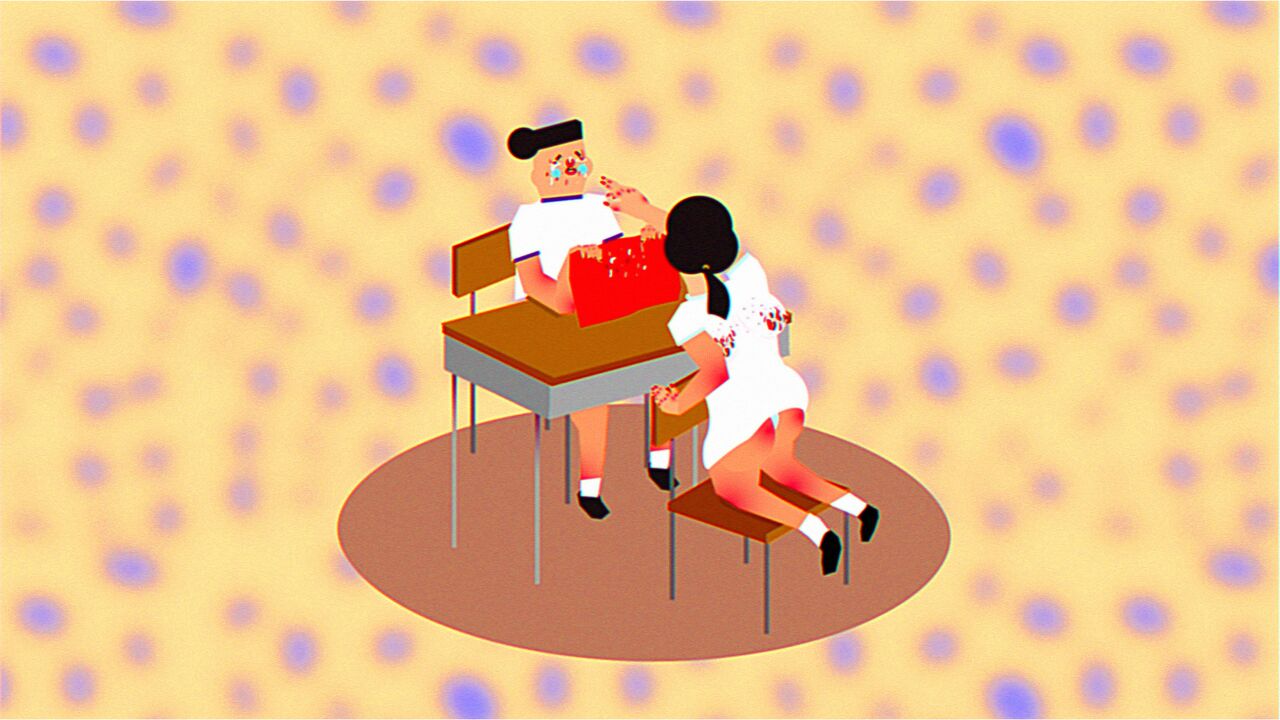

Wong Ping, stills from Jungle of Desire, 2015, single channel video animation [image courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery]

Wong Ping: Beyond the Pleasure Principle

It is impossible not to recognize Wong Ping’s work once you’ve been exposed to it — “exposed” being the operative word, given the deep perversions that infuse and narrate his distinctive animated shorts, sleek, bright, and minimally rendered in the flat style of 1980s; pixelated video games, refined for the 21st century.

Jungle of Desire (2015), for instance, is a story of an impotent man who spies on his prostitute wife. One of the chromatic animation’s opening shots shows the couple in the bedroom—husband in the closet, wife on the bed, where she smokes a cigarette and wears red lingerie. On the bedside table, there’s a picture of them on their wedding day, and in the corner of the room, a Chinese lucky cat. When Jungle of Desire was screened at Things that can happen, a nonprofit arts space in Hong Kong, in 2015, and later at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2016 with Edouard Malingue Gallery, these lucky cats were added to the video installation, their paws replaced with synthetic phalluses. As the story goes on, the male antihero—an animator, like the artist—becomes sexually obsessed with a cop who pays nothing for sex but gives his wife “the perfect orgasm.” (“I cannot tell if I am in love with the cop,” the narrator admits, “or am I identifying with him to conquer my wife.”)

“Jungle of Desire perfectly manifests my feelings about Hong Kong,” the artist told me between April and August 2017. “Look at the concrete buildings; each claustrophobic cubicle is filled with carnal desire.” The work draws on the urban context in which it was first shown: the working-class neighborhood of Sham Shui Po, known for its electronics markets and populated by sex workers. After reading an article about police exploitation of prostitutes, Wong Ping developed the film in response, animating it with archetypes—in the artist’s words, “the impotent man, the nymphomaniac prostitute, and the corrupt police officer”—who “seem to live in a primal jungle, feeding on the reciprocity of their needs.” For the artist, sex in his work could “be understood as a language and a rhetorical device, the way the Triads are used to talk about politics,” referring to Chinese mafia syndicates, “or horror films about life.” Hong Kong can be seen in the same way, too, always shown as “an elaboration” of urban space in general, and of its capacity to oppress as a “living environment.”

Desire, here and throughout Wong Ping’s work, is distilled into a form of pure and total consumption—sexual, material, biological, emotional, environmental.

Wong Ping, stills from Who’s the Daddy, 2017, single channel video animation [images courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery]

One of the artist’s first animations, and a precursor to his more recent work, was the 2010 music video for FRUITPUNCH’s “We Want More,” which clearly reveals Wong Ping’s debt to the pixelated computer games of the 1980s. Designed to emulate an arcade game, the video opens with an on-screen request to insert sperm (rather than coins) to begin; lines of men are then pictured crawling in and/or out of what looks like an 8-bit rendering of a vagina. In subsequent “worlds,” to use early Nintendo parlance, a man and woman are pushed toward each other by arrows, until a giant arrow pierces their heads together; a man collects falling academic degrees; and a line of beggars bow in front of a money man (when one of them rises up, he is beheaded). The video is an effective articulation of what feeds Wong Ping’s work in general: an idea that life is a race of endless consumption: everyone participates, but only a handful win.

Hong Kong, once described by economist Milton Friedman “as the world’s greatest experiment in laissez-faire capitalism,” is the perfect arena for such a game. The city appears throughout Wong Ping’s animations, its bauhinia flag wilting, for instance, in Emo Nose (2015), which tells the story of a solitary man whose nose learns Cantonese, grows independent, and eventually leaves him to pursue a life less isolated. In the artist’s 2011 music video for No One Remains Virgin’s “Under the Lion Crotch,” Hong Kong Island is attacked by a mechanical one-eyed beast—a “tyrannical phallic lion”—that emerges from beneath one of the area’s hills. (The animation differs in style from his later work in its color scheme—fewer acids, more pastels—and by using softer edges to move away from the 8-bit look.) Operated by two controllers, the monster encounters a quartet of individuals; two are skipping rope while wearing tank tops, one of which reads “I <3 HK,” the other, “HK <3 U.” What ensues is a massacre, in which a final survivor flees in the beast’s detached phallus-turned-rocket, and a purple “motherly figure” emerges from the sea to thwart the escape by using this vessel as a dildo and spilling blood onto the island below.

Many of his own friends left the city, and the music video was a way for him to work through his “emotional baggage”—an important process during which he struggled to find a “balance between overly self-evident storytelling and candid expression.” He wanted the video to “be an autonomous story in its own right”—it would have been meaningless, in his view, to “represent the social climate verbatim.” (“You might as well just watch the news,” he noted.) He tried not to be “too visible,” hoping his animations would mean something to viewers whether they understood them or not, “even if only as a perverse story.” These animations are abstractions illustrated by abstractions—a superposition of refined stimuli. “Life in the city destabilizes everyone’s mind and body,” the artist has explained. “To calm the mind, I can only turn to a caricature of that madness as some kind of meditation.”

Claustrophobia, in addition to solitude, is a constant leitmotif in Wong Ping’s work, expressed even more in the narratives than in the images themselves. In Stop Peeping (2014), a young man who works 16-hour days and “lives in a tiny flat in Hong Kong” reveals his obsession with the university student who lives next door, detailing how he spies on her through a hole in the wall between their apartments. When the narrator admits to his voyeurism, we see within a dark, midnight-blue frame a small white square emitting a prism of white light pixelating outwards into shades of bright shades of teal, pink, and pale blue. Two hands, one on either side, bracket this source of light, a bloodshot eye depicted on each—they seem to hover, reaching for this window into the young woman’s flat without ever touching it. On the other side of this square, the woman’s room is represented in the manner of a sleek cube à la James Turrell, its back wall a sky blue that radiates outward to become a candy pink. In front of a three-paned window at the center of the frame stands the narrator’s object of desire in her underwear, staring out at a postcard sunset—a bright orb against a fiery, gradient sky. The room is spare and cleanly rendered, as many of Wong Ping’s images are: composed as shapes on a highly formal plane, in which color contrast plays a dominant role.

Destabilizing the aesthetic balance of these subtly crafted scenes is an oppositionally crude and dense story, related in a deadpan voice. The objects contained within the woman’s minimally outfitted room include a potted plant, a floor fan decorated with billowing aqua-green tassels, and a drying rack draped with the girl’s daily running clothes. It is from this rack that our Peeping Tom secretly collects her sweat, which he freezes into popsicles he then ritualistically consumes. Desire, here and throughout Wong Ping’s work, is distilled into a form of pure and total consumption—sexual, material, biological, emotional, environmental—such that each animation functions as a mirror. “Every work is an attempt to explore multiple dimensions,” according to the artist, “always touching on a little bit of love, hate, and politics.” The white square through which Stop Peeping‘s protagonist gazes is a gesture, perhaps, towards the computer screens that have come to act as peepholes for the contemporary otaku pursuing his/her obsession online. Against the simplicity of Wong Ping’s images, then, unfolds a layered narrative composition, in which basic structures of desire are articulated and interpretable at once as metaphors and as lived facts.

Wong Ping’s stories have indeed been based in the artist’s personal truth, with a confessional tone informing each piece. When the artist graduated from Curtin University, Perth, Australia, with a degree in multimedia design, he did not feel he had mastered many skills in animation. After landing a job in post-production at a TV station before he “could even manage the basics,” he had to learn on the go. (The job involved “working through each frame to remove pimples and wires in films, enlarge female celebrities’ chests, and so on.”) On his own time, he began to write stories and create music videos, some animated, with the knowledge he did have; these projects became an emotional outlet at a time when he found himself questioning his life and work. Of that period, Wong Ping recalls that “a sense of vengeance against the world of formalities” had emerged “out of nowhere.” He developed a new routine, whereby he would come up with stories at work, animate them at home, and upload them online—a process that “proved a better catharsis than masturbation.”

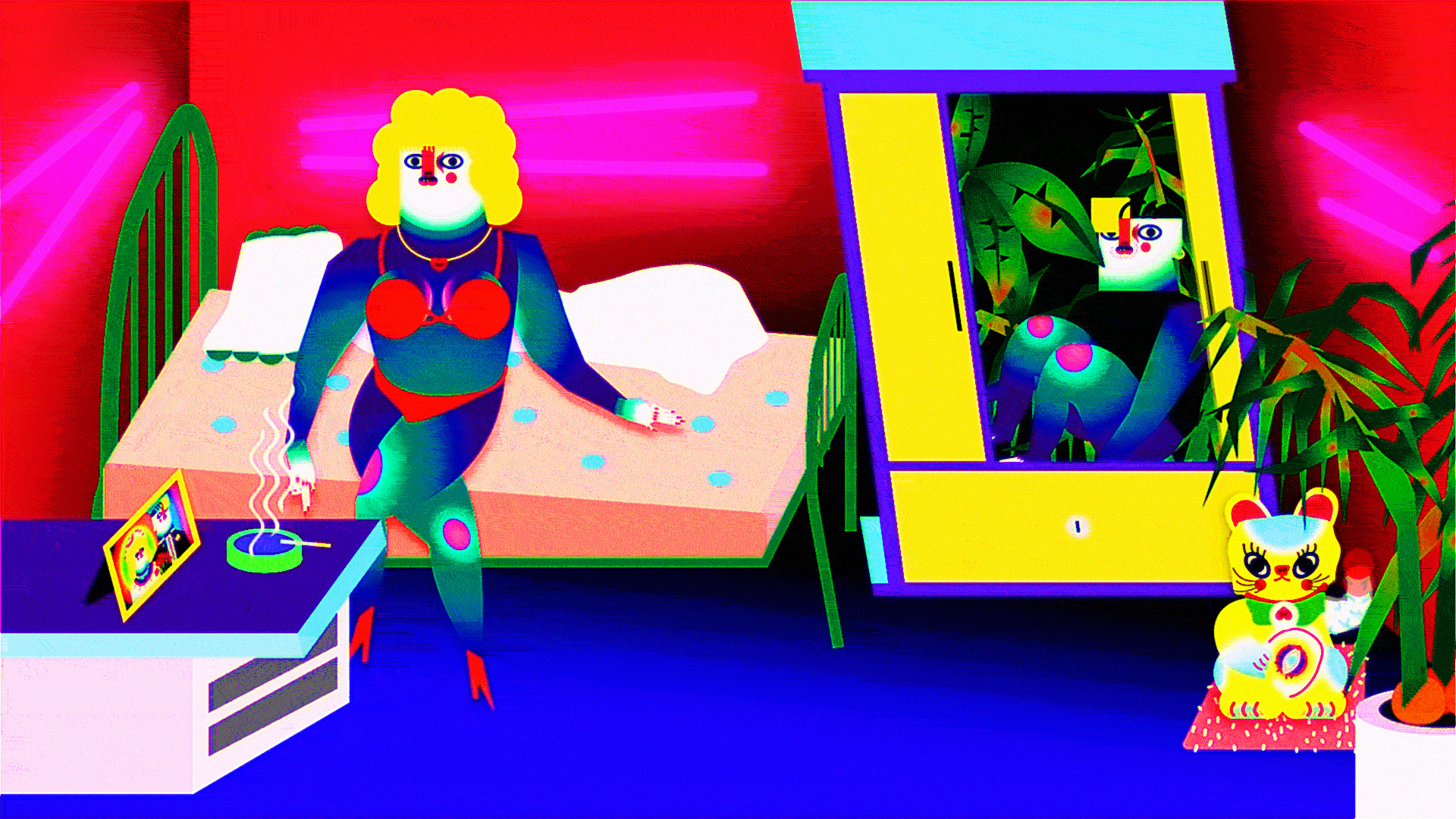

This idea of catharsis is key to understanding the depths that Wong Ping’s tales reach. In Who’s the Daddy (2017), a man begins a dysfunctional relationship with a woman he meets on a Tinder-style dating app. The affair ends catastrophically, with the woman poking out one of his eyes with a stiletto heel, and later giving him an aborted baby as penance. At no point does the narrator ever see himself as a victim, despite his rageful paramour. (She is a “conservative” like him, too: “fisting is the bottom line of our beliefs,” he says in the film.) Instead, he understands his experience through the memory of his mother, who told him to “kiss daddy passionately” when he was young—a memory of his parents he connects to his obsession with being conquered and harassed by power.

Contradictory roles and pathologies—patheticism and power, submission and dominance, hunger and satisfaction, absence and fulfillment—somehow cohere in Wong Ping’s works, presented on equal terms in his picture planes so as to complicate their reception. (In his 2015 short Doggy Love, a teenage boy bullies a classmate—a girl with breasts on her back—but his scorn yields devotion, as she teaches him how to love.) Wong Ping’s characters—and their portrayals—thus escape easy judgement.

Wong Ping, still from Doggy Love, 2015, single channel video animation [images courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery]

On his representation of women, the artist has noted: “viewers probably think my portrayals of women zoom in on their hostility and controlling ways.” In a certain sense, these women serve to highlight the misogyny and virgin/whore complexes of a prevailing patriarchal culture that, like the experience of urban life, transcends cultural and national borders. “But from the perspective of fetish,” the artist said, “these [portrayals] are actually a kind of love and pleasure.” His mother did play him a nursery song that urged children to kiss their fathers, “lest the world end,” suggesting that patriarchal servility was propagated, in his own experience, by women. Yet “ultimately,” he said, “it’s a matter of functional and purposeful implantation rather than nurture.” Here the artist’s world is a palette of contemporary allegory brimming with slow-stewed, dystopian frustration, through which personal experience connects to larger social patterns.

The Other Side (2015), a two-channel video installation created some years later as an M+ museum commission, expands on this sensitivity. The film opens with a man confessing that he wants to leave the place he is in: a space of limbo—his mother’s womb—where souls await their physical reincarnation. When the man is born, he lands in a vast red field of turnstiles, where his mother’s legs lie spread out in the position of Gustave Courbet’s 1866 Origin of the World (depicted here with less pubic hair). Finding this new place even more meaningless than the previous one, the man begins a journey to what he calls “the other side.”

Wong Ping, Jungle of Desire, 2016, installation view, NOVA sector, Art Basel Miami Beach [image courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery]

Eventually he finds another vulva, in front of which two security guards surround a glowing orb: an artwork, we are told, that is called Hymen. The man eventually begins to long for the place from which he came, and returns to his mother to attempt to re-enter the womb. Wong Ping describes the parade of genitalia in his works, as “merely the artwork’s language,” and insists that “narrative itself ” must always take “center stage.” Stripped down here is the fundamental idea of displacement, with the experience articulated in symbolic terms: through the three ages of man, with the the notion of home considered at once as a place of origin, a site of exclusion, and an organic body.

Wong Ping remembers feeling a certain pessimism while making The Other Side—a sense that there is no way of escaping the world, since it is as it is. Looking back on this work led the artist to wonder: “Isn’t my own burden what matters most?” Like the purging he claims to have felt when he began to write his stories—an ejaculating catharsis, the artist recalls—at the core of Wong Ping’s work is an impulse to make individual desires, experiences, and thoughts public, and expose them as part of a perversely relatable collective subconscious.

Such exposure is a fact of life in the digital age, which is both lived out in utter secret (in dark apartments, perhaps, and even darker psychic recesses) and broadcast into the communal (and commercial) sphere of the Internet. “From Facebook you can see the frustration we all share every day,” Wong Ping has observed, “yet we remain ambivalent about politics.” This ambivalence feeds into his films, which essentially demonstrate how we expend energy, in a world with few productive outlets to channel our vitality toward real revolution. The incomplete but deep satisfaction of the voyeur is fleeting and addictive, escalating to a certain nowhere; Wong Ping’s work allows the viewer to feel the same, uneasy release.

Stephanie Bailey is an ART PAPERS contributing editor.