Toyin Ojih Odutola: Testing the Name

Testing the Name, Installation view, 2018 [courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York]

Share:

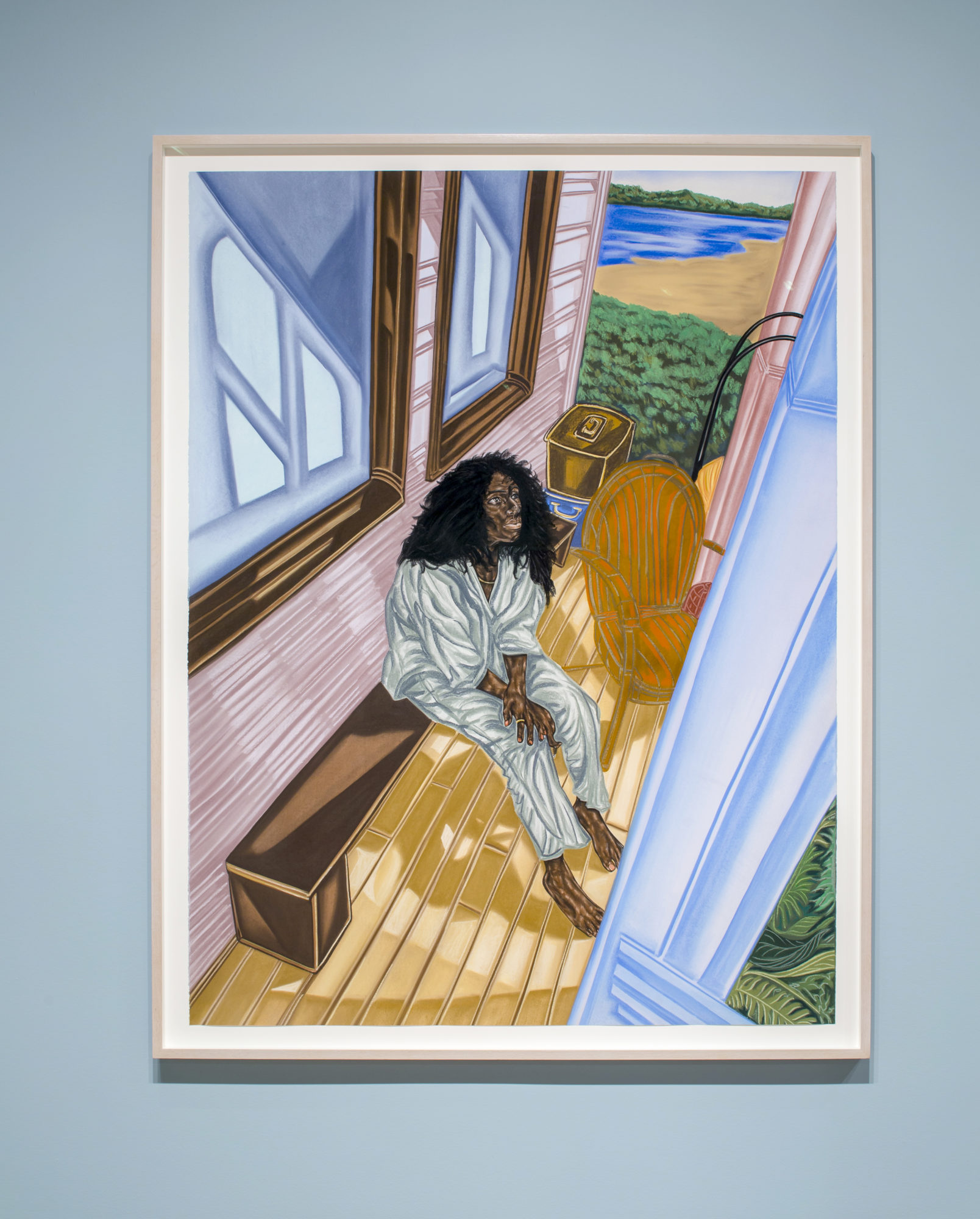

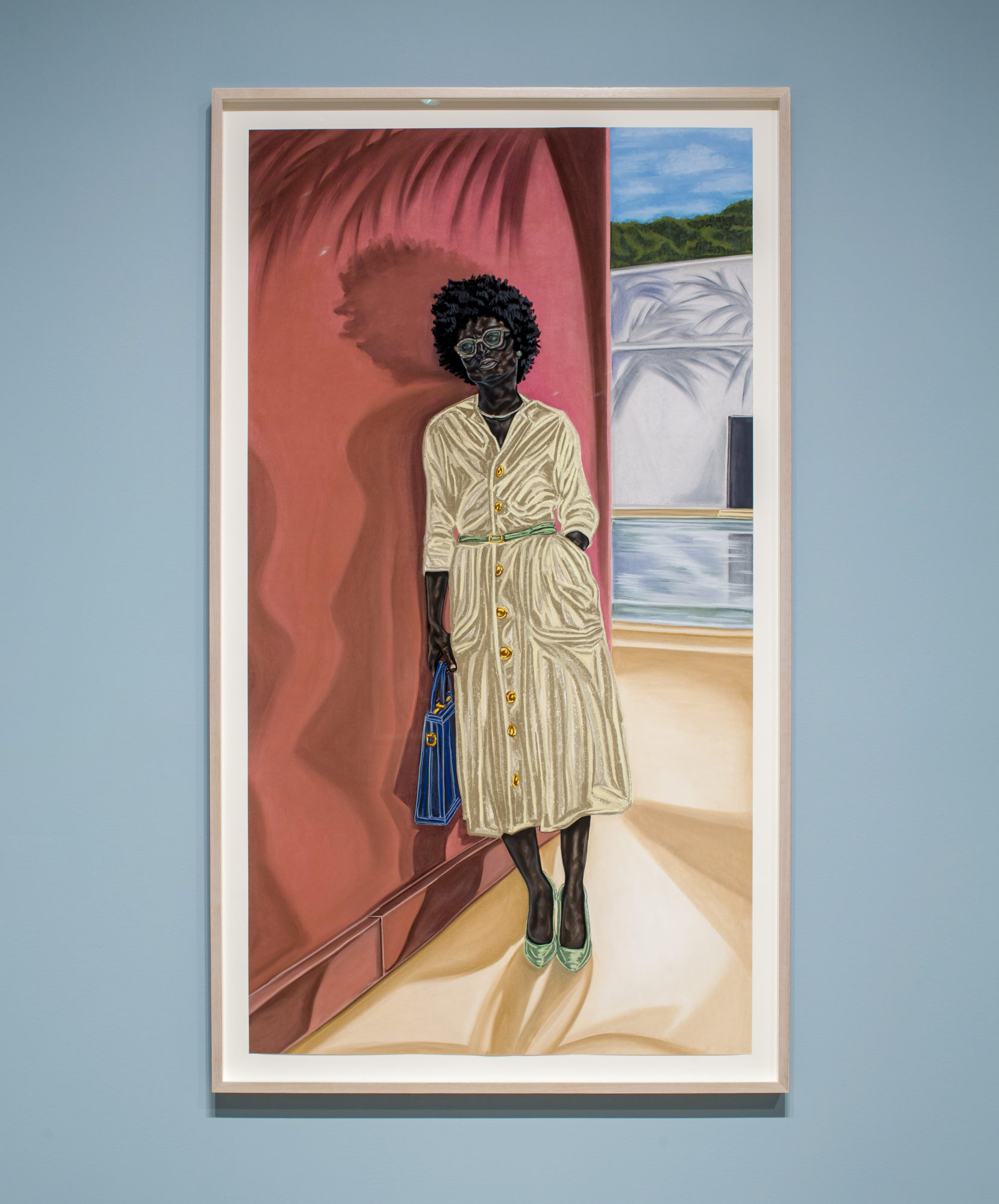

Artist Toyin Ojih Odutola’s Testing the Name [February 20–September 9, 2018] at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, GA, her third installment in a sequence of exhibitions documenting the fictional lives of two aristocratic Nigerian families united through same-sex marriage, opened less than a week after the theatrical release of the Marvel Studios film Black Panther. Like Ojih Odutola’s masterly, large-scale drawings, the film imagines an alternative history wherein generations of African wealth have replaced centuries of colonization and exploitation by European nations on that continent. In Wakanda, the fictional African country where the primary action of Black Panther occurs, as well as in Ojih Odutola’s episodic narrative of the UmuEze Amara Clan and the House of Obafemi, economic considerations provide subtle but essential context for these conjectures. Whereas Wakanda’s economic power depends on an imaginary metal called vibranium, the considerable privilege and cosmopolitanism conveyed by the luxurious surroundings of the figures Ojih Odutola depicts isn’t credited to a fantastical material resource but rather to the artist’s speculations about what wealthy Nigerian subjects could look like today had “colonialist meddling,” as she has called it, never occurred. The fact that this wealth is centered on—and allegedly being displayed by—a gay couple in Ojih Odutola’s richly conceived story is another fiction: a law signed by former Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan in 2014 prohibits public display of same-sex affection and criminalizes gay marriage.

Perhaps the most easily overlooked similarity between Ojih Odutola’s intergenerational queer saga and the Marvel film is the debt each owes to the visual storytelling strategies of comic books and graphic novels. While they could, because of their scale, be mistaken at a distance for paintings, Ojih Odutola’s works are large, sometimes life-sized drawings rendered in colorful chalk pastels, charcoals, and pencil. These drawings are rightly considered alongside figurative paintings by such contemporaries of the artist as Jordan Casteel and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, two other women of African descent who have garnered praise for their recent work engaging the genre of portraiture. But the panels of comic books, manga, and traditional Japanese woodblock prints are equally relevant, necessary comparisons.

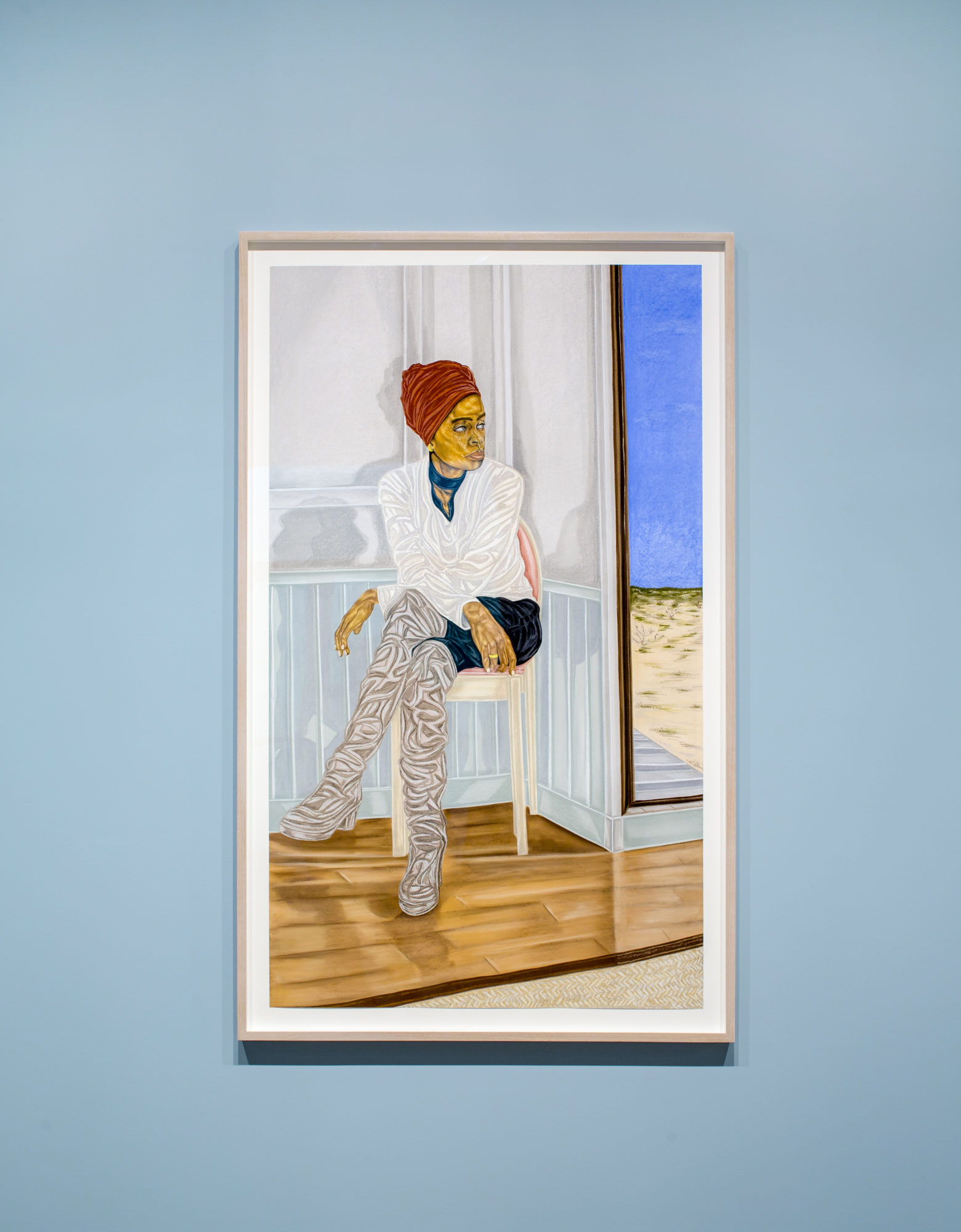

In the project she continues through Testing the Name, Ojih Odutola appears to pursue the narrative goals of a writer or novelist as much as those of a visual artist. It’s more than a coincidence that ballpoint pen, the medium in which she initially distinguished herself, is a writer’s tool repurposed for visual storytelling. In a Nabokovian, metafictional move, the artist gives herself a role within the story she’s fabricating, that of deputy private secretary at the Lagos estate owned by one of her fictional families. A female figure resembling Ojih Odutola and sporting the headwrap and knee-high boots that have become her sartorial signatures also appears in two drawings in Testing the Name. It’s ostensibly in her role as deputy private secretary that the artist informs the viewer, through vinyl wall text, about the temporary loan of artwork from the Obafemi private collection to the SCAD Museum of Art.

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Three Bless Heirs, 2018, charcoal, pastel, pencil on paper, 45 ¼ x 35 3/8 x 1 ½ inches [courtesy of the artist and Shainman Gallery, New York]

She blurs the distinctions between drawing and writing on a more literal level in the image that shares the exhibition’s title, Testing the Name, showing a handwritten letter from the Baron of Obafemi to his son, Lord Temitope Omodele. The image appears as a sheet of stationery that has been creased and unfolded repeatedly over many years, a piece of keepsake correspondence. Ostensibly sent while the young Lord Omodele was traveling accompanied by his future husband, Lord Emeka, on a London trip, the letter depicted in the drawing features the father’s warm, affectionate response to what may have been his son’s coming out. Describing Temitope’s childhood tendencies toward shyness, his father writes, “Have you forgotten you never need ask my permission for anything that may bring you happiness?” He continues, referring to the Omodele family’s work as ambassadors and traders: “We are a brilliant and independent bunch, who aren’t encumbered by expectation …. You are no longer that uncertain little boy, you are a man in love as I have been and so many others.” As the first work viewers encounter in Testing the Name, this epistolary drawing sets the stage for the rest of the exhibition, establishing a sense of the breadth and detail of the fictional world Ojih Odutola has conceived. The letter’s message may differ from what viewers would expect from a Nigerian father reacting to news of his son’s queerness, but this approach is typical of the unexpected juxtapositions that characterize Ojih Odutola’s visual narrative.

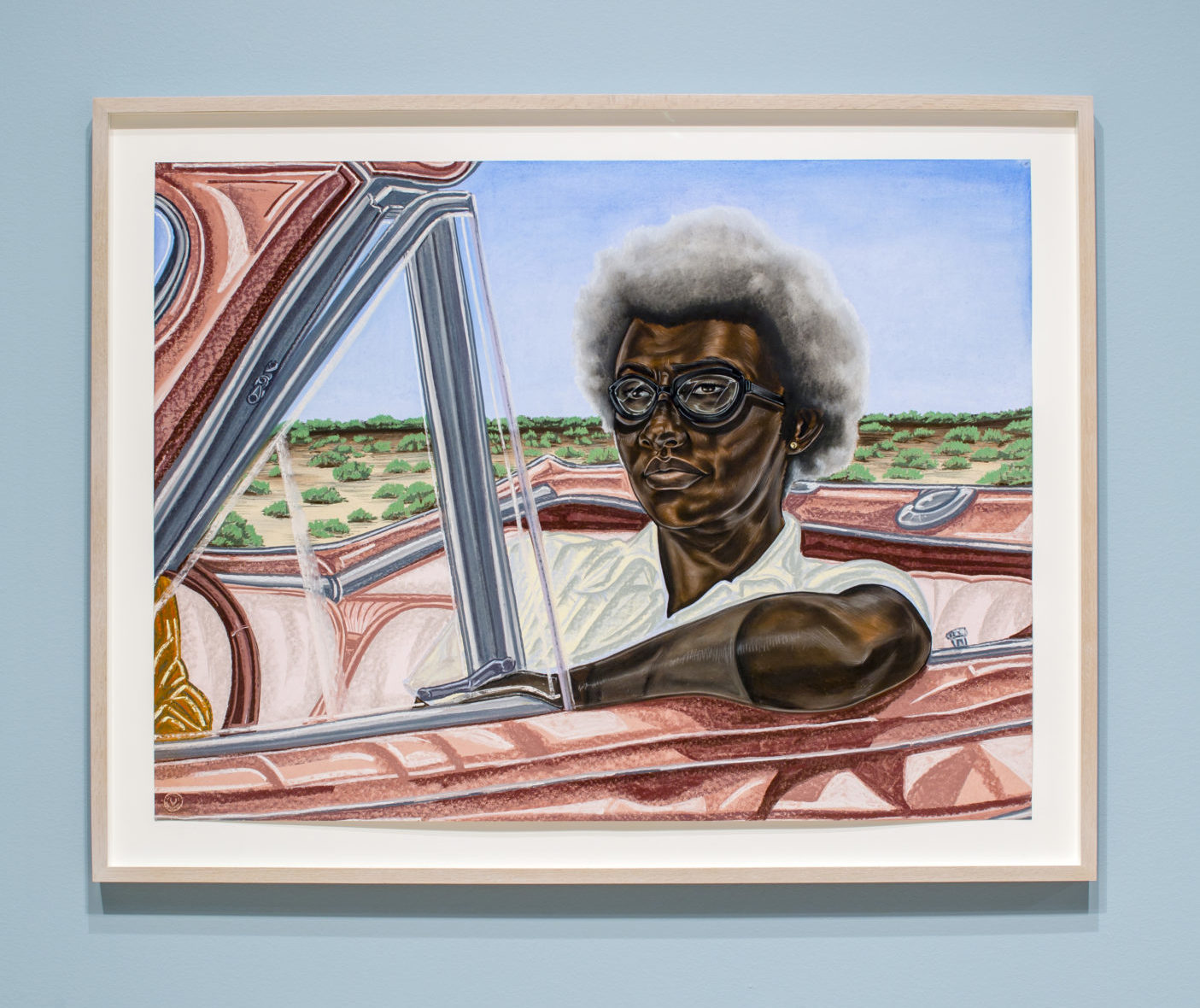

The works presented in Testing the Name, like ones that appeared last year in To Wander Determined at the Whitney Museum of American Art, highlight the Omodele side of the family and their globe-spanning work in the fields of diplomacy, commerce, and academia (the Emeka side of the family, who were the focus of the wryly titled exhibition A Matter of Fact, at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora in 2016, are members of the Nigerian landed gentry, not tradespeople). The associations with mobility, affluence, and leisure suggested by the occupations of the Omodele family create possibilities for narrative and geographic freedom not afforded to black subjects historically. This context also affects the temperaments and interior lives of Ojih Odutola’s characters, who are often distinguished by looks of indifference and detachment that completely disregard the viewer’s gaze. The steely visage of a gray-haired woman wearing driving gloves and goggles in the drawing A Solitary Pursuit leaves no doubt as to her right to be steering a pink convertible across the savannah.

Toyin Ojih Odutola, A Solitary Pursuit, 2018, charcoal, pastel, pencil on paper, 35 3/8 x 45 ¼ x 1 ½ inches [courtesy of the artist and Shainman Gallery, New York]

Because of the play of resemblances between figures, it’s clear that the moments depicted by drawings in Testing the Name occurred at different phases within the characters’ lives, but concrete details about who has grown up to become whom are sparse. The most plausible continuity is established by a pair of drawings showing the figure implied to be Lord Temitope Omodele, once as a youth alongside his unnamed brothers and again, presumably at a later date, with his future husband, Lord Jideofor Emeka. In the drawing of the Omodele brothers, Three Blessed Heirs, the trio is shown posing together as young men, with Temitope and one of his brothers each straddling a leg of the third brother as they face the viewer. The fraternal figures are intertwined, with fingers interlaced and hands grasping each other’s shoulders. Ojih Odutola’s inventive techniques for depicting the surfaces of skin, textiles, and interiors are on full display in Three Blessed Heirs: the creases and folds of the brothers’ garments are drawn with velvety texture in pastels and pencil, and their skin is rendered in the artist’s recognizable striated style. Each brother’s skin tone varies slightly, and it’s partially the darkness of Temitope’s skin that makes him recognizable from one drawing to the next. With representations of skin both formally and conceptually animating her work, this range of pigmentation among the Omodele brothers feels aimed at critiquing the pernicious effects of colorism and white supremacist ideologies on visual perception.

The Proposal, showing a more mature, bearded Temitope seated beside Lord Emeka, captures the instant just before the couple’s engagement. The scene appears to be taking place at an extravagant restaurant. A box implied to contain an engagement ring waits expectantly on the white tablecloth, insinuating potential action, just as the uneaten bonbon left on a nearby plate proffers sweetness. Both The Proposal and Three Blessed Heirs visually distill moments of intimacy between black men, once in a platonic, familial context and elsewhere in a romantic one. Undoubtedly these tender depictions function as an art-historical revision of images of black masculinity on one level, but to read them only as didactic would be to entirely miss the artist’s point about the paradoxical freedom and truth fiction provides. Same-sex marriage may currently be forbidden in Nigeria, but gay couples still live there, as they have for centuries, cherishing each other and imagining what could be instead—which is exactly what Ojih Odutola has done in this technically astounding and intricately conceived body of work. In Testing the Name, the artist demonstrates staggering capacities for craft and imagination, building an artificial world with the rich emotional and narrative texture of reality.