The Moment Is Not Sufficient

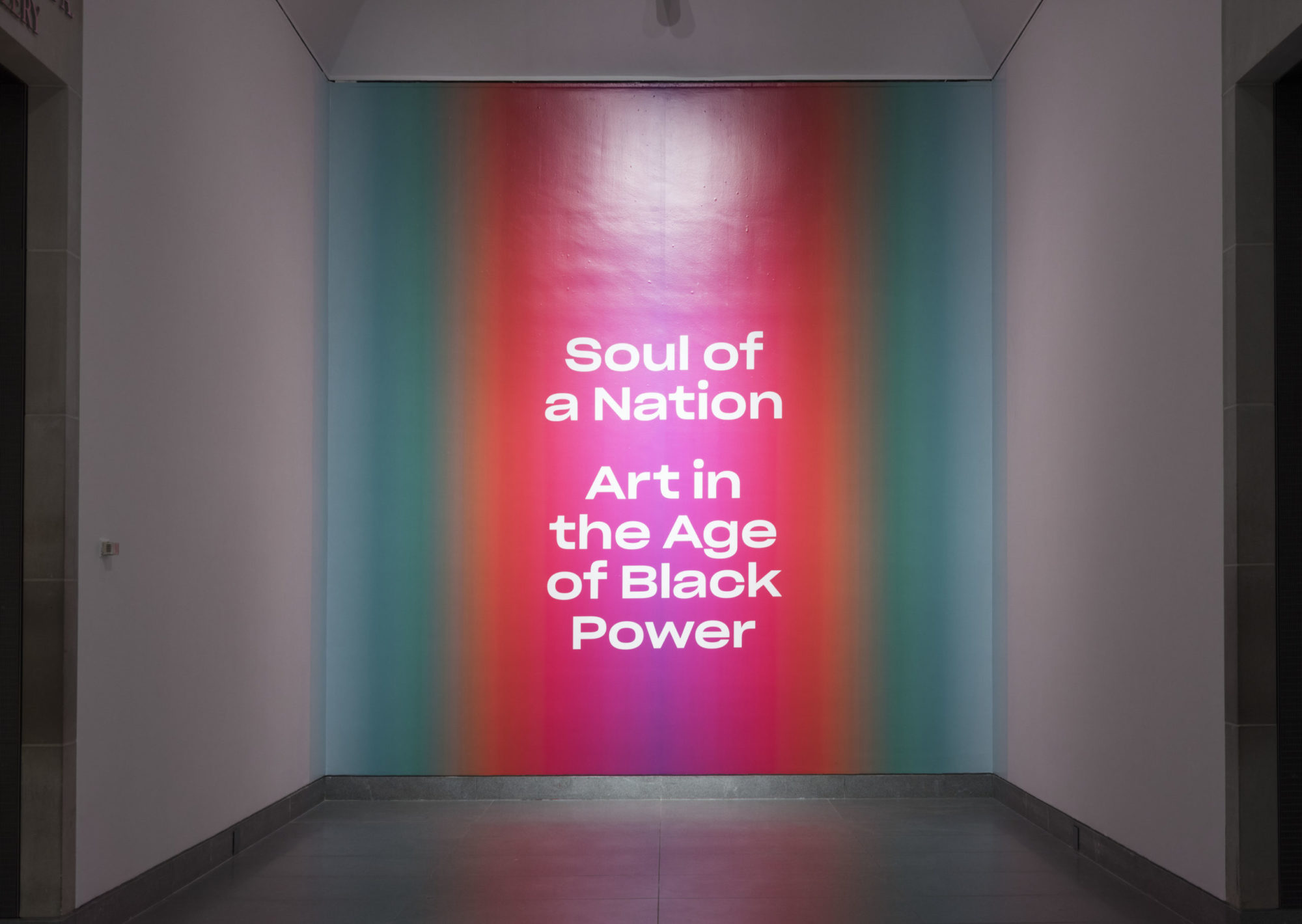

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, installation view, 2018-2019 [photo: Jonathan Dorado; courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY]

Share:

Art historian Bridget R. Cooks’ 2011 book, Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum, traces the history of major exhibitions of African American art. In it she writes, “Exhibitions of African American art in American art museums have been curated through two guiding methodologies: the anthropological approach, which displays the difference of racial Blackness from the elevated White ‘norm,’ and the corrective narrative, which aims to present the work of significant and overlooked African American artists to a mainstream audience.” The Chicago Art Institute presented the first museum showcase of Black artists in 1927 with The Negro in Art Week: Exhibition of Primitive African Sculpture, Modern Paintings, Sculpture, Drawings, Applied Art, and Books. Organized by philosopher and leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance Alain Locke, in collaboration with the Chicago Woman’s Club, The New Negro in Art Week (referencing Locke’s 1925 manifesto, The New Negro) brought together a mélange of unattributed African art objects with works by such major American artists as Henry Ossawa Tanner and Hale Woodruff. The exhibition offered a unique opportunity for Black artists to show their work in a mainstream museum, but not without a caveat. As Cooks states, “artists were required by the director of the Institute to ‘conform as near as possible to standards set by regular [read: Eurocentric] art museum exhibitions and exhibition galleries.’”

By 2020, these parameters have largely dissolved, but their remnants linger, seen perhaps most prominently in art criticism. The 2019 Whitney Biennial, for example, was criticized for its lack of radicality by a number of White reviewers. Their grievances drew barbed response from numerous Black artists and critics. Simone Leigh, whose work appeared in the Biennial, argued over Instagram that these critics lacked the knowledge to perceive the radical gestures in her work. In a similar vein, Xaviera Simmons wrote: “stop asking coloured bodies to hold the bulk of the rage over this country’s systemic maladies. And if we don’t deliver it for your visual pleasure (though I believe some works in the biennial actually do), do not sulk or lament that you miss the rage of the radical. That is also yours to own.”

30 Americans, installation view, 2019, [photo: Sean Murray; courtesy of The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia]

Leigh and Simmons’ responses reflect a larger issue in art history: most mainstream platforms for artistic discourse are still dominated by White men. The oft-mentioned art historical canon is still overwhelmingly White and overwhelmingly male, and the field of criticism is in the same boat. Asking why Black artists have largely been left out of the canon is perhaps too broad a question. The why seems obvious. Fear exists within the discipline of art history that changing the way it’s taught / displayed / understood (in other words, to de-center the importance of White artists) might somehow cause the whole field to crumble. This reluctance toward change doesn’t lead just to the exclusion of racialized artists from the conversation; it also extends to how artists whose work deals with issues of gender, sexuality, nationality, or disability are discussed, and the many intersections of such contexts. Cooks’ work proves useful for studying recent surveys of African American art and helps address the question of the segregated canon. We know why Black artists have been left out, but exhibitions often frame Black art in ways that insist upon a stereotypical notion of a radicalized other.

The idea of “Black art” has been so essentialized in art history that dissonance is often left out of the conversation surrounding artists of African descent. David Driskell observed that “Black art, unlike black music, was never valued purely for its power to captivate the spectator. Instead the art object always served as a sign of some other cognitive interest, and could be neither pleasurable nor exciting unless it was ‘socially significant.’” This expectation is inherently problematic, as it assumes that an artist’s work will not be understood or appreciated when separated from the context of the artist’s own racial identity. That assumption is, of course, the ultimate paradox when institutions present works by Black artists in a way that erases individual identity apart from race. However, two currently traveling survey exhibitions—Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power and 30 Americans—do not attempt to present a unifying or all-encompassing curatorial vision of Black art. Many of the included artworks deal with similar themes—identity, politics, history, beauty—but they do so with a much-needed multiplicity of artistic styles.

30 Americans, installation view, 2019, [photo: Sean Murray; courtesy of The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia]

Since opening at the Rubell Family Collection in Miami in December 2008, 30 Americans has traveled to almost 20 venues, including the Corcoran Gallery of Art in DC; the Detroit Institute of Arts; the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, MO; and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. Its presentation at the Honolulu Museum of Art opened in February 2020. It is slated to travel to the Albuquerque Museum in October, followed by the Columbia Museum of Art in South Carolina in September 2021. Representing a wide range of media—painting, drawing, assemblage, sculpture, and video—30 Americans introduces cross-generational dialogues with more than four decades of art. Robert Colescott, the oldest in the group, appears alongside Purvis Young and Soul of a Nation-era contemporaries David Hammons and Barkley Hendricks. Mark Bradford, Renée Green, Nick Cave, Glenn Ligon, and Lorna Simpson, among others, represent another group, all born around 1960, who came of age during the Black Arts Movement of the 60s and 70s. Nina Chanel Abney, Noah Davis, Rashid Johnson, Xaviera Simmons, and Kehinde Wiley belong to the youngest generation in the exhibition, and focus on the lineage of Black figuration and cultural memory set forth by their predecessors.

Much of the work challenges problematic or voyeuristic representations of Blackness, in a sense challenging the very existence of a show of Black art. Kara Walker’s room-sized tableau Camptown Ladies (1998) features the artist’s signature black silhouettes. The deceptively playful scene takes a moment to unpack, as its gruesome caricatures and their stereotyped physical attributes become more apparent through sustained looking. Walker’s work shares a language with Robert Colescott’s gestural figurative paintings, such as Modern Day Miracles (1988). His figures, like Walker’s, offer satirical commentary on stereotypes. In his words, “There were White people who were offended because they felt guilty [that] their people had created these images. [They] felt threatened by these paintings, which monumentalized these perceptions.”

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, installation view, 2018-2019 [photo: Jonathan Dorado; courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY]

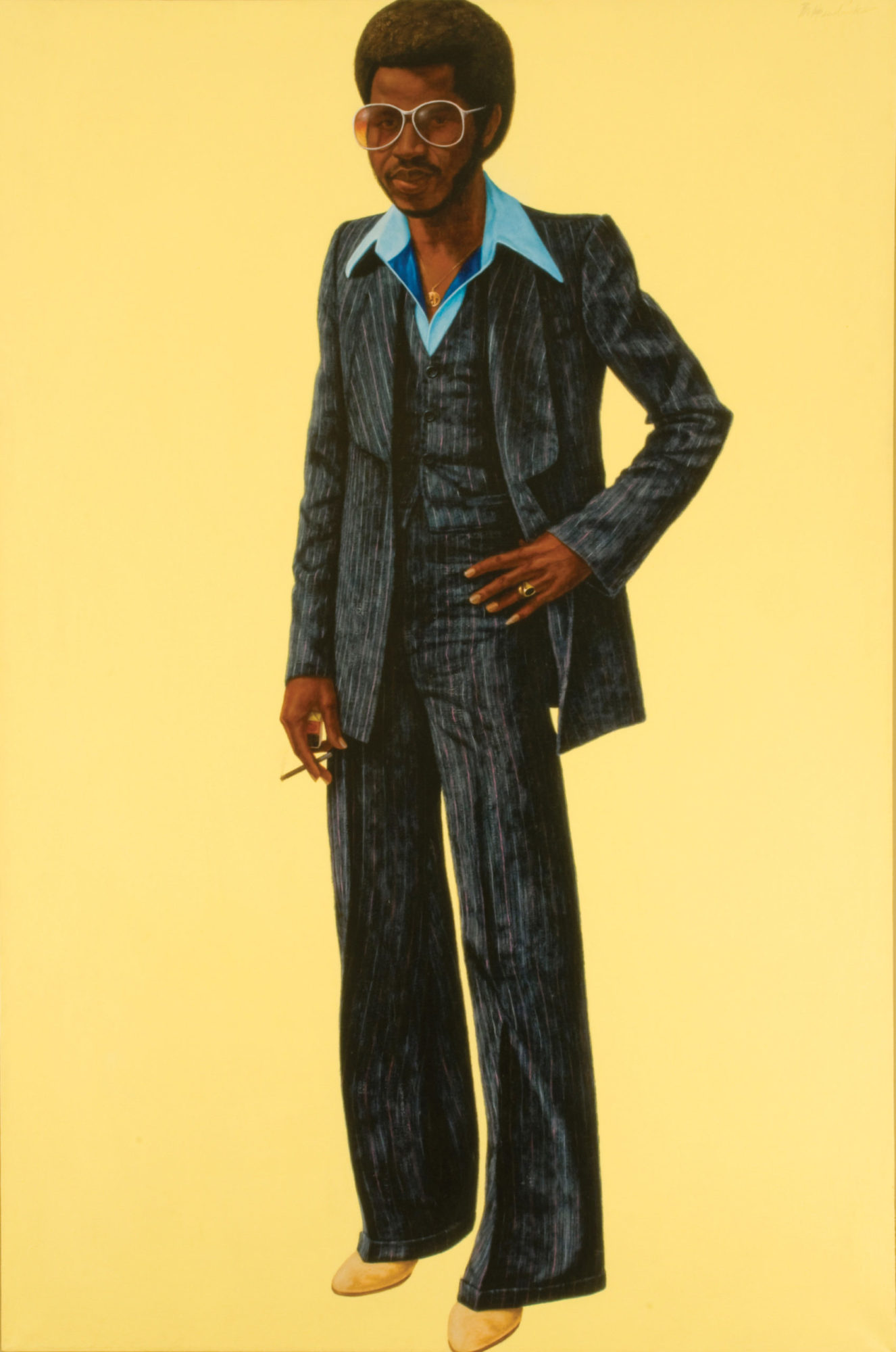

Two paintings by Barkley Hendricks, Noir (1978) and Fast Eddie Jive Niggah (1975), represent the late artist’s clean, almost minimalist approach to figure painting, with impeccably rendered, realistic Black figures on solid backgrounds. Noir depicts a man who could’ve easily been taken directly out of a Blaxploitation flick, with a well-groomed afro, orange-tinted aviators, yellow boots, and a pinstripe suit—complete with bell bottoms and wide, baby blue shirt collars. As with many of his other works, Hendricks embeds this painting with visual codes—the long pinky fingernail, the cigarette, the gold medallion and signet. The subject of a nude portrait, Fast Eddie, stands with his arms crossed, his weight shifted to his left side; he wears only a patterned bandana, and a silver medallion and bracelet. Both figures seem decidedly comfortable before the viewer, as if not totally unaware of our gaze, but simply unaffected by it.

Kehinde Wiley’s Sleep (2008) offers a different interpretation of the gaze. The monumental painting depicts a Black man lying in repose. Recalling one of Ingres’ odalisques or Titian’s Venuses, Wiley’s figure seems feminized in its passivity. A white cloth wraps around his waist and covers the flat surface beneath him. A soft light illuminates his body. Floral motifs—rendered in red, yellow, and green—occupy the background, while individual flowers seemingly float in front of the figure like an elegiac offering. The painting meditates on beauty and vulnerability, while connoting themes of power, voyeurism, and the violence inflicted upon Black bodies. Gary Simmons’ Duck, Duck, Noose (1992) and Klan Gate (1992) use visual symbols of oppression to reflect upon the terrible history of lynching, a brutal act made more devastating by the erasure of its victims.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, installation view, 2018-2019 [photo: Jonathan Dorado; courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY]

30 Americans also questions the imposition of an institutional voice onto the work of Black artists. The exhibition catalogue describes each work by using the artists’ own texts. The Nelson-Atkins went a step further in decentralizing the institution’s voice by consulting a panel of community members and including wall labels written by local artists, writers, and civic leaders next to each work. This strategy recognizes alternate, discursive possibilities, allowing cross-disciplinary responses to uncover new paradigms for Black art.

The show’s title recalls MoMA’s Americans series, a group of exhibitions that began in 1943 and were organized in response to criticism that the museum did not showcase the work of contemporary American artists. Although the Americans shows introduced artists who are now considered essential to the history of American art, they were largely lacking in diversity, with very few women artists and often no artists of color. 30 Americans, in its title alone, grapples with this legacy of marginalization in the art institution. In its various iterations, 30 Americans doesn’t always include exactly 30 artists. There are slight variations from venue to venue. The ultimate arbitrariness of the numbering plays an important role—it acknowledges the limits of its scope, but also subverts the definability of an “American” identity, prompting the question “who gets to be an American?”

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, installation view, 2018-2019 [photo: Jonathan Dorado; courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY]

Soul of a Nation opened at Tate Modern in 2017, where it featured a diverse range of painting, drawing, collage, assemblage, photography, sculpture, and video made by Black artists from 1963 to 1983. At an incredible scale, the show provides a vital perspective on a pivotal moment in US history: the years when the nation turned away from the Jim Crow era and toward the Civil Rights Movement. Three years and two continents after the 2017 opening at Tate Modern, the exhibition traveled to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in winter / spring 2018, followed by the Brooklyn Museum that fall, The Broad in Los Angeles in spring 2019, and then the de Young Museum in San Francisco, where it was on view until March 2020. The exhibition highlights crucial artist collectives such as the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, the Art Workers Coalition, and AfriCOBRA, all of which engaged in institutional critique to address the representation of Black artists in mainstream art spaces. A bold, minimalist suite of black–and–white paintings by artists of the Spiral Group greets viewers at the entrance to the show. Spiral—organized by Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Hale Woodruff, and Charles Alston—was founded in summer 1963, on the eve of the March on Washington. While traveling to the march that August, the artists discovered a mutual desire to define a uniquely Black aesthetic and address political tensions. Spiral was a short-lived but deeply impactful partnership among some unique artists, including landscape painter Richard Mayhew and figurative artist Emma Amos, the only woman of the group.

They mounted only one exhibition, First Group Showing: Works in Black and White, which ran May–June 1965. Several works from this show appear at the entry point to Soul of a Nation. Unified by color, the works vary in their stylistic and thematic approaches. America the Beautiful (1960), by Norman Lewis, combines the artist’s abstract expressionist style with representational iconography. The work features what at first appear to be randomized flecks of white paint on a deeply contrasted black field. Upon further examination, fragmented extremities, warped facial features, and weaponized religious symbols come to the foreground. Imagery of the Ku Klux Klan was so deeply embedded in American life, it seems fitting that in Lewis’ painting it hides in plain sight. U.S.A. ’65 (1965), by Merton Simpson, presents a similarly grotesque scene. His figures—with their ghostly features, glowing eyes, sharpened teeth, and contorted expressions—seem tormented. Inflammatory words and expressions such as “EXPOSED!”; “Who’s really behind”; and “the hidden crisis” appear on fragmented newsprint throughout the painting, a method of mixed-media collage that Simpson learned from his Spiral group colleague Romare Bearden. Informed by the assassination of Malcolm X in February 1965 and the Selma to Montgomery March led by Martin Luther King Jr. that March, U.S.A. ’65 conveys an overwhelming sense of tension, urgency, and civil unrest, but also duality; he portrays both the unchecked aggression of the oppressor and the anguish of the oppressed.

Farther uptown, in Harlem, another artist collective, the Kamoinge Workshop—from a word meaning “a group of people working together” in the Kenyan language Kikuyu—assembled with the intention of increasing agency among Black photographers. Less politically inclined, the group focused more on cultivating and supporting its artists, thus providing a unique forum in which they could exhibit their work and develop their practices as fine-art photographers. Roy DeCarava, known for the moodiness of his contemplative black–and–white portraiture, led the first iteration of the group upon its founding in 1963. DeCarava traveled to the nation’s capital for the March on Washington, where he shot Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, DC. Weeks later, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL, was bombed by the Ku Klux Klan, killing four young girls. Five men, 1964 depicts members of the memorial service as they depart, their faces practically shrouded in shadows but still recognizably forlorn. These figures, too, are anonymous, but here it signifies how their grief is shared by a multitude.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Noir, 1978, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 48 inches, [courtesy of The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, and of Rubell Family Collection, Miami]

Artists in Los Angeles responded to the psychological and physical devastation caused by over–policing and riots in the 1960s. Among others, Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, and Melvin Edwards turned to assemblage and found-object art made from street detritus to reflect upon this violent moment, essentially collecting history as it unfolded. In Chicago, the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC, pronounced oh-bah-see) came together in 1967, on the South Side of Chicago, to support the Black liberation struggle. A year later, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., some OBAC member created AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists). AfriCOBRA founding member Jae Jarrell’s garments—including Revolutionary Suit (1969)—embody the group’s brightly colored, African-inspired aesthetic. Her husband, artist Wadsworth Jarrell, used a highly circulated image of activist Angela Davis from a 1970 issue of Life magazine, pointedly titled The Making of a Fugitive, for his kaleidoscopic portrait Revolutionary (1971). Painted at a moment when artist groups were protesting problematic displays of Black art at White-run institutions, Revolutionary shows a desire not only to create a uniquely Black style of art, but to counteract pre-existing notions of Black personhood as seen through the lens of White culture.

The debate over how to define Black art and the Black aesthetic played out among many of the artists seen in Soul of a Nation, especially in the conflict between abstraction and figuration. In the Brooklyn Museum’s presentation of Soul of a Nation, one of Sam Gilliam’s monumental draped canvases, Carousel Change (1970), introduced a gallery dedicated to abstraction. Artists such as William T. Williams, Howardena Pindell, Jack Whitten, and Alma Thomas explored the limits of geometric forms, while others including Gilliam, Joe Overstreet, and Frank Bowling—the only non-US–born artist on view—incorporated more expressionistic brushwork. Often larger than life, and rendered in a dizzying array of color, these paintings seem to pull the viewer into a kaleidoscopic space.

Figurative artists, by contrast, used their practices to reclaim authorship of narrative identities in their representation of Black subjects. Figurative painter and draftsman Charles White, who in 2019 was the subject of a long overdue retrospective at MoMA, observed: “Art must be an integral part of the struggle …. It can’t simply mirror what’s taking place …. It must ally itself with the forces of liberation.” The works of Faith Ringgold, Benny Andrews, David Hammons, and Barbara Jones-Hogu, to name a few, adopt the visual language of protest to deliver unflinching responses to social injustice and violence. Other artists, including Emma Amos, Beauford Delaney, and Barkley Hendricks, worked in a less explicitly political mode. Pieces such as Delaney’s Portrait of James Baldwin (1971), Amos’ Eva the Babysitter (1973), and Hendricks’ Blood (Donald Formey) (1975) depict dignified figures, collected and commanding in their presence alone. The figures aren’t radical, nor do they need to be; depicting Black figures with this kind of dignity could in itself be seen as a political act.

Mickalene Thomas, Baby I Am Ready Now, 2007, Diptych, acrylic rhinestone and enamel on wooden panel, 72 x 132 inches overall, 72 x 60 inches left panel, 72 x 72 inches right panel, [courtesy of The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, and of Rubell Family Collection, Miami]

After The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its controversial Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968 exhibition in 1969 without featuring a single Black artist, the museum held a symposium, The Black Artist in America, during which Romare Bearden, Hale Woodruff, Jacob Lawrence, Sam Gilliam, Richard Hunt, Tom Lloyd, and William T. Williams disputed the phrase “Black art.” Lloyd argued that his race defined his identity as an artist. Lawrence responded, “I think you are an artist who happens to be Black, but you’re not a Black artist.” This argument remains relevant today. As Black artists address issues of identity in their work at the risk of pigeonholing themselves on the basis of race, and as they address the social and political structures in our country that treat Black Americans as a collective, Soul of a Nation presents a key moment in this ongoing debate—a turning point, rather than a definitive beginning or end. The show presents a multiplicity of voices that may all have the same goal, but don’t all agree on the best way to reach it, which is an honest reflection of the struggle.

Soul of a Nation and 30 Americans demonstrate that “Black art” is a varied concept. The way we define the phrase is tied to the way we think about American identity and who has the ability to claim it. The homogenization of Black artists reflects the social and political structures in our country that treat Black Americans as a collective. The scope of the exhibition and each artist’s diverse approach to art-making complicate our understanding of Black art. The trajectory of these shows reflects a seemingly boundless potential, one that resists the monolithic approach to identity-based exhibitions. But the problem of the Black art exhibition is not that it separates Black artists from the rest of the art historical canon, but that institutions still need these exhibitions to serve as a kind of institutional virtue–signaling that demonstrates their ostensible support of diversity, while still allowing them to segregate artists of color as definitive others. This outcome has a reflection made evident by a dangerous tendency in art criticism to frame discussions of artists of color with relation to trends. When an artist is described as having a moment, it implies that their significance is temporary. Such artificial bookending exposes the limiting mindset of critics, curators, and scholars who have long ignored artists of color. As Soul of a Nation and 30 Americans continue to travel to new venues over the course of years, they resist this sort of momentary framing. The moment is no longer sufficient; rather than a moment, Black art deserves a permanent place in the discourse.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Spring 2020 // Art of the New Civil Rights Era.

Re’al Christian is a writer and art historian based in New York City. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, Art in Print, BOMB, and The Brooklyn Rail. She is an MA candidate in art history at Hunter College, and a curatorial fellow at the Hunter College Art Galleries. She earned her bachelor’s degree in Art History and Media Studies at New York University.