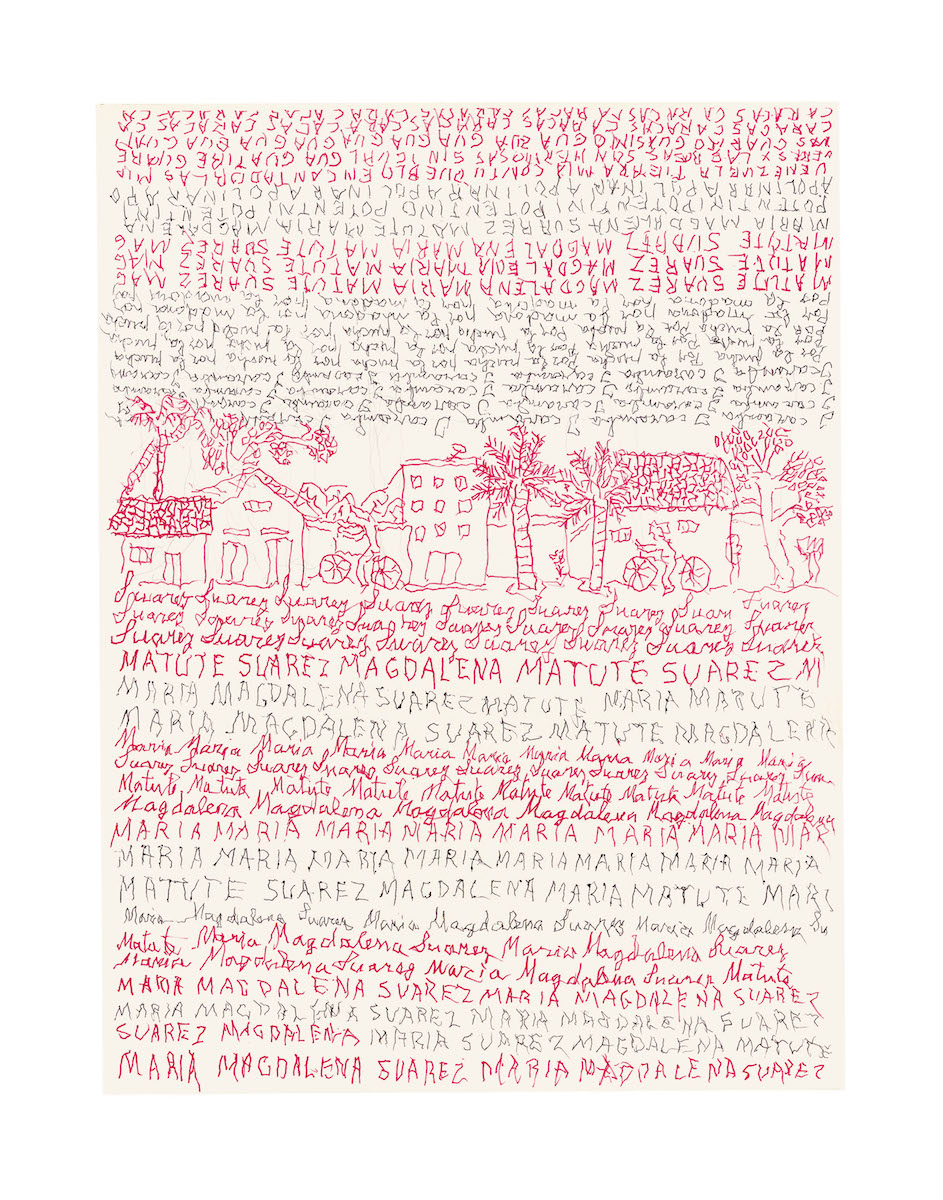

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess—The Finest Disregard

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Magdalena Suarez Frimkess: The Finest Disregard, installation view, 2024 [photo: © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Share:

A bewildering ceramic Minnie Mouse dressed in a palm tree–patterned shift stared out from a showcase at the entrance to Magdalena Suarez Frimkess’ first museum exhibition, The Finest Disregard [August 18, 2024–January 5, 2025], at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Despite her cheerful attire—blue pumps, pink handbag, and flowered hat—her thinly painted smile and wide eyes belied a sense of unease, a feeling that perhaps not everything was as it seemed.

Although many animated characters—Donald Duck, Wonder Woman, Betty Boop—are rendered across the show’s 178 drawings, paintings, and ceramics, Minnie seemingly recurs with the most frequency and in the most poignant postures. Elsewhere, she stands forlornly atop a circus carousel jar; she lies flat, side-by-side in a row of multiples; and sits, aside Popeye, in a horseless cage like cart. She’s even replicated, along with or in lieu of, the artist’s signature in other, larger works.

Initially conceived as a free-spirited flapper girl in a role equal to her male counterpart’s, within the first decade of her inception, Minnie was reduced to a damsel in distress, who then transitioned into a housewife in an apron and bonnet, rarely seen outside the domestic sphere. Not until 2011, 83 years after her creation, did a television show debut bearing Minnie’s name. And it was not until 2018 that her star was added to the Hollywood Walk of Fame, forty years after Mickey received one.

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, XXL Minnie Mouse, 2009 [photo: © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist, collection of Karin Gulbran and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Untitled, 2013, [photo: © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, gift of Jonas Wood and Shio Kusaka]

Of course, it is a matter of fatuous coincidence that Suarez Frimkess was born only months after her beloved alter ego, in 1929, and that she was 84 when she had her first solo exhibition at South Willard in Los Angeles, roughly 40 years after her ceramicist husband and frequent collaborator Michael Frimkess’ first solo show.

And yet, there’s certainly more to her use of animated figures than meets the eye, as the artist acknowledged in a recent interview when she explained that cartoons were “a kind of cover. You won’t be attacked for expressing your ideas because it’s funny.” Of humor, Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin said it is “one of the essential forms of the truth concerning the world as a whole,” and therefore just as appropriate and useful as solemnity for addressing universal issues. Certainly, Suarez Frimkess’ ceramics broaden universal conceptions of love, sacrifice, injustice, and art, truths ascertained from a full and, at times, unfathomable life.

Now 95 years old, Suarez Frimkess began painting at age seven, while in the care of nuns at a Catholic orphanage in Caracas, Venezuela. Her early artistic virtuosity prompted them to send her to study at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas, the most esteemed art school in the city. The paintings and prints that followed were highly acclaimed by faculty and visiting artists. When she turned 18, and had no means of supporting herself, she entered into a union with an older man who was separated but not yet divorced. They abruptly moved to Chile and started a family. Ten years later, the artist returned to artmaking, took sculpture courses, and quickly became “the most daring sculptor now working in Chile,” according to a 1962 issue of Art in America.

“I’d been a mother for many years. Across history, women have to have children and get married; there’s no profession in the arts for them. So, I gave it up and took it like a hobby, more or less,” explained Suarez Frimkess in a recent documentary portrait by Mary Wigmore. “Then something itched, and I said I have to go back to that.” When she was offered a residency at the Clay Art Center in Port Chester, NY, the father of her children told her that if she left, she couldn’t come back. Her unrelenting conviction ultimately drove her to choose art and move to the United States, despite the heart-wrenching consequences.

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess met her husband, Michael Frimkess, soon after arriving at the Clay Art Center, but they did not start collaborating seriously until they moved to Los Angeles and he developed multiple sclerosis. When it became too difficult for him to produce his own work, Magdalena began painting his thin-walled, classically proportioned pots with hand-mixed glazes. She did so while also caring for the house and their daughter, designing and selling clothes, and occasionally creating work of her own from discarded scraps of clay. Throughout, she refused to learn to use a wheel or any other formal ceramic techniques. Instead she applied the unconventional, surrealist-inflected approaches she developed in her early sculpture career.

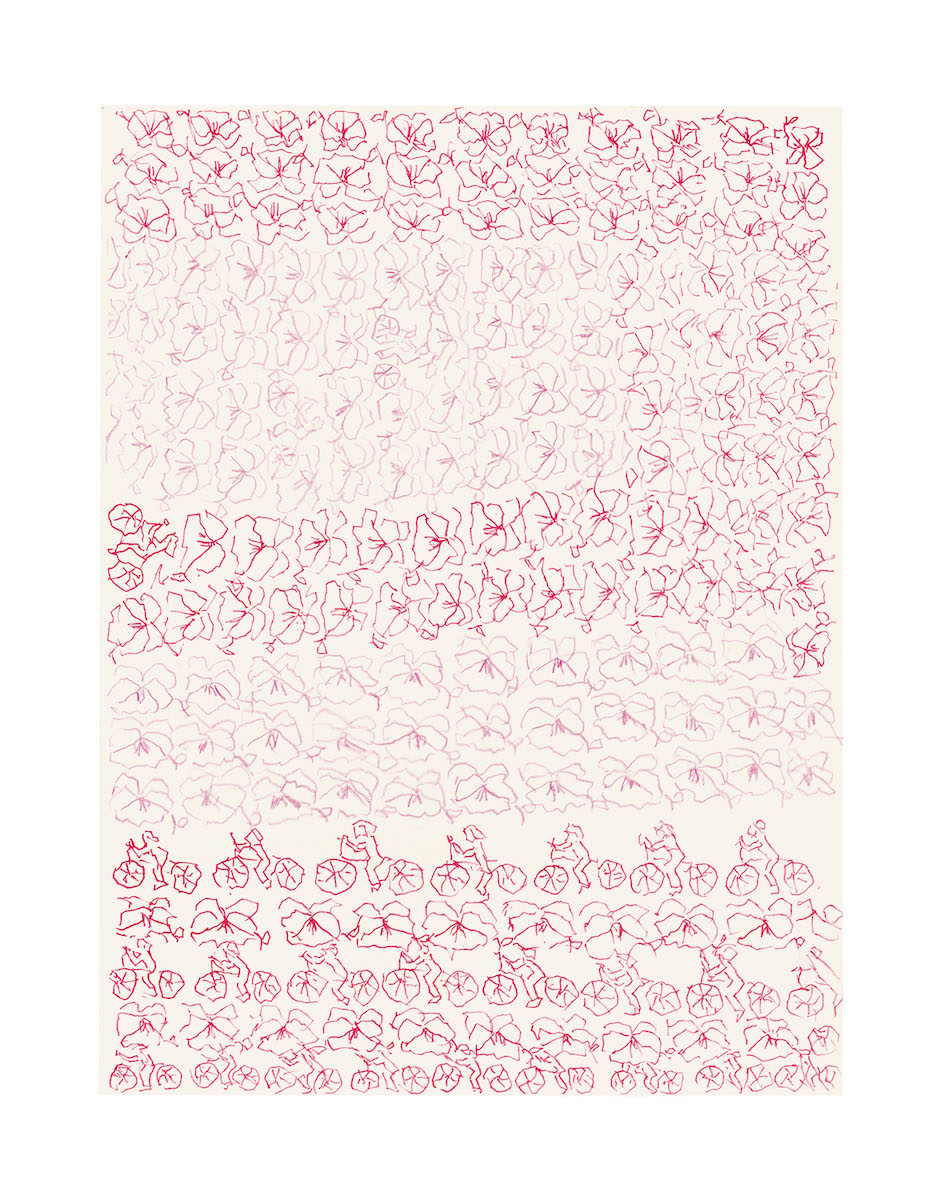

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Drawing, 2014, pencil on paper, 15.75 × 11.75 , [photo: Ruben Diaz © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist Mark Grotjahn and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Drawing, 2014, pencil on paper, 15.75 × 11.75 , [photo: Ruben Diaz © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist Mark Grotjahn and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Even her utilitarian tableware—tortilla plates and coffee mugs—appear sculptural, not functional. Whereas many ceramicists, including her husband, take great pains to rid their work of evidence of their physicality, eradicating touch, pressure, emotion, and kinetic energy, Magdalena’s sculptures quiver with her presence. Fingerprints, pinch marks, patchwork, the spontaneity and surety of her brushstrokes altogether engender a perceptible alive-ness. As the show’s title, The Finest Disregard, suggests, her feelings about convention and perfection are not on account of amateurism or ineptitude but in obedience to a higher designation, a rarefied vision.

To that end, the inconsonant tension between husband Michael’s flawless Grecian urns and Magdalena’s emphatic, unexpected imagery affords the collaborative works their dynamism and striking emotional resonance. The towering, nearly 60-inch black Chinese temple vase, Mercado Persa 1996, bears luminous miniatures of beloved friends and family, her signature cast of cartoons—including Condorito, an anthropomorphic condor of the eponymous Chilean comic strip—commercial logos, and such historical figures as George Washington and Venezuelan military hero Simón Bolívar. The mesmerizing vessel feels like a scrapbook: autobiography overlayed with history, fantasy, and everyday mundanity.

Magdalena also relied on the propriety of Michael’s vessels to mask her more pointed political tableaux. For example, enwreathing the lid, neck, and base of Untitled (Lonely Heart, MLK, AD, FC) 1970 are elegant bands of black floral ornamentation; in the center, rendered in faded cerulean, is an idyllic scene of social revolution that includes Martin Luther King Jr., Fidel Castro, and Angela Davis. Píntame Angelitos Negros (1972)—referencing an Andrés Eloy Blanco poem exposing the ethnic discrimination behind many social and religious representations—emulates a traditional Chinese blue-and-white porcelain vase, with crisscrossing scrollwork that frames images of various Incan women in irreverent postures, including one with a frayed rope around her neck as if she’d just broken free from the noose of helotry.

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Mercado Persa, 1996 [photo: Marten Elder © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist, kaufmann repetto Milan/New York, the Michael Frimkess Trust, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

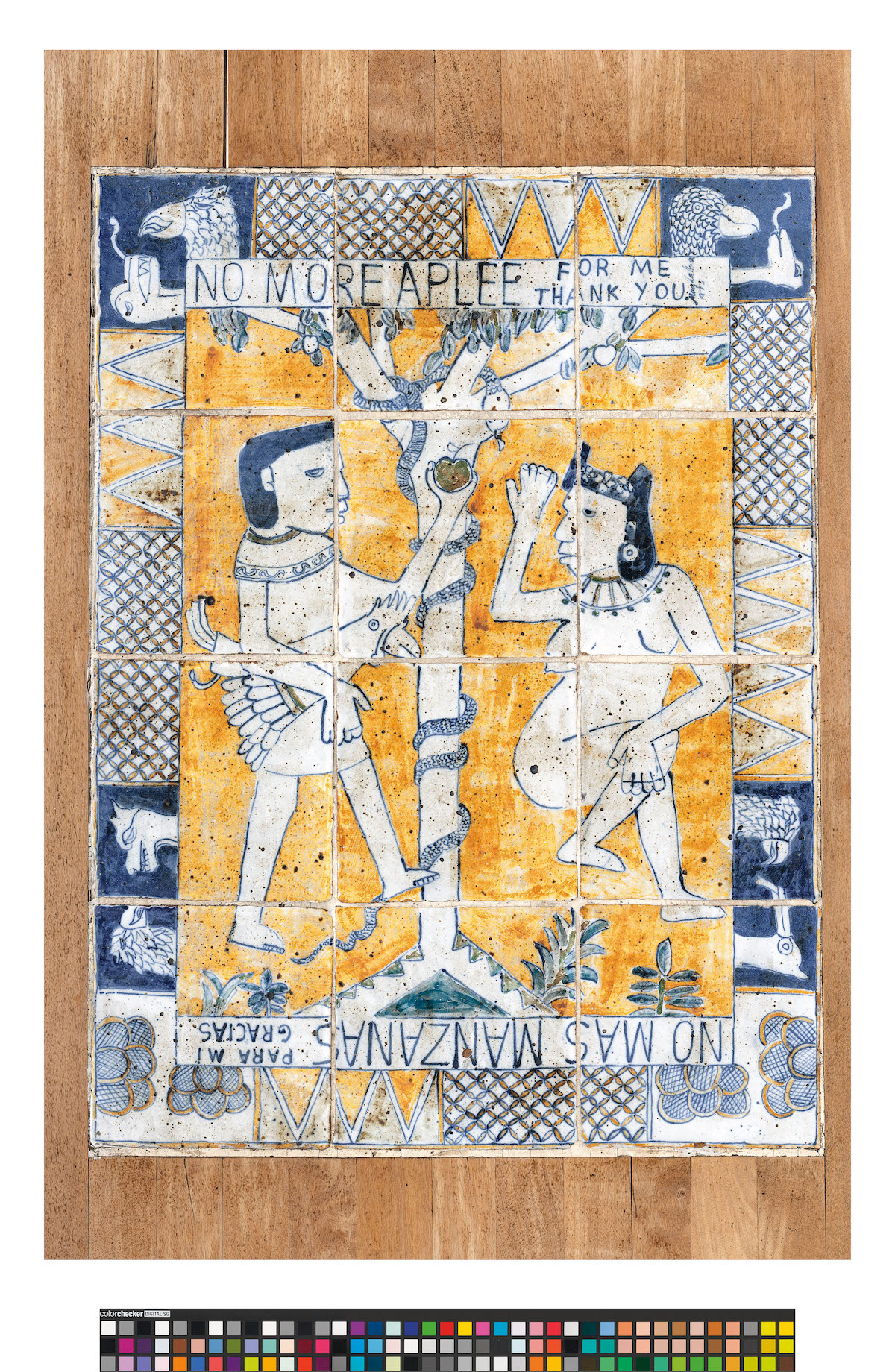

Of her many feminist works, a table inlaid with antiqued, painted tiles is one of the more explicit. Recasting the biblical story of Adam and Eve with Mesoamerican imagery, her Eve rejects the apple Adam holds before her. The exclamation painted in blue above her head reads, “No more apples for me, thank you”; it appears again, in Spanish, beneath her feet. Considering the prevalence of state-sanctioned censorship here, and in her home country, and the continued social and political subjugation of women, the table’s meaning and its formal irony feel just as urgent today as in 1973, when it was made.

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Untitled (No more apples for me), 1973 [photo: © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist, collection of Delia DeSasia, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Untitled (No more apples for me), 1973 [photo: © Museum Associates/ LACMA; courtesy of the artist, collection of Delia DeSasia, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles]

Other pre-Columbian women, often depicted admiring themselves in handheld mirrors, adorn various trays and vessels in the exhibition. When the women’s eyes meet mine in the illusory reflecting glass, I can’t help but see the artist winking at me—a reminder that not only is she in on the joke, but so am I. As with Minnie’s fugitive smile, the truth hides in plain sight.