Maria Sibylla Merian, Crocodile of Surinam. Illustration from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, 1719.

The Story of Art Without Men By Katy Hessel

Share:

Katy Hessel is seizing the moment. She is in the right time and place to elevate the power and presence of women in the field of art history. Her book The Story of Art Without Men (2023) is just one of her ambitious projects. Since 2015, when she discovered the absolute absence of women’s artworks at an art fair, Hessel has dedicated her labors to The Great Women Artists—not only through writing and curating, but also by posting daily discoveries on Instagram and releasing a weekly podcast episode.

Of course, Hessel is not the first to hold forth on the significance and vulnerability of women in the arts. She acknowledges straightaway that she is inspired by Linda Nochlin and other feminist art scholars. Published for the first time in the January 1971 ArtNews, Nochlin’s trenchant essay “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?” attributes women’s so-called failure in achieving the “greatness” enjoyed by their male counterparts to enduring strictures. Nochlin’s stark thesis was this: “The fact, dear sisters, is that there are no women equivalents for Michelangelo or Rembrandt, Delacroix or Cézanne, Picasso or Matisse, or even, in very recent times, for de Kooning or Warhol, any more than there are Black American equivalents for the same.”

The right conditions, Nochlin posits, must exist for any artist to reach a level of true greatness. “As we all know,” she writes, “things as they are and as they have been, in the arts as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male. The fault, dear brothers, lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education—education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals. The miracle is, in fact, that given the overwhelming odds against women, or blacks, that so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence, in those bailiwicks of white masculine prerogative like science, politics or the arts.”

More than 50 years later, the systemic social, educational, and institutional inequities that Nochlin identifies have come into play throughout every century of women’s art history—as recounted in Hessel’s Story of Art. Yet this book is no diatribe. It’s a full-bodied, exuberant exposé.

Hessel is clear in her mission. She writes, “this is not a definitive history—it would be an impossible task—but I am looking to break down the canon I have so often been confronted by in the culture in which I have grown up.”

Although the book covers the globe, the preponderance of stories within come from the US and the UK. The book offers an engaging art history that effectively “removes the clamour of men.” Hessel knows and acts on the fact that “women’s work” is to be touted. The full spectrum of art—from visionary to classic, quilts to sculpture, drawing to painting, performance to photography—is given the sincerest attention here. The author points, time and again, to the ways that women have persisted in learning and sharing techniques, creating art, and taking credit for their work as early as the 17th century. The author groups artists according to established movements—from the 1500s to the 2020s—and culminates with the latest developments in the field. Again and again, Hessel exposes women’s determined achievements. Among the most rewarding discoveries are child prodigies of the 1600s, artists reaching their creative pinnacle in their 80s, and accounts of pivoting practices.

Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait, 1630. Oil on canvas [courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC]

Hessel shows that the pressures successful women artists have placed upon themselves prove just as strong as the external forces that have established and sustained inequities in the field for centuries. She recounts cases of artists, even ones on the rise, who ceased artmaking abruptly once their perceived raison d’être disappeared. Lee Miller (1907–1977) is one example. Miller directed her professional arc from model to photographer to highly respected war correspondent, but post-traumatic stress after World War II led her to step away. She channeled her creative force into becoming a chef and mother. Miller’s son discovered her tremendous achievements in the field only after her death.

This book also spotlights stories of artists who experienced the radical shifts in nature, culture, and technology that accompany the turn of a century. The life and work of African American painter Alma Thomas (1891–1978) reflect such transformations. The first graduate in fine art from Howard University, she established an interracial gallery in Washington, DC, in 1943, and taught school for decades before returning to artmaking at age 60. Thomas became an accomplished abstractionist. In 1972, she saw her atmospheric paintings reach the upper strata of the art world with a solo exhibition at The Whitney Museum of American Art. In 2015, one of her paintings joined the White House art collection.

As Hessel notes, Thomas is not alone: “Progress is happening. This is thanks to a collective effort by actively engaged artists, art historians, scholars, and curators around the world …. It is their work that I am greatly indebted to, as without them it would have been impossible to write this book.”

Women’s art is steadily increasing in visibility and value today, but it still falls short of closing the gap created by centuries of bias favoring art made by men. Over more than three decades, I have personally researched, experienced, written, and podcast the stories of hundreds of contemporary women artists and curators. The work of Faith Ringgold, Carrie Mae Weems, Carolee Schneemann, Kara Walker, Cao Fei, Hito Steyerl, Amy Sherald, and Deborah Roberts and many others are illuminated in this book.

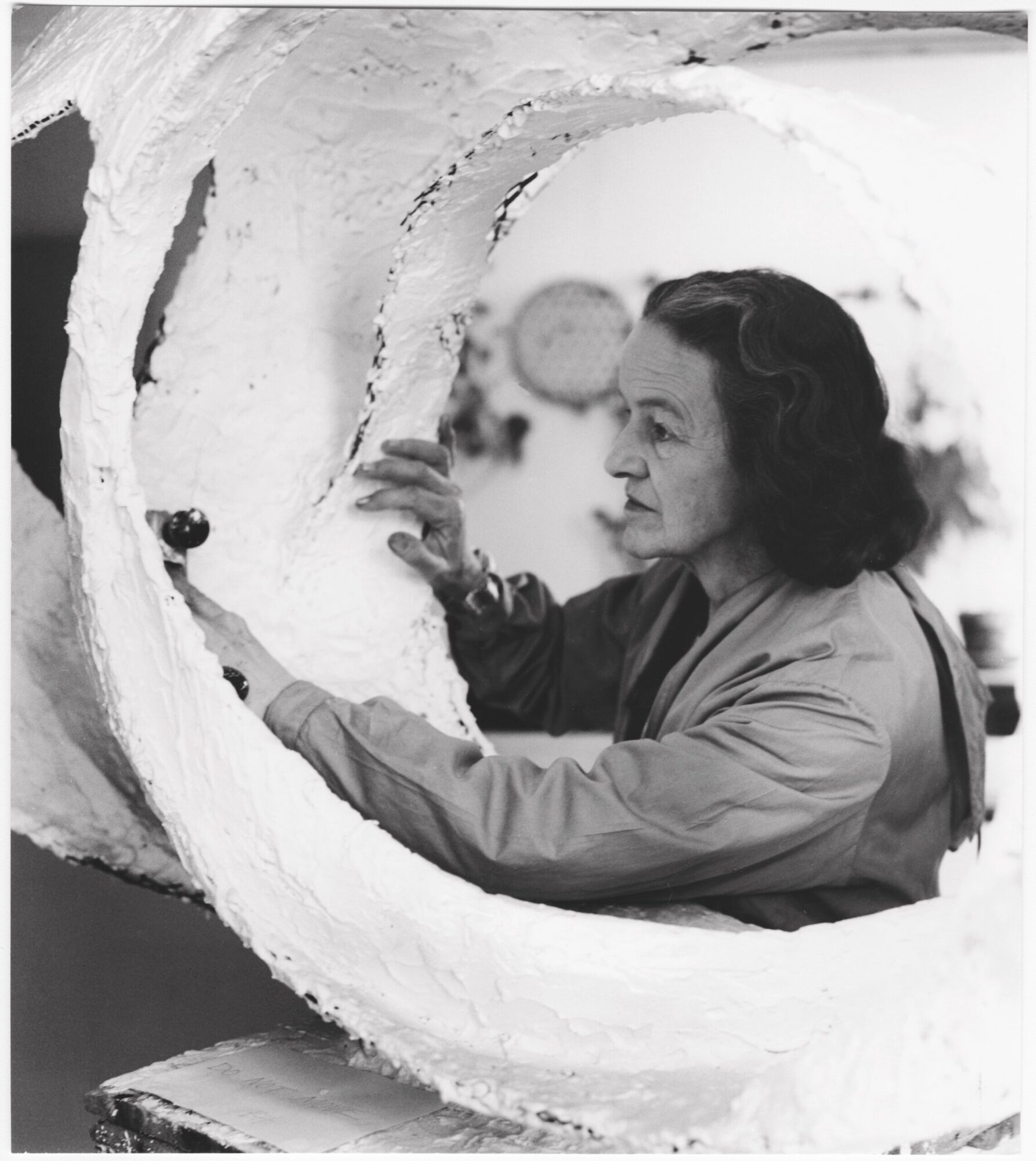

Val Wilmer, Barbara Hepworth at work on the plaster for Oval Form (Trezion), 1963, photograph. [copyright Bowness]

I explored The Story of Art Without Men in audio, digital, and print versions, and I found each form fresh and useful to my work. Certainly, I’ll remember and reference this publication for years to come, knowing that the need to center these stories, these issues, will not go away. I share Hessel’s conclusion: “Overlooked artists are not a trend. Women artists are not a trend. Queer artists are not a trend. Artists of color are not a trend. Art historians, and those engaged in creating the canons of art, must sustain their stories, and in order to do that—so future generations can see equality as normality and representation as priority—we must create useful, deeply engaging, thoughtful, accessible resources and institutions that reflect the new world.”

Cathy Byrd is an independent curator, art writer, and oral historian skilled in the art of roving. Her nomadic practice amplifies today’s issues and ideas at the center and the fringe of cultural scenes around the world. Her curatorial work includes The Blue Dress Project, Potentially Harmful: The Art of American Censorship, Re\constructing Atlanta, Le Flash and Losing Yourself in the 21st Century. Her writing appears in Art in America, Public Art Review, and Sculpture, among other publications. The Fresh Art International audio podcast she launched in 2011 holds an archive of more than 300 conversations on contemporary creativity. Find her at FreshArtInternational.com and @freshartintl