The Eyes Were Always on Us

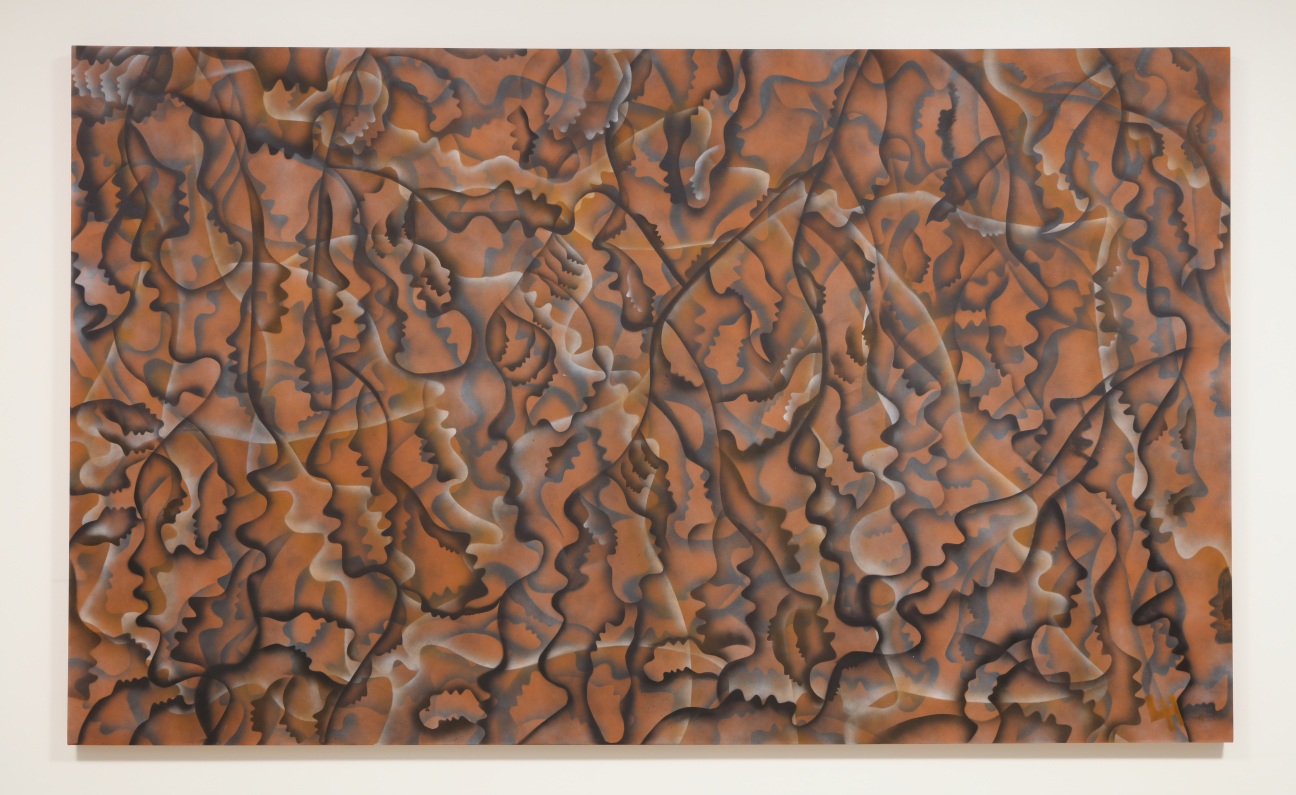

Lonnie Holley, We Were Like the Rivers, 2023, acrylic, gesso, and spray paint on canvas, 72 x 120 inches, [courtesy of the artist and UTA Artist Space, Atlanta]

Share:

The Eyes Were Always on Us opened March 23 at the United Talent Agency’s new Atlanta gallery on Peachtree Street—a highly anticipated debut for the Beverly Hills–based, all-in-one creative agency. I made it back to Atlanta on a Sunday and was lucky to see the show privately. It was a great pleasure to return home and see the first Atlanta solo exhibition in several years of Alabama-born, Atlanta-based artist Lonnie Holley. The choice to exhibit new works (all 2023) by the enigmatic Holley has eroded my initial skepticism about the UTA space. Holley belongs to the Black American vernacular canon, one of the only artistic traditions that is truly native to this country. And although the term vernacular is one most often imposed to mark abjection, it is also sovereign in nature. His biography is biblical, an unfathomable sequence of captivity and flight. Holley personifies American liberty. Albeit counterintuitive, the American South is the leading exporter of the world’s finest freedom narratives, and continually produces a surplus of them, despite our seemingly insatiable appetite. The triumph of Holley’s art stardom lampoons the imperio-colonial project. His musical and visual contributions, however, do not. I’ve heard that Holley plays only the black keys.

We Were Like the Rivers is the painting I greeted first as I descended into the UTA gallery space. These paintings consist of overlapping, ghostly figures in tectonic shale whose silhouettes and outlines intersect to form a cartography. Tributaries converge and divert across the canvas, down south. It is the Delta, but the painting’s bottom layer is clay colored, resembling the iron-rich earth of the Piedmont region. America’s industrialization of post–Civil War Southern cities—such as Atlanta, Birmingham, and Charlotte—happened throughout this region.

Lonnie Holley, We Were Like the Rivers, 2023, acrylic, gesso, and spray paint on canvas, 72 x 120 inches, [courtesy of the artist and UTA Artist Space, Atlanta]

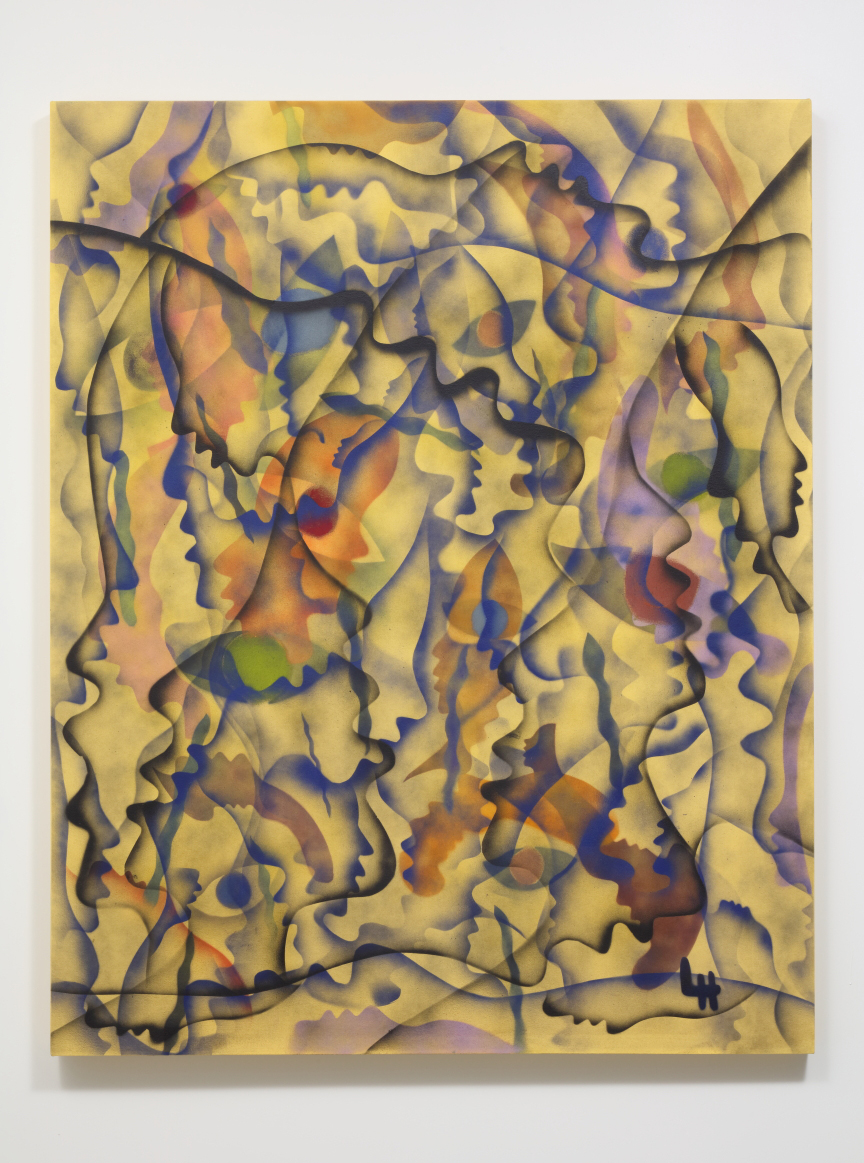

Holley’s work is vocational. He—and everything he does—is devoted to the ones who came before. Reverence for the dead is a large part of social life in West Africa and has continued throughout the diaspora. Initially, these paintings struck me as grave sites, an easy reading given the relationship the artist has had with graves. They are and are not, simultaneously. Death is a threshold and the onset of a voyage. These paintings are about passage, not entombment. The presence of the titular eye in the painting that lends its name to the exhibition demonstrates this dichotomy.

The Malagasy people in Madagascar have a tradition of re-interment. A funeral continues until the Famadihana ceremony, when they return to their loved ones’ graves and turn the bones. The Malagasy believe that only once the body has fully decomposed is the transition to the afterlife complete. With this understanding of death, remembrance can’t be sequestered to a cemetery plot. The Eyes Were Always on Us is the only painting in the exhibition that incorporates an eye motif. There is breath and song on the lips of these silhouettes as they convene. The profiles in Holley’s paintings lack gender or identity, apart from their Blackness. The sociality Holley represents here reminds me of the ungendering queer social space of the hold that Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley speaks of in her canonical essay Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic. The hold of a slave ship, the belly, swallowed Africans and birthed a new people through unimaginably inhumane conditions. People were thrown together, and social bonds forged without regard for kinship, nationality, or sex. These relationships were inherently radical and queer, simply because cargo isn’t supposed to be in relation.

Lonnie Holley, The Eyes Were Always on Us, 2023, acrylic, gesso, and spray paint on canvas 71 x 96 inches [courtesy of the artist and UTA Artist Space, Atlanta]

For those who were treated as property, and for their descendants, to engage in the making of things—things with no use-value—is inherently radically political. An “object” making such objects is the object’s resistance. This act requires nothing didactic to make it so. Holley’s sculptural objects are excessive with regard to this emergent phenomenon. But what does it mean for him to make images—what is resituated or ruptured by his engagement with painting? Is his ethic of salvage continued onto stretched canvas?

I imagine Holley’s paintings being made on the floor of his studio, which is incorrect. I tend to project this fantasy onto paintings I enjoy. In this exhibition, and in Holley’s painting practice generally, most works don’t seem to have, or need, a top or a bottom. The wall, therefore, becomes antagonist. It precedes the image—and the captive—and is a necessary condition in the production of either. But the wall acquiesces to Holley, who makes it do his bidding—as he does with the image, too. The negro is an aesthetic construct, an image against which the rest of the world’s claim to personhood is confirmed. Blackness is the Lacanian imago. Holley’s paintings, regardless of their orientation, reorient the site into sight, into image, and onto the audience and space. The faces and the bodies depicted are upright, postured, dignified, and in motion.

Holley’s paintings exist outside the pictorial history of European painting. He plays with subject-background relations, employing them in narrative ways and often placing the silhouettes atop an initial layer of intersecting contours, where they meld. The background and the community are distinct but bound to each other. Unalloyed, his work is evidence that, as with song and cuisine, material culture also traveled across the Atlantic—a culture that preceded, and seeded, cubism.

Lonnie Holley, The Eyes Were Always on Us, installation view, 2023 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the artist and UTA Artist Space, Atlanta]

Holley’s works on paper implement this approach and this dynamic the most. Among them, Searching for Another World’s eccentric cosmos imagines a prototypical galaxy in mid-formation. Its clustered series of eclipsing, orbiting hardware—nuts, washers, and a film reel, all used as stencils—are tokens signifying Holley’s commitment to repair. Time slips in this painting—it’s before and beyond.

Calling Mama is the simplest composition among the included works. I can perceive the moment at which he resolved it, as if its abrupt and succinct arrival is a recollection I possess. The title stands out, as well, as the most sentimental in the show. Other works’ titles make grand, world-claiming proclamations that are wide and outwardly positioned. Calling Mama doesn’t. These two words conjure so much for me and carry me to Holley’s childhood, where mother and child are separated. I think about his abduction from his mother, by a woman in whose care his mother had placed him. Holley was lost, stolen, sold, discarded, captured, imprisoned, and eventually rescued, all by people who promised to protect and care for him. I also ponder the all-too-familiar, recurring, desperate pleas of boys and men scared for their lives, calling for their mothers. Or the inadequate phone calls I must make, having left home.

Lonnie Holley, Calling Mama, 2023, spray paint on paper, 30 x 22 ½ inches [photo: courtesy of UTA Artist Space, Atlanta]

I am in Birmingham as I write these words. After seeing Holley’s show, I visited the Chattahoochee Brick Company site in Northwest Atlanta, which is now owned by the City of Atlanta, and therefore no longer under the threat of development. I hope those whose remains exist there have found some rest. This trip, for me, has been funerary, in part because I have been paying my respects. The Eyes Were Always on Us was the wake. The Greyhound bus I rode to Birmingham the following morning felt processional. I scheduled my visit to Atlanta to coincide with the National Conference for Contemporary Cast Iron Art and Practices at Birmingham’s Sloss Furnaces. I was eager to visit because of who ran these furnaces, and who worked in the limestone, ore, and coal mines that supplied the foundry, which fed this town and US industry. These Black men and women gave their lives in the renovation of foreclosed Antebellum society. Much has been said about the legacy of exploitation Black Americans experienced there, specifically via the convict leasing system. The Birmingham furnaces supposedly only employed free men, but the ore, limestone, and coal naturally occurring in the northern Alabama area were mined by convict labor. But I didn’t hear anyone attending to that history, or its continuum. It’s difficult to see such a place reduced to a crust punk playground.

I try to reconcile this displacement of legacy—in the case of Sloss Furnace, posthumous gentrification by proletariat cosplay—by considering West African conceptions of passage and that, for my people, migration is an ontological condition. Katherine McKittrick writes in Demonic Grounds that “Black women, men, and children have been, forcefully and not, implicated in the uneven development of space because overarching traditional geographic projects require that they be placed and displaced. That is, black subjects have to ‘go’ and inhabit somewhere.” The very notion of a diaspora is contingent upon its diffusion. For the Ashanti, Fante, Igbo, Yoruba, and many others, the grave is a threshold from which one should never return. They all have some element of disorientation or deceit folded into the funeral service or procession to ensure that the individual does not linger in this realm.

Holley is a paragon of itinerate being, and through his use of the dispossessed object and image, he claims a disavowal. Salvage is a theoretical praxis for the artist; the wall is new ground, and he too is renovating foreclosed space to resituate site/sight. I appreciate these paintings greatly, and what it means to have them in Atlanta. I look forward to when and where Holley returns to turn the bones.

Lonnie Holley, The Eyes Were Always on Us, installation view, 2023 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the artist and UTA Artist Space, Atlanta]

Y. Malik Jalal’s maternal family is from Savannah, Georgia, where he was born in March of 1994. He received a

B.A. from Oglethorpe University in 2016 Jalal has spent almost a decade in the steel fabrication and forging.

Collage and assemblage are foundational to Jalal’s practice. Black culture, theory, ontology, and social

positionality, are the primary concerns and subjects within his work. Coming from a working class legacy and

upbringing, the context for his material engagement is labor and the home. Y. Malik Jalal works with black

family photos archives, predominantly with found or lost family photography. Jalal had a solo exhibition in

2019 at the Alabama Contemporary Art Center, and solos at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center and at

MARCH gallery in Manhattan. He has also curated a number of exhibitions for museums and private spaces.

Jalal has lived and worked in Atlanta most of his life, but is currently living and working in New Haven, and a

MFA candidate at the Yale School of Art.