The Role of Art Criticism in the Community

Share:

This essay was originally published in ART PAPERS November/Decmber 1990, Vol 14, Issue 6.

It was the scariest morning of my life. The critic, the academic, the nice Jewish boy from the Bronx, was going to get arrested, on purpose—and at a national AIDS demonstration no less. My grandparents would be rolling in their graves. My parents, if they were to spot me on national TV, would put me in my grave. And worse, if the L.A. Times, the paper for which I wrote most frequently, ever found out, I’d probably be banished from my computer pod, never mind being disqualified from writing about the two areas I cover—art and AIDS.

Why bother at all, considering how unhinged I was about confronting the Chicago police, not exactly known for their empathy for activist causes. I had reason for sticking my neck out. At the time, I was involved in an analysis of street theater and direct action as art spectacle. I focused on a group with which many of you may now be familiar—the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP. It’s a grassroots AIDS movement that seeks to end the AIDS crisis through direct action, civil disobedience, and discussions with policy makers.

What interested me most, though, was ACT UP’s artistic panache—the use of graphic images and dramatic spectacle to reconstruct presumptions and outright lies surrounding the ten year old epidemic often put forward by the dominant media. To ACT UP members, the mainstream notion that AIDS was spread on purpose by promiscuous gays, crack-crazed minorities, and proselytizing I.V. drug users had to be challenged by the alternative notion that government, due to its ingrained homophobia, racism and sexism, had failed miserably in its responsibility to educate candidly and promptly about the risks everyone faces. It had been up to the gay community, and not health institutions, to reduce the rate of new infection in the mid- 80s to less than one percent in that community.

Undisguised propaganda was seen by ACT UP’s early members—many of whom were graphic designers, TV producers, and theater people—as an effective arsenal against society’s unintentional (and intentional) homophobia and AIDS denial, and it became its handmaiden. Academic (and eurocentric) distinctions between the audience and the actors, legitimate theater and street theater, folk art and fine art, were canned. How impressive. To me, this represented a self-conscious attempt to breathe new life into a postmodern eating its own tail. It made artists into citizen diplomats—high powered players in American politics. The greater the artistry, the greater the impact to effect change. It returned art to its primal function as ritual and as war cry and as a means by which people keep a culture alive and healthy. I wanted to know as much about the strategies of this activist art as possible.

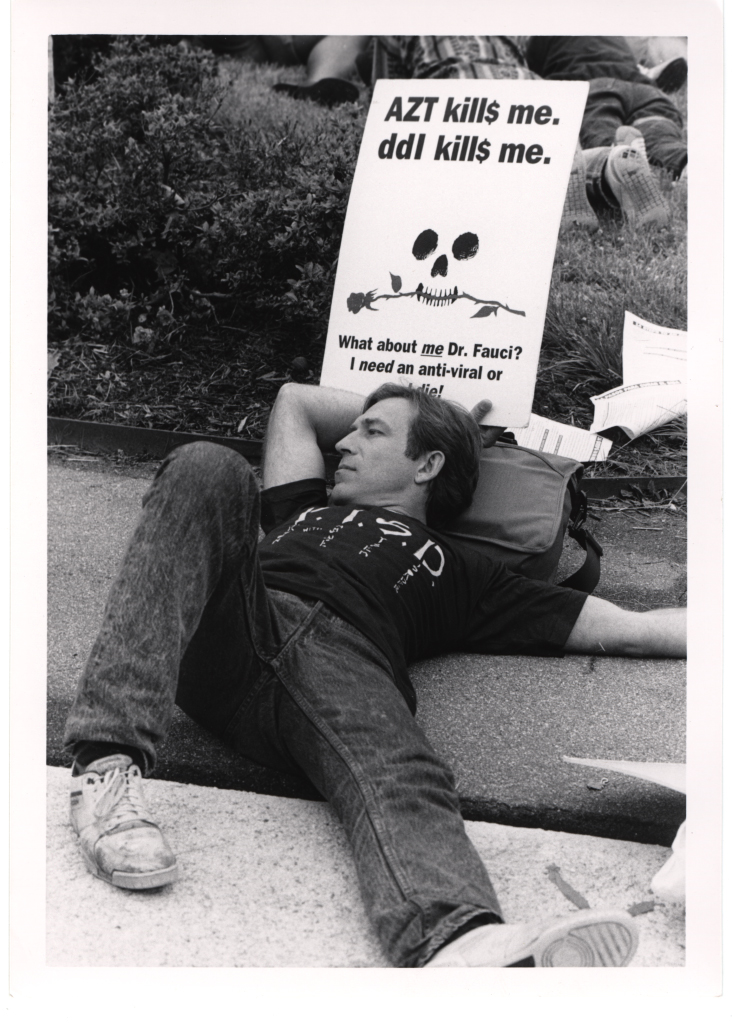

Some of these strategies entailed creating public disturbances, albeit with style. I’ll briefly sketch for you three examples. “The Wall Street Action” had seven men dressed as bond traders entering the New York Stock Exchange using fake name tags. Five chained themselves to bannisters, and just as the opening bell went off, dropped a banner that said SELL WELLCOME (the manufacturer of the AIDS drug AZT); others blew fog horns. They disrupted trading for five minutes—a historic first—to call attention to the corporate greed that makes mindless profits from AIDS drugs. During the March 1989 New York City mayoral campaign, artists designed a mock newspaper called the New York Crimes, and inserted copies in genuine Times stands in Wall Street. Meanwhile, thousands of activists surrounded City Hall, calling for New York City to dump the current mayor at that time, Ed Koch. Koch was pictured with the text, “10,000 New York City AIDS Deaths,” followed by a favorite line of his, “How’m I doin’?” Last year, ACT UP literally made a spectacle of itself outside of New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral, targeting John Cardinal O’Connor for his refusal to validate safer sex practices as a way to contain the epidemic (30,000 cases of AIDS have ravaged that city). Some ACT UP members, themselves Catholics, took their ire inside the Church to the mass, blurring lines between critics, artists, and activists to call attention to their cause.

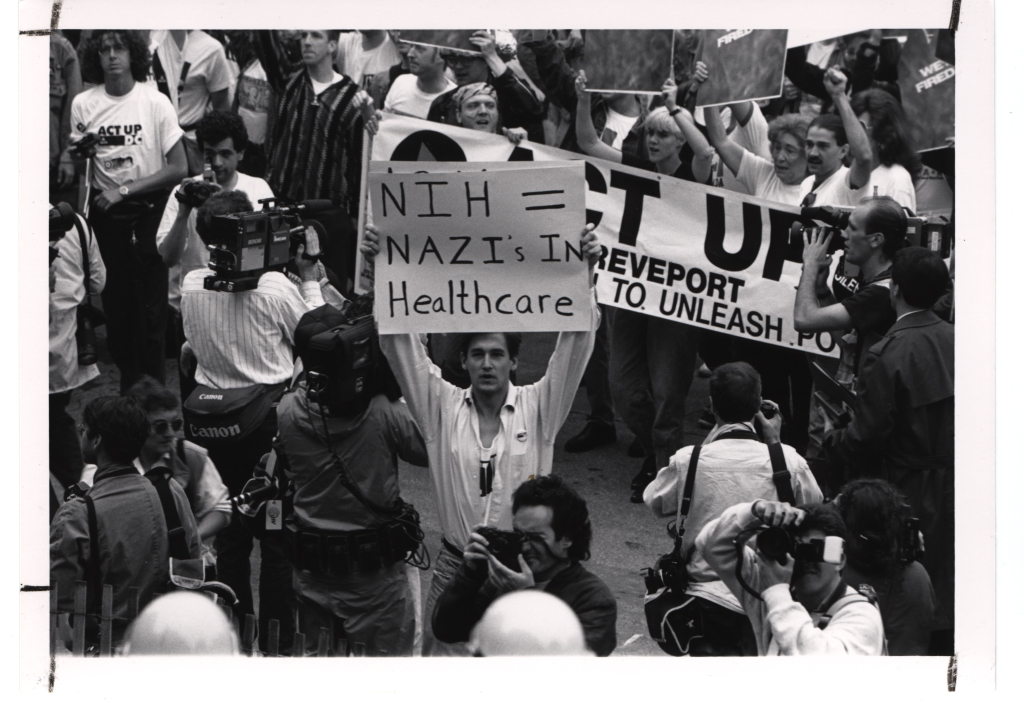

Protestor outside National Institute of Health, 1990 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

But I’m not so interested here in talking about dissolving distinctions between art and life as much as I’m more concerned about dissolving distinctions inside, within one’s heart and soul. My interest in spectacle as political action had to do with a growing realization that I was becoming an activist myself, whether I liked it or not, and that the spectacles and graphic images I observed had the effect of moving me. The more I stood on the sidelines, applying my education and critic’s gaze to this revitalized form of street theater, the more I realized that my place as critic had become obsolete that even the TV cameras presiding everywhere were the main players in the social drama, egging the activists on, and that there was no place for distance in this game unless you weren’t interested in hearing the activists’ pain, unless you were on Jesse Helms’ side.

I’m a gay man who has witnessed a lot of death in the last years. I was growing angrier by the day the more it became apparent that polite discussions with policy makers weren’t accomplishing anything, that gays, people of color, artists, etc., were a liability to advocate on behalf of, that the only thing that would make American institutions stop passing the AIDS, art, abortion buck was if these institutions grew scared of the activists, if the activists could demonstrate at least as much skill in organizing their constituencies as the Christian Right had.

So standing on the sidelines, I began to find my role as objective critic irrelevant, especially as I witnessed my boyfriend getting violently dragged away by the police, especially as my closest women colleagues got clubbed on the head for passive resistance. My ability to write well about the social and artistic conditions of my time was clouded by this odd and artificial American distinction between doers and onlookers, artists and critics, heroes and historians that I had internalized all too well, a distinction I think that robs those who embody one discipline over a multiplicity of them the mobility most of our personalities require.

I come from a tradition—a Jewish tradition—that tells me that the greatest possible good is the ability to practice one’s culture with as little repression as possible, that peace and justice are not meant for heaven, but are worldly necessities that must be fought for now, that silence about injustice is the equivalent of being complicit in it, that people will be put in gas chambers much faster for their passivity than for their visibility. The notion that the world could and should be different than it is now has deep roots within my tradition. While much of American Jewry has abandoned the radical transformative vision for the sake of fitting into America’s dominant conservatism, the legacy lives in me, and is the reason, I believe, that I became a writer and a critic. In fact, the anger that comes from spotting wrongs that could so easily be righted is the only kind of creativity I have ever felt in my life. Had I had a different kind of upbringing, one that emphasized Dionysian impulses rather than Apollonian qualities, I’m sure I would have been an artist.

Perhaps I am already and just don’t know it. Getting arrested had the effect of changing many of my ideas about who I am, disrupting once and for all this crazy notion that one sees things better from a distance. Transforming one’s life, or at least one’s thoughts, seems to me to be key purpose of art. When I view a good performance, I am reminded that art provides us with an experience no other form can because of the way it throws some shrapnel in our emotional, unconscious and collective lives in unfathomable, but irremediable, ways.

I remember feeling this very mystery while running like a banshee through the Chicago streets, passing thousands of ranting, singing, chanting AIDS activists and their graphics, being led by someone who turned out to be much more radical than I would have liked. In the climax of the drama, I recall that we did have a goal—to arrive at the Prudential Life headquarters building in Chicago and block the entrance until the police came. But a line of police and their horses blocked us. What to do? “Charge,” my activist buddy yelled. And so we did. Only to be promptly arrested and carted away so fast that I couldn’t tell you why I was ever so very scared to begin with.

Or maybe I can. Getting arrested isn’t scary, testing your own limits is. Crossing an uncharted road, feeling passionately about an unpopular subject, taking a chance in your life—that’s what’s scary. The real policemen, I’ve learned, the real taskmasters of the psychic concentration camps, live not on the outside, but on the inside. If they are American, they can be very militant and they often raise strong defenses about crossing boundaries, especially if they are critics. “It would be conflict of interest.” “My boss would fire me.” “I don’t want to lose my objectivity.” “I don’t have the constitution for it.” “Writing is plenty activism.” “Social involvement is only for the underclasses.” I’m not saying that all critics should abandon the tools of their trade and start making dance-based performance pieces or marching in demon- strations (although maybe those are not such terribly inappropriate exercises for someone who makes a career writing about them). Of course, each critic needs to decide for him or herself what the potential risks of participation are. But I also believe that the rejection of moral neutrality in a world growing as complex as ours makes possible a deeper understanding of the dynamics of culture and society. In other words, moral neutrality and objective distance may be obsolete and irrelevant, if not self-destructive, values in a country that’s responded to freedom in Eastern Europe by growing more repressive.

ACT UP’s NIH demonstration on May 21, 1990 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Why obsolete? It seems, in the end, that we do live in a multi-cultural, multi-genderal, mestizo, crazy America. Like it or not, the polyglot nature of this place won’t go quietly away, and it will present only greater challenges to our critical thinking in times to come. Last month, we in L.A. were treated to a Los Angeles Festival, organized by Peter Sellars. It featured dance and ritual from Pacific Rim countries, many of whose native people have settled in L.A. Each culture defied us to use our western criteria of quality and taste, content and form, to lasso their sacred traditions. The cultural free-for-all had the effect of teaching many of us that criticism can be a great mechanism for creating aperture and context, just as it can also provide a formidable defense against accepting change. But you had to get your hands dirty—you had to talk to the artists and try and see yourself from their eyes, you had to throw yourself into the drumming and shouting and refuse your tourist card. Like participating in the AIDS demo, it solidified the central idea that I wish to communicate here: that it is precisely in the process of acting to transform the world that the world reveals its deeper structures and meanings to us—it is not the other way around, as most critics believe, it is not merely by theorizing.

In closing, I think that we as critics have a particular gift of amassing information, analyzing it, placing it within context and exposing false mythologies. There are ways of being creative with those tools. Last spring, a group of culturally diverse critics and I decided to research and analyze the meanings behind the Jewish feast known as the Passover Seder—which is a meal and a ritual that recounts the story of the exodus from Egypt—as an impetus to acknowledge the oppression of all peoples. We invited black, Latino, gay, Arab, Asian, and Native American artists to participate in our process by sharing with us their ancient liberation stories. We produced a book on our research. The ritual itself lasted four hours and proved both an educating and spiritualizing link between various groups of artists in L.A., proof that artists and critics have the power to put careerism and competitiveness aside and become activists for world glasnost every now and then.

I believe very much in this new vocation for the critic. As the art world faces attack from people scared of the art community’s new political voice—the same people who are scared of affirmative action, bilingual education, black civil rights, gay and lesbian visibility—it seems in our best interest to live up to our true potential as alternative chroniclers who occupy an important role in that chronicle. It’s a way of restoring our own faith in criticism as a natural, and perhaps, even holy act that ties the community together in new and challenging ways. It may be shocking to everyone around us—no less to ourselves—if we start looking like artists or activists, but I wonder if each of us doesn’t feel a responsibility to live up to the challenges. Why else would we have been attracted to our work, if not challenge the primacy of the hats we wear? I’d like to end with quote from a lesbian critic, Judy Grahn, who’s spent thirty years of her life excavating an ancient gay and lesbian legacy, and then went on to write poetry about her discoveries: “…organizing autonomously for their rights and history and cultural traditions and rightful place in society is all that people ever have, that this is the weapon, territory, nation, power. All the rest is despair, the whining of dogs who cannot speak, except to beg for bones.”

Dr. Douglas Sadownick was a critic, fiction writer and AIDS activist. He wrote for the L.A. Times, The L.A. Weekly, Outweek, High Performance, The Advocate, L.A. Style, and Elle.

In 2005, Dr. Sadownick founded the nation’s first LGBT Specialization in Clinical Psychology at Antioch University. He currently works as a clinical supervisor and teacher in West Hollywood. He is also the author of several books including Sacred Lips of the Bronx (1994), Sex Between Men (1997), and How and Why to Find a Therapist (2024).