The Seventh Continent

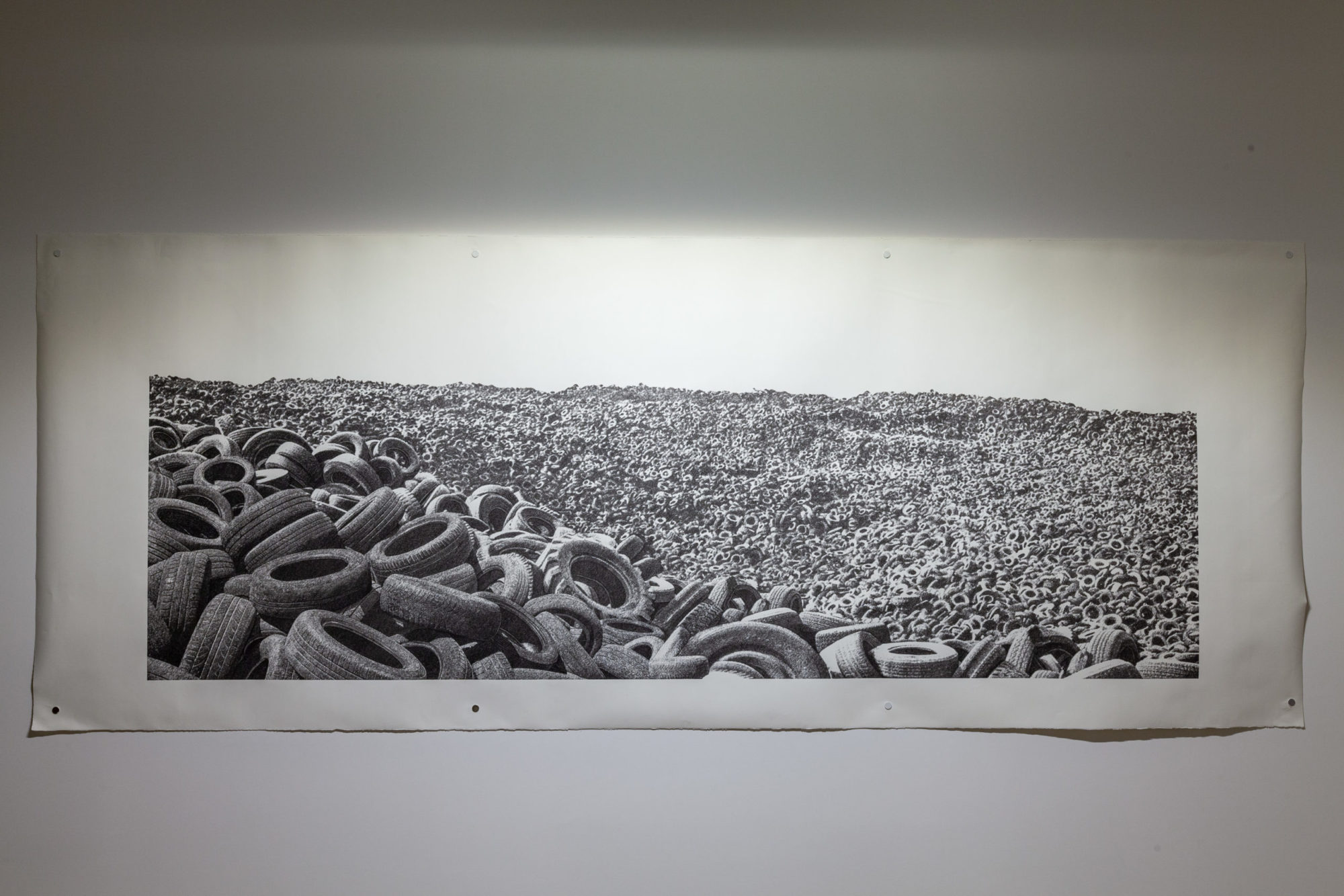

S’Madical, installation view, 2019 [photo: Sahir Ugur Eren; courtesy of the artist and 16th Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul]

“We are openly protesting 16th Istanbul Biennial. We reject all its supporters and participants. We demand everyone to protest against the biennial and to decline any sort of involvement” was written in a statement signed by more than 30 environmental protection and human rights organizations and activist groups active throughout Turkey and around the world. The statement was published in the Turkish art and theory magazine E-Skop shortly after the 16th Biennial’s opening.

Share:

The title The Seventh Continent refers to the Great Pacific garbage patch, which is a mass—approximately five times the size of Turkey—of mostly plastic waste from Asia, North America, and South America that is floating on the surface of the ocean. The biennial’s curator, Nicolas Bourriaud, describes this “new continent” as the “embodiment of the Anthropocene.” It formed quietly—a byproduct of global capitalism, mass production, and ignorance. Whereas sooner or later human beings inhabited all naturally formed continents, this one is largely being ignored. The patch’s enormous dimensions are evidence of the collective failure of governments and societies worldwide, and so, Bourriaud suggests it is time for artists to do an anthropological study of this human-made territory and explore new ways of living in the Anthropocene.

After the opening, a series of activist interventions took place. Some tried to keep visitors from entering the main venues, others distributed leaflets. All of them accused the organizers of hypocrisy because the biennial’s main financial sponsor was Koç Holding, the country’s largest industrial conglomerate, which owns gas and automobile industries in Turkey. The founding sponsor was Eczacıbaşı Holding, a company that built its fortune on exploitative gold mining in the 20th century. Other major sponsors deal in petroleum, gas, energy, cars, and other products that cause global warming rather than prevent it.1

The video Prospecting Ocean (2018) by Armin Linke was preceded by three years of research and field work. Through film and text, the artist scrutinizes the increase of industrial deep-sea mining that endangers oceanic ecologies. Linke makes the sources and production process of his work very clear; he names the sources of the texts and videos, and explains the applied methods of the deep-sea dives that were made possible through submarine drones and machines. This explicit examination of real events reveals how art can challenge conventional methods of knowledge production as manifested in politics, science, and journalism by presenting the results and the methods of research. Linke offers a work of art that sheds light on conventional methods of knowledge creation to stretch the limitations that fence in our thinking and behaviors.

The work was shown in the Yellow House, a neoclassical mansion that is part of the Anadolu Club facilities, and one of the six venues in Büyükada—the largest of the Princes Islands, located one hour by boat from the city center. The club was founded in 1926—supported by Kemal Atatürk—to strengthen the Anatolian national identity. Artworks by Linke and Ursula Mayer—who shows the video sculpture The Fire of Knowledge Burns to Ashes All Karma (2019)—were installed in the building without altering the imperial interior usually offered as a space for festive events, and which boasts a wide view of the Marmara Sea. The elderly club members in the garden sometimes looked up from their cards, startled by the flow of biennial guests rushing through the facilities—a co-existence which made it clear that this venue was appropriated from the locals rather than shared with them.

The Haliç shipyard in the Golden Horn harbor of Istanbul, which once belonged to the imperial arsenal of the Ottoman Empire, would have been the main venue, but it was canceled four weeks before the opening. The biennial’s organizers managed instead to install the work of 38 artists in the Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture, part of the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, a former warehouse at the waterfront of Istanbul’s hip Karaköy neighborhood. The upper floors of the four-story museum were open spaces for expansive installations, while the other floors were structured in separated rooms for solo presentations. In the clean postindustrial architecture of the freshly (yet not fully) renovated building, most of the works—regarding the artistic intentions and the representational strategies—appeared decontextualized, placed within the timelessness of the white cube.

For Turiya Magadlela’s installation S’Maidical’ (2019), however, the architecture worked particularly well. She covered the capsule in multiple layers of tapestries made from tights, which she sewed together live on site. The tights resemble various skin colors from “black to white.” They are seamed together at the waistline, such that a small hole between the legs remains with every single pair. The semicircular holes help the viewer to identify the fabric and indicate femaleness at the same time. Tights respond symbolically to the still enduring patriarchal fantasy that the female body should be pliant and obedient. Moreover, Magadlela challenges the sociostructural tendency to reduce women to what they wear.

Deniz Aktaş’s drawings The Ruins of Hope (2019) and Dora Budor’s unstable images (2019) in the Sculpture Museum re-invigorate the aesthetics of romanticism and reform its nostalgic dimension. Aktaş depicts a field of car tires or a heap of cable wires in the visual tradition of romantic landscape paintings. The drawings transfer the pre-industrial idea of men against nature, described at an early stage of capitalism, into the contemporary maxim of men against the Seventh Continent.

Budor created four glass cubes filled with fine dust, such as Origin III (Snow Storm) and Origin I (A Stag Drinking). Sounds of a construction site near the exhibition space are being recorded live. The sounds activate the aeration within the cubes, which causes fine movements of the particles. The exhibition catalogue mentions the J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) masterpiece Rain, Steam and Speed, which is perhaps the first (European) anthropogenic painting. Budor’s boxes do not reflect on machines conquering nature as does Turner’s painting but instead show the ongoing exploitation of lands and territories by humans.

Piotr Uklànski’s paintings were presented in the Pera Museum; the portraits mimic the aesthetics of white Muslim Tatar settlers as they appeared in Poland and Hungary since the 14th century, during the time of Ottoman colonization. Apart from the ridiculous poses of the depicted men and women, the painting style—such as the use of color—resembles another form of colonialism that is based on the cultural exportation of Western art. Uklànski adapts the virtuoso brush strokes of American postwar expressionists in Untitled (Félicité d’Arberg, Countess of Lobau) (2018), but he paints the male figure in the style of French realism. Not only do these portraits create awareness about the important and long-lasting influence of the Ottoman Empire in Europe, they also show how Western art is still colonizing styles of painting.

Many criticized the biennial for being disconnected from the political situation in Turkey. Coming from countries where freedom of expression is (still) a human right, such accusations overlook the fact that, at the moment, no other country has a higher number of imprisoned journalists than Turkey. Regime-critical art and activism or use of the heavily restricted Kurdish language increasingly lead to imprisonment in Turkey, at least since 2014, when Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became that nation’s president. The international art world had just begun to flourish again in Istanbul, after the biennial hit rock bottom during its 13th edition, curated by Fulya Erdemci in 2013, the year of the Gezi protests. Since the opening week the political situation in Turkey has worsened dramatically.

Glenn Ligon’s new works at the Mizzi Palace, however, pinpointed sociopolitical analogies between Turkey and the US. Ligon installed Setat Pakay’s documentary film James Baldwin: From Another Place (1970), which was shown for the first time in Turkey with Turkish subtitles. Baldwin lived in Istanbul, on and off, throughout the 1960s, as the city was a refuge for him from the turbulent times in his home country, which went through the most dynamic and violent years of the Civil Rights Movement. Today Istanbul finds itself in a state of political uncertainty, with revolution in the air. The wave of demonstrations, civil unrest, police and military riots in Turkey weakened the country’s international reputation and destabilized its economy. Tens of thousands of regime critics, hundreds of them artists, are still in jail, and the country’s political problems remained unsolved. Today’s Istanbul is slumbering, even as uncertainty and fear are in the air. The atmosphere of radical changes that “are” about to happen can be felt in Ligon’s new films Taksim (1) and Taksim (2). The films confront two possibilities for dealing with the city’s struggle, living in constant and eager anticipation versus carrying on. The two faces of Istanbul’s crisis are sensitively reflected through tense string music or exorbitantly vigorous jazz. As a metropolis that never sleeps, Istanbul is resting from violence, but haunted by rumors, restlessness, and fear.

The situation between Turkey and the United States has reversed since the 1960s. Ece Temelkuran, a renowned Turkish journalist, sees more similarities than differences between Erdoğan and Donald Trump. Since 2016 several crimes and unconstitutional statements and actions of the American president have shown that his power is being exercised in defiance of the law and the American Constitution, a critique applicable to many of the world’s leaders at the moment. Declaring Turkey as one of some instable countries implies that other democracies are still fully functioning. Ligon’s work does not produce political polarities; rather, it reflects the fragility of local societies in a globalized world.

If the biennial is not risky enough, it is because the curator carefully followed his mission statement and created a show that evokes—if not in its full integrity, given the immoral sponsors—a strong response to things we already know but have not yet managed to understand: our world does not save itself.

Teresa Retzer studied art history and philosophy in Vienna, Siena and Zurich. Her research focuses upon contemporary art practices and media theory that engage with the influence of digital infrastructures on society. She presented her research at international conferences and wrote scientific texts for catalogues and journals. She wrote art criticism for several art magazines, including “Mousse Magazine,” and “Spike Art Quarterly.” Retzer interprets art writing as possibility to engage with sociopolitical problems, and apart from academic texts on art, she concentrates on right-wing extremist subcultures in former East Germany. Currently she is working on her PhD project, which interrogates new forms of knowledge production in contemporary art and curatorial practices.

References

| ↑1 | Translated from E-Skop: “Another promoter, Anadolu Efes, belongs to a group of investors that tried to build a coal power plant directly at the Black Sea, close to the city of Gerze; the local inhabitants’ strong resistance, however, prohibited its realization. Further, the LPG company Aygaz and the petroleum dealer Opet, both in big parts owned by Koç group, and the petroleum refinery Tüpraş, belong to the biennial’s sponsors. Some other contributors include İçdaş Energy, which builds thermal power plants in the Dardanelles Strait, and airline companies such as TAV and the Turkey-based shares of the automobile company Ford.” See https://www.e-skop.com/skopbulten/bienal-protestosu/123 |

|---|