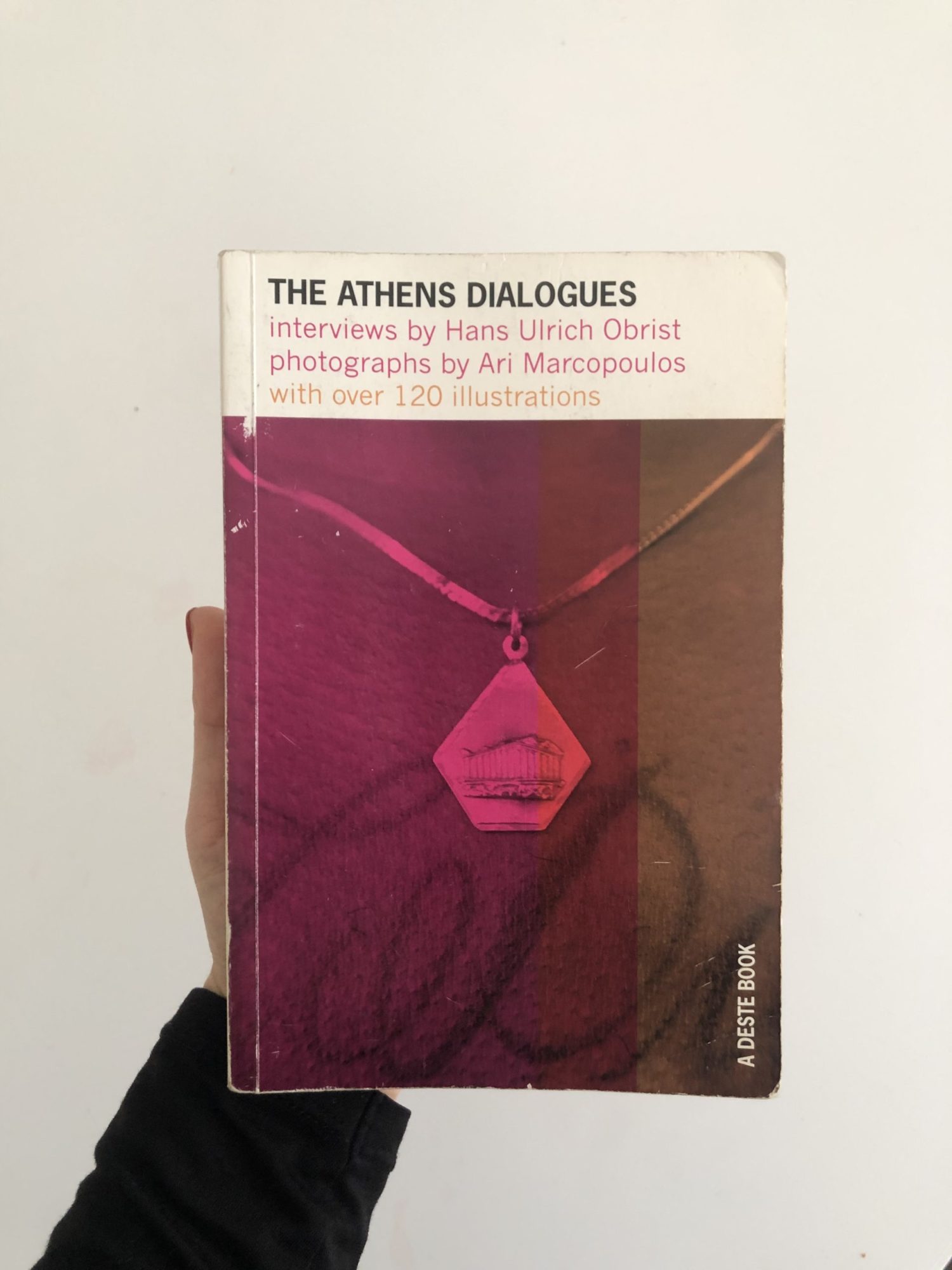

The Athens Dialogues: Interviews by Hans Ulrich Obrist

Share:

“The future is built from fragments of the past” Hans Ulrich Obrist muses, invoking Erwin Panofsky in the introduction to The Athens Dialogues. This fragmentary future is constructed, Obrist asserts, in ways that depend upon conversations. This outlook is, in many ways, the main thrust of his curatorial practice. Obrist’s Interview Project, ongoing for decades, is a curatorial framework wherein he conducts extended interviews with artists, many of which last for hours. With this method he approaches the central question of The Athens Dialogues: “how the influence of Greek antiquity is absorbed and contested by contemporary practitioners.” Consisting of interviews with 12 artists and 1 architect, alongside a photo essay by Ari Marcopoulos, the book posits Obrist’s interpretation of Panofsky to address this question.

The curator’s introduction lays some wobbly ground, the basis of which leans into a Western art-historical narrative of linear progress. The application of Panofsky’s quote to the relationship between Greek antiquity (past) and contemporary art (future) creates a faulty framework in which contemporary art is post-time and post-place. This perception of “past” is a common positioning for places with well-known ancient histories in the Western imagination, and Greek antiquity is often framed as a source, rather than an actual context, with its own specificity and entanglements. Obrist’s dependence upon this perspective is solidified by his later question, “is antiquity a toolbox?” The question creates a visual—one uncomfortably analogous to the looting of Athens—in which ruins can be re-narrativized with ease, and without conceptual or cultural implications.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, The Athens Dialogues: Interviews by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Koenig Books, 2018. [photo: Magdalyn Asimakis]

The question of Greek antiquity and contemporary art, in itself, has the potential to address issues of visuality; transnational dialogues, including race, gender, and sexuality; appropriation; cultural diplomacy; and the narrativization of art history, among other prescient issues that many of the interviewed artists address incisively. Most of them embrace exploratory, open-ended approaches to thinking about intersectional, nonlinear space and time. Importantly, their ideas align well with contemporary scholarship around multiplicity—or “global modernisms,” as it is often called—where such thinkers write into the art historical canon by including local and transnational stories and disrupt the myopic linearity of the Western narrative. Because this area of study is still developing, it strikes me that Obrist was ideally poised to explore this multiplicity through The Athens Dialogues.Disappointingly, the artists’ perspectives are often restricted by Obrist’s Western-centric methods.

Whereas Obrist envisions a past severed from the present, most of the interviewees do not see themselves as temporally dislodged. In their interviews, artists such as Christiana Soulou, Hito Steyerl, and Shuddhabrata Sengupta illustrate that the structures through which we understand history and temporality are by no means fixed. In fact, they are malleable and, in some cases, mythical. Soulou notably challenges Obrist’s invocation of Panofsky with a citation of Roland Barthes in which he refers to the contemporary as “inactual.” Soulou continues by describing a present that is not temporally polarized but an “atmospheric mixture” of periods. Sengupta steps outside of temporality altogether to eloquently question the location of the West as part of a larger argument around the narratives and mythologies of history in general. He also points to mythology as part of history, and speaks about the connections between Greek and Sanskrit traditions. In doing so, he positions linearity as a Western construct and gestures to transnational dialogues.

Such artists as Danai Anesiadou, Isaac Julien, and Adrián Villar Rojas suggest that the selective nature of the Western narrative has significantly affected the way Greece is understood in the broader imagination, specifically by its framing as the “cradle of Western civilization.” Rojas notes that this process began with the archeological excavation of Athens by the US, UK, France, and Germany, in which the funding did not include digs related to Eastern cultural traces. Anesiadou reflects upon the removal of color from the stolen Greek marbles, an act that literally erased signs of antiquity’s multiethnic cultures and polychromatic artistry. Relatedly, Julien questions the perception that Greek antiquity moved exclusively Westward, and describes his filmic exploration of a local Mediterranean history that acknowledges the Southern and Eastern African countries that share the region.

Obrist’s arguments about temporality are incompatible with these artists’ observations. Perhaps, in an attempt to open up space for diverse perspectives on the topic, or thanks to a lack of interest in the continued study of antiquity, Obrist’s reassertion of the decontextualized Panofsky quote quickly begins to read as disengagement with both Panofsky and the artists included in the book. Although Obrist is clear that the book is actually about his own interviewing practice (the book’s first sentence reads, “Everything began when I was seventeen years old with Peter Fischli and David Weiss”), one might ask, to what end? What are the stakes of this project for Obrist? Why are these artists being engaged? And furthermore, why would antiquity be a “toolbox” unless it was the property of the West, dislodged from its context, or a series of representations of something misunderstood? Once I started asking these questions, I realized that this work is a case of transmission pedagogy gone awry. When a curator becomes more engaged with his own practice than with the material conditions of artistic production, the best thing for us to do is to just look elsewhere.

Ari Marcopoulos’ contribution should not go overlooked. His photographic essay threads throughout the book. The fragmentary nature of The Athens Dialogues is visually offset with more than 120 of Marcopoulos’ photographs, rhythmically dispersed. The images are anti-narrative; avoid direct illustration of the texts; and, importantly, capture the quotidian heterogeneity of contemporary Athens. Ruins, museums, laborers, abandoned storefronts, public buses, political graffiti, and portraits of young Athenians are benevolently captured, making an apt inclusion to the book. These photographs remind me of Allan Sekula’s essay “Photography and the Limits of National Identity,” in which he writes about a photographer who stares at a mass grave, realizing she is looking at something that history has not memorialized. She searches for truth, not in the academy but by crouching down to the earth and digging for that which is buried.

Magdalyn Asimakis is a curator and writer based in Toronto. She is a PhD candidate at Queen’s University and co-founder of the curatorial collective and roving project space ma ma.