The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse

The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse. Installation View. May 22, 2021 – September 6, 2021

Share:

Growing up in Decatur, IL, meant that the hip-hop which influenced me was a combination of art and artists from the East and the West (coasts). But many folks from Illinois identified with the South. This alignment makes sense. My grandparents came to the Midwest from Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas. My family wasn’t much different from many of the others who visited those places regularly or whose family members from down south came up to visit them on occasion. My relationship to hip-hop, then, is informed by this “North-South cultural dialogue,” which is what, in the “ethnomemoir” portions of his book Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop, Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. calls the singular, yet typical stories of his own Southern ancestors, other historical actors, and their effect on his experiences of growing up in Chicago. It’s difficult for me to interpret my experience through any other lens.

The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse, installation view, 2021 [photo: Travis Fullerton; courtesy of Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond]

This vantage point was made clear when I visited The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. The show is divided into three parts: landscape, religion, and the Black body, and so references to place, ways of thought, and corporeality abound. It consists of works by 93 artists, among them Thornton Dial, Allison Janae Hamilton, Jason Moran, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Kara Walker, and William Edmondson. The exhibition also includes found art and other contemporary material cultural artifacts such as “grillz,” live-show DAT machines, and such stage-worn artifacts as the flower suit CeeLo Green wore for his November 11, 2015 performance of “Music to My Soul” on The X Factor (UK).

The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse, installation view, 2021 [photo: Travis Fullerton; courtesy of Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond]

The text at the exhibition’s entrance cites the “clarion call by André 3000, of the Atlanta-based duo OutKast, who proclaimed that the South had something to say.” It goes on to note that, “The assertion shone a light into a rich, centuries-old repository of aesthetic traditions rooted in the fraught history of this nation.” André’s speech at the 1995 Source Awards is an undoubtedly important, and incredibly prescient, declaration of the South’s hip-hop presence and future influence. To my mind it echoed the pronouncement made two years earlier in the title of Memphis, Tennessee duo 8Ball & MJG’s debut album, Comin’ Out Hard.

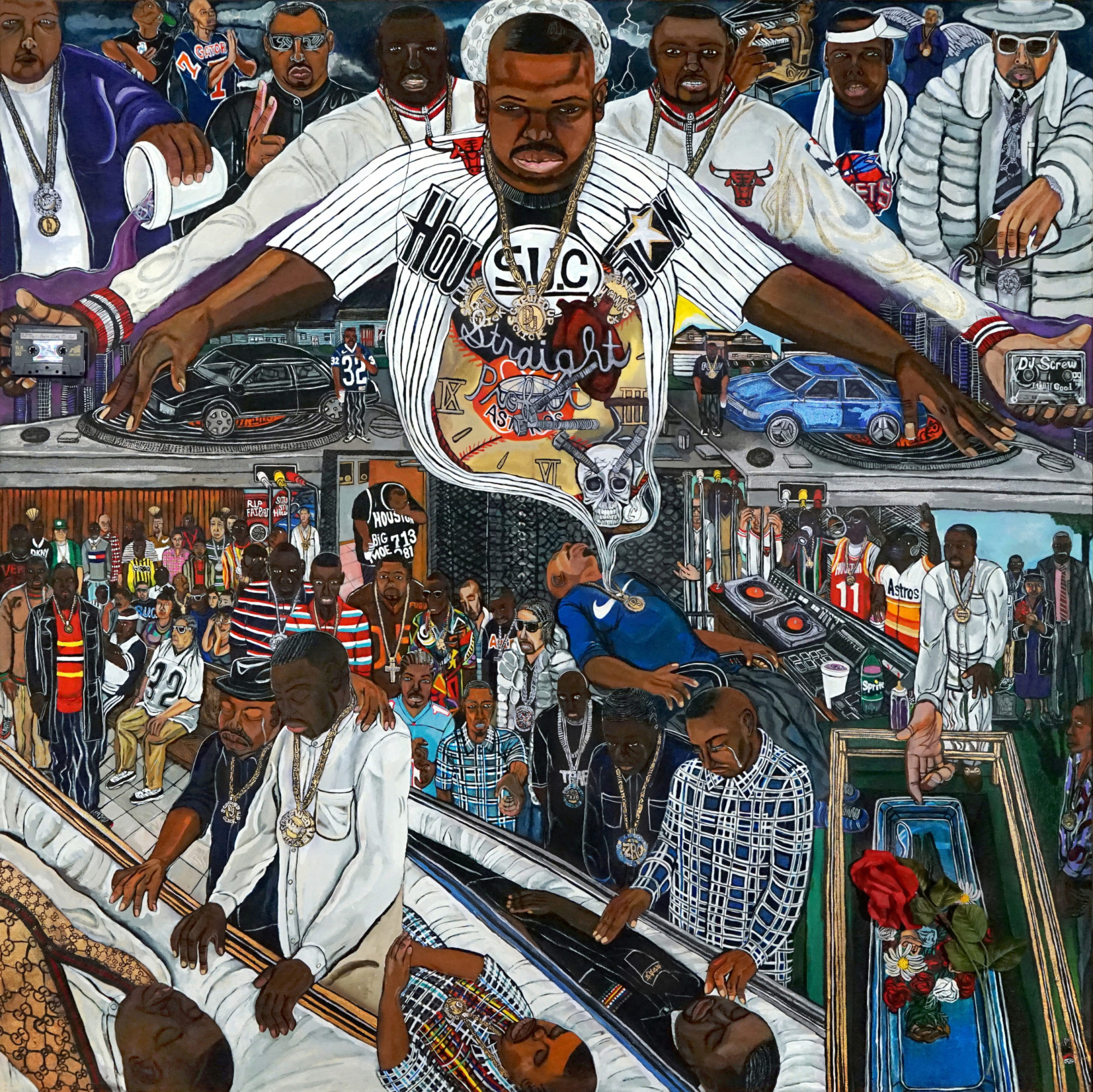

El Franco Lee II, DJ Screw in Heaven 2, 2016, acrylic on black canvas with cassette tape [courtesy of the artist and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts]

Slab, in the lobby of the museum, says what 3000 says and does what ’Ball and ’G do. It’s a pearl-white, gold-trimmed, “beautified” 1990 Cadillac Brougham. Curator Valerie Cassel Oliver notes that SLAB is an acronym for “slow loud and bangin’.” The VMFA commissioned the stylized car by former No Limit rapper Richard “Fiend” Jones for the exhibition. The car’s inclusion isn’t a metaphor; it’s the beginning of a journey that continues as you descend the stairs into the exhibition. Even as Slab conjures mental images of “swangin’ and bangin’,” Paul Stephen Benjamin’s installation Summer Breeze features a stack of television sets. Some play video snippets of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” Holiday’s sung phrase, “black bodies swingin’,” mixes with a rendition by Jill Scott on other screens. Behind them, most of the televisions show a young Black girl swinging on a playground swing.

Nadine Robinson, Coronation Theme: Organon, 2008, Speakers, soundsystem and mixed media [courtesy of the artist and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond]

Another exhibition highlight was Nadine Robinson’s sound collage installation Coronation Theme: Organon. It features a wall of speakers playing the distorted sounds of Birmingham protesters, police dogs, and firehoses with one of George Frideric Handel’s coronation anthems. Arthur Jafa’s affecting video Love is the Message, The Message is Death closes the exhibition. Set to “Ultralight Beam” by Kanye West, Chance the Rapper, and Kirk Franklin, and employing found footage, it interlaces moments of Black joy and pain, trial and triumph, life and death. I sat through the seven-minute video twice.

Oliver describes a “complex framing” for the dialogue into which the artists in the show have been placed. It raises earnest questions for me about which music is—or is not—included under the Dirty South umbrella. I’m an artist who is heavily influenced by the art I grew up hearing. My work is unquestionably informed by a North-South cultural dialogue, even more so because I have been studying, working, and living in the South since 2013. I was not at all surprised to see artifacts from Richmond native son Mad Skillz. I also know that Richmond is the second capital of the Confederacy, which seems sufficiently Southern. Living in Virginia now leaves no doubt for me that it is a Southern state. I hear and see the influence of the South in the music that comes from here. But I don’t know if Mad Skillz or the likewise incredibly influential and talented cohort of musicians from Virginia—Missy Elliott, Timbaland, The Lady of Rage, and Pharrell Williams, to name a few—register primarily as “Dirty South” to me (though they are all inarguably Southern artists). It makes me wonder what combination of sound and sites constitute the vision of the Dirty South presented, and whether it’s more geospecific than sonic. I’m not sure if Nelly and the St. Lunatics claim the Dirty South, but the album Country Grammar and the country grammar he and his group employ are certainly influenced by what I associate with the Dirty South, at least sonically.

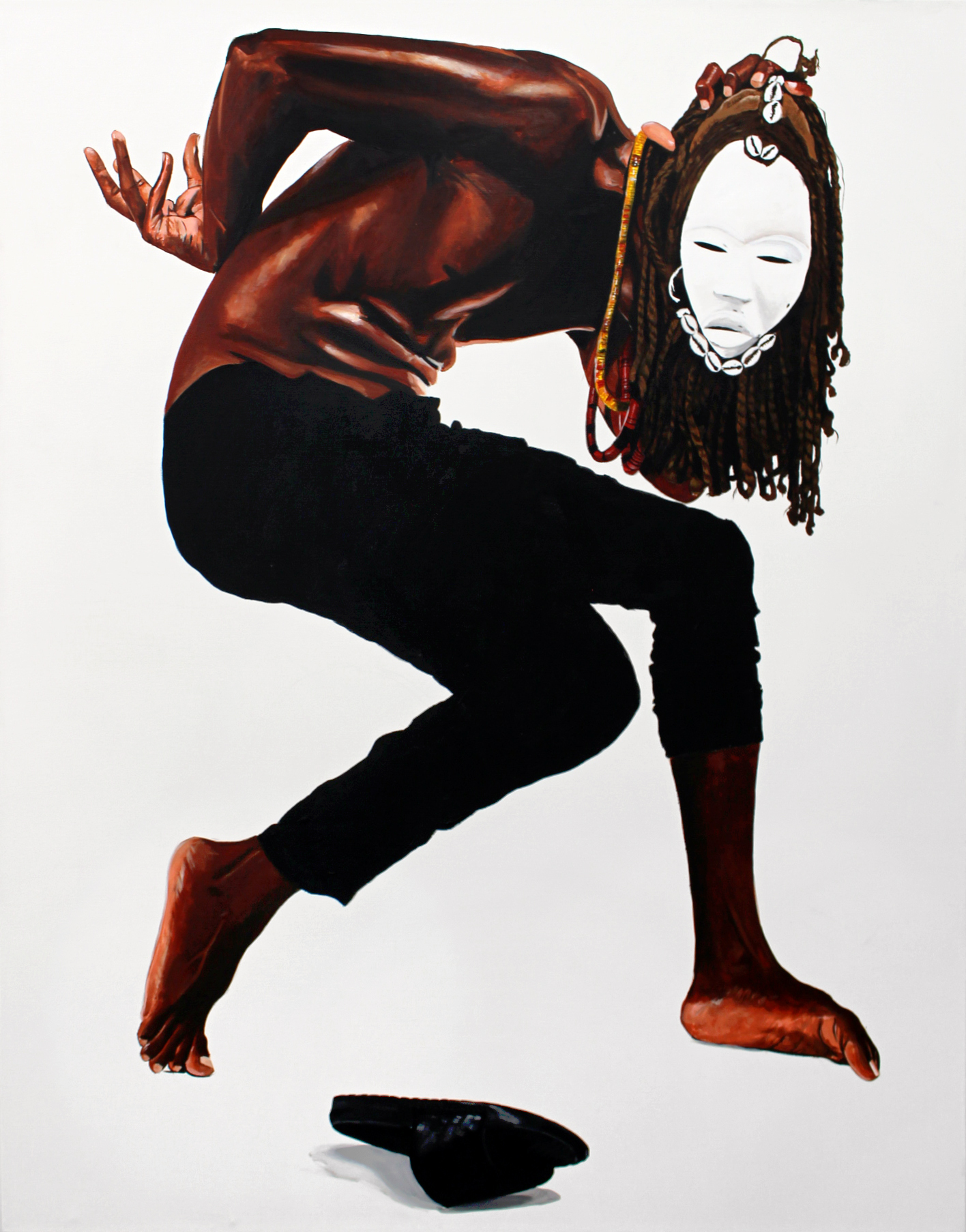

Fahamu Pecou, Dobale to the Spirit, 2017, acrylic on canvas [courtesy Fahamu Pecou, Studio KAWO/Fahamu Pecou Art, and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond]

Although I would have loved to see 8Ball & MJG featured more prominently (they are conspicuously absent from the Memphis music graphic that lists influential Dirty South places and artists), The Dirty South is dope. It reminds me how back-home and down-home feel. It’s like a Southern Black front porch or back yard where we discuss who we are, what we carry, what brought us here, where we intend to go, and how we will get there. No doubt, there is music playing, and there’s a slab that can be heard rumbling as it turns the corner slowly, its driver trying to decide whether to park it out front on the street where it can be seen or in the yard where it can be felt—or to do another circle around the block for a bit of both.

***

“The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse” will travel to be on view at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston from October 23, 2021 — February 6, 2022.

A.D. Carson is currently an assistant professor of Hip-Hop & the Global South at the University of Virginia. Follow Carson on Twitter/IG @aydeethegreat.