The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

The French Dispatch: How Wes Anderson Critics Gaslit Themselves, and Me

Share:

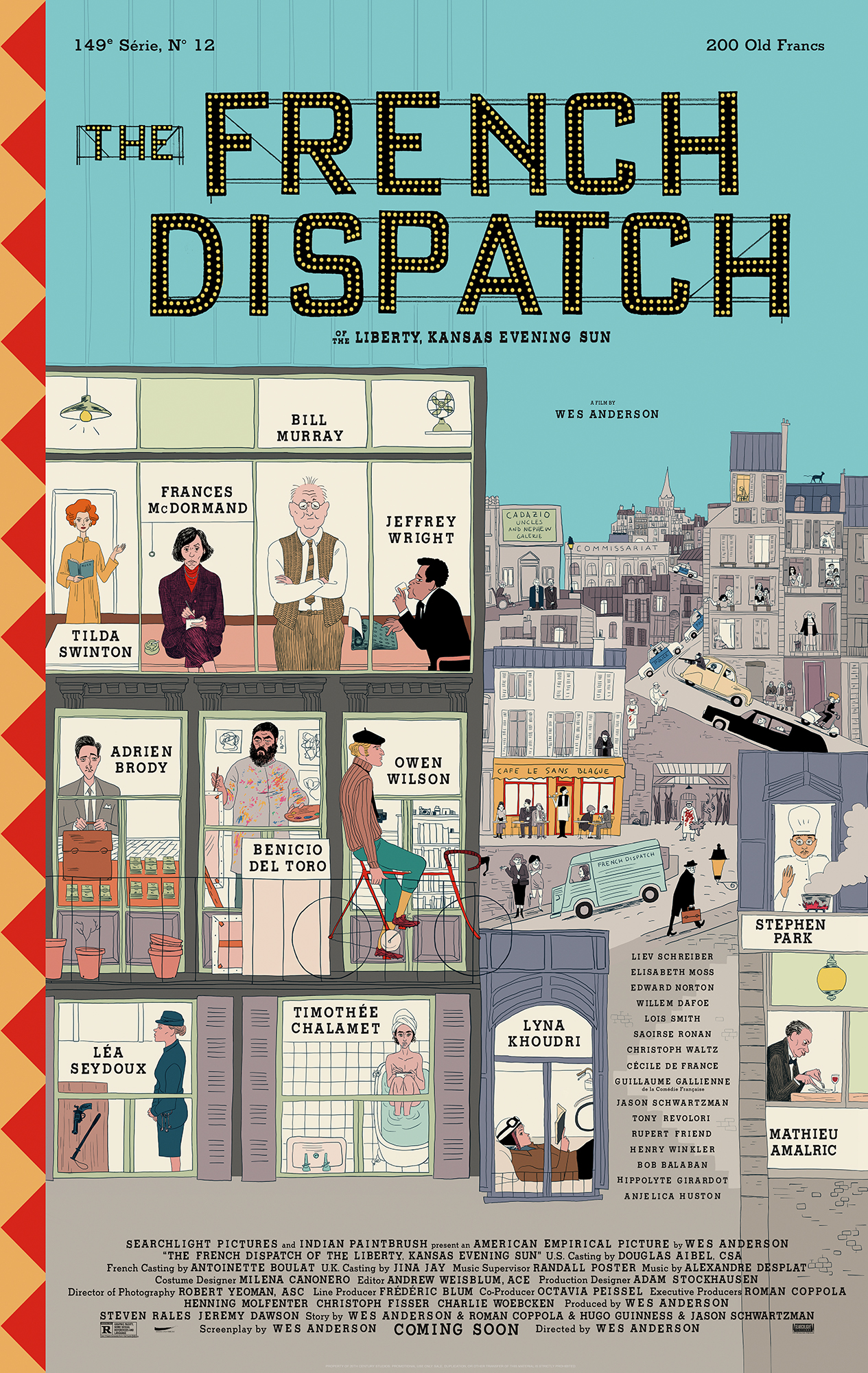

The French Dispatch Poster, 2021

There is a wide chasm between what The French Dispatch presents itself to be and what it is. The movie’s flaws go beyond surface level; the rot is in the bones, and the only option is to amputate. Wes Anderson’s worst tendencies are on display. The charms and subliminal emotional depths of his previous films are absent. He renders characters here as absurd caricatures, and the underbaked, overstuffed narratives ooze with bad politics and pseudo-moralities, leaving a god-awful taste.

These faults aren’t subtle. Perhaps even more disconcerting than the film itself is its critical reaction, specifically, and notably, from major media outlets and White critics. Why is Anderson impervious to criticism when other filmmakers would be instantly called out? What, one may ask, the fuck?

Before answering that question, we must look at the story of The French Dispatch. I feel tired just thinking about it. Stay with me.

The editor of The French Dispatch (Bill Murray) has died, and with him the publication itself—a ship going down with its captain, so to speak. The movie presents itself as the deconstructed filmic version of the final issue of the titular magazine, nesting narratives within narratives within narratives. First, the magazine as a clackity but functioning machine of quirky writers, editors, accompanying staff, etc. Then, a layer that focuses on a few individual writers themselves; within their own personal stories, dramatizations of their contributions to the final issue of The Dispatch unfold.

A.O. Scott of The New York Times explains, “It’s not really possible to spoil any of the major episodes, but it’s also foolish to try to summarize them.” Foolish, perhaps, but it didn’t stop many from trying, including Sophie Monks Kaufman of Hyperallergic, to whom I owe the following outsourcing:

The film is … divided into an obituary, three stories, and an endnote. Berensen leads the first story, concerning the fortunes of convicted murderer Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro in wild-man mode), whose abstract nude painting of his prison guard muse Simone (Léa Seydoux) draws the attention of the art world. Next comes a political report from Krementz, who embeds with, and then beds, chess player and student revolution leader Zeffirelli B (Timothée Chalamet). Finally, Wright [Jeffrey Wright] goes to interview a famous police chef, only to be drawn into a caper after the young son of the commissaire (Matthieu [sic] Amalric) is kidnapped.

The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

So there.

I read the reviews before watching The French Dispatch. The film is explicitly modelled upon a fictionalized version of The New Yorker, and The New Yorker’s critic Richard Brody explicitly loved it. “Perhaps Anderson’s best film to date,” wrote Brody. Like many others, Brody waffled to explain the structure and narrative of the film:

The effort even to make sense of what’s going on—to parse the action into its constituent elements, to assemble its narratives, its moods, and its ideas—leads to inevitable oversimplifications, the reduction of roiling cinematic energy into mere mental snapshots. In my mind, it’s necessary to see “The French Dispatch” twice in order to see it fully even once, which I mean as a high artistic compliment.

Brody was not alone in his praise. Many reviewers, not only ones ladened with a healthy serving of bias, paid a great many such compliments. I did end up seeing The French Dispatch twice. After the first viewing, I felt, perhaps, a tad reductive toward the roilingness, as Brody warned. After a second viewing, I felt cheated. Not by Wes Anderson—I never trusted that stylish bon vivant—but by my colleagues from afar. Did we watch the same movie? Were these raving reviewers gaslighting me like a dirty 1850s Parisian boulevard? Was my concealed canned movie theater wine (Underwood Pinot Noir, 375ml) laced with leftover New Year’s hallucinogens?

A consistent focus of criticism toward Anderson’s work concerns his famously unique aesthetic. His hyper-attention to the minute details of every shot, precise emphasis on visual symmetry and balance, cheeky use of color, and the constant barrage of nostalgic signifiers rub some folks the wrong way.

His oeuvre is twee at its most aggressive and dedicated. It’s twee before twee was twee, and, it has been oft noted, very, very White. “He’s a taste you either enjoy or don’t, like cilantro or Campari,” writes A.O. Scott, as if it’s not worth arguing about. Sometimes, reviewers of Anderson’s films point to the razzle dazzle twazzle of it all as a soft criticism, as being a bit much, before quickly excusing it in praise of his artistic commitment. The French Dispatch showcases this aesthetic at full thrust, which is then bolstered by the film’s hectic structure. Dizzying, sure, even delightful (if it’s to your taste), but ultimately a smokescreen. The wreckage comes from the narratives. Perhaps some things stood out in Monks Kaufman’s description.

The story from the magazine’s art section features a relationship between incarcerated artist Moses Rosenthaler (played by Puerto Rican actor Benicio Del Toro) and prison guard Simone. Rosenthaler loves Simone and considers her his muse. Simone spends most of her time posing nude, and verbally and physically abusing Rosenthaler. K. Austin Collins of Rolling Stone describes this relationship as “kinky.” The New Yorker’s Brody describes it as “intensely erotic,” as if it’s all just innocent role play and not a depiction of a gross abuse of power.

The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

The problematic nature of this relationship is heightened by Anderson’s choice to present Rosenthaler as a kind of animal-man. He growls and bares his teeth, and the phrase “caged animal” is uttered in reverent tones more than once. This vignette’s author, art critic Berenson (Tilda Swinton), presents the story via a lecture about Rosenthaler to a fancy audience. She muses on Simone’s attraction to Rosenthaler: “Something about the captivation of others enhances the feeling of their own freedom.” A White prison guard having sex with an inmate, and then being romanticized through an art historical lens, is cringe at best and violent at worst. The most generous way to interpret this plotline is as a searing indictment of art criticism, and the art world at large. But Anderson doesn’t appear interested in morality. Neither was the audience in the theater. Rosenthaler growled; they laughed.

All three of the main stories in The French Dispatch are pro-cop. It isn’t low-key. It’s no secret that Anderson enjoys using a character’s profession as an aesthetic device, but it’s not just that a lot of cops appear in the movie. They are invariably the good guys—level-headed, clever, voices of reason, and in Simone’s case, alluring. Even Timothée Chalamet’s charisma as the student movement leader can’t distract from the absolutely insane statement made by Dispatch writer Krementz, during the student protester episode: “You’re all in this together, even the riot police.” This statement, which is never contradicted, and is presented as a moment of reason during a whimsical chess match between students and officers, is immediately followed by riot police violently charging the teenagers, which is depicted as … justified? Slap-sticky? The student protesters come off as naïve and pouty, grumpy about nothing, and running on cigarettes and hormones. I wouldn’t be surprised if Anderson never attended a protest in the summer of 2020, but because he seems to enjoy print media so much, I thought he might have read an article.

The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

The final story, from the “Taste and Smells” section, is a convoluted tale of a famous cook for a police station, written and told by Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright). Roebuck is audaciously styled as a James Baldwinesque character. In this narrative, the chief of police’s son is kidnapped, and the famous chef (Stephen Park) ends up saving the day at the risk of his own life. There’s also a ludicrous dinner scene that turns the police chief’s office into an episode of Chef’s Table, an animated car chase that almost works, and an unexplainable and very brief Saoirse Ronan appearance. An exchange occurs between critic and chef at the very end of this chapter, in which they discuss the moral labor of being an immigrant.

The dialogue feels disingenuous for a movie that spends almost the entirety of its hour and 48 minutes actively affirming—and twee-ifying—institutional violence. Or, at minimum, treating attempts to dismantle such institutions as, at best, petty and, by default, nonexistent.

From Brody, one last time, who seems, to a degree, aware of the film’s recurrent emphasis on oppressive systems:

[Anderson’s] views of society’s turbulence, individuals’ violence, and institutions’ cruelty are inseparable from the sense of style that heroic resisters bring to it—and that group includes both the people who confront crushing power and those who report on it.

But who is confronting this crushing power? Certainly not the characters.

Anderson’s characters typically overcome their cartoonish hyper-stylization with some level of emotional distancing, which, when done well—as in The Royal Tenenbaums—subsides to let their inner turmoil surface just enough to evoke strong feelings of empathy for their pain, their humanity. None of that happens in The French Dispatch. Its band of misfits is not endearing. They’ve been stripped of nuance and purpose, leaving only empty caricatures.

The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

The French Dispatch, 2021, still, screenshot

Something in Anderson’s formula has gone rancid, and in its place has grown shitty narratives with fucked-up politics. Intentionally or not, he has aligned his well-documented aesthetic of Whiteness with disdainful cynicism to create a world in which cops are reasonable, protesters are dumb, and violent abuses of power are not only erotic but inspirational.

And yet, these troubling problems are largely absent from the reviews. Did the reviewers really watch the movie, or did they just proffer the review they had already imagined writing? How is it permissible for Anderson to receive so many passes from critics in a year following unprecedented cultural shifts and civil unrest around the Janus of police brutality and white supremacy? For these reviewers to find invisible such glaring issues speaks strongly to the privilege that Anderson enacts. The core deficiency is simple: A White director so caught up in aesthetic that he fails to consider what he’s doing, and critics who have decided not to care.

EC Flamming is a writer in Atlanta. Her work focuses on the cultural impacts of moving images and contemporary art to explore how media consumption shapes and reflects social relations. The last movie she watched was Dangerous Liaisons, and the last television show was Alone. She recommends both. If you have a movie or television suggestion, DM@ecflamming