Trauma and Repetition: fence by Staibdance

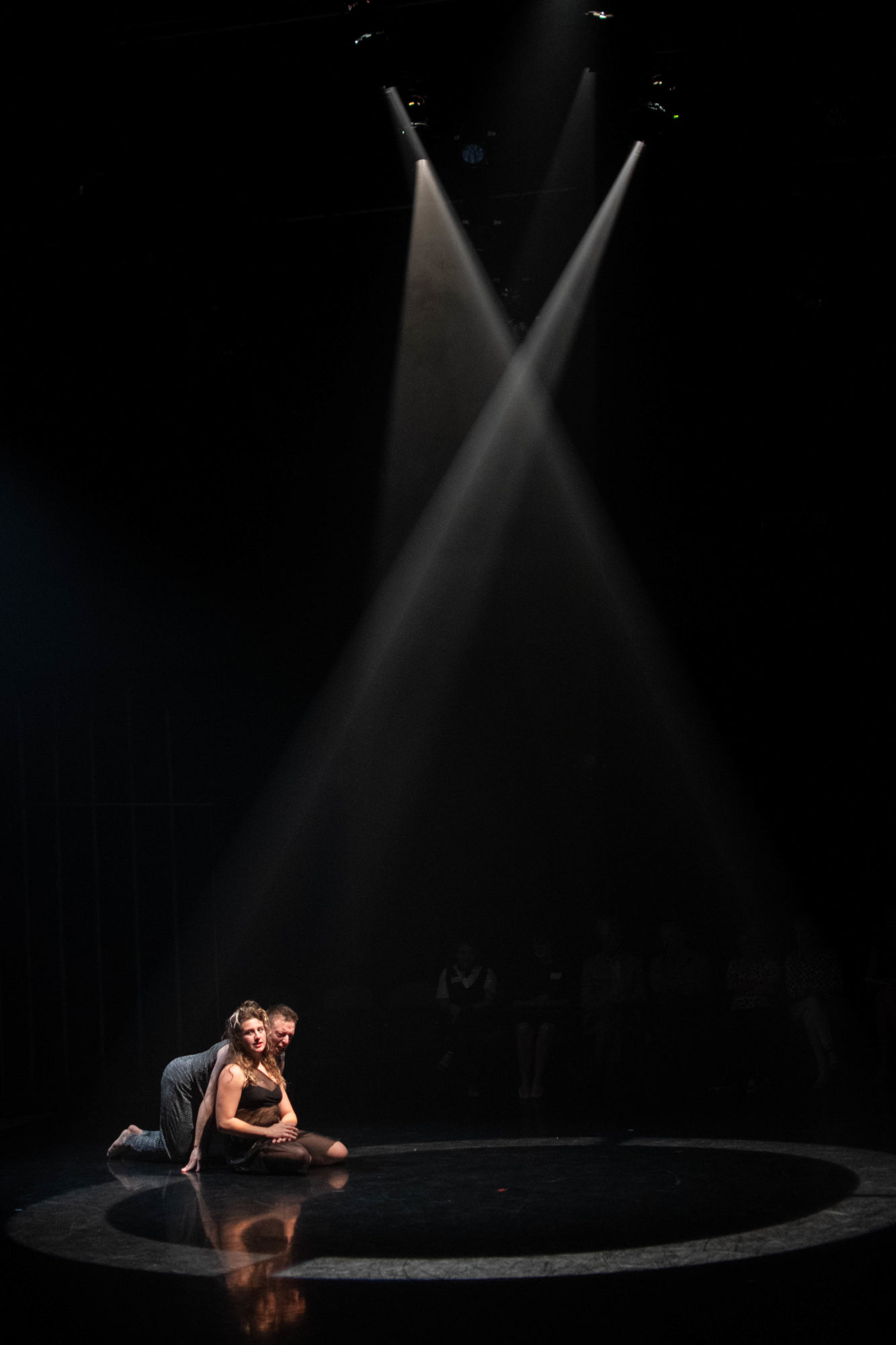

fence, performance view, 2019 [photo:© Christina Massad]

Share:

On October 3, 2019, Staibdance premiered a new work, fence, by Artistic Director George Staib in collaboration with Managing Director Sarah Hillmer and company dancers. They performed for a relatively small audience in the intimate black box performance space of the Dance Studio at Emory University’s Schwartz Center for Performing Arts. In the program notes, Staib describes fence as an exploration of the “cyclical repetition of power struggles where pivotal and meaningful histories are dismissed.” Inspired by events from Staib’s life, including the 1976 murder of two of his schoolmates at the Tehran American School, fence inhabits the liminal conceptual space that narrowly divides self from other, experience from expression, and reconciliation from assimilation.

The work opened with points of light moving and swirling across the floor. The pattern of lights on the stage surface recalled the data points on a cluster graph or boosted photon signatures in a night-vision surveillance video taken by a drone flying over an otherwise featureless, pitch-black landscape. The projection lingered for a moment as the dancers began to populate the stage, one by one, creating the sense that the audience perspective was zooming in from a bird’s-eye view to a closer one, providing greater detail. The eponymous fence manifested most obviously in a floor-to-ceiling sculpture of mesh—evoking chain link—placed for the duration of the work in the corner opposite the Dance Studio’s audience entrance. With more subtlety, the fence marked the dancer’s bodies through costumes in a stark palette of black and gray, variously accented with metallic and mesh fabric. Gregory Catellier’s lighting design used strong, multidirectional spotlights from above that clearly picked out the dancers and their movements without ever completely illuminating the performance space. The sound design and composition by Ben Coleman provided an elegant pastiche of smooth electronic melodies, jarring percussive sequences, spoken word, sampling of classical and popular tunes, and moments of absolute silence in which the dancers’ bodies themselves became instruments of aural as well as gestural communication. Collectively, these elements of staging—costume, lighting, set, sound—rendered the stage as an indeterminate no-place lacking in stable temporal and geographic referents. It was alternately the desolate, misty front of a trench war, the quiet corner of a sinister dinner party, and “the vast, deserted landscape” that, according to the program notes, surrounds the Tehran American School in Staib’s memory.

fence, performance view, 2019 [photo: © Christina Massad]

fence, performance view, 2019 [photo: © Christina Massad]

On the whole, the dancers’ performances expressed a broad emotional range and technical polish throughout the equally wide-ranging vocabulary of movement for which Staib is well known. Of particular note, Laura Morton was alternately luminous and wickedly compelling. Jimmy Joyner, Virginia Spinks, and Gianna Mercandetti evolved a number of surprisingly rich and varied characterizations from a shared set of postures, gestures, and facial expressions. Chrystola Luu was majestic, creating a commanding stage presence with her gorgeous lines and fierce energy. Nicole Johnson was beautiful as well as tragic during moments in which she performed the struggle to control a shattered and unwilling body. Yet even as these gorgeously individual performances emerged, the choreography, the dancers’ attentiveness to their spatial and gestural relationships to one another, plus careful stage design and sound design linked the dancers into a cohesive ensemble. Like the space in which they performed, the dancers’ bodies seemed to lack stability as signifiers. They were not so much ambivalent, however, as multivalent. In the second movement the entire ensemble except for Johnson progressed along a diagonal toward James LaRussa to leap into his arms. He caught them and then gently set them aside. Each of these interactions between LaRussa and the other dancers was a reiteration of the same—or a very similar—movement sequence. As the sequence became reiterated, it evoked the subtle differences in individual memories of a collective event. It also, however, plausibly represented how very different individuals might experience a very similar trauma across disparate times and geographies. In the context of the work, the dancers’ long, slow progression across the stage and their final leap into LaRussa’s arms read as involuntary migration into the unknown or perhaps rescue from internment. And finally, just as plausibly, this progression of leap, catch, release performed how trauma plays out over and over in the mind of a single survivor, taking a slightly different form and causing a new injury with each recollection.

fence, performance view, 2019 [photo: © Christina Massad]

The choreography of fence insistently draws audience attention to the fact that the Dance Studio is “in the round” by demonstrating a lack of stable upstage/downstage or stage left/stage right distinctions. fence pitched the audience through a series of sometimes seamless and sometimes disorienting shifts in perspective. Some moments relied on a fairly certain shared audience response—as when the ensemble grimaced theatrically or laughed uproariously. At other times it was unclear whether the person sitting just to one’s left was seeing the same thing, much less someone sitting across the theater. Late in the evening-length performance, the dancers were arranged around the stage in tentative couples, barely trembling, intimately close to one another but not quite touching, each dancer facing in a slightly different direction. Depending on whose face one saw most clearly, and which couples were in closest proximity, one audience member might have read these tableaux as sweetly intimate moments of individualized reconciliation after violent community upheaval. Another, though, would have seen haunting portraits of alienation, or perhaps a final desperate resistance to assimilation and erasure. As a work, fence resists assimilation through classification. It was deeply affecting and rhetorically expressive, yet it lacked or perhaps deliberately buried a coherent narrative arc. It seemed to offer a warning—about the instability of identity, about the necessity of collaborative history-making, about the need to believe the firsthand accounts of survivors—without offering any comforting vision of how heeding its warning might deliver us.

Robin Wharton is a writer working in Atlanta, Georgia. She studied dance at the School of American Ballet and the Pacific Northwest Ballet School, and she was a member of Tulane University’s Newcomb Dance Company. She holds a law degree and a PhD in English, both from the University of Georgia.