Trojan Horses

Giovanni di Paolo, Paradiso 34, 1444-50 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, and British Library]

Share:

The past year, when everyone was cooped up behind screens, brought a peculiar kind of financialized culture into the mainstream, though its germs have been growing for decades. We started by calling it “social media,” then we called it the “attention economy.” More recently, it mutated into something called “platform capitalism,” while others call it “surveillance capitalism.” Astute observers such as McKenzie Wark called it, years ago, by coining the phrase “vectoralist class,” those gatekeepers and rent-seekers of information flows. It was an economic passage by which technology companies, born in a de-industrialized, increasingly online society, competed to turn sociality into data and data into financial capital—until a handful of corporations had captured all the social affect, all the data and all the capital. It was another expansion of the power of finance to liquidate all worldly relations, material or otherwise, as fungible assets subject to speculative returns. We were warned, after all: There was the antiglobalization movement of the late 1990s, and the Occupy Wall Street movement after the crisis of 2007–2008. By now, in the third year of the Great Pandemic, a seemingly inescapable financial realism has taken hold, as if it were the air and the water.

Cliff, Swirling schools of Anchovies, 2012 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, and Flickr]

At once not purely technical, cultural, affective, or economic, this shift is hard to pin down but easy enough to observe. The GameStop saga of early 2021 is part of its canon. A community of traders associated with a popular Reddit forum called r/wallstreetbets triggered a 2000% stock price surge in the flagging video game retailer GameStop, resulting in a “short squeeze” that crippled the hedge funds which had bet on the franchise’s demise. Driven by both trollish greed and righteous rebellion, wallstreetbets fomented a bait ball of self-fulling prophecy, boosted by the popularity of such trading apps as Robinhood (of course, theories abound as to whether the strings were being pulled from elsewhere). In the financial markets, amateur traders are traditionally treated as background noise, mindless extras in a world “run” by professional investors with vastly superior knowledge and capabilities. As a kind of peasant’s revolt, wallstreetbets was galvanized by more than the mere prospect of financial gain—after all, most of its participants lost their money as the stock eventually plummeted. Their avatar was the vengeful underdog who succeeded at spooking its financial masters. In the crash that followed, one viral post by a user called “Space-peanut” reflected upon the devastating impact the 2008 financial crisis had on their family: “Taking money from me won’t hurt me, because I don’t value it at all. I’ll burn it down just to spite them. This is for you, Dad.”

GameStop led to an instance of what you might call “avatar politics,” moments of popular effervescence made possible by social media’s daily cycles of intrigue and outrage.

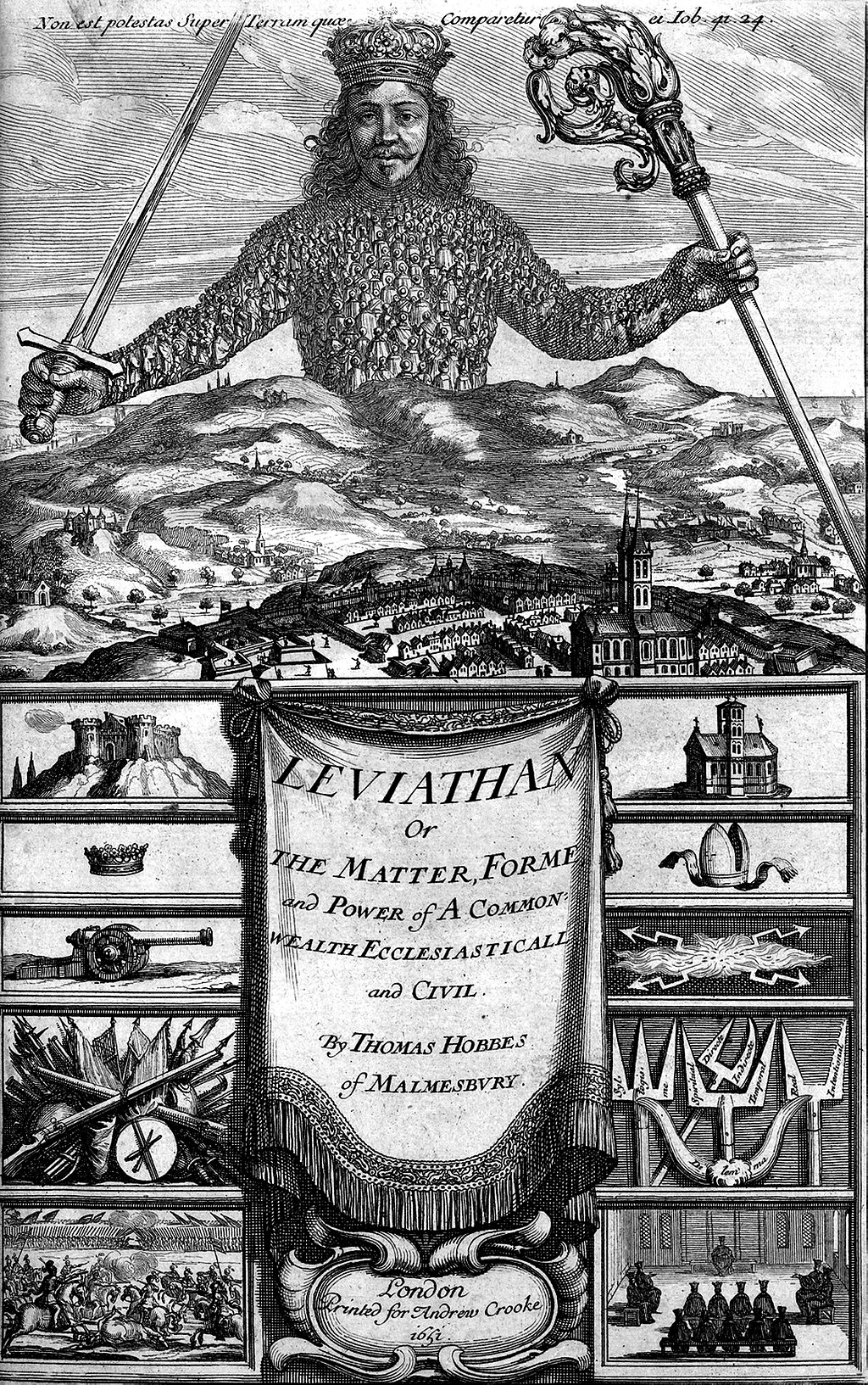

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Whether around a fandom, a conspiracy theory, a political cause, or a campaign to cancel or defund, a transient subculture forms into a leviathan determined to bend the flows of attention, discourse, and capital. Speculation, after all, is a two-way street: Just as investors seek to speculate on and influence beliefs and desires of the collective, investees (that is, everyone) also become brutally aware of their own status as latent assets, elementary particles in the memetic circuitry of social and financial capital. Of course, these strategies are symbiotic with the economics of platform capitalism, in which collective desire and the power to marshal it are always, already, a vector of investment. Whether through direct engagements with financial capital (as with GameStop), or through the swarmlike interventions of activist fandoms as diverse as BTS’ ARMY or Kamala Harris’ KHive, these stan cultures (and the avatars they coalesce) can be formidable players in a game of collective manifestations.

In a certain sense, just as trade unions gather leverage by forming cartels over the price of labor, these avatars engage in what the philosopher Michel Feher calls “counter-speculation,” realizing their potential as both assets and risks to the platform economy as a way of making collective demands of their creditors. Like a crossbreed of social media influencers, activist investors, and political movements, avatars play a powerful role in shaping the political economy of reputation, representation, and vibe. Unlike trade unions, however, their solidarity emerges not through the sustained material conditions of labor and class struggle, but rather through more ephemeral and capricious emotional forces of adulation, resentment, and wrath. Like whales breaching the water, most of them submerge as quickly as they rise. Ones that sustain momentum typically congeal their curiosity and kinship around a densely woven body of communal lore, such as QAnon.

Steve Dunleavy, Big Eye Scad, 2010 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, and Flickr]

The recent popularization of cryptocurrencies, Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), and NFTs has epitomized the cultural logics of the new financial realism. For a generation with no access to property ownership, functional infrastructure, or the promissory glow of a utopian digital sphere enjoyed by their parents, crypto culture is defined by dispossession and largely built in the image of post-millennial American trauma. As the media scholar Christian McCrea notes, “A thirst for reclaiming ownership in a world that doesn’t let you own anything shouldn’t be underestimated.” To this sensibility, the infrastructures of “Web3” serve as pathways toward less authoritarian, more anarchically co-operative forms of capitalism. As digital avatars of financial collectivity, DAOs combine fandoms, corporations, brands, and venture funds, held together by the collective ownership of digital assets, often with significant financial power. So far, their most eye-catching encounters with the “real” world have been through “financial flash mobs” not unlike that of the GameStop saga. Examples include ConstitutionDAO, which unsuccessfully tried to buy the US Constitution, and KlimaDAO, an effort to turn carbon offsets into digital assets and, thereby, raise the market price of carbon.

Giovanni di Paolo, Paradiso 34, 1444-50 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, and British Library]

While financialization permeates culture, avatar politics remind us that speculation goes both ways: Powerful forces remain at work in the crowd. It remains to be seen whether a “politics” driven by the sporadic alignments of desire, interest, and affect can be mobilized toward genuinely collective ends. For example, could a DAO take on the role of an activist investor, buy a controlling stake in an oil company, and liquidate its assets? Avatars could be a trojan horse for new models of cooperative agency in a fragmented and financialized digital sphere. But what happens if we get stuck in the trojan horse?

Gary Zhexi Zhang is an artist and writer, based in London, who works on paradigms emerging in finance and ecology, and on the web. His recent solo exhibition, Cycle 25, documented imaginary nations and cosmic economies.