Three Case Studies in Ecological Protest

Engineer being escorted by a police officer, 2023 [courtesy of Atlanta Community Press Collective and DeKalb County Department of Planning Inspection]

Share:

At the time of this timeline’s original publishing in our Fall 2023 issue, Counter Ecologies, in Atlanta, the Stop Cop City/Defend the Forest movement is fighting the destruction of 85 acres of communal forest and the construction of a tactical police training ground, officially named the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center but known colloquially as Cop City. This timeline examines key events in the Cop City conflict alongside two historical case studies, separate in geography but united by an intersectional and international understanding that environmental injustice is a product of classism, colonialism, and racism. Under the logic of these far-reaching social biases, poor and working-class communities are deemed expendable.

Warren County, NC was host to the birth of the US environmental justice movement. From 1978 to 1982, a working-class Black community fought against the use of their land as a toxic-waste dump. In Sri Lanka, the Uma Oya multipurpose development project includes a hydroelectric dam whose ongoing construction has wreaked havoc on surrounding farmers’ land and homes. Uma Oya and Warren County serve as historical precedents for the Stop Cop City protests, but these movements are just two among many possible references.

The various constituencies within the Stop Cop City movement, the environmental activists who fought against the Warren County dumping grounds, and the protestors who oppose the Uma Oya dam were—and are—all unapologetically asserting their communities’ rights to clean air, land, and water. Their message is loud and clear: There can be no justice without environmental justice.

UMA OYA

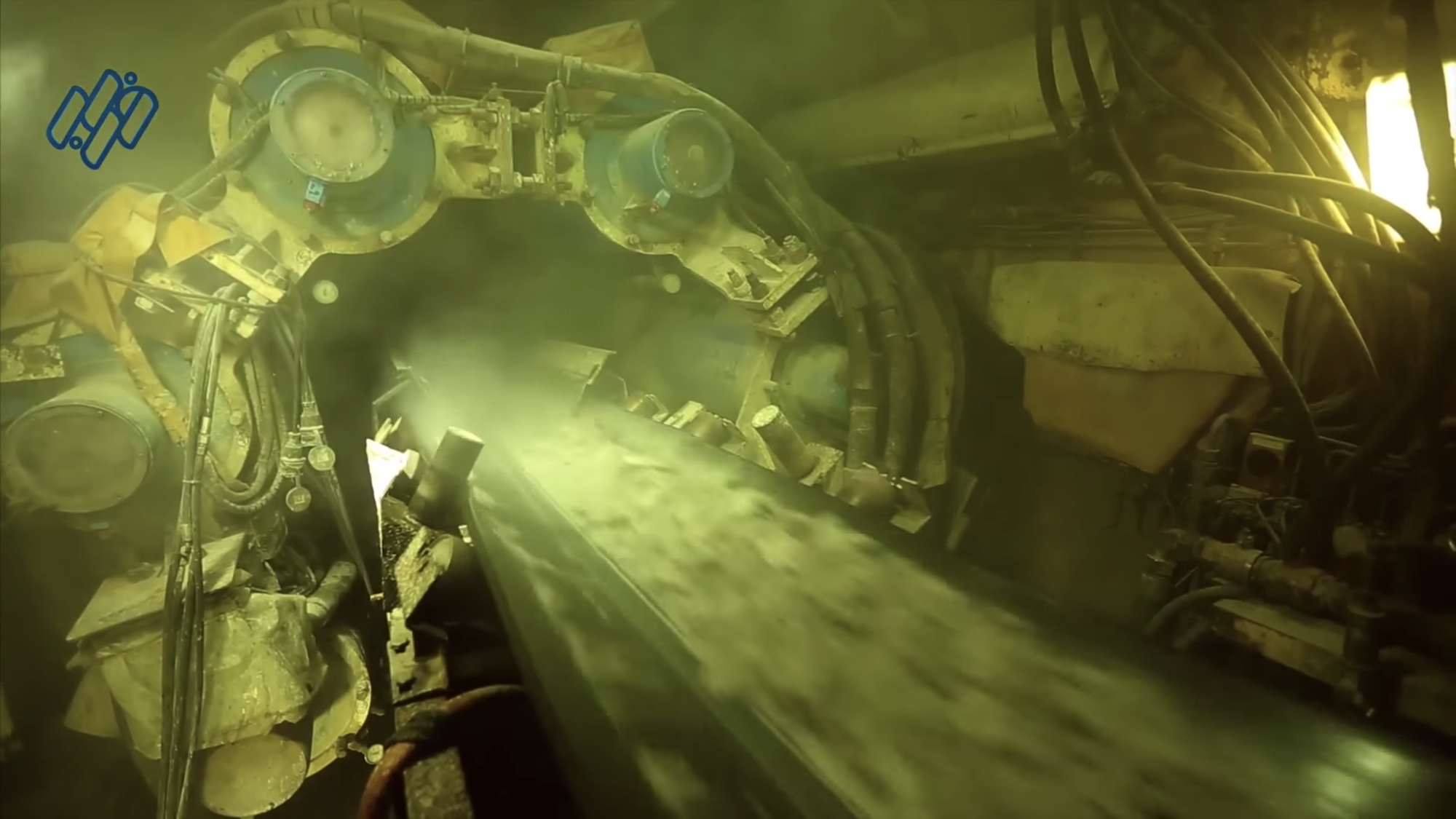

The Uma Oya catchment, a tributary of Sri Lanka’s Mahaweli River, spans more than 720 square km and is a vital source of water for local farmers. Due to heavy rainfall in the area, the catchment is prone to flooding. The Uma Oya Multipurpose Development Project was designed to divert a portion of the tributary to the Kirindi Oya basin, while simultaneously generating more than 231 GWh of hydroelectric power each year. The project was first proposed by the United Nations as early as 1959, but the proposal underwent numerous changes over the years, as technology advanced.1

1991

Sri Lanka’s Central Engineering Consultancy Bureau conducts a viability study of the proposed dams, but the project is rejected by the Asian Development Bank because of potential water rights violations.2

2000

Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Canada’s Lavalin Inc., and the Central Engineering Consultancy Bureau re-propose the project, this time receiving the go-ahead.3

2008

With funding secured from the Iranian government, the project’s foundation stone is laid in Wellawaya, Alikota-ara.4

2013

Construction begins5.

2015

Construction is temporarily suspended by Wasantha Aluwihare, the Sri Lankan deputy minister of irrigation.6

2016–2017

In late 2016 and early 2017, major environmental and infrastructural damage caused by the Uma Oya project come to light. Houses crack and collapse, forcing residents to flee their homes. A drought in June 2016, the effects of which are exacerbated by the project, results in a lack of freshwater for residents and their farmland. The Sri Lankan government fails to provide adequate resources for displaced and drought-affected families, which results in widespread disapproval of the project.7

June 2017: Residents in Bandarawela—a city affected by the project—rally to protest the environmental devastation caused by the development.8

2023

The project remains under construction.

Uma Oya Multipurpose Development Project Sri Lanka, 2017, screenshot [courtesy ofYouTube]

Uma Oya Multipurpose Development Project Sri Lanka, 2017, screenshot [courtesy ofYouTube]

Uma Oya Multipurpose Development Project Sri Lanka, 2017, screenshot [courtesy ofYouTube]

Warren County, North Carolina

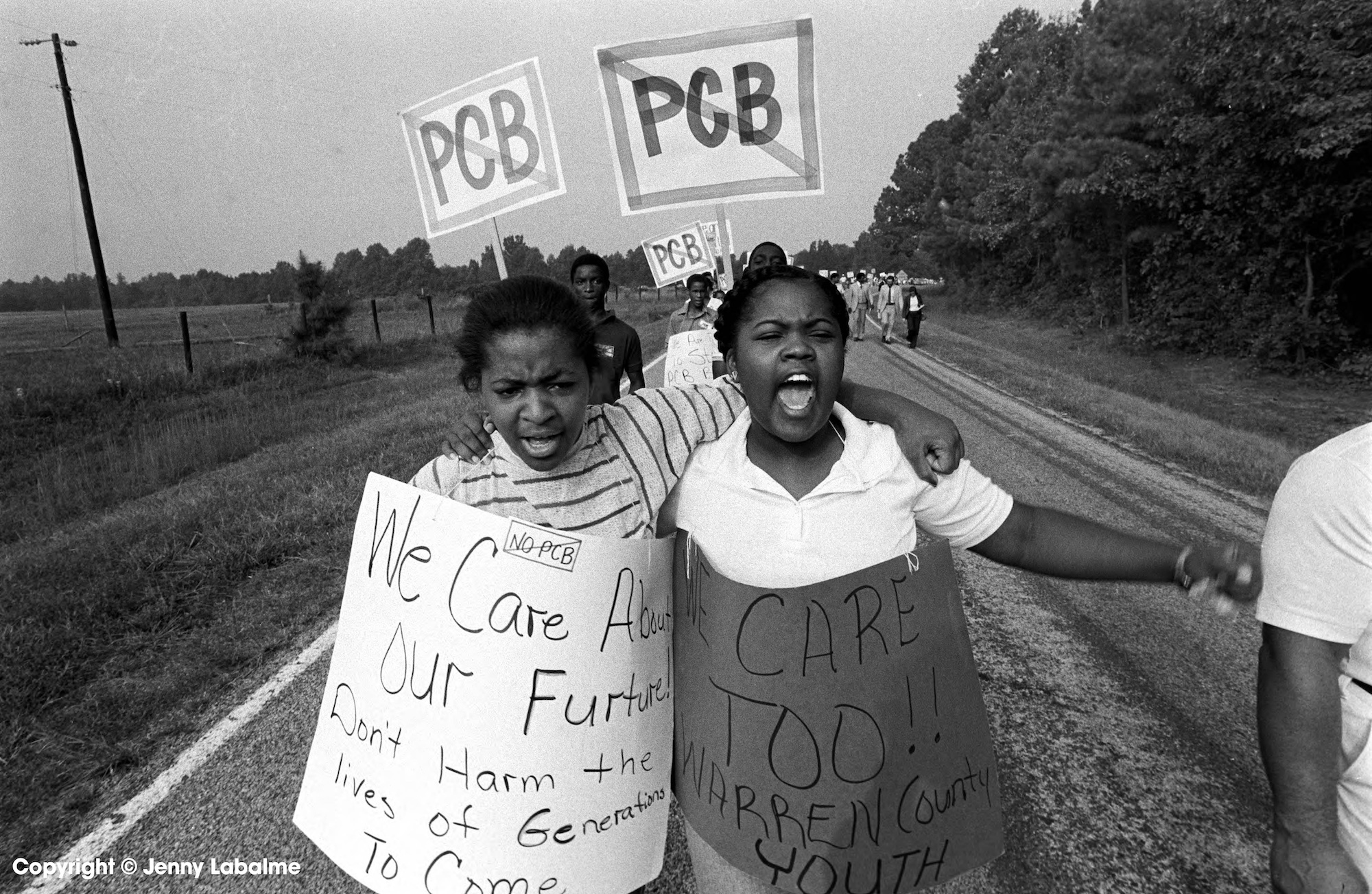

In 1978, attempting to evade costly EPA regulations, Ward Transformer Company begins disposing of its hazardous waste along North Carolina roads. Chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)—known to cause cancer and birth defects—seep into the earth and pollute farmland and critical bodies of water. A total of 31,000 gallons of waste is dumped, contaminating huge swaths of land and putting the health and safety of North Carolina residents at risk.9

1979

Gerald Ford’s 1976 Toxic Substance Control Act goes into effect, calling for contaminated soil to be disposed of in landfills. North Carolina state officials relocate the hazardous soil to Warren County, whose populace is mostly lower-income Black families. The first public hearing on the issue is held in January. More than 800 protestors voice their opposition to the proposed landfill. Over the next three years, numerous lawsuits against the dumpsite are filed, but none succeed in halting the plans.10

1982

Summer: $2.5 million is allocated to the creation and construction of the Warren County hazardous waste dumpsite. Opponents protest peacefully for six weeks. More than 500 people are arrested for demonstrating. Despite mass public disapproval, the landfill is constructed.

November: Several Black officials are elected to local office, giving the community a more representative voice. The Warren County protests mark the start of the environmental justice movement in the US.11

1994

Bill Clinton issues Executive Order 12898, titled “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations.” This order requires federal legislators to take environmental justice into account, and to dedicate attention and resources to the health and safety of historically neglected low-income communities of color.12

2012

Reverend Bill Kearney creates the Warren County Environmental Action Team to preserve Warren County’s history of environmental activism, and to continue advancing environmental justice locally.13

Jenny Labalme, A Road to Walk: Warren County PCB Demonstrations, 1982 [courtesy of the artist]

Jenny Labalme, A Road to Walk: Warren County PCB Demonstrations, 1982 [courtesy of the artist]

Jenny Labalme, A Road to Walk: Warren County PCB Demonstrations, 1982 [courtesy of the artist]

Atlanta Public Safety Training Center and the Defend the Forest + Stop Cop City Movements

In 2017, the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF) proposes tentative private plans for a roughly 160-acre police training facility, to be constructed in a section of the South River (Weelaunee) Forest known as the “Old Atlanta Prison Farm.” With an estimated cost of approx. $80,600,000, the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center comes to be known colloquially as Cop City.14

2021

April

Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms announces plans for Cop City.15

June 20–26

An environmental justice movement opposing the construction of Cop City—known as Defend the Atlanta Forest—hosts its first “Week of Action,” to facilitate “the building of direct relationships with the land that we’re fighting for ….” It includes a barbecue16, where attendees are informed about the Cop City plans.17

September 8

Atlanta City Council and APF approve a ground lease agreement for the construction of Cop City, reduced to 85 acres from the original 160. The Council hears more than 17 hours of public comment, in which most people voice disapproval of the project, but the council votes to approve the lease nonetheless.18

November

A second Week of Action takes place. Protestors build encampments and occupy Weelaunee Forest, where they create shared resources and establish a small community. This occupation lasts for several weeks.19 It is broken up by the DeKalb County Police Department. There are no arrests, but DCPD clears the site.20

2022

January

A second occupation of Weelaunee Forest begins.21

May

May 17: After further Weeks of Action, Atlanta Police Department (APD) begins making arrests for criminal trespass in the forest.22

July

More arrests are made during a Stop Cop City protest in Atlanta’s Little Five Points neighborhood. Georgia State Patrol and APD arrest 14 people, several of whom go on to sue for wrongful arrest.23

December

December 13: Five protestors and occupants of Weelaunee are arrested and charged with domestic terrorism during an early-morning police raid of the forest. Police fire pepper balls and spray tear gas at protestors. These arrests mark the first of many domestic terrorism charges in the Cop City protests.24

Overhead view of construction [photo: Nolan Huber-Rhoades; courtesy of Atlanta Community Press Collective]

2023

January

January 18: During a police raid the ongoing occupation in Weelaunee, Georgia State Troopers fatally shoot 26-year-old Manuel Esteban Páez Terán (they/them), known as “Tortuguita.” The Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) claims in the press that Tortuguita fired on state troopers, but no bodycam footage is released. Tortuguita’s killing marks the first time an environmental activist is slain by American police.25

January 19: An official autopsy conducted by the DeKalb County Medical Examiner’s office finds that Tortuguita suffered 57 gunshot wounds. It also states that there was no visible gunpowder residue on their hands. A more thorough gunpowder test is conducted, but the results are not released.26

January 21: During a protest in response to Tortuguita’s killing, six people are arrested in downtown Atlanta and charged with domestic terrorism.27

January 31: DeKalb County issues a land disturbance permit to the APF, which officially enables it to begin breaking ground and clearing the forest.28

February

February 13: A DeKalb County Commissioner, a Cop City construction advisory committee member, and the South River Watershed Alliance jointly file an appeal and injunction against the APF’s land disturbance permit, aiming to halt construction. A Fulton County Superior Court judge strikes down the injunction. An appeal remains ongoing.29

March

March 4–11: Occupation of the forest resumes for the first time since Tortuguita’s killing. The first 2023 Week of Action features a rally, film screenings, the Weelaunee Food Autonomy Festival, and a two-day music festival.

March 5: During the second day of the music festival, APD raids Weelaunee Forest and arrests 35 attendees—23 of those arrested are charged with state domestic terrorism.30

Activists return to the forest the following day and continue their occupation.

March 13: An independent coroner report is released and found that Tortuguita was fatally shot at least 14 times. The family’s attorneys argue that the report shows that at the time of their shooting, Tortuguita had their hands raised.31

Clear cutting of Weelaunee Forest [courtesy of Atlanta Community Press Collective]

May

May 4: The first preliminary hearings occur in which prosecutors argue the legality of domestic terrorism charges. The judge upholds the charges.32

May 15: Atlanta City Council hears more than seven hours of public comments, all of which oppose construction of Cop City. After the comments conclude, District 9 City Council Member Dustin Hillis proposes an ordinance to allocate $31 million of Atlanta city funds to APF, and to include a lease-back agreement that would allow APD and the Atlanta Fire Rescue Department to conduct training drills at the facility before construction is complete.33

May 24: Atlanta Community Press Collective reports that Cop City will cost upward of $51 million of taxpayer and private funds—almost twice the original estimate.34

May 31: APD’s SWAT team and GBI agents raid the home of three organizers behind the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, a bail support fund organization dedicated to “providing resources to protestors experiencing repression.” For the preceding year, the solidarity fund has primarily supported bail for protestors arrested while resisting Cop City. The organizers are arrested and charged with money laundering and charity fraud.35

June

June 5: The longest public comment session in modern Atlanta history occurs on the day Atlanta City Council it is slated to vote on funding approval for construction of the Cop City facility. Comments last roughly 16 hours. A wide majority oppose the project.36 In an 11–4 decision, the council votes to proceed with construction and allocates $67 million to the project.37

June 7: A coalition of organizers initiates a referendum to allow voters to decide whether they want Cop City’s lease to be rescinded. Organizers must collect 70,000 signatures by August 15 for the issue to be added to the November municipal election ballot.38

June 23: DeKalb District Attorney Sherry Boston announces that she will withdraw from prosecution of 42 cases against opponents of Cop City, including 29 charges of domestic terrorism. In her statement, Boston writes that she will “only proceed on cases that I believe I can make beyond a reasonable doubt.” The responsibility of prosecuting these cases is thus passed on to the attorney general.39

July

July 5: Andre Dickens, current mayor of Atlanta, holds a press conference during which he states “After all the protests, and the actions and events over the past few months, zero incidents of excessive force have been found,” despite the slaying of Tortuguita earlier the same year.40 A reporter asks, “Some of the protestors and opposers of the training center have begun taking signatures in the hope of having a referendum on the November ballot. Will you allow them to do what they’re doing now?” Dickens acknowledges that protestors have the right to collect signatures for a referendum before he calls the referendum’s legitimacy into question, replying, “We know that this is going to be unsuccessful if it’s done honestly.”41

Memorial for slain environmental activist Tortuguita, 2023 [photo: Matt Scott; courtesy of Atlanta Community Press Collective]

Karina Teichert is a writer, filmmaker, musician, journalist, curator, and community advocate from Atlanta. They hold a BS in literature, media, and communication from the Georgia Institute of Technology. Teichert is the inaugural ArtTable fellow for Art Papers. Their passions lie in the intersection of journalism, art, community, and the DIY ethos. Their writing has been published in Burnaway and Record Plug Magazine.

References

| ↑1, ↑2, ↑3 | Upaka Rathnayake and D.M. Suratissa, “Uma Oya multi-purpose development project, Sri Lanka; flood management and social impacts,” Water New Zealand no. 194 (May 2016): 44–47, online. |

|---|---|

| ↑4, ↑6, ↑7 | Dineth Rathnayaka, “Uma Oya Development Project: Multi-Purpose or Multi-Destructive?,” Daily Mirror, January 3, 2017, online. |

| ↑5 | “Uma Oya Powerstation,” Amberg Engineering, online. |

| ↑8 | “Protest against Uma Oya Project.” Onlanka, June 28, 2017, online. |

| ↑9 | Matt Reimann, “The EPA Chose This County for a Toxic Dump Because Its Residents Were ‘Few, Black, and Poor,’” Timeline, April 3, 2017, online. |

| ↑10 | Jenny Labalme, “A Road to Walk – Author Jenny Labalme Captures Warren County Protests.” A Road to Walk, online. |

| ↑11 | Matt Reimann, “The EPA Chose This County for a Toxic Dump Because Its Residents Were ‘Few, Black, and Poor,’” Timeline, April 3, 2017, online. |

| ↑12 | “Environmental Justice History,” U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management, online. |

| ↑13 | “Remembering Warren County: North Carolina and the Continuing Struggle for Environmental Justice,” North Carolina Museum of History, online; “Initiatives,” Warren County African American Historical Collective, recorded April 20, 2023, online. |

| ↑14 | “Vision Safe Atlanta: Public Safety Action Plan Infrastructure,” Atlanta Police Foundation, 2017, online |

| ↑15 | Kendall Glynn, “Cop City Explained: A Look at the Ongoing Controversy Surrounding Police Training Center,” Decaturish, September 1, 2022, online. |

| ↑16, ↑19, ↑21, ↑23 | Conversation with Matthew Scott of the Atlanta Community Press Collective, June 22, 2023. |

| ↑17 | Defend the Atlanta Forest, “Week of Action: June 20-26,” Facebook, June 3, 2021, online. |

| ↑18 | Taiyler S. Mitchell, “Atlanta Wants to Build an 85-Acre ‘Cop City.’ These Groups Are Trying to Stop It.” HuffPost, April 8, 2023, online. |

| ↑20 | Natasha Lennard, “An Uncompromising Coalition Is Building Support to Nix Atlanta’s ‘Cop City.’” The Intercept, August 18, 2022, online. |

| ↑22 | “Rocks, Possible Molotov Cocktail Thrown toward Officers at Future Home of ‘Cop City,’ APD Says,” 11Alive, May 17, 2022, online. |

| ↑24 | Odette Yousef, “Domestic Terrorism Charges in Georgia Are Prompting Concern over Political Repression,” NPR, June 29, 2023, online; Sanya Mansoor, “Atlanta Cop City Protesters Charged with Domestic Terorrism,” Time, May 4, 2023, online. |

| ↑25 | Dianne Mathiowetz, “The Killing of Forest Defender Tortuguita in Atlanta,” Workers World, January 24, 2023, online. |

| ↑26 | Nick Valencia et al., “Climate Activist Killed in ‘Cop City’ Protest Sustained 57 Gunshot Wounds, Official Autopsy Says, But Questions About Gunpowder Residue Remain,” CNN, April 20, 2023, online. |

| ↑27 | Edwin Rios, “Atlanta Police Charge 23 with Domestic Terrorism amid ‘Cop City’ Week of Action,” The Guardian, March 6, 2023, online; Andy Rose et al., “Charges Announced for Those Arrested in Protests over Controversial ‘Cop City’ and Fatal Police Shooting of Activist,” CNN, January 23, 2023, online. |

| ↑28 | “DeKalb County Releases 11-Month Public Safety Training Center Permitting Timeline,” 11Alive, January 31, 2023, online. |

| ↑29 | Dan Whisenhunt, “Judge Denies Request for Restraining Order to Stop ‘Cop City’ Construction.” Decaturish, February 22, 2023, online. |

| ↑30, ↑34 | “Week of Action Begins This Saturday with Protest at Gresham Park,” Defend the Atlanta Forest, press release, March 1, 2023, online. |

| ↑31 | Tess Owen, “Police Shot ‘Stop Cop City’ Activist 14 Times With Their Hands Up, Independent Autopsy Shows,” VICE News, March 13, 2023, online. |

| ↑32 | “Judges Uphold Domestic Terrorism Charges against Activists,” Atlanta Community Press Collective, May 8, 2023, online. |

| ↑33 | “Backroom Deals and Elasticity Clause Increase Public Cost of Cop City,” Atlanta Community Press Collective, May 24, 2023, online. |

| ↑35 | Ryan Fatica, “Three Atlanta Activists Arrested, Home Raided over Bail Fund,” Unicorn Riot, May 31, 2023, online. |

| ↑36 | Pamela Kirkland, “Atlanta City Council Approves Millions in Public Support for Controversial ‘Cop City’ Training Facility,” CNN, June 6, 2023, online. |

| ↑37 | Timothy Pratt, “Real Cost of ‘Cop City’ Under Question After Atlanta Approves $67M For Project,” The Guardian, June 9, 2023, online. |

| ↑38 | Timothy Pratt, “Activists Push for Referendum to Put ‘Cop City’ on Ballot in Atlanta,” The Guardian, June 16, 2023, online. |

| ↑39 | “DeKalb District Attorney Withdraws from Alleged Cop City Cases,” Atlanta Community Press Collective, June 24, 2023, online. |

| ↑40 | Mariya Murrow, Mariya. “Atlanta Mayor Says ‘Anarchists’ to Blame for Recent Vandalism,” Atlanta News First, July 5, 2023, video, 24:09, online. 04:59 |

| ↑41 | Murrow. 23:50 |