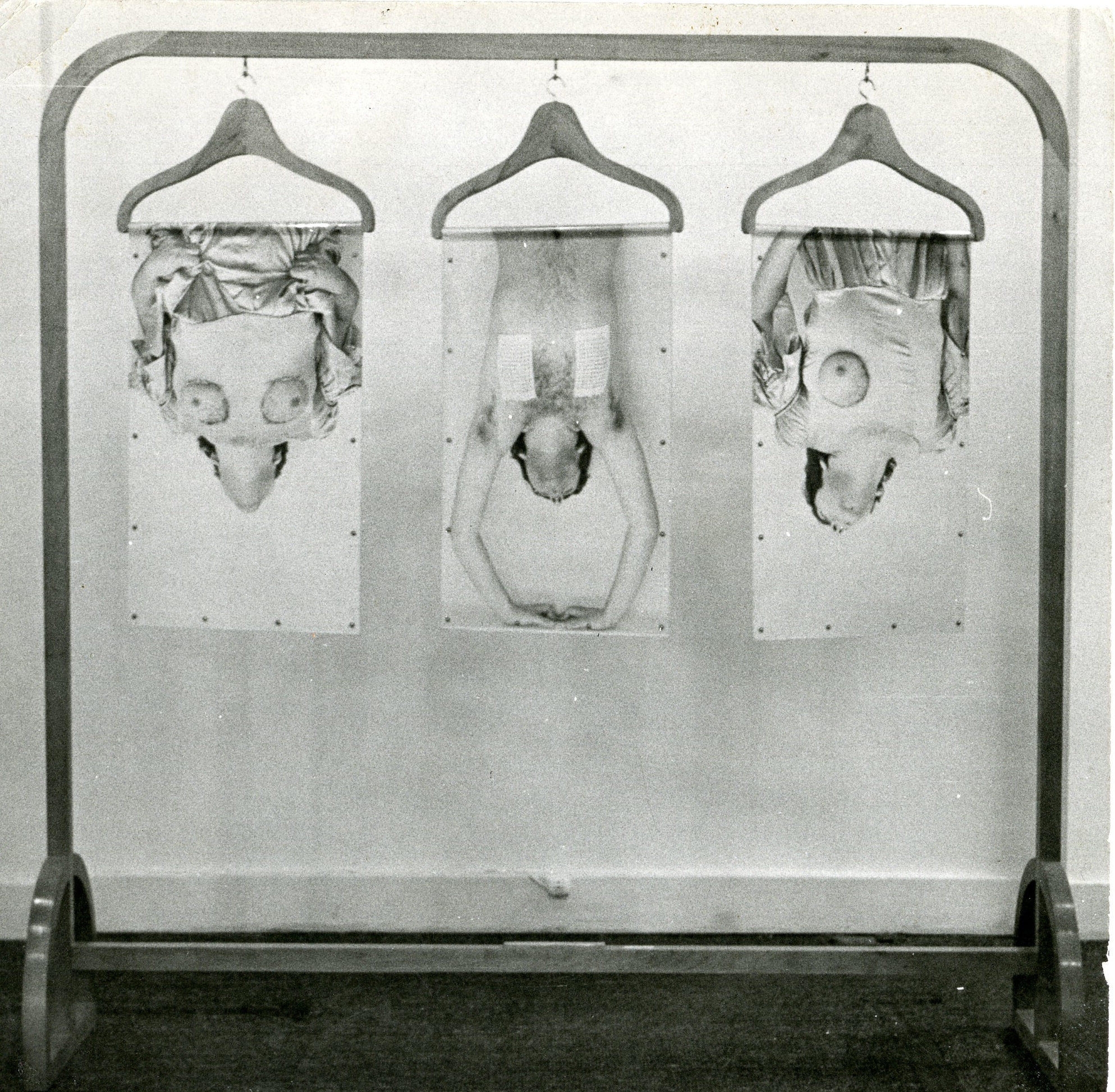

El Perchero (The Coat Rack) (1975), one of Leppe’s earliest works from this period, recorded the interrelated violence of political authoritarianism and normative systems of sex, gender, and sexuality. The photo-based installation features a wooden clothes rack and three stationary hangers draped with an equal number of life-sized self-portraits. In two images, Leppe wears a long satin gown. At the chest, one or both of his nipples protrude through circular openings, creating the appearance of breasts; in one, Leppe hikes up his skirt, revealing his bandaged legs. These prints flank a central photograph in which the artist appears nude, but for strips of gauze that cover his nipples and genitals. In each, Leppe contorts his form, twisting and cocking his head upward to such an extreme that his standing body, suspended over a clothes hanger, seems to succumb to gravitational pull.

Across this triptych, Leppe simultaneously confuses and inhabits multiple gender signifiers: nipples, breasts, and penises—visible, forged, and concealed—enter into a mutable corporeal lexicon. El Perchero divides the image of Leppe’s body/ies into a series of upper and lower halves, fracturing physical markers of sex or the easy status of a singular, definable bodily form. Through the household garment rack, which doubles as a surrogate torture apparatus, the artist alludes to the quotidian nature of violence under dictatorship. The installation evokes an abductee laid bare and surveilled—by a military state and the cisgender and heterosexual logic on which it relied—and yet, its dysphoric language transforms Leppe into a mutable and unruly subject.

Carlos Leppe, El Perchero, installation view, 1975 [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

Leppe’s exploration of gender and sexual difference coincided with Chilean authorities’ widespread attempts to codify a set of normative body politics and to construct an illusion of national unity and might. While traditional gender and family roles—seen to bolster labor practices, economic gain, nation-building, and moral fortitude—emerged as important tools in fostering a collective sense of Chilean strength, the very fact of trans*ness and gender noncomformity (as well as the discourse that surrounded them) created precarious models of national belonging. Under Pinochet, a constellation of artists produced works around lived transgender and travesti experiences in Chile, including disabled painter Lorenza Böttner; gender-bending performance duo Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis (Francisco Casas and Pedro Lemebel); and photographers Paz Errázuriz and Leonora Vicuña. Leppe, as a queer, cisgender artist, invoked trans*ness as a destabilizing force, performing gender and the national body to a point of rupture.

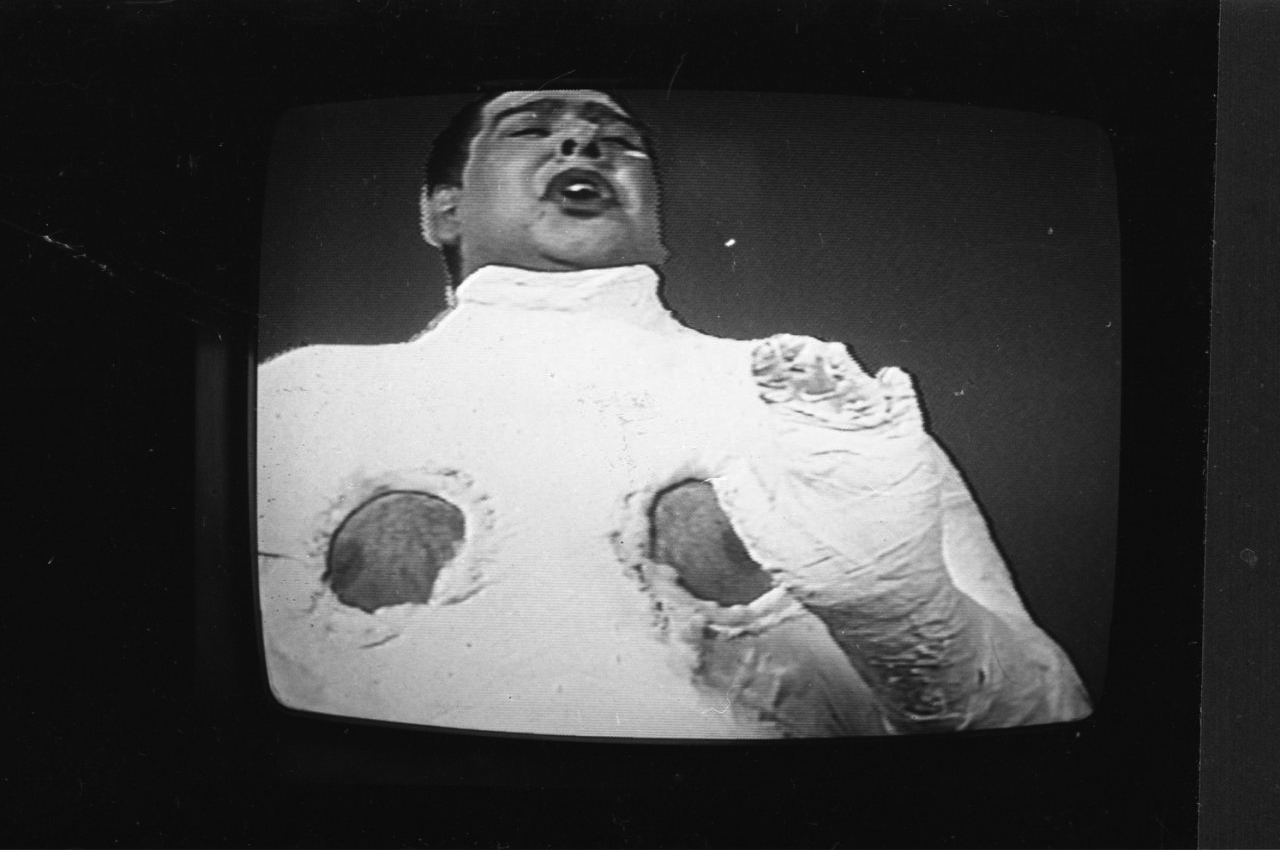

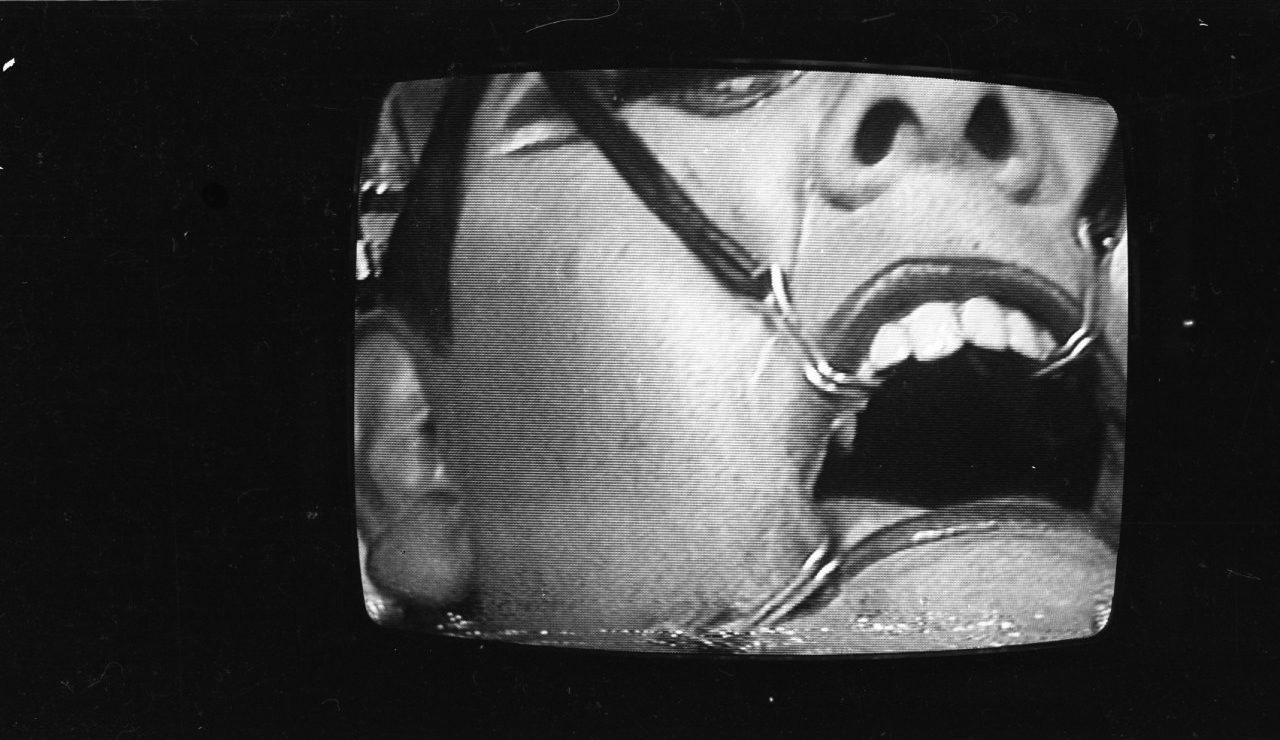

In November 1980, two months after Pinochet passed a new constitution legitimizing his regime, Leppe premiered the video work Las Cantatrices (The Opera Singers). This multichannel film includes three monitors showing Leppe in a rigid, full-body plaster cast with recesses that alternatively reveal his belly, legs, and breasts. He lip-synchs to a continuous soundtrack of operatic arias, complete with dramatic expressions, performative bravado, and an exaggerated faceful of makeup. At different moments in the footage, Leppe appears with hooks clasped at the corners of his lips, prying his mouth open as his belting builds. A fourth video spotlights the artist’s mother, Catalina Arroyo, who recounts the challenges of giving birth to Leppe—including the use of “these horrible forceps: an enormously big little body”—and of motherhood.

Carlos Leppe, Las Cantatrices, 1980, multi-channel video [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

Carlos Leppe, Las Cantatrices, 1980, multi-channel video [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

Although Las Cantatrices posits a lineage of personal and collective traumas—passed down from mother to son, from state to subject—the work also captures the ways bodies hold pain and pleasure in one synchronized breath. In his three musical performances, Leppe invokes the visual language of BDSM through images of bodily confinement, contortion, and rhapsodic ecstasy—belted vibratos that, at moments, dissolve into open-mouthed cries. This subtext of sexuality, desire, and pain, coupled with campy theatrics and slippages of flesh, function to (homo)eroticize tyrannical violence, queering and emasculating the apparatus of political control.

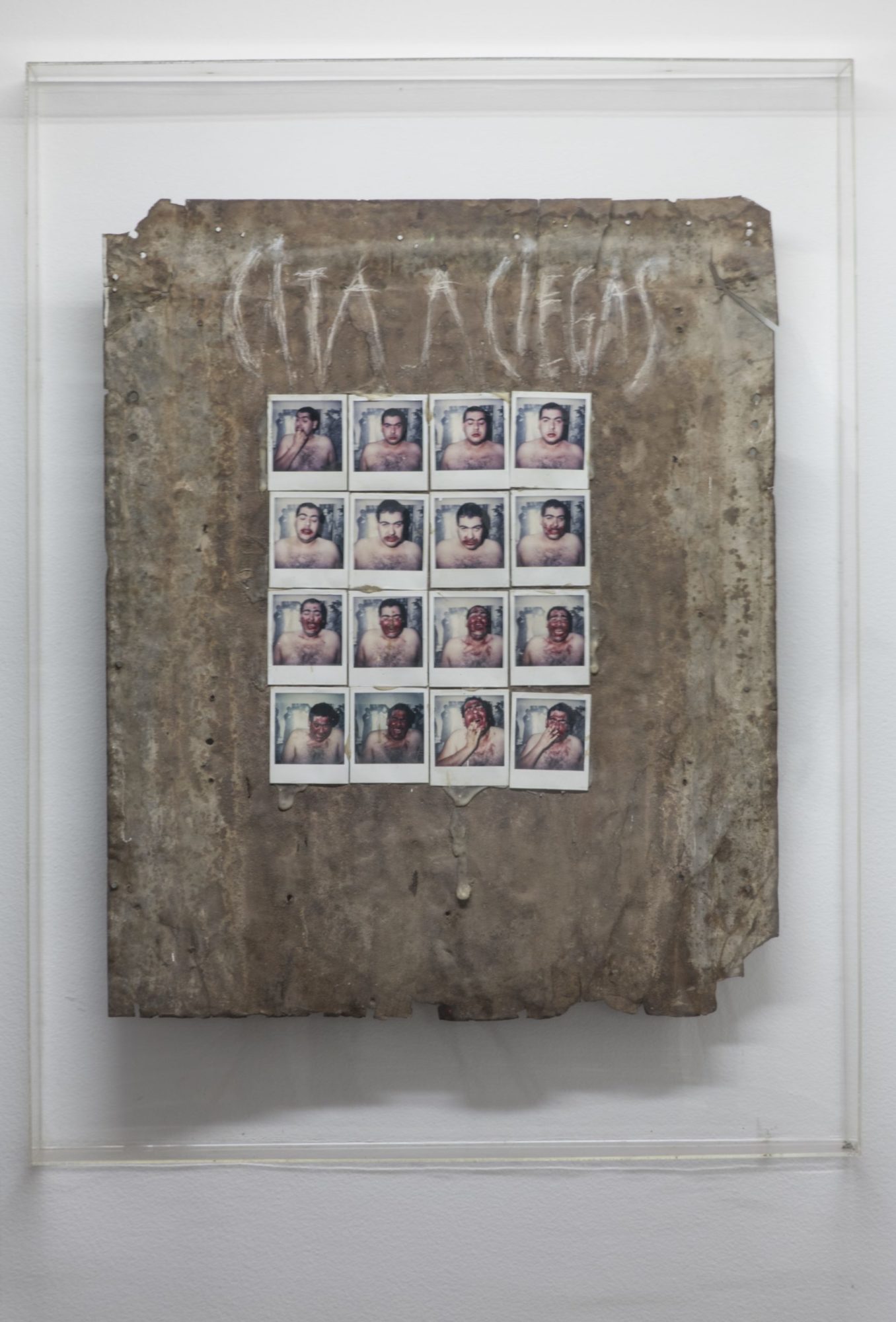

Leppe repeatedly reprised his own gendered transformation, as in the installation El objeto de la movida (Object of the movement) (1982); it included a grid of 16 sequential self-portraits in which he performs for the camera. In the first 4 images, Leppe poses stoically in bright red lipstick. The pigment expands gradually around his lips, first as a sloppy outline, and then as violent slashes of rouge across his face. As his bearing grows panicked and tormented, his feminine self-fashioning unravels into a scene of personal and political violence.

Carlos Leppe, El objeto de la movida, 1982 [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

That same year, Leppe accepted an off-record invitation to participate in the 12th Paris Biennale, where he mounted the performance piece Épreuve d’artiste (Artist’s Proof) in the men’s bathroom of the Musée d’Art Moderne. After entering the lavatory in formal attire, Leppe undressed, applied dramatic makeup, and donned a showgirl outfit complete with a tall headdress, its tricolor feathers recalling the flags of Chile and France. After assuming this theatrical alter ego, Leppe then danced to a Cuban mambo, ingested and regurgitated a slice of cake, and finally crawled from the urinals toward the halls of the museum, where he collapsed in exhaustion.

Carlos Leppe, Épreuve d’artiste, 1982, performance [photo: Carlos Leppe Archive; courtesy D21 Proyectos de Arte]

Taken in its entirety, the performance transformed the space of the men’s restroom—a site in which masculine behaviors are encoded and rehearsed—into one of metamorphosis, pageantry, expulsion, and defeat. In the process, Leppe embodied an excessive, dizzying vision of masculinity and Chileanness, subverting the expectations for how orderly bodies fit into the national narrative.

Amid decades of censorship and violence, Leppe rescripted gender and masculinity to trouble the realities of dictatorship and transgress the normative boundaries of self, citizenship, and the state. His work disentangled the many father figures that enveloped him, from the looming presence of heteropatriarchal norms to an oppressive military state and masculinist state of order. In these efforts, Leppe imagined la patria in a way more closely linked to art historian Carla Macchiavello’s reading of the feminine noun and its masculinized subject as “a curious form of linguistic transvestism.” From this symbolic point of disruption, Leppe performed a national body all his own: a Chile of inversion, fluidity, and multitudes—a cosmos of queer possibility and becoming.

Joseph Shaikewitz is an art historian, a curator, and a PhD student at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, whose research focuses on 20th-century art of the Americas and feminist, queer/cuir, and transgender theory. Originally from St. Louis, MO, Shaikewitz received an MA from Hunter College, CUNY, and a BA from Johns Hopkins University.