With Drawn Arms: Glenn Kaino & Tommie Smith

Glenn Kaino, Bridge, 2014, fiberglass, steel, wire and gold paint. [photo: Mike Jensen, courtesy of the artist, Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago and High Museum of Art, Atlanta, © Glenn Kaino]

Share:

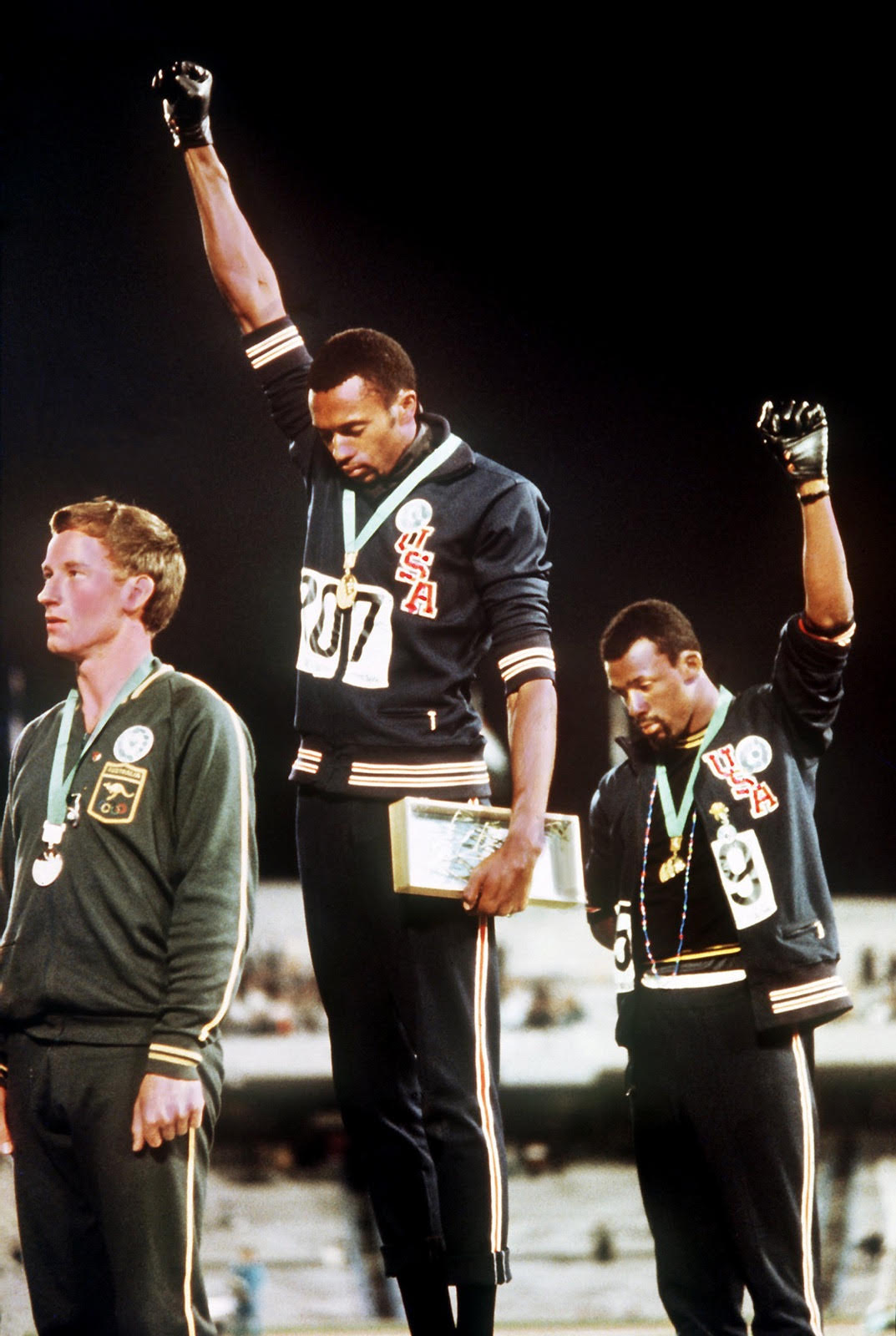

Each of us keeps images in mind that are without context or explanation. These memories and images don’t have to make sense; they’re just some things we have. Younger generations might not know the name Tommie Smith, but they may know his black-gloved fist. They probably know the image of Smith, his neck draped with an Olympic gold medal, his body elevated by the first-place podium, and his fist raised in a gesture of solidarity with people fighting for justice worldwide. It exists in our collective memory of images, like the Newsweek cover picture of a black woman holding two babies and wading through water after Hurricane Katrina, or like a picture of Eric Garner lying face down on the sidewalk. We carry these images with us—in a part of our hearts that can be desensitized, made indignant, or, in the case of Smith’s gesture, galvanized.

Smith was an advocate for change, and his silent protest greatly disrupted the status quo of the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. His raised fist caused enough of a quake to get him kicked out of the games. Images hold time at a standstill—leaving Smith’s identity suspended between that of relic and hero. In With Drawn Arms, a collaboration between Smith and the Los Angeles-based conceptual artist Glenn Kaino, the photograph of Smith’s demonstration gets expanded into an exploration of Smith’s identity, the power of Smith’s gesture, and its place in a social justice continuum. There is no question about the poignancy of Smith’s gesture in 1968. The exhibition addresses the question of its longevity, its potential to inspire today.

Through illustration, video, sculpture, printmaking, and archival objects, Kaino stretches Smith’s story like an accordion, far back into the 1960s in an attempt to touch the present moment and bridge his legacy. In an excerpt from the upcoming documentary With Drawn Arms (2018), which chronicles Smith’s life and collaborative work with Kaino, Smith says, “I know the world will be a better place.” His sentiment is sincere, but such faith is abstract and unspecific. In comparison with the gesture itself, the exhibition is no mandate for black power. Its focus on Smith’s career and legacy as an activist lacks the intense power of the salute. For this reason, the exhibition overall appears softer and more palatable than the original gesture. However, With Drawn Arms challenges the idea that Smith’s sole purpose within the fight for social justice was to have been a controversial disruption.

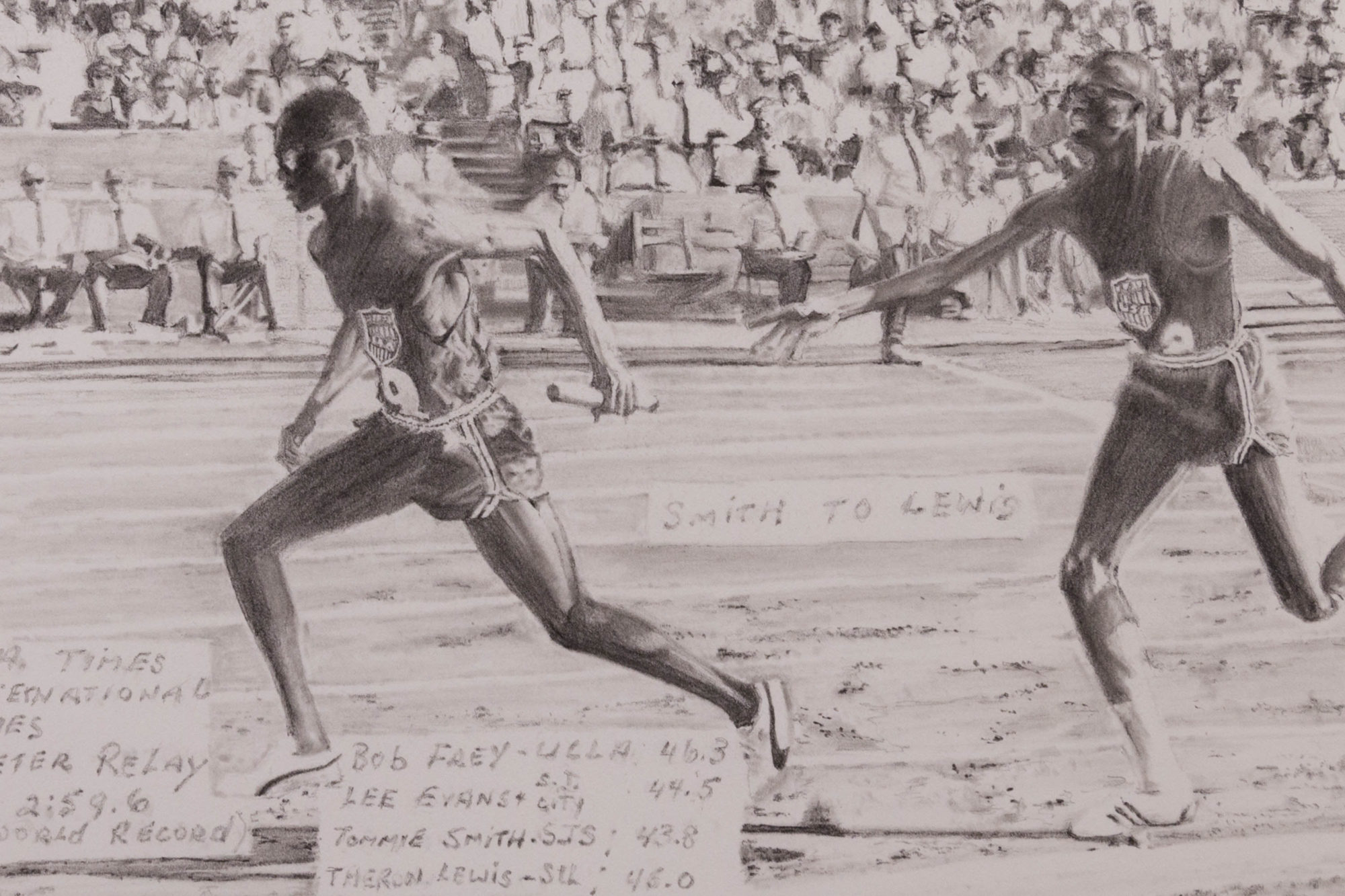

Symbols need not be specific to have a lasting effect. By sharing Smith’s history and speaking truth to power, this exhibition affirms that the significance of Smith’s gesture—beyond the disruption—has been its longevity. Kaino and Smith’s work with youth exaggerates the importance of this history. Together they held three drawing workshops at separate schools. Participants drew individual scenes from the 1968 Olympic race and learned about Smith’s silent protest. These drawings appear in the exhibition.

Tommie Smith (center) [courtesy of High Museum of Art, Atlanta, © Time & Life]

When I first entered the exhibition, I felt called by the sound of A Tribe Called Quest’s “Youthful Expression.” I quickly recognized the sampled “Inner City Blues” by Reuben Wilson, which can be traced back to the original “Inner City Blues” by Marvin Gaye, produced in 1970, the same year as Smith’s Summer Olympics. Marvin Gaye’s original track also can be heard in the film With Drawn Arms, and it firmly placed me in the context of the year all this happened. “Inner City Blues,” is sung by an indignant Gaye, fatigued by the cyclical economic repression in ghetto neighborhoods. Twenty-two years later, A Tribe Called Quest’s track sounds less heavy, and functions as a reflection of today’s youth: indignant, yet positive; depressed yet balancing the weight, socially conscious, upheld by the joy that shit like music and memes brings us. Before I experienced the exhibition, that song immediately drew a wiry timeline that bounced off itself.

Glenn Kaino, With Drawn Arms, 2018, still from single- channel video projection [courtesy of the artist and High Museum of Art, Atlanta, © Glenn Kaino]

That grounding feeling, the one I had after realizing A Tribe Called Quest sampled Reuben Wilson, was made visible in Bridge (2014), an installation on the second floor of the two-floor show. The work fills a dimly lit room with dark-painted walls more consistent with museums of a historical or anthropological focus, contextualizing Bridge as an object capable of narrating historical truth. Dozens of golden arms, modeled after Smith’s raised fist, hang from the ceiling at varying heights. Viewed over the installation’s length, the arms hang both parallel and close to each other, and they suggest a 100-foot-long bridge. The life-sized arms, all touching “skin to skin,” form a sine wave that stretches the length of the room. They represent an elongation of time and protest across generations. Bridge fluctuates like the visual presentation of a wavelength, symbolizing political movements that crest and trough.

What this exhibition draws beautifully, especially in Bridge, is the continuum of fighting, of standing up. What matters is that the continuum flows. It does not survive through the conformity of voices.

While visiting the exhibition, I eavesdropped on a docent tour for children. The docent asked them to mimic Bridge by standing shoulder to shoulder with their arms out. After this, the docent told them repetitively, “You are the future.”

Glenn Kaino, Bridge, 2014, fiberglass, steel, wire and gold paint [photo: Mike Jensen; Courtesy of the artist, Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago and High Museum of Art, Atlanta, © Glenn Kaino]

Glenn Kaino, Invisible Man: Tommie Smith, 2018, aluminum [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the artist and High Museum of Art, Atlanta, © Glenn Kaino]

When history is told through the lens of a single, highly aestheticized image, a present-day call to action is difficult. At the start of the exhibition, we see Kaino’s graphite drawings. Among the sketches is Sketch: four framed graphite photo-realistic drawings, modeled after still photographs depicting milestones in Smith’s career. In each drawing, Smith is running, seemingly completing a race. Kaino has added text to the drawings that explains of the moment shown. Although Smith is most widely remembered for the 1968 Summer Olympics, the drawings assert that these other races are also historical achievements worthy of recognition.

Kaino interjects into history again in Study for 19.83 #1–#4 (2013). Four identically sized images reproduce Newsweek’s July 15, 1968 cover. The cover is evidence of the stereotyping and demonizing that impaired Smith’s career and damaged his image. The words “THE ANGRY BLACK ATHLETE” are superimposed onto a photograph of Smith sprinting in the Summer Olympics. In each image, Kaino uses alcohol to smudge and redact different parts of the image until the words are indiscernible and fractured. I studied which words were partially erased by the stains, expecting another meaning to reveal itself in what remained, but found no deeper revelations. No matter what words Kaino effaced, Newsweek was successful in reducing Smith to a dehumanizing caricature.

Glenn Kaino, Studies for 19.83, 2013, alcohol transfer prints on paper [courtesy of the artist, Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago and High Museum of Art, Atlanta. © Glenn Kaino]

Since 1968 Smith’s iconic gesture has reverberated in the collective consciousness of people willing to fight for justice. While the slick look of the exhibition somewhat dilutes the radicalism of the black power salute, this limitation does not totally undermine the exhibition’s impact. There is that chant that goes, “Ain’t no power like the power of the people, cuz the power of the people don’t stop, say what?” I’ve screamed it before, without truly understanding why, but the lineage of Smith’s activism chronicled in With Drawn Arms resembled that chant to me. Every time a voice speaks truth to power, it earns a place in what must be a continuum of fighting. Passing down those stories to bridge time has a place, too.

The exhibition puts Smith’s actions in context with international struggle, but his protest was not just a part of the fight for human rights. It was, and remains, a historic moment in the fight for black lives.

Taylor Janay Manigoult, an Atlanta-based artist, could at this moment be contemplating which selfie to caption with Drake lyrics (written in all lowercase) to share with their lovers. They use photography and poetry to give folks a way to dream, so that we may know what it looks like to be vulnerable, loving, and free. Their work can be found on their website at taylorjanaymanigoult.com or instagram @taylrjanay.

“With Drawn Arms: Glenn Kaino & Tommie Smith” [September 29, 2018–February 3, 2019] is at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.