The Museum Union Wave

Share:

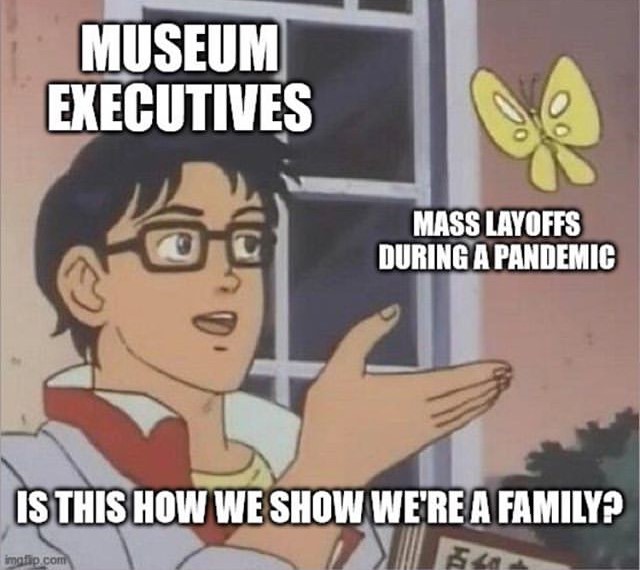

By spring of 2019, museums across the United States had become what labor organizers call “hot shops.” Workers were fed up and ready to do something about it. No one could remember a time when wages for work in the arts met the cost of living in an American city. Many museums, meanwhile, were increasing their endowments and making huge real estate investments. Executives were drawing six- and seven-figure salaries, and frontline workers were making minimum wage.

New demands for accountability had arisen in the institutional art world. Almost two years had passed since the first allegations that Knight Landesman, onetime co-publisher of Artforum, had sexually harassed many women, including staff members. At the New Museum, workers began to organize after attending a workshop the museum hosted as part of its Sexual Harassment in the Cultural Sector series. At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, management’s inadequate response to abuse allegations got workers talking across different departments about common grievances.

Many art workers were insisting that institutions take seriously the political provocations hanging in their galleries. This scrutiny extended to donors and boards of trustees. Actions by P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) had forced the Guggenheim and the American Museum of Natural History to announce they would decline any future gifts from the Sacklers, the family that brought us Oxycontin and the opioid epidemic. In the following months, protests would successfully drive board members from their seats at the Whitney Museum and The Shed.

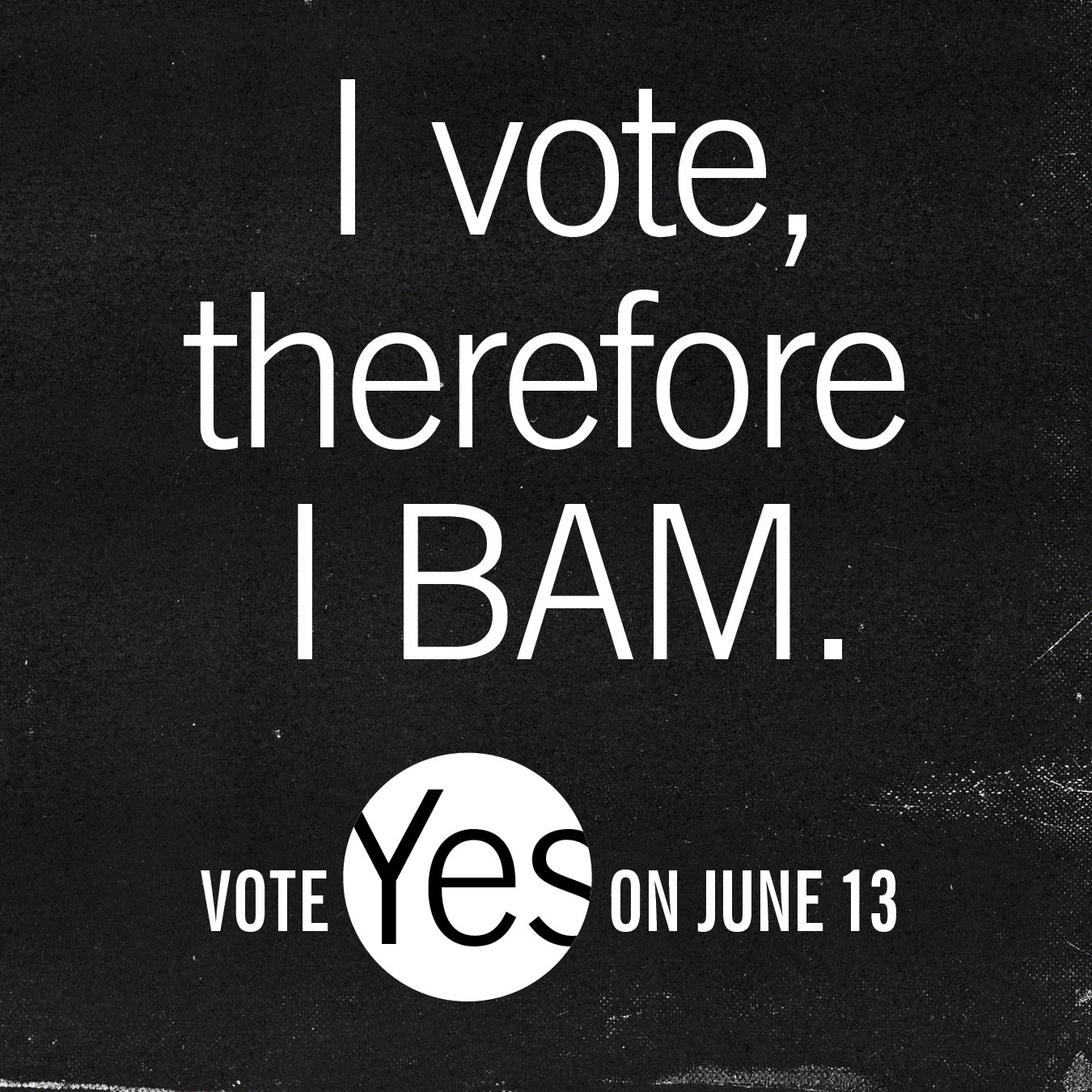

The previous 12 months had brought tumultuous contract negotiations at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), and the Vancouver Art Gallery, where public pressure campaigns—and, in the last case, a strike—won significant victories for long-standing unions. Workers at several institutions in New York had already begun to unionize at the vanguard of what would become a nationwide movement. Workers at MoMA advised workers at the New Museum, who in turn supported workers at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) and the Tenement Museum, everywhere demystifying the process of organizing and creating cross-institutional solidarity.

The president’s executive orders, his appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), and the Supreme Court’s Janus decision had contributed to a backward ebb, in which labor organizing became all the more difficult. Still, there had been a wave of teacher strikes, as well as some successes in the Fight for $15 movement at state and local levels. Around the country, popular approval of unions appeared to be on the rise.

Into this charged atmosphere came a spreadsheet. “Art/Museum Salary Transparency 2019” encouraged museum workers to anonymously share their salaries. Its creators, workers at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, took inspiration from curator Kimberly Drew’s own salary-share during the American Association of Museums 2019 Annual Meeting & Museum Expo just 10 days earlier. The broad inequities within arts institutions were no secret, but soon thousands of entries made them impossible to ignore.

Scene Break

Every union begins with a conversation among workers. Commiseration can turn to the conviction of a shared purpose. Drinks after work and whispers in the hall become secret meetings and the drafting of demands. Unions typically fight for wage increases and benefits, but SFMOMA workers also wanted a less restrictive dress code for frontline staff. At the Guggenheim, they are demanding safe working conditions for art handlers. At the New Museum, the union won the right to make an annual presentation to a subcommittee of the board of trustees.

After the difficult task of building consensus, workers usually contact an existing union to support them, collect signed authorization cards, and file for an election. Once they vote to form a union, however, the fight has just begun. Next, they must bargain for a contract and enforce its terms. All of this labor is unpaid, and management typically fights the workers every step of the way.

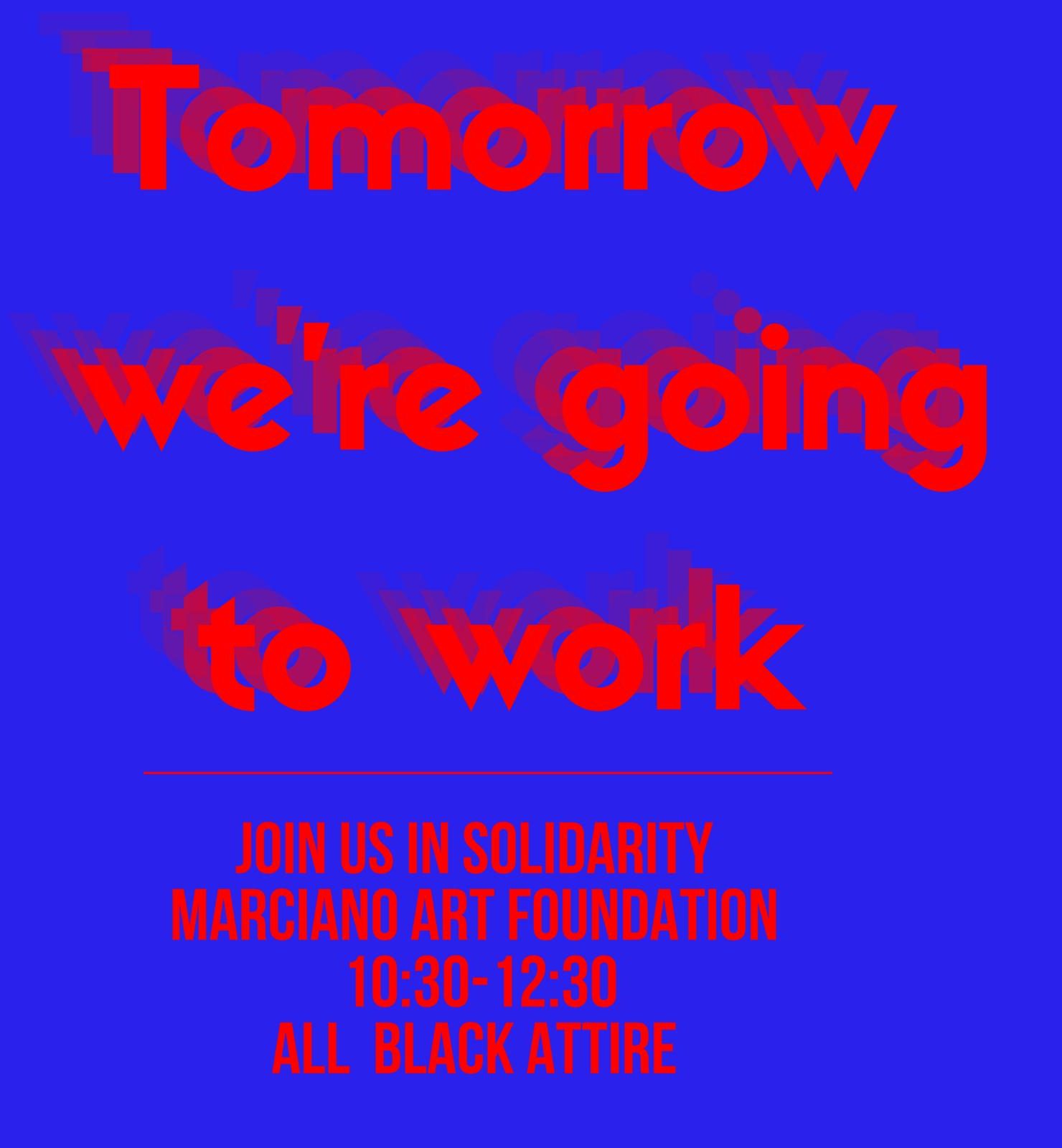

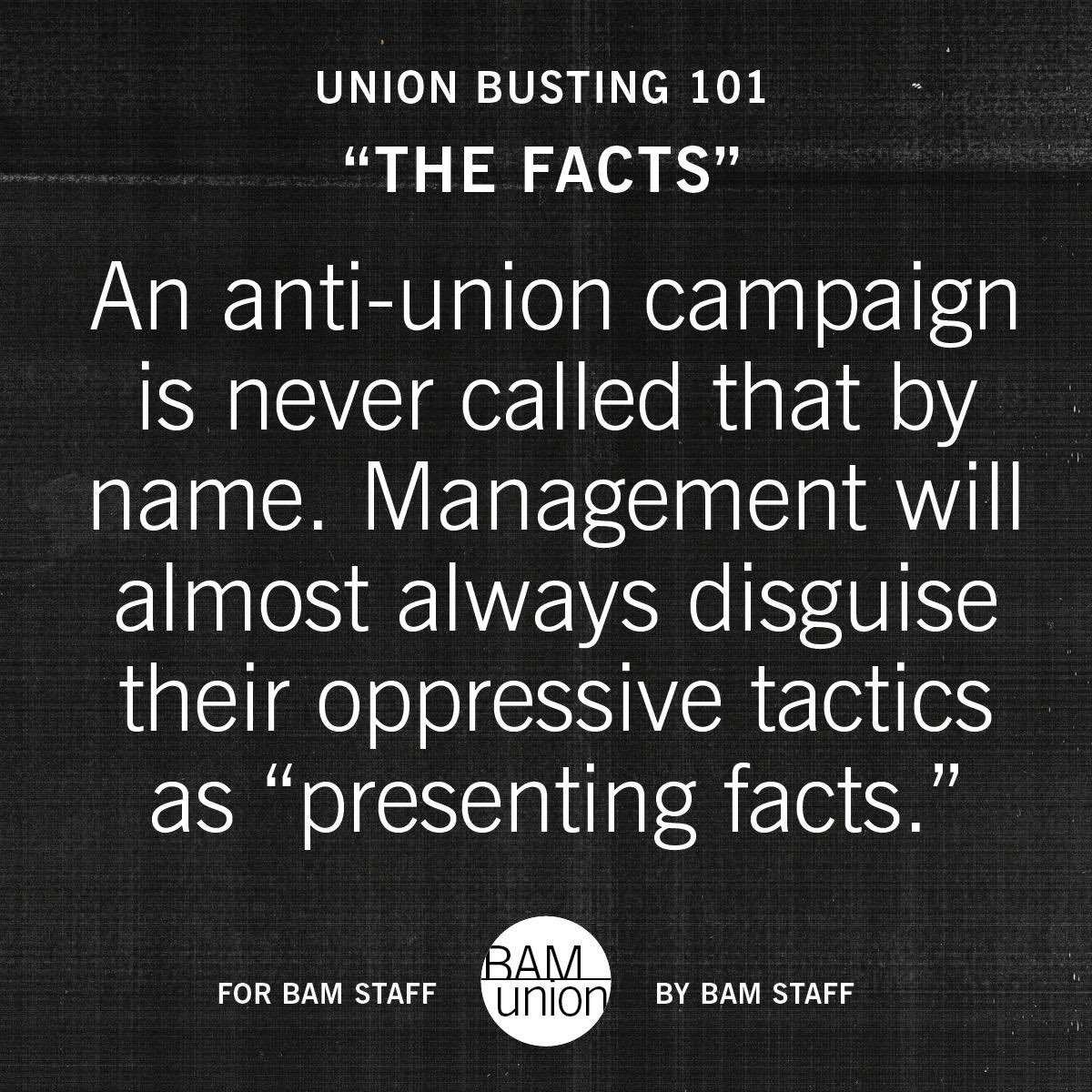

Many museums hired “union avoidance” law firms, conducted “captive audience” meetings, distributed anti-union literature, and otherwise slow-walked the unionization process. At the New Museum, management disputed the eligibility of associate curators in the bargaining unit. They even appealed the NLRB’s ruling on the matter and refused to allow union meetings on museum property. In a worst-case scenario, workers at the Marciano Art Foundation were laid off en masse four days after they declared their intention to unionize. The Marcianos, who in 1996 moved their Guess Jeans sweatshops from Southern California to Mexico and South America in the midst of a labor dispute, preferred to permanently close the foundation rather than work with a unionized staff.

Workers began to fight back. Understanding the vulnerability of a museum’s good name, they scheduled demonstrations to coincide with opening receptions and galas. The free admission policy at the Frye Art Museum enabled unionists to treat its galleries as essentially a public space. They invited supporters to a “Solidarity Night” the week of the union vote and later asked guests to fill out comment cards demanding that management bargain fairly.

Unions maintain active social media accounts, frequently reposting each other in solidarity. Hashtags such as #DoBetterGuggenheim and #BAMNotWorking have helped give voice to the frustrations of workers, as have press conferences and open letters to directors.

Throughout the industry, art workers affirmed that they were, in fact, workers. Their solidarity rejected exceptionalist rhetoric, which often undergirds coercion, and which frames every workplace as a “special environment” that relies on the “tireless dedication” of its staff. Such language is a close relative of the unabashed elitism that allowed the Guggenheim’s director to write, as workers deliberated whether to join the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE), “I do not want to work with a third party who has very limited experience in the museum field, whose membership is largely in the heating and air-conditioning and construction industries.” The next day, installers, maintenance workers, and art handlers voted overwhelmingly to unionize with IUOE.

Scene Break

In the final months of 2019, some signs of institutional softening to the inevitability of the wave appeared. At The Shed and at MOCA, unions quickly won voluntary recognition without need for an NLRB election. The New Museum Union won its first contract under threat of a strike, and other unions in the midst of protracted bargaining took note. This brief glimmer of worker power and management deference was soon snuffed out by the industry’s response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Forced to shut their doors, many institutions are now taking the opportunity to union-bust by firing and furloughing the majority of bargaining units. As museums choose not to dip into their endowments, workers are establishing mutual aid networks and pooling resources to pay for one another’s healthcare, food, utilities, and rent. Some unions were able to win formal protections for their members, including recall agreements and the extension of benefits, but in general there has been a brutal anti-labor backlash under the guise of pandemic response.

Even in this environment, the wave cannot be said to have crested or crashed. Some workers have found ways to organize in isolation. Staff at the Philadelphia Museum of Art announced a wall-to-wall union drive in May 2020. In June, on the day their museums re-opened to the public, workers from all four Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh announced their intention to unionize.

The response by art institutions to recent police killings of Black people, and to the uprising that followed, leaves much to be desired. Most museums, it seems, could summon only a single image of work by a Black artist from their collections, accompanied by a few half-hearted hashtags. At SFMOMA, management deleted a critical comment by a former worker who is Black. The director would eventually be compelled to apologize. In New York, the #OpenYourLobby campaign demanded that museums and theaters make their spaces accessible to demonstrators. Brooklyn Museum, MoMA PS1, and several independent cinemas complied, but others boarded up their street-level facades and became indistinguishable from the banks and high-end retailers nearby.

The suspension or cancellation of contracts with police officers at the Walker Art Center and the Minneapolis Institute of Art prompted circulation of another spreadsheet, this one collecting known institutional arrangements with police departments. Likewise, many unionists are pressuring the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) to withdraw its support of police unions.

Teachers’ unions are rejecting the presence of police in schools. Unionized bus drivers are refusing to serve as jail transport for arrested protestors. Factory workers are demanding to make ventilators instead of jet engines. What role might militant art workers play in the world to come?

Maxwell Paparella lives in New York City. His fiction and criticism have appeared in BOMB, The Brooklyn Rail, Screen Slate, and elsewhere.