The Political Afterlife of the Babri Masjid

Vivan Sundaram, Burial: Iron Pyre, 1993, pigment print. nails, iron vitrine, 74 x 101 centimeters [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

On August 5, 2020, a digital billboard in New York’s Times Square flashed with images that may have been unfamiliar to the average passerby. Depicting the Hindu deity Lord Ram and digital renderings of a temple dedicated in his name, the billboard would have perhaps felt more incongruous among the surrounding retail and luxury goods advertisements but for its bright, lurid colors signaling some sense of yet another product for sale in the commercial center.

Sponsored by Jagdish Sewhani, president of the American India Public Affairs Committee—a US-based fundraising organization in support of the ruling right-wing—the billboards were a declaration of victory. On that same day in August, thousands of miles away, in the north Indian city of Ayodhya, Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone for the Ram Mandir. He triumphantly announced that the temple would induce new economic opportunities and function as a symbol of the nation’s spirit: “We have to join stones for construction of Ram Temple with mutual love, [and] brotherhood.”

For members of the Indian diaspora who gathered in New York to protest this most recent iteration of state-sanctioned Hindu fundamentalism, the remarks cut a vicious irony, reopening the wounds of communal violence that reached a fever pitch almost three decades ago, when on December 6, 1992, scores of frenzied Hindu extremists, encouraged by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)—a paramilitary volunteer organization—and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP or World Hindu Association), demolished the Babri Masjid, a 16th-century edifice in Ayodhya. These extremist groups mobilized militant anti-Muslim and nativist rhetoric to claim that the site of the Babri Masjid had been the birthplace of Lord Rama, and the site of a medieval Vaishnavite temple that had purportedly been razed by Muslims. A violent conflict ensued in Ayodhya, which sparked riots in cities across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The violence was particularly horrific in Bombay. Overall, an estimated 2,000 Indians were killed in the riots.

Unknown, Babri Masjid, Faizabad, about 1863–1887, albumen silver print, 6 × 8 1/4 inches, 84.XA.417.32 [courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles]

Both the destruction of the Babri Masjid and recent consecration of the Rama Temple at Ayodhya testify that in India, as elsewhere, monuments mark neither the culmination nor beginning of a history, but rather act as a flashpoint demonstrating the contested nature of the past within the present. In India, which boasts a constitution that explicitly defines the nation as secular, such monuments also attest to historicity—the actuality of real-world historical events—as being inseparable from mythology. Such a complex notion of historicity’s function, as historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta has written, sparked fierce debates between Hindu nationalists and opposing camps of secular liberal and leftist historians, politicians, critics, and artists about how art history and archaeology ought to function within civil society in the wake of their co-optation by the Hindu nationalist (or Hindutva, as it is known in India) agenda.

For two decades since its founding in 1989, the Delhi-based Sahmat Collective, a network of artists, curators, playwrights, and critics, led cultural practitioners in resistance against the rise of Hindutva. Through public poster projects, participatory performance campaigns, exhibitions, and activist demonstrations, the collective, whose members included the influential critic and curator Geeta Kapur and the artist Vivan Sundaram, mounted a counternarrative of leftist resistance to the encroachment of Hindutva and the neoliberal politics engendered by globalization in India at the turn of the 20th century. Recent scholarship on the critical legacy and history of the collective by Saloni Mathur and by Arindam Dutta—as well as an internationally traveling exhibition dedicated to Sahmat in 2013—illuminated the tumultuous atmosphere of art and activism in 1990s India for a wider global audience. Sahmat’s swift and direct response to the 1992–1993 Ayodhya riots, in particular, demonstrates that the group’s activism was informed by a nuanced understanding of how history could be mobilized against secular values. It also offers a model for critical resistance against authoritarianism today.

The formation of the Sahmat Collective in 1989 was propelled by one particular event alongside an emerging tendency toward right-wing Hindu fundamentalism. On New Year’s Day 1989, the playwright Safdar Hashmi and members of his street theater troupe Jan Natya Manch (People’s Theater Front), a cultural front of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), were attacked by a mob in central Delhi. Hashmi and his troupe had been vocal supporters of labor strikes to advocate for increases in minimum wage, drawing tensions with local industry leaders and politicians. Hashmi suffered severe blows to the head and died the next day, prompting protests, marches, and processions throughout Delhi. By the first week of February 1989, protests in support of Hashmi had erupted across India, and meetings of cultural activists had coalesced into the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust, mobilized by a need to develop a forum for concerted resistance efforts and buoyed by the collective’s commitment to leftist principles and a desire to remain independent.

Foreground: Vivan Sundaram, Memorial: Burial, 1993, all works mixed media including iron and glass vitrine, iron nails, and black- and-white photographs [photo: Hoshi Jal, Times of India, Bombay, February 23, 1993; courtesy of the artist]

Nalini Malani, Unity in Diversity, 2003, video, 7 minutes, 30 seconds, installation view, The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2013 [collection of Walsh Gallery archives; courtesy of Smart Museum of Art, Chicago]

Later in 1989 a Hindu fundamentalist movement spearheaded by the VHP, with support from the BJP, launched a national campaign to reclaim Ayodhya as the site of Lord Rama’s birth and advocated for the destruction of the Babri Masjid, which had been built in approximately 1528, at the behest of the Muslim ruler Babur. Historians generally agree that competing claims to the site by Hindus and Muslims began in the mid-19th century, under British rule, with colonial administrators partitioning the masjid’s compound between Hindus and Muslims and allowing each group to worship. In 1949, two years after independence from colonial rule, an infant idol of Rama was surreptitiously placed inside the masjid. The state court decided to lock the doors of the compound permanently to the public, though crucially, Hindu priests were allowed to continue regular ritual prayers to the Rama idol. In February 1986 government officials decided to open the doors of the Babri Masjid to give Hindu pilgrims and worshippers access to the Rama shrine. This concession to the increased efforts of Hindu activists to declare the Babri Masjid site as the birthplace of Ram marked a crucial turning point that prefigured the Ayodhya riots.

In 1991, as Hindutva gained political traction at the national level with monthlong yatras, or religious processions, led by BJP leaders, Sahmat responded with political actions in support of secularist ideals by launching the Artists Against Communalism (AAC) campaign on the second anniversary of the attack on Hashmi. Sahmat staged sit-ins, performances, and programs at cultural sites in major Indian cities. Later that year, more than 400 painters, writers, and photographers participated in the exhibition Images and Words, which was part of the AAC campaign, and toured 30 cities and dozens of schools in Delhi. In August 1993 the collective presented Hum Sab Ayodhya (We Are All Ayodhya) simultaneously, in 16 cities, across India. The exhibition included photographs, prints, and architectural drawings by more than two dozen artists who attested to Ayodhya’s rich history of cultural and religious diversity, highlighting the traditions of Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, and Jain sects in the region. When the exhibition was shown in Ayodhya, it was torn down by RSS and BJP coalition members opposed to the contents of a text panel with Jain and Buddhist references. Sahmat was charged by the state court with intent to cause riots and promoting communalism, and technically designated as a criminal organization.

As Geeta Kapur reflected in the 1993 Sahmat Bulletin, the aim of the Hum Sub Ayodhya exhibition was largely didactic, functioning as a pedagogical exercise on secular grounds, a battle for maintaining “the freedom to transmit knowledge as a foundation of that more controversial issue of the freedom of expression.” Sahmat refused to limit its activities solely to the communities to which the collective’s members belonged, and instead it addressed wider publics in the form of educational and artistic programs. In doing so, Sahmat directed its audiences to question the state’s capacity to rewrite national history rather than merely questioning how history manifests in cultural production. What was at stake in the destruction of the Babri Masjid was not only the material ruins as historical monument, but the outcome of numerous legal battles over archaeology and its role in providing scientific evidence.

Vivan Sundaram, Memorial, 2004, installation view [courtesy of the artist]

As Guha-Thakurta details, such legal battles conscripted the hamstrung civil servants of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). These civil servants faced increased state pressure to conduct excavations at the site and thus corroborate claims that there was, indeed, beneath the Babri Masjid, a Hindu temple that had been razed by Muslims. Compromised Western and Indian archaeologists, who feared losing their professional licenses to conduct excavations, were thus obliged to cooperate. They produced evidence—in the form of a set of carved sculptures and column bases—to affirm state belief, thereby demonstrating the limits of archaeology to serve as an objective, scientific field in a nation where historicity was besieged by mythology. Proof of this siege could be seen in the marshaling of scripture and literary evidence alongside forensic studies in the court battles.

The limits of documentary evidence to serve secular purposes in India’s court system became a viable means of artistic innovation. Vivan Sundaram’s room-sized installation Memorial (1993–2014) made use of the documentary photograph as a starting point for excavating the pressurized atmosphere of communal violence under the BJP’s rule. As Andreas Huyssen notes, Sundaram was part of a group of artists whose work “articulates memory as a displacing of past into present,” without relying upon the “delusion of authenticity or pure presence.” Seven constituent parts radiate from a photograph taken by journalist Hoshi Jal and published in the Times of India. The picture shows an unnamed Muslim man lying dead on the street in the aftermath of the Ayodhya riots. Memorial functions as a mourning device, as alluded to by its title, and as a counter-monument to the Babri Masjid—one that recuperates the anonymous figure within a kaleidoscopic view of a society fractured by sectarian violence.

Although Memorial resonates with other memorials to anonymous figures, such as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, Sundaram’s installation reveals the internal contradictions of the nation itself rather than celebrating national service. The artist’s manipulations and additions to the installation over two decades mark the temporal onslaught and increasing factionalization of the Indian nation. But even in its initial installation, Sundaram was always careful to situate the photograph as the evidentiary starting point for the work’s lacerating critiques of Hindutva. For Mausoleum, Sundaram produced a life-size plaster replica of the prone figure set within a triangular Plexiglas and iron frame; in Burial, the artist displayed various monochrome prints of the original photograph, each pierced by hundreds of tiny iron nails, within six small vitrines placed at eye level. Gateway comprised numerous tin suitcases stacked to resemble the monumental arches found in India’s major cities, including the famed Gateway of India in Mumbai. One such trunk lay open, as a coffin would be, to reveal blue neon letters spelling out fallen mortal. Such a plain-faced statement, by reducing the tragedy of sectarian violence to a mere signpost of one of its disastrous effects, offers a bold counterpoint to the vicious actions of state-sanctioned violence and provides what monuments themselves cannot. Through a radical reduction of form and a heightened awareness of history, this counter-monument honors the complexity of India’s ever-shifting present by memorializing eternal loss.

Vivan Sundaram, Gateway, 1993, tin trunks, neon sign, 231 x 216 x 84 centimeters [photo: Gireesh G.V.; courtesy of the artist]

In the almost three decades since the destruction of the Babri Masjid at Ayodhya, several cases against the militant Hindu factions that instigated communalist violence have been lodged at various high courts across India. More than 300 people were deposed in such proceedings, and 17 of the accused died over the course of the trials. In November 2019 the Indian Supreme Court ruled that the destruction of the Babri Masjid violated national laws. But the body also ruled that a trust was to be created to build the Ram Mandir temple on the site of the former masjid and granted a plot of land for the construction of a nearby masjid in Ayodhya. On September 30, 2020, all 32 parties accused of instigating the violence at Ayodhya were acquitted, calcifying for some the BJP’s dominance as a Hindu majority party.

What conclusions can be drawn from such blows to the promise of secularism in what is often touted as the world’s largest democracy? In a recent interview with Saloni Mathur, Geeta Kapur commented on the 2019 re-election of the BJP, noting that the rightward shift of nations is exacerbated and enabled by the flows of global capital and underwritten by corporate interests, but it is upon the very ground of the nation that these forces can and must be resisted—echoing Kapur’s assertions some two decades ago that the fight against authoritarianism must be fought from all sides. To consider the lasting influence of monuments, their relevance, their effects, and their futures, it is essential to resist nationalist and authoritarian assertions that monuments prescribe national history. Caught between the moment of their construction and the past to which they allude, monuments denote history in flux. Through the resistance modeled by artists who collectively work against the state’s attempt to define monuments, we can move the dial of history ever forward toward progress.

***

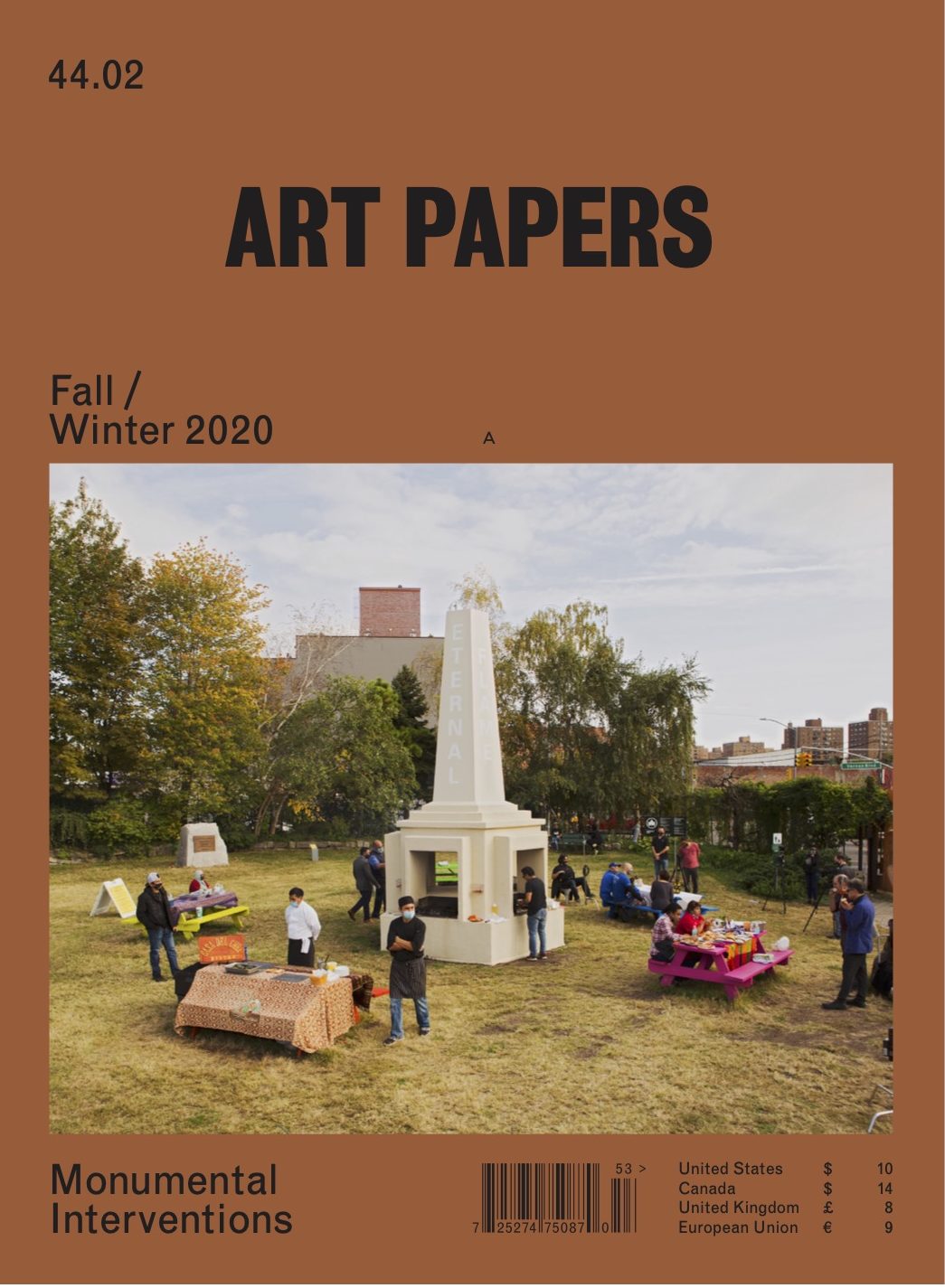

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Fall/Winter 2020 // Monumental Interventions.