What do we want from each other after we have told our stories

What do we want from each other after we have told our stories?, 2020, still

Share:

I am not sure I want to write this piece.

Each word has had to be wrenched out of me. No flow, as promised by my practice as a “writer,” just vomit or bile that must be expelled but tastes nasty as it rises.

Writing is hard, it is true, but particularly, recently, as I have sat down regularly to think through how art practices (from administration, to craft, to criticism) might be more liberatory, I have struggled to see the point. How possible is it to imagine freedom when we seem so devoted to the imperialist structures of competition, exceptionalism, scarcity, and colonial “discovery”?

Repeatedly I have thought to myself, I can’t think about this anymore.

Maybe this is what Stuart Hall meant, less recently (in 2004), when he was “thinking [aloud] about thinking” and said he believed the world is fundamentally resistant to being thought. “Thus,” he expanded, “one of the perplexities about doing intellectual work is that, of course, to be any sort of intellectual is to attempt to raise one’s self-reflexiveness to the highest maximum point of intensity.”1

Recently, I hear a quote from Toni Cade Bambara repeatedly. It whispers to me online, through the words of others. It is from The Salt Eaters, a book from 1980 about the leaps of faith inherent in our searches for freedom and healing: “Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well? … Just so’s you’re sure, sweetheart, and ready to be healed, cause wholeness is no trifling matter. A lot of weight when you’re well.”2

I often return to the pain of thinking, and the truth of our collective (and seemingly consistent) ambivalence to healing, recently, when I write. These are thoughts that seem to eat each other, make the text disappear as I type. The world resisting my thoughts.

Perhaps the only form of criticism about cultural production that might feel reparative is one that is broken into pieces.

This Work isn’t For Us

It’s been two years since I completed my research on institutional racism in the UK arts sector, This Work isn’t For Us. The title that seems like a slogan or a chant is often assumed to be an argument for opting out. But actually, it was about what became obvious when you stayed.

bell hooks said she came to theory because she was hurting. And I, too, came to it for healing. For the power to name the things that cause pain, for the wholeness evoked by the hope that that naming might dislodge that hurt. But in a world that isn’t collectively free—and doesn’t want to be—the privilege to theorize that which causes harm is often undertaken with a respectful distance from its locus. Sometimes, in that naming from a distance, things are lost.

This Work isn’t For Us theorizes my embodied collisions with “recently,” case study, data, and lived experience. It moves back and forth between these axes. It is nomadic and wandering, trying to gather meaning and find resonances—from culture, from film, from music, from the news, and from government. Perhaps, in academic terms, this “recently” might be “disciplined” as describing a “conjuncture,” but for me it was a kaleidoscope, mixing layers of affect that reoriented themselves to present new meanings every time I returned to the research.

The written parts of the research fell out of me, words fleshy and softly formed, finding their shape on theory written differently, with different intentions, less recent pain. At the time, I felt that the body of the writing was held in place by the work of critics who saw things that I didn’t. I relied on the stability of such texts to lend me their authority, because my experience of working in the cultural sector gave me none. I was too close, my pain too fresh.

Or my hands too unclean.

Some of these sources make, and underline, the division between managers and artists, and weaponize borders between the political and apolitical, comrade and opponent, the devotee and the sellout. In practice, these boundaries don’t hold. They are constantly shifting, unstable, unreliable.

The Night Nurse

Recently I’ve been dreaming a lot about a night nurse.

About 10 years ago I was in hospital and in unbearable pain. I wailed for what felt like hours, hit my buzzer, and a nurse slowly came to give me painkillers, which did little. I called her again, and she told me to be quiet, to stop making a fuss, to be grateful that she had walked from one end of the ward to the other to get me the medication I asked for. Vulnerable and alone, I felt betrayed by her, and asked her why she was so cruel. She looked affronted, surprised at my reading of her.

Recently, her face returns to me. What structure emptied her of care?

I think about my friends who recognize themselves in This Work isn’t For Us. A few of them (not many) have senior positions in the arts. They are some of the best people I know. I see, at times, the ways they must discipline that care, or else their bodies do it for them. The times when they stop answering calls because they are burnt out. Or when they freeze in meetings as uncomfortable issues are raised, because there is no support to process their valid, embodied responses. Or the times when the soft, emotional being that I know must become a hardened and professional presence. I see them as I see past, present, and perhaps future versions of myself.

More recently, as I have taken a distance from the institution, I hear how they are described. They are institutional if they are perceived to not linger on discomfort. They are “lovely” if they overextend themselves and always smile, absorbing the blows of inhumane institutional process. In other conversations, all art workers are flattened into a single force—a managerial class. The managerial class is entitled; it is comfortable with the rate of “change” energized by upticks in “discourse” and believes in the pioneering logic of linear progress, representation, inclusion. The arts are full of them. I have worked for many. Me Too.

But recently, I wonder about how to untether from this label, “managerial,” those who are attempting the most radical reform in the arts—to reveal the affective labor that must be done in secret, after hours, unwatered and unnourished.

Colonial Administration

My friend Teresa Cisneros writes about her roles as a curator, project manager, administrator, and sometime artist as “unveiling, again and again, personal colonial acts by individuals, including myself.”3

Recently I wonder, what is the phenomenology of such colonial administration? How does it land and get processed by the body, and between bodies? Teresa describes such colonial administration as:

The practice of administering and organizing people, institutions and places of work, which maintain and replicate formats including structures, hierarchies and forms of control inherited from Britain’s colonial empire …. In many ways, how we practice the institution is part of this legacy. It can be found in how we govern institutions; from how policies are made to how power is distributed within institutions.

But what happens when we look at what these legacies have left us? Competition, hierarchy, myths of exceptionalism. Will we really want to give them up? Or will we still make sure to thank the institution in our speeches, ask who won the prize, feel like we’ve made it if we’re “included” in their program, festival, or show?4

In This Work isn’t For Us, I tried to write about why I ended up doing work that I hated, working with people who had little respect for me and my perspectives, but told me I was hired for those perspectives, then withheld skills, promotions, salary increases while giving them freely to others.

Why didn’t I want to be free?

I wrote about my grandfather’s efforts to have my father be born a British subject, making sure his wife gave birth not in “liberated” India, but in occupied Aden. My grandfather exchanged freedom for “progression.” For this exchange, my father received a British passport marked with his birthplace (now Yemen). Every time he shows that document, when the border force pulls him aside for lengthy questioning about his ties to terrorist organizations, I wonder if that passport feels like the prize his father thought it was.

An embodied understanding of artworld fuckery

The role of the artist in the revolution is to look around and see what needs doing. Pick up a weapon like everyone else, run

—Lola Olufemi5

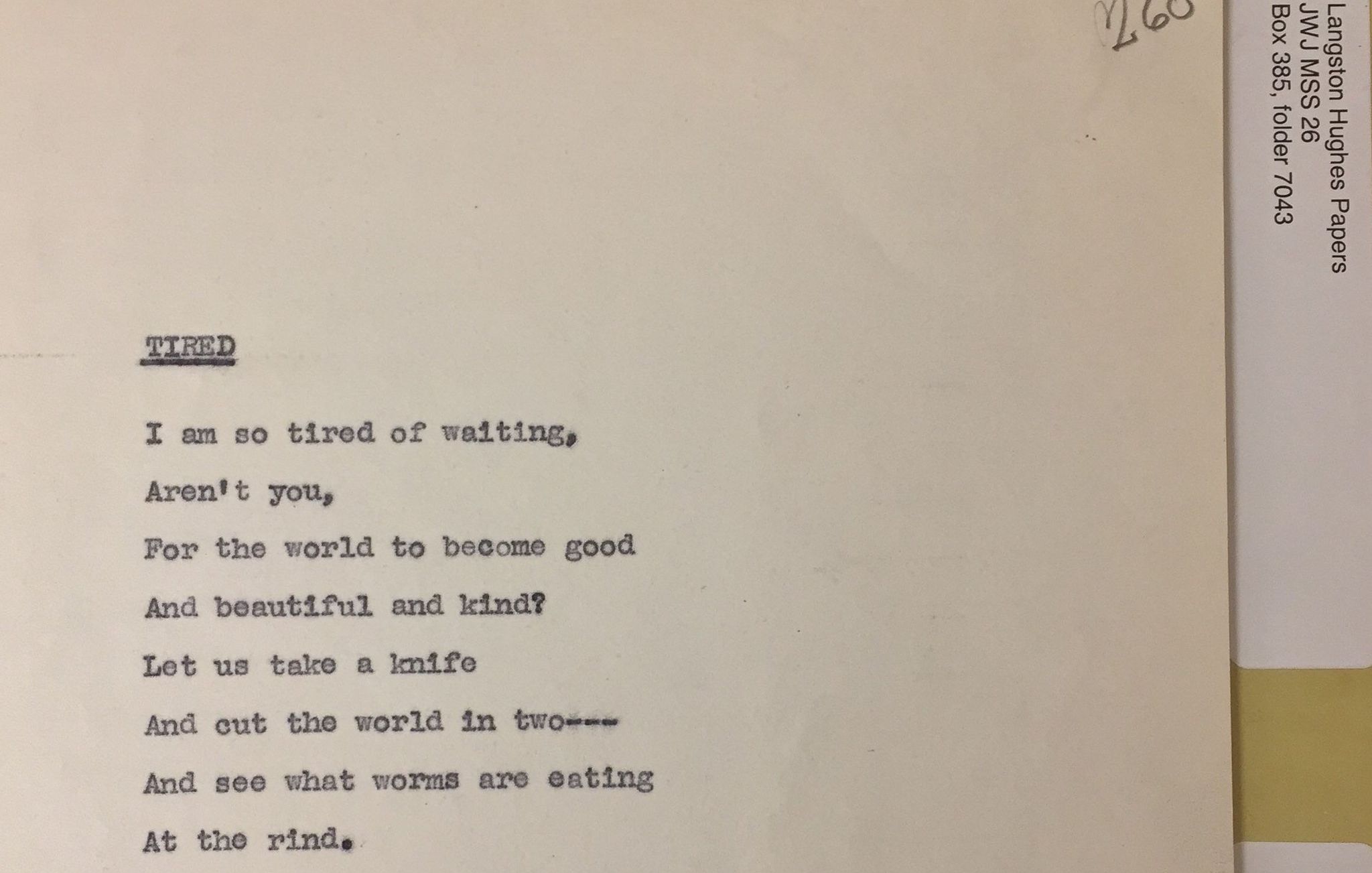

Langston Hughes, Tired, 1931, Langston Hughes Papers [courtesy of James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University]

Recently, I wonder how to write about those (of us) who enter the space of the arts sector/film industry/ARTWORLD™ with hope and desire, and are met with so little care.

These same people distribute the visibility that supports artists in institutions whose only currency is spectacle. They must exhibit with and about care, and care care care as if care were an ever-present commodity and not a finite resource that requires replenishing. They are present as a barrier, metabolizing the imperial structures of our colonial cultural institutions and providing, often through genuine care and genuine politics, the possibility of political commitment through making, showing, and engaging art.

They are the people whose practice is to actualize radical programs in places hostile to freedom, extend invitations, sometimes pay money out of their own pockets as a buffer to institutional finance processes. Their hope is remarkable—and constantly tested as it meets with the real engine of power: senior management and the board-level drip-feed of (in)attention to issues of “diversity,” “inclusion,” “anti-racism,” through endless procedure, performative alliances, and insatiable demand for “engagement” and “audiences.”

It is often the job of the conflicted administrator to sustain the pressure. A pressure that builds and eventually finds expression in burnout, exits, resignations, or desires to retrain.

And I want to talk about desire, because it is important, as it is desire that leads us to these places.

And we have to examine those desires, and these desires resist thinking.

In Lots of Shiny Junk at the Art Dump: The Sick and Unwilling Curator, writers

Lina Džuverović and Irene Revell describe the effect of the particular desires that transfix us in the arts. The essay is about the role of the curator, willing to overextend, to look as shiny as the work that they “effortlessly” bring together. But it could easily be the film programmer, the theater producer, the funding agency administrator. The text evocatively lays out the desires that lead us to these roles and asks what happens when the desire to continue to belong wanes, when we are tired and start to see more clearly “what worms are eating / At the rind.”6

The authors evoke the costs of numbing—and subsequently awakening—the very thing that gave us the energy to enter our fields, the physical and affective functions of the body:

It may take your body’s own revolt—by way of a lifelong auto-immune condition, for instance, that suddenly flares up more seriously and more chronically; or a series of years caring for the body of another …. to produce the physical barrier to this way of working that yields a more embodied understanding of this general artworld fuckery.7

As long as we are able-bodied, we can tell ourselves that our energy is put to the use of an abundance of relationship of care. From a perspective within the ongoing global pandemic, it becomes clear how able-bodied supremacy makes a commodity of anyone in the arts with a healthy body and an abundance of “energy.” It also dictates who can gain the most pleasure—and profit—from it. Who but those least affected by the grief, risk of illness, and financial worries of the pandemic are making, watching, and engaging most fully with pre-pandemic levels of cultural spectacle at this moment?

From this viewpoint, staying in our bodies and refusing to be emptied to the point of burnout is not just an issue of personal bodily autonomy, or a public health issue, but, as Mia Mingus teaches us, a political position. A position of solidarity against a system of able-bodied supremacy.8

As we spread ourselves thin across an endless array of opportunities for things to change and shift, the colonial legacy of urgency culture tells us that there is a small window closing, which we desperately must jam open. Perhaps it is true that we must use the window. But must we exhaust ourselves to jam it open? Or should we refuse its frame of polite stasis and bordered gatekeeping to escape through its light? Like Lola says: “Pick up a weapon like everyone else, run”?

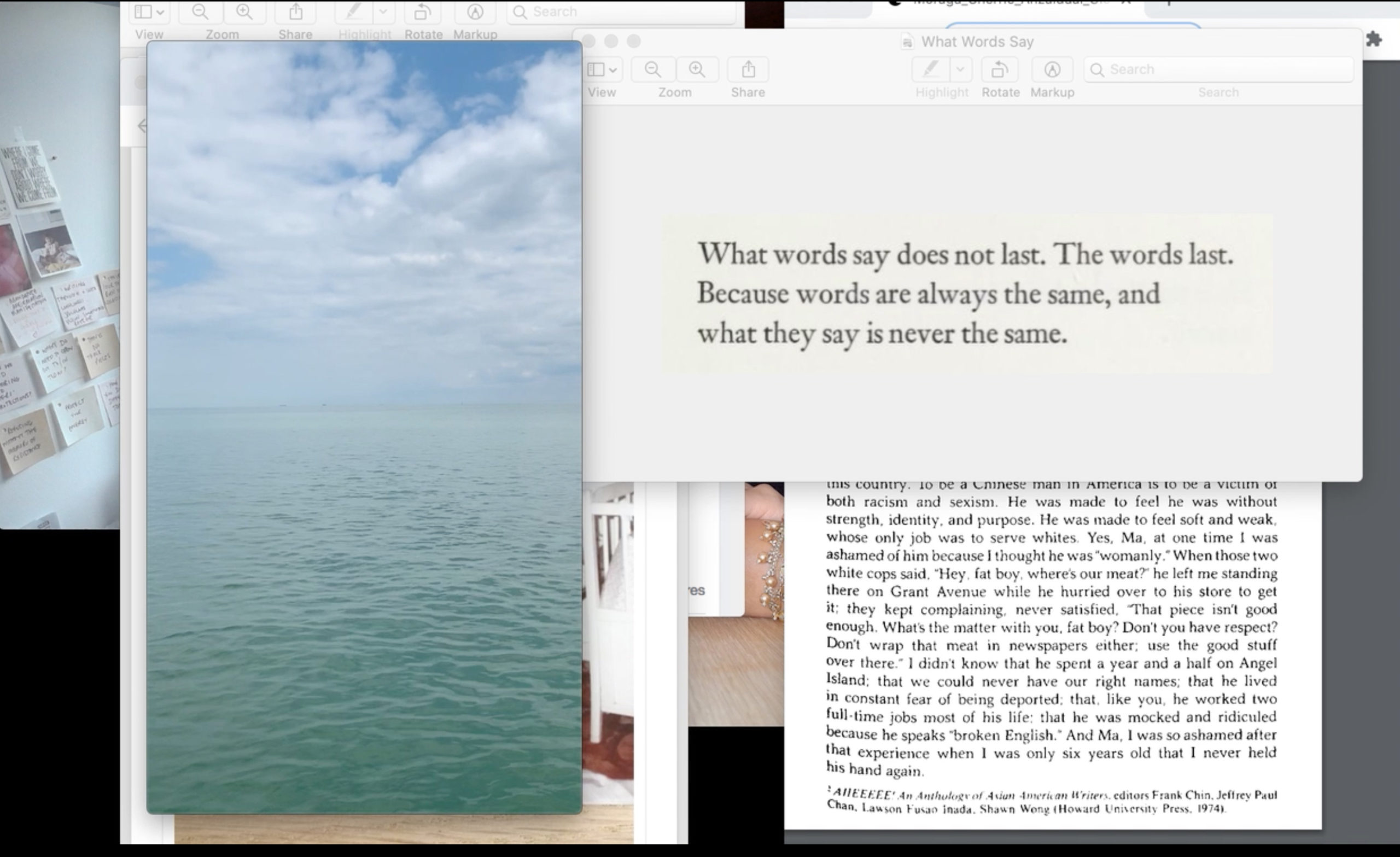

What do we want from each other

after we have told our stories?

What do we want from each other after we have told our stories?, 2020, still

Recently I revisit the last element of This Work isn’t For Us, a video titled What do we want from each other after we have told our stories?, named after lines in Audre Lorde’s poem “There Are No Honest Poems About Dead Women.” Published in 1986, the poem tries to think a thought that didn’t want to be thought.

To what extent was the 1960s Women’s Liberation Movement’s maxim “the personal is political” emptied of its meaning through an intensity of cultural production? I ask myself that same question in the video. How had I emptied the meaning of the ideas and intention of This Work isn’t For Us by performing it in public?

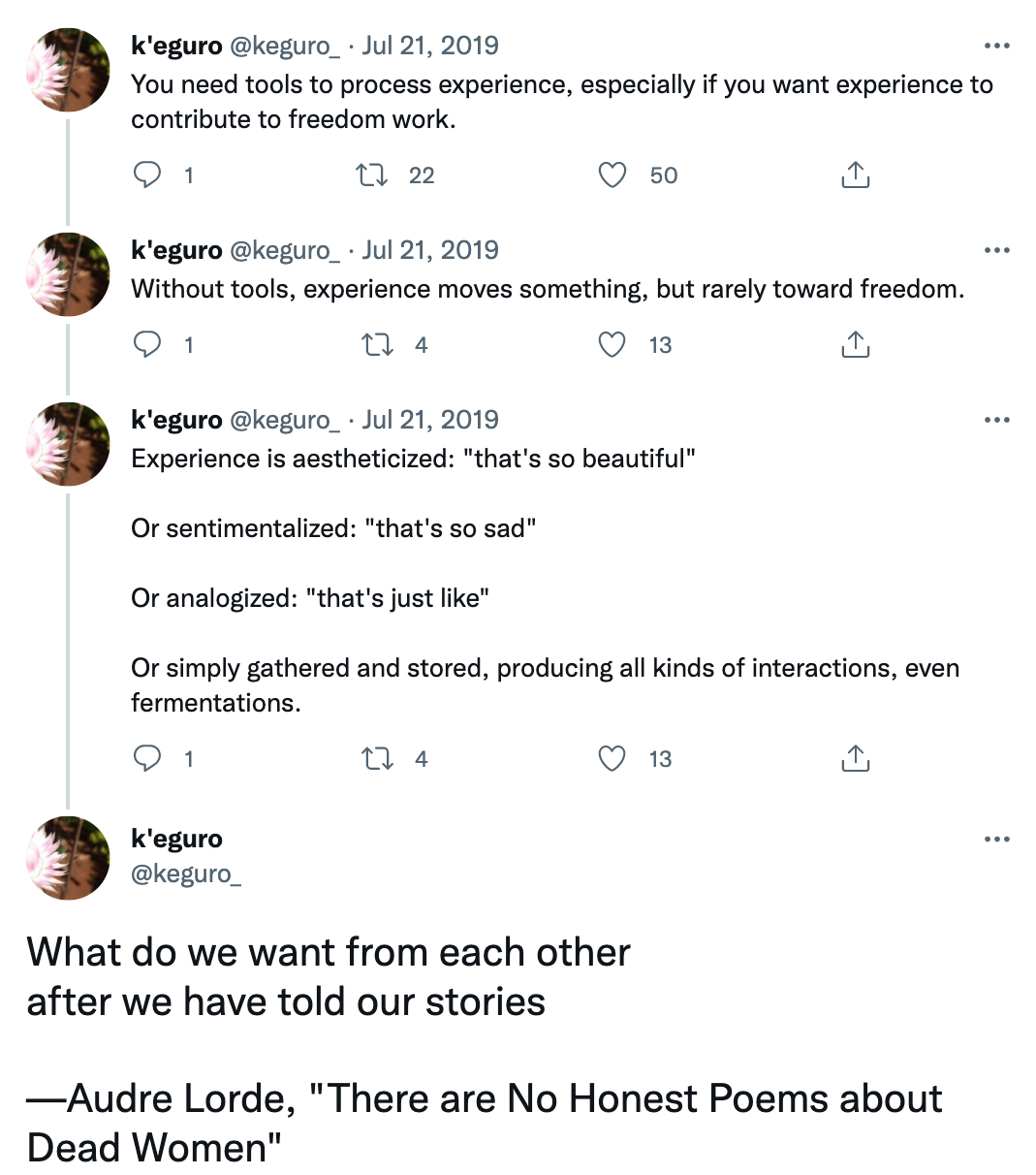

When I try to write this text, I type What do we want from each other after we have told our stories into a Twitter search, click the button “people you follow.” Right under my own tweet about the video, I see a thread, from July 2019, from Keguro Macharia:

Keguro Macharia, 2019, screenshot

It makes me think about last summer, when I attended a grief retreat led by artists and embodiment researchers Camille Barton and Farzana Khan, whose practices are committed to defending the liberatory aspects of art making, by attending to the body rather than numbing it. Barton founded a new temporary master’s program at the Sandberg Institute (2021–2023) named Ecologies of Transformation, which explores how embodiment and art making can facilitate social change. Khan, who is also the executive director and co-founder of Healing Justice London, recently co-produced an anthology, research report, and guidebook honoring 10 years of collective work on Shake!, a youth-led initiative that brought together young people, artists, and campaigners to develop creative responses to social injustice, partly by teaching such practices as grounding, taking up space in hostile colonial institutions, and finding one’s own political voice.

During the grief retreat, 15 artists, facilitators, movement organizers, and art workers—most with recent ancestral histories of migration or colonization—gathered to spend a rainy week regulating our nervous systems, shedding our hyper vigilance and states of constant activation, wrapping our bodies in blankets, and eating food cooked by artist Raju Rage. The menu was lovingly designed to care for our guts so they could easily process our food, just as we processed our undigested grief. The retreat was rooted in a belief that, as A. Sivananadan would have it, the “personal is not political but the political is personal … changing society and changing oneself is a continuum of the same commitment—else nothing gets changed.”9 Here, for the first time, I learned what the difference between activation and peace means, the bodily difference between the fight and the taste of freedom.

At one point, someone talked about the possibility of taking a neutral position to trauma when so much of the work we do relies on our identities as traumatized, unhealed, and activated.

What hope is there for healing in an art sector defined by racial capitalism? Where the etymological and administrative entanglements of “know, own and owe”10 carry histories of violence, oppression, and unpayable debt? What use is it to convince cultural institutions’ senior managers of their racism or privilege through workshops and training, to share our experiences with them, when cultural production, representation politics, and the spectacle of change garners profit precisely because of the intractability of able-bodied white supremacy in all our state sanctioned structures—including the ones into which we gather our knowledge, gather our work, gather our funds, and gather our people?

Feeling otherwise 11

I take unfeeling not simply as negative feelings or the absence of feelings, but as that which cannot be recognized as feeling—the negation of feeling itself …. unfeeling as an index of the under acknowledged spectrum of dissonance and dissent that critiques the demands of sympathetic recognition shaped by sentimentalism, questioning the liberal project of inclusion.

—Xine Yao, Disaffected: The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America

As I looked through This Work isn’t For Us in community with others during the summer of 2020, I learned about the difference in the arts between reform and abolition. These worlds became tethered as cultural institutions clamored to show that they took the grief and pain spilling into the streets during a global pandemic seriously, that it meant something to them emotionally. As many wrote statements in support, expressing pain, shame, and commitments to change, they emptied that grief of meaning, processed it into policy, numbers, data, and formed committees. Their professed will to “change,” to “feel,” met with their restrictive methods, refined over years of colonial administration, methods that keep them functioning exactly as they were intended.

Despite small gestures of institutional tinkering, and proffers of conditional access, in this misalignment of response to Black Lives Matter lies a perfect articulation of the futility of attempts for collective, liberatory change through the liberal project of inclusion.

A thought came easily during this time, which clarified without resistance: that for those of us who have been healed by theory, by art, or who believe in its possibility to do something, abolition offers a possibility to bypass what feels entrenched and makes us feel helpless, toward a new set of structures, interdependencies, and commitments that might nurture our care and not empty us (and our art) of it.

Recently, I want to say abolition quietly, so as not to empty it of meaning.

It is more than the opposite of what we have. It is—but it is more than—the opposite of cosmetic changes that keep structures in place. It explodes beyond even the utopia of collective hope as an antidote to cynicism or individualized “unfeeling.”

Its distension resists a full, delineated thought, so I offer you still-forming fragments.

I don’t mean to extract from abolition to reinvigorate a tired argument about institutional critique. I offer it as, to paraphrase my friend Lola Olufemi, a necessary inflation of the material.12 I thought the material could be inflated through more narrative, more description, but abolition offers us something else.

It is a way to think a thought that doesn’t want to be thought, to reclaim something that had been taken from me (us)—the point of it all, the pleasure of it, the desire, the belonging. A method not just to do, but to “feel otherwise.”13

In Dylan Rodríguez’s formulation, it is a praxis of human being, “a practice, an analytical method, a present-tense visioning, an infrastructure in the making, a creative project, a performance, a counter war, an ideological struggle, a pedagogy and curriculum.”14 It politicizes my refrain of “recently,” collapsing time, taking structurally enabled, historically consistent, embodied grief and pain beyond sentimentality and performed “empathy.” It honors the repetition of trauma, the repetition of its articulation, by taking love, grief, and pain politically seriously.

For many who stood for Black lives in summer 2020, understanding what the practices of abolition require from us, in our different roles, is a thought that might resist thinking. But it is a thought that deserves the commitment of our attempts.

Jemma Desai is based in London. Her practice engages with film programming through research, writing, and performance. She is currently undertaking a practice-based PhD on practices of freedom in the arts.

References

| ↑1 | Stuart Hall, Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora, (Durham, NC:Duke UniversityPress, 2019), emphasis mine. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Toni Cade Bambara, The Salt Eaters (London: Penguin Classics, 2021 [1980]). |

| ↑3 | Teresa Cisneros, Document 0 (London: agency for agency, 2018). |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | Lola Olufemi, Experiments in Imagining Otherwise (London: Hajar Press, 2021). |

| ↑6 | Langston Hughes, “Tired” (1931), from the Langston Hughes Papers, James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. |

| ↑7 | Lina Džuverović and Irene Revell, “Lots of Shiny Junk at the Art Dump: The Sick and Unwilling Curator,” PARSE9 (Spring 2019). |

| ↑8 | Mia Mingus, “You Are Not Entitled To Our Deaths: COVID, Abled Supremacy & Interdependence,” Leaving Evidence, January 16, 2022. |

| ↑9 | Ambalavaner Sivanandan, “RAT and the Degradation of Black Struggle, ” Race & Class 26, no. 4 (April 1, 1985) in Communities of Resistance: Writings on Black Struggles for Socialism (NewYork: Verso, 2019). |

| ↑10 | I owe this insight to Fred Moten, who spoke about the etymological entanglements of “know, own, and owe” in an online session at Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities titled “On collaboration within practice research” on November 10, 2021. |

| ↑11 | Xine Yao, Disaffected: The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022). |

| ↑12 | Olufemi, Experiments in Imagining Otherwise. |

| ↑13 | Xine Yao theorizes feeling otherwise as an antisocial affect, form of dissent, and mode of care. Yao suggests that unfeeling can serve as a contemporary political strategy for people of color to survive in the face of continuing racism and White fragility. |

| ↑14 | Dylan Rodríguez, “Abolition as Praxis of Human Being: A Foreword,” Harvard Law Review 132, no.6 (2019). |